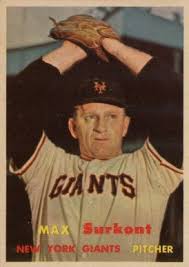

Max Surkont

In 1942 St. Louis Cardinals’ farm director Branch Rickey singled out a particular right-handed hurler among a small army of top-flight pitching prospects: Max Surkont “can become another [Bob] Feller for us,”1 declared the future HOF executive. But by the end of spring training the Cardinals, blessed with the major leagues’ best pitching, assigned Surkont to their International League affiliate in Rochester, New York. Originally signed in 1937 at the tender age of 15, the demotion marked the fifth of nine years Surkont spent in the minors, plus three years in the military, before he got his first crack at the majors. In a professional career spanning 24 seasons, Surkont would not serve on a pennant-winning club for 20 years. Along the way he established a modern record of eight consecutive strikeouts that stood for 17 years until shattered by future HOF righty Tom Seaver in 1970.

In 1942 St. Louis Cardinals’ farm director Branch Rickey singled out a particular right-handed hurler among a small army of top-flight pitching prospects: Max Surkont “can become another [Bob] Feller for us,”1 declared the future HOF executive. But by the end of spring training the Cardinals, blessed with the major leagues’ best pitching, assigned Surkont to their International League affiliate in Rochester, New York. Originally signed in 1937 at the tender age of 15, the demotion marked the fifth of nine years Surkont spent in the minors, plus three years in the military, before he got his first crack at the majors. In a professional career spanning 24 seasons, Surkont would not serve on a pennant-winning club for 20 years. Along the way he established a modern record of eight consecutive strikeouts that stood for 17 years until shattered by future HOF righty Tom Seaver in 1970.

Matthew Constantine (Max) Surkont was born on June 16, 1922, one of at least three children of Bronislaw “Bernard” and Malwina (Bardowska) Surkont in Central Falls, Rhode Island, a small city abutting Pawtucket. Little is known of Max’s parents. Bronislaw was born in 1882 in a small village 50 miles southwest of Warsaw, Poland. He immigrated to the United States around the turn of the century, though it is unclear if he was married before he settled near the Blackstone River in Central Falls. Max became fluent in the English and Polish languages. Later described as a “[w]ide-shouldered . . . six-footer who stripped looks stronger than the strong man in a circus,”2 in 1937 the 15-year-old blonde claiming he was 18 used his physical attributes to gain entry to a Cardinals tryout in Providence, Rhode Island. “I threw only three pitched balls—and [scout Pop Kelchner] gave me a contract,” Surkont later recalled. “I was so surprised I could hardly walk off the field without stumbling.”3 After Kelchner discovered Surkont’s true age, he tracked Max’s father to his job at a cotton mill in Pawtucket where Bronislaw gave his approval to a $50 bonus and $100 a month salary.4 Assigned to the Rochester Red Wings as a batting practice pitcher, Surkont would lose a lot of sleep as the target of the veteran players’ pranks: “One night on a train, Estel Crabtree told me . . . to stay up all night and watch the red lantern at the end of the train . . . to make sure it didn’t go out—so we wouldn’t have any accident. Another time Tony Kaufmann asked me to watch the shoes to make sure the porter didn’t steal them.”5

In 1938, Surkont took the field with the C Portsmouth (Ohio) Red Wings in the Middle Atlantic League. Enamored with his blazing fastball, the club could not abide his erratic control, however. After two appearances he was demoted to the Eastern Shore League. Returned to Portsmouth the next year, Surkont continued to struggle with his control, yielding a league leading 163 walks in 218 innings though still placing among the circuit leaders with 14 wins. Promoted to the Three-I League in 1940, Surkont’s career surged despite 19 wild pitches, he posted a record of 19-5, 2.50. He captured the ERA and strikeout (212) crowns while leading the circuit in winning percentage (.792). Befriended by Cardinals’ veteran ace Lon Warneke the following spring, some speculated that the 19-year-old would make the long jump from Class B to the majors. Instead Surkont was assigned to AA Rochester where he earned a reputation alongside flamethrowers Virgil Trucks and Ed Head as the fastest hurler in the International League. In August 1941, Surkont faced the Jersey City Giants and pitched what is believed to be his only career no-hitter, one of his five league leading shutouts. He finished the season with a record of 10-6, 3.20 in 163 innings.

Inexplicably Surkont was unable to build upon this success, though there is reason to believe that the arm problems that plagued him upon his return from the service may have originally started in 1942. Returned to Rochester just days before Opening Day—an indication the Cardinals were strongly considering retaining the youngster— Surkont put up the league’s worst numbers in runs allowed (130) and losses (18) and was among the circuit leaders in walks (107). Four years passed before he would have an opportunity to bounce back.

On October 26, 1942 ,Surkont entered the US Navy, serving as a gunner’s mate on a tank landing ship in the Pacific during World War II. Three years later petty officer second-class Surkont was transferred to Norfolk, Virginia, ostensibly as a gunner-mate instructor, though his main responsibilities appear to have been pitching for the shipyard’s baseball team.6 He was discharged on January 6, 1946.

Reunited with the Cardinals in the spring, Surkont displayed the promise Rickey and others had seen previously. On March 9, in his first professional appearance in four years, Surkont combined with two others to hold the New York Yankees to one unearned run over eight innings of grapefruit league play. Three days later Cardinal manager Eddie Dyer was further impressed after Surkont surrendered just three hits in five innings against the Cincinnati Reds. On April 15, in a surprise move, the Cardinals traded Surkont and first baseman Ray Sanders to the Boston Braves for infielder Tommy Nelson and $40,000. The move was an apparent attempt to move Surkont after bone chips were discovered in the righty’s elbow. Within two weeks, the Braves discovered Surkont’s ailing arm, and he was returned to St. Louis along with a $15,000 refund. Once the Cardinals’ surgeon determined an operation unnecessary, Surkont was returned to Rochester.

Surkont endured Rochester for the next three years with mixed success, pacing the league in losses (17) in 1946 while placing among the leaders in wins in 1947-48. In the latter year he put together an impressive string of 11 wins in 12 decisions to earn post-season consideration for the circuit’s MVP award. When the Cardinals tried to promote Surkont, the International League blocked them. Citing three prior occasions when a promoted hurler returned to the minors before making a single appearance—a blunder to which farm director Joe Mathes confessed—league president Frank Shaughnessy ruled the pitcher could not be moved up again to the big leagues without exposure to the rule 5 draft. Boston Red Sox minor league director Specs Toporcer closely monitored Surkont’s progress in 1948. Poised to draft the hurler into the Red Sox fold when he was dismissed during the year, Toporcer was quickly hired by the Chicago White Sox. He played a key role in Chicago’s selection of Surkont in the November 10, 1948, draft.

The acquisition elated new White Sox manager Jack Onslow. A former major league catcher and scout for the Braves, Onslow knew Surkont well, having scouted the youngster on Boston sandlots.: “If [Surkont’s] speed and all-around ability don’t make him a big league pitcher,” said Onslow’s equally excited friend Jewel Ens, former Pittsburgh Pirates infielder and manager, “then I’m ready to say I don’t know a ball player,”7 On April 19, 1949—Opening Day—Surkont made his major league debut with one inning of relief against the Tigers in Detroit. Five days later he collected his first decision with a ninth-inning walk-off win against the St. Louis Browns. Excepting two starting assignments—including a heartbreaking May 30 loss an out away from a four-hit, 2-1 win against the Tigers via a Luke Appling error—Surkont worked exclusively from the bullpen. On June 16, he made his first appearance in Yankee Stadium in relief of Billy Pierce. Though Surkont immediately plunked future HOF catcher Yogi Berra and struggled with his control, he succeeded in keeping the Yankee sluggers off balance through nine innings to capture his second career win. “You know—that’s almost every youngster’s ambition,” Surkont said. “[T]o pitch and win there.”8 He collected another win against the Yankees a month later before hitting a terrible slide: 0-2, 11.40 in 10 appearances through August. Attributing the collapse to a tired arm, Surkont chose rest in the offseason, instead of his usual pitching in the Cuban or Venezuelan Leagues.

For all the good it did. The White Sox optioned him to the Pacific Coast League over Onslow’s objections, who would himself become unemployed 30 games into the season. Hurling for the last-place Sacramento Solons, Surkont stood among the league leaders in nearly every pitching category and earned an All Star berth. Adept at the plate, he was frequently used as a pinch-hitter and delivered at least three game-winning hits. On August 18, after attracting interest from the Yankees, Surkont was traded to the Braves for pitcher Glenn Elliott and $15,000.9 Joining a staff of Warren Spahn, Johnny Sain, Vern Bickford, and little else, Surkont’s record of 5-2, 3.23 in nine appearances (six starts) boosted the roster. Noting the seven Braves errors in Surkont’s two defeats, manager Billy Southworth exclaimed, “Surkont shouldn’t have lost a game.”10 Envisioning the righty as the Braves’ long-awaited fourth starter, Boston sportswriter Bob Ajemian enthused about a future pennant for the club, declaring that “Surkont may become one of the winningest righthanders [sic] in the league.”11

Surkont set out to prove him correct. In his first appearance of the 1951 season he held the reigning NL champion Philadelphia Phillies to one hit over 7⅔ innings and knocked in the winning run himself in a 2-1 complete game victory. On April 28 Surkont earned his first career shutout, and three months later he threw his second against his former Cardinal teammates. But his season had begun sputtering as arm problems that initially surfaced in spring training plagued him throughout the year. A proud Rhode Islander, Surkont was joined by fellow-Ocean State natives Phil Paine and Chet Nichols on the Braves staff, “the first time since the 1800s that three from the state played on the same major-league team.”12 But his pride did not dispel the disappointment of Surkont’s 12-16, 3.99 ERA year.

Surkont’s 1952 season proved the mirror opposite of 1951: he started slowly and finished brilliantly. Consistency was elusive. Too often a notable start like the two-hit shutout against the Chicago Cubs on June 15 was offset by a five-inning, seven-run beating from the Cardinals a month later. On August 1 Surkont carried a four-hit shutout into the ninth against the Cincinnati Reds before two wild pitches (the latter later changed to a passed ball) led to a loss. But then he won four straight and went 6-3, with a 2.85 ERA and two shutouts in his final 10 starts. One shutout came on August 8 against the New York Giants, following a pre-game “Surkont Night” celebration. A Rhode Island delegation had honored him with gifts of a television, home air conditioner, and other fine items. Giant manager Leo Durocher put a damper on the celebration, however, accusing Surkont of throwing a spitter. If this were the case—and later Surkont readily admitted throwing the illegal pitch—it proved to be one of the few occasions in which the pitch proved effective. “I stopped using it,” Surkont admitted years later. “[T]oo many of them were sailing out of the park. If everybody threw a spitter as lousy as I did, the hitters would be yelling for it to be legalized.”13

The Braves relocated to Milwaukee before the start of the 1953 season. And in the Milwaukee Braves first game ever on Opening Day in Cincinnati, Surkont retired the last 14 Reds in order for a 2-0 whitewash, becoming the last pitcher to hurl an Opening Day shutout against the Reds until 2014. (The club appears to have held their ace, future HOF lefty Spahn, for the next day’s home opener). Six weeks later Surkont faced the Reds again and set a Braves’ record 13 strikeouts, including a modern major-league mark of eight consecutive. The ball was donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame while the record, later tied by Johnny Podres, Don Wilson and Jim Maloney, stood for 17 years. On June 16—his 31st birthday—Surkont’s nine wins stood among the major league leaders. Braves’ fans showered him with gifts, including a $1,000 bond and a year’s supply of sausage from Milwaukee’s large Polish community. A month later Surkont held the Phillies to four hits over 10 innings, his last career shutout. Crediting Surkont’s offseason conditioning for the brilliant start, Braves manager Charlie Grimm said, “He worked hard this spring . . . He battles you out there. He has a good sinker, curve, control—and heart.”14

Nonetheless Surkont was abruptly removed from the rotation following his August 14 start against the Chicago Cubs. The Braves cited a budding youth movement, but Surkont felt it was the club’s deliberate attempt to avoid paying him a promised bonus of $500 for every win over 12; he finished with a record of 11-5, 4.18 in 170 innings. On December 26, Surkont and a large package of players and cash went to the Pittsburgh Pirates for prized infielder Danny O’Connell. “I was real pleased with [the acquisition of] Surkont,” said Pirates’ manager Fred Haney. “He [will] win some games.”15

In 1954 Surkont roomed with infielder Eddie Pellagrini and southpaw Joe Page at the Pirates new spring training facility in Fort Pierce, Florida, during Page’s short-lived comeback attempt. When Haney learned about Page’s loud snoring, he could not resist needling his roommates: “Page has an unusual quirk in that he’s a sleepwalker who likes to imagine he’s a barber,” he told them. “He takes a straight razor and will frequently shave a sleeping roomie without bothering to lather him up. So you boys better hope that Page keeps snoring.”16

In comparison to the real challenges Surkont faced, the chimera of a potentially lethal roommate might have seemed minor. Physical ailments began creeping up on the 32-year-old veteran. . Weight issues, a career-long problem, also hindered him. “I don’t feel right physically and I get tired late in the game,” Surkont said. “I run out of gas.” But as a senior statesman and the player-representative on the young club Surkont always maintained a sense of humor. He once quipped that the Pirates’ flood of high-priced bonus babies were more likely to pick up a copy of The Wall Street Journal before ever perusing The Sporting News.17

In two full seasons with the Pirates Surkont suffered through a 16-32, 4.92 record including a single-season career-high 25 homers yielded in 1954 and an eight-game losing streak to finish the next season. Despite these challenges the club received numerous trade offers for Surkont, including two aggressive pursuits from the Cardinals.18 After making just three starts over the last nine weeks of the 1955 season Surkont bid farewell to his teammates with little expectation of seeing them again.

His prediction was off by only one appearance. On May 6, 1956, after sitting on the far end of the bench through the first 17 games, Surkont pitched two inning of relief in Chicago. The same day he was traded to the Cardinals for pitcher Luis Arroyo. Joining a staff that included 41-year-old Ellis Kinder and 39-year-olds Murry Dickson and Jim Konstanty—the Red Birds’ GM Frank Lane had claimed he would “sign Methuselah if he can win for us,”19—Surkont felt like a youngster. Promised a role as a spot starter, he struggled in five relief appearances and was sold to the San Francisco Seals in the PCL (the Red Sox’ AAA affiliate) on June 4 for an estimated $15,000. Bitterly resenting the demotion, Surkont threatened to retire. PCL umpire Mel Steiner would soon be glad he didn’t.

In San Francisco on June 24 fans erupted into a riot after Steiner’s second controversial call against the Seals in the game, a call at the plate that resulted in a game-ending loss for the club. Before police arrived “fans swarmed onto the field [and] attacked Steiner.” Surkont and his teammate Jerry Casale helped hold them off until Steiner could reach safety.20 Fortunately Surkont offered more substantial contributions to the Seals. On July 11 he shutout the Sacramento Solons and, despite a middling 4-6 record, finished his short campaign with a league best 2.38 ERA (100-plus innings). A month later the Giants, besieged by injuries to pitcher Al Worthington and others, acquired Surkont for $20,000 and two players to be sent the next spring.21 On August 23, in his first start as a Giant, Surkont carried a one-hit shutout into the seventh against the Cubs before second baseman Gene Baker connected for a grand slam; Surkont still came away with the win. Excepting a miserable start two weeks later against the Brooklyn Dodgers, Surkont finished with a respectable 2-2, 4.78 in eight appearances. During the offseason he was projected as a Giants’ starter in 1957 despite his age.

But a rotation spot eluded Surkont after a difficult spring that included a first inning five-run pounding by the Cubs in Mesa, Arizona. Excluding an April 24, 1957, appearance against the Dodgers in which he struck out six of nine batters, Surkont struggled from the bullpen still plagued by a back injury sustained in spring training. On May 1, he ingloriously lost an extra-inning game against the Braves after facing just two batters: Danny O’Connell who tripled and Hank Aaron who singled him home. It was Surkont’s final appearance in the majors. Days later he was sold to the Minneapolis Millers in the American Association.

From May 1957 through early 1963 Surkont toiled successfully amongst four franchises without receiving a hint of consideration for another major league call. In 1957 he placed among the league leaders with 15 wins and 115 strikeouts. The next year, pitching for the Seattle Rainiers, he twirled a near no-hitter against Sacramento. In 1959, while with the Buffalo Bisons in the International League, for the first time in the 37-year-old’s long career, he enjoyed a pennant-winning season. In 1961 he added a knuckleball to his repertoire and, while working exclusively in relief, earned consideration for the circuit’s Most Valuable Pitcher award. Two years later he served as the Bisons pitching coach—making two unremarkable appearances—before retiring to his home in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, to his family of six.

In 1948 Surkont had married New York native Jeanne Hall in Dade County, Florida, and together they had four children. Surkont had worked for a variety of employers during his off-seasons, including a defense manufacturer in Attleboro, Massachusetts. Sources indicate he also did some barnstorming. He had long expressed a desire to become a professional umpire to stay in baseball. Instead Surkont opened a neighborhood bar called Max Surkont’s Café. “It was the type of place a workman would go to after leaving the factory and have a beer,” remembered SABR member Len Levin. Surkont later invested as a partner in a small Pawtucket shopping center.

Throughout his career Surkont forged strong relationships wherever he went, especially with the vast Polish immigrant communities in Milwaukee, Buffalo and at home. He lent time to many charitable endeavors including a March of Dimes fundraiser in Attleboro in 1953 and visiting the Veterans Hospital outside of Pittsburgh the next year. On June 2, 1954, a year removed from Milwaukee, the city honored him with a lifetime membership in the St. Joseph’s Orphanage Athletic Association.

Surkont earned recognition for his athletic prowess as well. In February 1951, Pawtucket hosted a dinner honoring him. Two years later he was awarded the Outstanding Rhode Island Athlete of 1953 at a Providence sportswriters’ banquet. Years later, on April 15, 1965, a noticeably heavier Surkont travelled to Wisconsin to share in the 12th anniversary festivities as one of the original Milwaukee Braves. But perhaps the greatest honor came in 1986 when he was among the inaugural induction class of the Pawtucket Hall of Fame.

Two years earlier Surkont closed the café and moved to Florida with his wife. On October 8, 1986, four months after his 64th birthday, he died in Largo, Florida. He was buried in Notre Dame Cemetery in Pawtucket.

Surkont spent four decades in professional baseball, but only nine years in the major leagues. He compiled a record of 61-76, 4.38 ERA, with 571 strikeouts and seven shutouts in 1,194⅓ innings (236 appearances, 149 starts).

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative.

Sources

Notes

1 “Cards Shaping Up Bully to Billy, His Deck Full of Aces,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1942: 1

2 “Surkont Sizzles as Winner and Whiff King for Sad Sacs,” ibid., June 7, 1950: 34.

3 “Braves’ Max Earned First Job With 3 Pitches,” ibid., May 2, 1951: 3.

4 Another source suggests that a judge had to approve the deal for the under-aged Surkont. A amusingly related but unconfirmed story surrounding the signing is offered by SABR member Len Levin, who was a friend of Surkont’s: It was said in the Pawtucket-Central Falls area that after signing Max, the Cardinals took him out to lunch and when asked what he wanted he answered, as any young teenager might, frankfurters and beans. I never asked Max about it, because by the time I heard it, he had already moved to Florida.

5 “Surkont Sizzles as Winner and Whiff King for Sad Sacs,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1950: 34.

6 Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball in Wartime,” July 11, 2008. Accessed April 4, 2016, http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/surkont_max.htm

7 “Old Friendship Pays Off for Freshman Jack Onslow,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1949: 10.

8 “Max Pours Out Strikeouts for Record in Rain,” ibid., June 3, 1953: 11.

9 One report suggests that another unidentified player was sent to the White Sox. The Braves’ interest in Surkont resulted largely from Onslow’s appeals after he was released by the White Sox. In turn, Surkont’s appeals resulted in the Braves’ acquisition of his fellow PCL pitching star Jim Wilson.

10 “Braves Get Off to Early Start in Hunt for Fourth Hill Starter,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1950: 4.

11 “Braves’ Three Little Shovels Cut to Two; Rudo Sells His Stock,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1951: 19.

12 Nelson ‘Chip’ Greene, “Phil Paine,” March 10, 2011. Accessed April 10, 2016, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/48729b39.

13 “Why Surkont Stopped Using Spitter,” The Sporting News, September 19, 1956: 12.

14 “Hands Too Small? Grimm Scoffs at Rajah’s Size-Up of Mathews as Infielder,” ibid., May 6, 1953: 11.

15 “Haney Sees Only Four Open Spots on Buc Hill Staff,” ibid., March 17, 1954: 12.

16 “From the Ruhl Book,” ibid., May 5: 14.

17 “Surkont, Down 30 Pounds, Tires During Late Innings, ibid., May 12: 20. In 1955 Surkont was the only Pirates player with more than five years major league experience.

18 In June 1954 Pirates’ GM Branch Rickey appears to have overplayed his hand by offering Surkont to the Cardinals for Dick Schofield, Bill Virdon, a third unidentified minor leaguer, and $100,000.

19 “Lane Sees Cards Flag With New Hurlers,” The Sporting News, May 23, 1956: 4.

20 “’Frisco Fans Toss Cushions, Fists Over Steiner Decisions,” ibid., July 4: 28.

21 In 1957 pitcher Windy McCall was sent to the Seals. The second player reportedly sent was outfielder Bill Taylor though no evidence suggests he ever played in San Francisco.

Full Name

Matthew Constantine Surkont

Born

June 16, 1922 at Central Falls, RI (USA)

Died

October 8, 1986 at Largo, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.