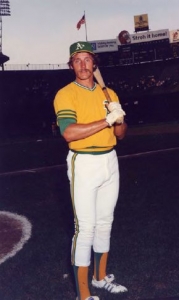

Champ Summers

Baseball history is filled with all variety of wonderful-sounding names. But has there ever been a more perfect name for a baseball player than Champ Summers? “With a name like that, you gotta be halfway decent anyway,” Champ would say years later. “If my name had been George, nobody would have noticed me, but Champ?” Growing up, Summers had to constantly prove that he was as great and as tough as his name implied. “A kid would come up to me and say, ‘What’s your name?’ I’d say, ‘Champ.’ He’d say, ‘Champ?’ And away we’d go. I got into more than a few fights because of my name.” As evidence of his pugilistic past, Champ’s left cheek was adorned with a large scar. “It happened a long time ago, when I used to roam the streets.”1

Baseball history is filled with all variety of wonderful-sounding names. But has there ever been a more perfect name for a baseball player than Champ Summers? “With a name like that, you gotta be halfway decent anyway,” Champ would say years later. “If my name had been George, nobody would have noticed me, but Champ?” Growing up, Summers had to constantly prove that he was as great and as tough as his name implied. “A kid would come up to me and say, ‘What’s your name?’ I’d say, ‘Champ.’ He’d say, ‘Champ?’ And away we’d go. I got into more than a few fights because of my name.” As evidence of his pugilistic past, Champ’s left cheek was adorned with a large scar. “It happened a long time ago, when I used to roam the streets.”1

It was his father, himself a boxing champion from his days in the US Navy, who gave Champ his nickname. “When I was born I was so ugly I looked like I’d been beaten around in the ring. They called me ‘Champ.’ ” There was also a slightly different version of the tale. “Dad took one look at me when I was born and said, ‘He looks like he just went ten rounds with Joe Louis.’ It’s a sad story, but true.” His father always made it clear that he would be known as “Champ.”2

Summers, who spent part of the 1974 season as a bench player with the Oakland Athletics, was born John Junior Summers, II on June 15, 1946, in Bremerton, Washington, the home of the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard.3 A copy of Champ’s birth certificate reveals his father’s name as John Junior Summers, originally from Sparta, Illinois. The elder Summers listed his occupation as “self-employed photographer.” His mother, Bette Irene Mace, claimed to be a housewife, born in Big Lake, Washington. A self-described hustler and scrapper, Champ spent a lot of his formative years hanging around pool halls. Despite having plenty of opportunities to get into trouble, he credited his strong home life with keeping him on the straight and narrow. When he turned 16, however, Champ decided to get a tattoo of a Playboy Bunny etched on his right shoulder. He would live to regret the frivolous decision. “I hate that thing,” he said in later years. “Now, it follows me wherever I go. It cost me $5 to have it put on, but it would cost me $5,000 to get rid of it.”4

Eventually, the Summers family moved to Illinois. Champ graduated from Madison Senior High in 1965. He was a natural athlete, lettering in basketball, football, tennis, track, and cross-country. He was also a swimmer and a diver. Up to this point in his life, however, he had not yet played baseball seriously, claiming that while the opportunities were there, he simply had no interest in the game.

Upon graduating from high school, Champ enrolled at Nicholls State College in Louisiana. He played basketball, but after what he called a misunderstanding with the coach, he dropped out after a year and a half. The “misunderstanding” actually involved Summers punching out a teammate. “I went to Vietnam for that,” Summers said later. “They kicked me off the team. So I dropped out of school, and the Army grabbed me. It was the best thing that ever happened to me. Vietnam was tough. It made me a different person. I saw them put people in bags and decided they were going to know I had been there before they put me in one. I became more aggressive, more assertive. I came back home and got an education, something I hadn’t wanted before. If I hadn’t punched that guy and gotten kicked out of school, I wouldn’t have gone to war, and I might have settled for the kind of life my father had led.” Summers said that his father had “worked on the railroad all his life. I had worked with him. I didn’t want to do that.”5

Summers spent 11½ months in Vietnam. The first six were spent as a paratrooper. The rest of his service time was on the beach, as a lifeguard. But while jumping out of planes, Champ witnessed firsthand the horrors of war, forcing him to grow up quickly. “I don’t like to talk about it. Looking back now, it was probably a good thing for me, … It made me feel how insignificant I was.”6 He narrowly escaped with his life in one instance. While behind the wheel of a truck, he drove over a land mine. Fortunately, sandbags in the vehicle absorbed much of the shock. Summers suffered a concussion and a broken nose.

After the Army, Summers attended Southern Illinois University Edwardsville in 1970. He played on the basketball team for two seasons, averaging 18.8 points per game, including one game in which he scored 53. He was a talented enough player to earn a tryout with the Memphis Tams of the American Basketball Association. At some point, he was also offered a tryout with the Dallas Cowboys of the NFL. Champ had never played college football, however, and never followed up on the offer.

While at SIUE, Summers met his future wife, Barbara, a fellow student. After dating for about a year, they married in 1971.

During Champ’s senior year he first began to play organized baseball. “I was playing a little slow-pitch softball and one day one of my friends said I should go out for the baseball team. Sounded like a good idea. … Why not?” At the time, he assumed that the skills needed for playing slow-pitch would translate over to baseball. “You run around in the outfield and catch the ball just the same, don’t you?”7 Summers approached the baseball coach, Roy Lee, and told him he wanted to try out for the team. Naturally, Lee expressed skepticism when Summers told him he hadn’t played baseball of any kind since he was 13, and not in any organized fashion. Lee gave in against his better judgment, and Summers got in the cage and swung the bat. Coach Lee supposedly asked his newfound slugger where the hell he had been. Summers hit a pinch-hit homer his first time at bat in a game.

Champ’s greatest thrill in college was ranking in the top ten in the NCAA in home runs (7) and RBIs in 1971. He was also voted SIUE’s Athlete of the Year in 1971, hitting .340. Years later, former SIUE baseball coach Gary “Bo” Collins could still remember the day Summers came for his tryout, “riding down to the field on a Harley without a shirt on … his hat on backwards.”8

Summers was not drafted by any major-league team upon graduation. But his baseball odyssey was not coming to a close. It was only beginning.

While playing at SIUE, Summers had been spotted by George Bradley, a scout for the Oakland A’s. He liked what he saw in Champ, despite his relatively advanced age. A’s owner Charlie Finley wasn’t too excited about signing a player who was almost 25 and whose only baseball experience was 35 games in college. Bradley was a good salesman, however, and talked Finley into giving Summers a contract.

At first Summers himself wasn’t sure he wanted to sign with Oakland, but his wife, Barbara, urged him to at least give it a try. If nothing else, he could say years later that he had played professional ball. On June 12, 1971, Summers signed for a reported $500 per month, no signing bonus, and reported to Class A Coos Bay-North Bend in the Northwest League. In 65 games he hit .252, with three home runs and 34 RBIs. Champ hated the 15-hour bus rides, the lousy truck-stop food, and the dirty hotel rooms, but again, it was Barbara who encouraged him to give it at least one more year, knowing that it was something that he really wanted.

Summers played the following year at Burlington (Iowa) in the Class A Midwest League, finishing with 10 homers, 54 RBIs, and a .308 average in 97 games. That earned him a promotion to Triple-A Tucson for 1973, where he hit .333 in 94 games, but with only eight homers. He began the next season at Tucson again, but soon Oakland decided he had earned a promotion. Champ Summers finally appeared for the first time in a major-league contest on May 4, 1974, at the ripe age of 27. Against the Indians in Oakland, he was inserted as a defensive replacement in the top of the ninth, for none other than Reggie Jackson. In the bottom of the inning he got his first major-league at-bat, against Gaylord Perry, hitting into a line-drive double play to the first baseman. Thus, in his first game as a big leaguer, he replaced a Hall of Famer, and faced a Hall of Famer. His first hit came at the Oakland Coliseum on May 14, 1974. It was a pinch-hitting appearance in the ninth inning against the Kansas City Royals’ Doug Bird, a groundball single to center.

By early June, Summers was back at Tucson. In 20 games at Oakland, he had only three hits in 24 at-bats, for a .125 average, with no homers and three RBIs. At Tucson he hit .263 with 10 homers and 59 RBIs in 94 games. That October, Oakland won its third straight World Series. Summers, though not on the team after June 10, received a Series share of $100 from the A’s. (According to Champ, the check was actually $93 after taxes.)

That first season in Oakland, Summers lived with Reggie Jackson. Reggie, no stranger to self-promotion, taught Champ a thing or two. “I was autographing baseballs one day,” he recalled, “and Reggie wanted to know why I was signing them John Summers. He asked if I had a nickname. I told him I had one, but I was afraid of what the other players would think if I used it. Reggie said, ‘This is show business. If there were two Summers with the same ability, one named John, and the other name Champ, which do you think the fans would remember?’”9

In 1975 Summers started the season at Tucson once again. On April 29, after 17 games, he was informed that he could pack his bags for Chicago. Wrigley Field would be his new home. He had been traded to the Cubs.

Summers spent the rest of 1975 in the Windy City, mostly as a reserve outfielder and pinch-hitter. He hit .231 with one home run and 16 RBIs in 76 games. That home run, however, on August 23 at Wrigley Field, was his first in the majors, and a pinch-hit grand slam at that.

After the season Summers played for Culiacán in the Mexican Pacific League. He played every day, and made the All-Star team. Back in a Cubs uniform for 1976, he hit only .206, with three home runs in 83 games. The Cubs had labeled Champ as nothing more than a pinch-hitter. Perhaps the team felt that he was unable to hit left-handers, was too much of a defensive liability, or that he was simply too old. On February 16, 1977, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds. He would become the team’s primary pinch-hitter from the left side. The Big Red Machine, managed by Sparky Anderson, was coming off their second consecutive World Series championship. Summers knew that, barring injury, there was just no way he was going to break into such a great lineup. He understood his role on the team. He struggled for much of the year, finishing with a .171 average in 59 games, with three homers and six RBIs. By the end, he said, he was pressing so much, and so worried that the Reds were going to demote him, that he could hardly function. His highlight was an inside-the-park home run in June at Riverfront Stadium.10 That year the Reds were bridesmaids to the Dodgers. Still, Summers earned a second-place booty of $2,011.35.

The following summer would prove to be a pivotal one in Champ’s career, but it wouldn’t be spent in Cincinnati. Just before Opening Day, the Reds optioned him to Triple-A Indianapolis. He had a monster season for the Indians, hitting 34 homers with 124 RBIs, while batting .368. “This season here,” Summers said when it was all finished, “I’ll never forget. It has probably turned my whole life around.”11 He won the American Association MVP award, as well as The Sporting News Minor League Player of the Year award.

Called up to the Reds in September, Summers wound up hitting .257 in 13 games with one home run, a titanic clout into the top-tiered red-level seats at Riverfront Stadium. After the season he joined the Reds on their tour of Japan, hitting .370 with five homers.

Champ was back on the Reds for 1979, but again it was tough for him to crack an outfield of Ken Griffey, George Foster, and César Gerónimo. He never got untracked, and after hitting only .200 with one homer in 27 games, he was dealt on May 25 to the Detroit Tigers. Tigers manager Les Moss had high hopes for his new acquisition. Moss, however, wouldn’t see Champ very long in Detroit. On June 11, the skipper was unceremoniously let go. Taking his place was Champ’s former manager at Cincinnati, Sparky Anderson, who had been fired by the Reds in November of 1978 after their disappointing second-place finish. The Tigers felt they simply couldn’t pass up the opportunity to hire one of the most successful managers in the game. Platooning in left and right fields, Summers played 90 games for Detroit. His left-handed swing was tailor-made for Tiger Stadium’s short right-field porch. He hit a career-high .313, with a .414 on-base percentage, while slugging .614. He banged out 20 home runs with 51 RBIs. He struck out only 33 times. Summers admitted at season’s end that he hadn’t been a very happy person until day one when he got to Detroit. He felt ready to shed his reputation as a platoon player. Sparky, however, saw Champ as a very good hitter, but a part-time one.

Summers was very popular in Detroit, especially with the fans in the right-field bleachers, which came to be known as Champ’s Camp. He gained some national recognition in 1979 after a group of fans held up a banner during a Game of the Week telecast when the Tigers played in Milwaukee. The banner read “Champ Summers Fan Club, Berkeley, Calif.” The fan club, which numbered about 30 people, organized a tour to follow their hero from city to city. The recognition Champ received in Detroit did not go unappreciated. “I love it here,” he said. “I love the fans. Even when I do badly, they’re on my side. Hey, I could be pumping gas today. I know how lucky I am to be here.”12

The 1980 season saw Summers play primarily as the designated hitter against right-handed pitching, while making spot appearances in the outfield and at first base. Appearing in 120 games, he hit .297 with 17 homers and 60 RBIs. His slugging percentage was .504.

By 1981 Champ’s playing time was being significantly reduced. That season the Tigers were in the middle of a race, narrowly losing out to Milwaukee for the second-half division title. (Because of the players’ strike, the leagues played a split season.) It was a frustrating season for Summers, as he hit a mere three home runs with 21 RBIs in 64 games, while averaging .255.

On March 4, 1982, Champ was traded from the Tigers to the San Francisco Giants for third baseman Enos Cabell and cash. “(The Giants) must want me,” he commented. “It was pretty obvious there was no place for me in Detroit.” Giants manager Frank Robinson welcomed the trade: “It’s good to have a guy like that on the bench because you know he has the capability of hitting it out of the park with one swing.” In 70 games for San Francisco, Summers hit .248 with four homers and 19 RBIs. He particularly excelled as a pinch-hitter, with 10 hits in 31 at-bats, including two home runs and 11 RBIs. Off the field, it was a year of change for Champ, as he and Barbara went through a divorce.

The next season was a disastrous one. After being diagnosed with degenerative arthritis in his left shoulder, he went under the knife, effectively ending his year on June 26. He did manage to return to get four at-bats as a pinch-hitter in September, but went hitless. Playing in only 29 games all season, Summers hit a dismal .136, with no homers and only three RBIs. In December the Giants sent him to the San Diego Padres for utilityman Joe Pittman and a player to be named later (career minor leaguer Tommy Francis).

The summer of 1984 was one of highs and lows for Champ. Reduced to strictly pinch-hitting duty, and now in his late 30s, he knew he was reaching the end of the line as a player. On August 12 he found himself involved in one of the most violent and ignominious days in baseball history. In a game between the Padres and the Atlanta Braves, several bench-clearing brawls broke out. In one, Champ made a mad dash on his own straight for the Braves bench, in order to get a piece of pitcher Pascual Peréz, who had plunked Alan Wiggins earlier in the game. He was confronted at the dugout by a hulking Bob Horner (on the DL with a broken wrist at the time), who proceeded to throw Champ to the ground, assisted by two Atlanta fans who had jumped out of the stands. Several Braves players quickly swarmed onto the pile as Champ lay in the dirt. He also got a cup of beer thrown on him by one rowdy customer. Nineteen players and coaches were ejected, and five fans arrested.

The Padres finished at 92-70 to gain their first-ever division title. As for Champ, he saw action in only 47 games all year, and struggled to hit .185 with 12 RBIs. His only home run of the year, and the final one of his career and a grand slam, came on April 10 at San Diego’s Jack Murphy Stadium. (Interestingly, Champ’s first big-league homer, as well as his last, was a pinch-hit grand slam.)

Summers got only two pinch-hit at-bats in the National League Championship Series, without getting a safety. In the World Series, San Diego squared off against his former team, the Detroit Tigers, winners of 104 games that year. The Tigers ran over the Padres in five games. Summers had been looking forward to seeing some playing time against his old club, but Dick Williams chose to use Kurt Bevacqua as the DH against right-handed pitchers, even though Bevacqua hit from the right side.

After the first two games in San Diego, the Series moved to Tiger Stadium. Champ got a standing ovation from the packed house during the pregame introductions in Game Three. His only appearance in the Series, however, was as a pinch-hitter in Game Four. Facing off against former mate Jack Morris in the eighth inning, he struck out swinging. It was his final at-bat in a big-league uniform. But he received a National League Championship ring for 1984, along with a Series share of $130,000.

Summers wasn’t offered a contract by any club after the season. Now 38 and out of baseball, he tried his hand as a salesman for a Mercedes dealership in Southern California, but didn’t particularly like it. In December of that year, he met his future wife, Joy. They married exactly one year later, and settled down in La Jolla, where Champ enjoyed playing golf year round.

Still, Summers had the itch to get back into baseball. He grabbed the opportunity to be the hitting instructor for the Columbus Clippers, the Yankees’ Triple-A affiliate, who were managed by Bucky Dent. In September of 1989, Yankees owner George Steinbrenner fired skipper Dallas Green, promoting Dent to the managerial post in the Bronx. Champ, too, was called up to the big club, as a hitting coach.

On June 18, 1990, Dent was fired, along with several of his staff, Champ included. The Yankee coaching job would be his last gig in the major leagues.

In 2001 Summers signed on to manage the Gateway Grizzlies, who played in Sauget, Illinois, in the independent Frontier League. The Grizzlies finished with a record of 37-44. After the last out was made that summer, Champ hung up his baseball uniform for the last time. He and Joy retired to Ocala, Florida. Champ was diagnosed with kidney cancer in May of 2010. He fought the disease for nearly 2½ years, before dying on October 11, 2012.

“He loved playing in Detroit the most,” Joy remembered. “He loved and adored Sparky. He loved the fans.”

Sources

American Spectator

Belleville (Illinois) New-Democrat

Cincinnati Enquirer

Crain’s Detroit Business

Detroit Free Press

Enid (Oklahoma) News and Eagle

Portsmouth (Ohio) Daily Times

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

San Francisco Examiner

San Francisco Examiner

The Sporting News

Baseball-reference.com

BND.com

In addition to the above sources, the author would especially like to thank Joy Summers for her wonderful storytelling during a telephone interview in January 2013.

Notes

1 Jim Hawkins, “Boy of 31 Summers Warms Up as New Tiger,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1979, 21.

2 Norm Sanders, “Former Metro-East Standout and Major League Outfielder Champ Summers Dies,” BND.com, bnd.com/2012/10/11/2357039/former-metro-east-standout-and.html, accessed August 1, 2013.

3 During World War II, the city’s population topped out at around 80,000. The war effort was at its peak, and workers flocked to the area to take advantage of the availability of shipbuilding jobs. Bremertons history featured a few notable residents. Jazz legend Quincy Joness family moved to the city when he was 10. It is the birthplace of Bill Gates Sr., the father of Microsoft founder Bill Gates. The latters grandfather ran a furniture store along with an ice-cream parlor in the downtown area. Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard attended Union High School and began his writing career while living in Bremerton.

4 Jim Hawkins, “Boy of 31 Summers.”

5 Phil Collier, “Tag For Summers: Man of Many Talents,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1984, 42.

6 Greg Heberlein and Rick Hummel, “Are These Guys Just Average?”, The Sporting News, May 31, 1980, 3.

7 Mike Myers, “Summers a Champ as Minors Best,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1978, 30.

8 Aaron Goldstein, “Champ Summers, R.I.P.,” The American Spectator, spectator.org/blog/2012/10/12/champ-summers-rip, accessed August 1, 2013.

9 Phil Collier, “Tag For Summers.”

10 After nearly collapsing at the plate, he later admitted that, during his mad dash around the bases, he had nearly choked after swallowing his entire wad of tobacco, and was almost unable to make it to home.

11 Mike Myers, “Indy’s Summers and DeFreites Offer Baseball’s Top One-Two Power Punch,” The Sporting News, September 2, 1978, 45.

12 Tom Gage, “Champ Knockout in Detroit,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1980, 10.

Full Name

John Junior Summers

Born

June 15, 1946 at Bremerton, WA (USA)

Died

October 11, 2012 at Ocala, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.