Sandy Amorós

On October 4, 1955, outfielder Edmundo Amorós helped “Next Year” arrive at last for the Brooklyn Dodgers. His racing catch off Yogi Berra near the left-field line at Yankee Stadium saved the Bums’ 2-0 lead in Game Seven of the World Series. Johnny Podres held on for the remaining three innings to bring Brooklyn its only title. The grab by Amorós still stands as one of the greatest in Series history, and it was the defining moment of the Cuban’s career.

On October 4, 1955, outfielder Edmundo Amorós helped “Next Year” arrive at last for the Brooklyn Dodgers. His racing catch off Yogi Berra near the left-field line at Yankee Stadium saved the Bums’ 2-0 lead in Game Seven of the World Series. Johnny Podres held on for the remaining three innings to bring Brooklyn its only title. The grab by Amorós still stands as one of the greatest in Series history, and it was the defining moment of the Cuban’s career.

Sandy — so called for a supposed resemblance to champion boxer Sandy Saddler1 — was elected to the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame in 1978. He also showed great promise in the Negro Leagues, the Dominican Republic, and Triple-A. In the majors, however, he remained a role player, spending just three full summers there along with fractions of four others. In author Peter Golenbock’s view, a language barrier hindered his career.

“Amorós had been one of the greatest players ever to come out of pre-Castro Cuba. If he had spoken English, he certainly would have played more, because in Cuba he was a .300 hitter in a fast league, was fleet in the field, was excellent at stealing bases, and was a good bunter. But he didn’t learn the language, and it was a handicap that kept him from becoming a star. A manager just doesn’t trust employing a player when he isn’t sure whether the guy understands him or not.”2

After his days as a pro ended in Mexico in 1962, Amorós then fell on hard times, running afoul of Fidel Castro. Poverty and ill health marked the last 30 years of his life.

Edmundo Amorós was born on January 30, 1930, in the Pueblo Nuevo district of Matanzas, 50 miles east of Havana.3 This city is known for Afro-Cuban culture. Many people from the area are called “Congos” — which, as author Roberto González Echevarría notes, is “a common (if tasteless) way of referring to someone who is very black. Cuban blacks themselves apply it to each other. . . . Congos are reputed to be short but tough.”4 Amorós, one of many Afro-Cuban ballplayers from Matanzas, was such a man. At 5-feet-7 1/2 and 170 pounds, he had surprising home-run power. The scout who signed him for the Dodgers, Al Campanis, called him “Miracle Wrists.”5

Edmundo was the youngest of six children born to Guillermo Amorós and Carida Isasi. Guillermo, who labored in sugar cane fields, died when his little boy was just 3. Carida supported her family by working in a textile mill. Edmundo attended school for eight years but began working in the mill too at the age of 14.6

The small but speedy youth had played baseball from an early age; he was already talented enough to hold his own with older players in Matanzas. In 1947, when he was 17, the young black man also drew inspiration from his pioneering future teammate. The Dodgers held spring training in Havana that year, and Amorós later remarked, “When I see Jackie Robinson play in my country, I say if he can do it, I can do it too.”7

In the baseball structure of Cuba before Castro, the cutoff point for the Juveniles division was age 20. In 1949, aged 19, Amorós won the national batting title at this level.8 This is significant because even well into his big-league career, newspapers and Topps baseball cards indicated that he was born in 1932. Yet by 1951, Edmundo had turned pro at home. Clearly the prospect shaved a couple of years off his age for U.S. purposes.9

In early 1950, the young outfielder gained international exposure. From February 25 through March 12, the sixth Central American and Caribbean Games took place in Guatemala City. Cuba won all seven of its games in the eight-team baseball tournament — led by Amorós, who hit .370 with six homers and 14 RBIs. Author Peter Bjarkman described Amorós and pitcher Justiniano Garay as “two initially token blacks carried on Cuba’s roster as racial integration slowly and quietly arrived within Cuban amateur baseball circles.”10

Cuba’s Amateur League, a bastion of white-only private social clubs, actually remained segregated until 1959. There was a strange and surprising Catch-22 at work. Black players could play in the main Cuban professional league but needed places to develop. Yet while two new integrated amateur leagues sprang up in the 1940s, many Afro-Cubans were forced to turn either to semipro ball or the sugar-mill circuit — and thus became ineligible for amateur international competition. Amorós and Garay remained eligible in 1950, though. Joining them was Ángel Scull, another black outfielder from Matanzas, who played nine seasons at Triple-A but never made the majors.

Edmundo then went on to join the New York Cubans, run by Cuban impresario Alex Pómpez, in the Negro American League. Playing first base in addition to the outfield, he hit .338 (an isolated and probably incomplete statistic), with at least one notable homer at the Polo Grounds. Pitcher Sam Williams had promised to knock Amorós down before the game, and sailed a fastball dangerously close to the batter’s head. Sandy then held up his end of the pregame exchange by belting one into the second deck.11

That winter, 24 Cuban sportswriters unanimously voted Amorós Rookie of the Year in the Cuban League. (The records show he played in 41 games but with just 42 at-bats, which is also likely incomplete.) He helped the Havana Rojos (Reds) to their first of three straight Cuban championships under manager Mike González. Down in Caracas, Venezuela, Amorós then went 5-for-15 in the third Caribbean Series, won by Puerto Rico.

The New York Cubans ceased to exist after the 1950 season. During the summer of 1951, Amorós played in the Dominican Republic, where pro baseball had resumed that year (the league would not switch to the winter until 1955). With the Estrellas Orientales club in San Pedro de Macorís, Edmundo went 31 for 79 (.392), scoring 20 runs and driving in 19.12

In the winter of 1951-52, Amorós posted .333-3-27 numbers for Havana and was named a league All-Star. He also attracted the attention of Brooklyn Dodgers coach Billy Herman, who was managing the Cienfuegos team. Herman in turn tipped off Al Campanis, who signed the outfielder for a $1,000 bonus.13 After the Cuban season ended, the Reds went on to the fourth Caribbean Series, played in Panama City. Cuba finished 5-0 with one tie, and Edmundo led all hitters by going 9-for-20 (.450). One of those hits drove in pitcher Tommy Fine with the only run in Fine’s no-hitter on February 21 — a unique achievement in Series history.

That spring, Amorós made his minor-league debut with the St. Paul Saints, one of Brooklyn’s two Triple-A affiliates. At that time he acquired his nickname, Sandy, from veteran teammate Bert Haas, also a teammate with Havana. The resemblance to featherweight champ Saddler was only passing, but the label stuck over time, though many contemporary articles still called him Edmundo. In the United States, however, non-Spanish speakers typically accented the first syllable of his last name.14

In 129 games with the Saints, Amorós hit strongly (.337-19-78). That July, Andy High, the Dodgers’ chief scout, said he was worthy of a $150,000 bonus, given what young American high-schoolers were then receiving.15 About a month later, on August 21, 1952, the Dodgers announced that they were sending down pitcher Chris Van Cuyk and calling up Amorós — touted as “another Willie Mays”16 — for help in the stretch drive.

Sandy made his debut the next day, in the first game of a doubleheader at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. In his first at-bat, as a pinch-hitter in the ninth inning, he singled off Woody Main and came all the way around to score as the ball went through the legs of center fielder Brandy Davis. Apparently Amorós was right on the tail of Gil Hodges as he crossed the plate.

Amorós batted .250 in 44 at-bats the rest of the way — “change-ups fooled Miracle Wrists,” as Dodgers chronicler Roger Kahn noted.17 Still, he remained on Brooklyn’s roster for the World Series, appearing briefly as a pinch-runner in Game Six.

Amorós starred again that winter in Cuba. Along with 3 homers and 38 RBIs, he won the batting title with a .373 mark — the league’s highest in more than 30 years. Yet despite playing at home, Havana finished behind Santurce of Puerto Rico in the Caribbean Series; Edmundo went just 4-for-24.

For various reasons, Amorós spent the whole 1953 season with Brooklyn’s other Triple-A team, Montreal. He won the International League’s batting crown as well at .353, with 23 homers and 100 RBIs. Don Thompson, Jackie Robinson, and George Shuba saw most of the action in left field for Brooklyn.

The front office may have sought some more seasoning for Sandy, whose English was also still very limited — “Hokay” and “steak” were his key vocabulary words. Another factor is worth noting, though. On April 7, 1953, the New York Times observed, “Delayed for a time in Havana by the McCarran Act, Amorós hasn’t worn a Brooklyn uniform this spring. He has been working out at Vero Beach since his arrival.”18 The McCarran Internal Security Act of 1950 was a controversial law aimed at “subversives,” passed over President Truman’s veto while the Senate was in the grip of McCarthyism. Even though Communism was still several years away in Cuba, people around the world faced tighter curbs on admission to the United States, especially after the related McCarran-Walter Act was passed in 1952.

Unsavory racial implications were also visible. On days when Don Newcombe pitched, the Dodgers lineup had the potential for a majority of black players (Robinson at third instead of Billy Cox, Roy Campanella, and rookie second-baseman Jim Gilliam, as well as Sandy). Brooklyn had been a groundbreaking organization, but by that time, Branch Rickey was gone. Roger Kahn noted, “Actually, by this time the Dodgers were exceedingly cautious crusaders.”19

Sandy had another excellent winter in Cuba (.322-9-39), and then a strong spring with the Dodgers in 1954. This prompted further “poetic license” with the pronunciation of his surname as New York Mirror writer Dan Parker parodied the song “That’s Amore.”20 Amorós opened the 1954 season in Brooklyn, but the Dodgers sent him down to Montreal in mid-May when the time came to meet roster limits.

Though Dodgers management denied it, the possible racial motive again surfaced, as journalist John Lardner discussed in his May 10 story for Newsweek, “The 50 Per Cent Color Line.” Bill Roeder of the New York World-Telegram & Sun (who had separately remarked on Sandy’s habit of wiggling his wrists at the plate) also wrote of “an undercurrent of suspicion.” When Amorós returned in July, however, the majority-black lineup took the field for the first time in big-league history on July 17 at Milwaukee’s County Stadium. Jackie Robinson played third base. Six days later, Edmundo hit his first big-league homer, off Vic Raschi of the Cardinals.

The 1954 season was also notable for a controversy that developed later — Roberto Clemente’s contention that the Dodgers “hid” him in Montreal. Author Stew Thornley re-examined this generally accepted belief in the 2006 edition of SABR’s annual, The National Pastime. He quoted Canadian baseball historian Neil Raymond:

“What becomes apparent going through the Montreal papers daily (La Presse, The Gazette, The Star) is that this team was not perceived as a player development exercise,” maintained Raymond. “They were expected to win. Translation: Sandy Amorós’s at-bats were deemed a lot more valuable.” Indeed, Edmundo swung a hot bat before his recall (.352-14-50). His output for Brooklyn, largely against righty pitching, was good (.274-9-34).

Just after Christmas 1954, Amorós married Migdalia Castro, his childhood sweetheart from Matanzas.21 She may already have delivered their only child — articles from 1967 note daughter Eloisa’s age as 13.

Following a fifth straight fine season in Havana (.307-5-37), Sandy finally became the primary left fielder for Brooklyn in 1955. He posted career highs of 119 games and 388 at-bats. The numbers were not outstanding (.247-10-51), but his World Series action turned out to be special. Amorós was 4-for-12 in five games, and when he entered Game Seven in the sixth inning (as Jim Gilliam shifted from left to second), his peak moment was at hand.

Billy Martin had led off the bottom of the sixth with a walk, and Gil McDougald bunted his way on. This was Yankee broadcaster Mel Allen’s call as the dangerous Yogi Berra came to the plate:

“Johnny Podres on the mound. Dodgers leading 2-0. . . . The outfield swung away toward right. Sandy Amorós is playing way into left-center. Berra is basically a pull hitter.

“Here’s the pitch. Berra swings and he does hit one to the opposite field, down the left field line. . . . Sandy Amorós races over toward the foul line . . . and he makes a sensational, running, one-handed catch! He turns, whirls, fires to Pee Wee Reese. Reese fires to Gil Hodges at first base in time to double up McDougald. And the Yankees’ rally is stymied!”

When asked how he made the play, Sandy summed it up simply: “I dunno. I run like hell.” In addition to his superior speed, Amorós was also left-handed; righty Jim Gilliam said he would not have reached the slicing liner on his backhand. Yet according to winning pitcher Podres, “The big thing about it, though, more than the catch, was how he fired the ball back to Reese.” Podres added that Don Zimmer jokingly took credit for the turn of events because manager Walt Alston had pulled Zimmer for a pinch-hitter and inserted Amorós.22

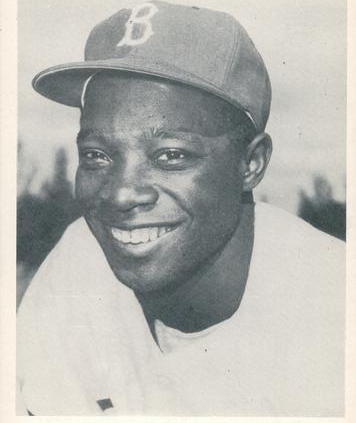

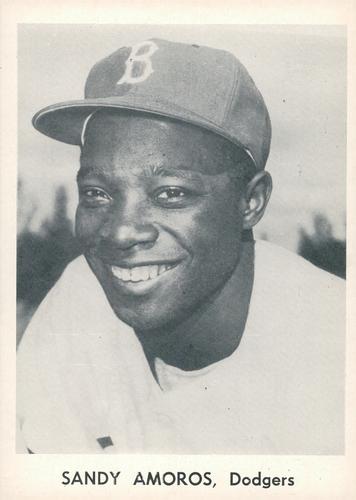

Life magazine published a splendid photo of Sandy smiling brilliantly around a Cuban cigar as he celebrated the victory. The Cuban press reveled even more.

“Amorós, hero of the year,” proclaimed Carteles. Bohemia published a full-page photograph of Amorós over the caption: “His performance in the World Series has produced intense joy in our nation.” His deeds signified a “triumph and corroboration for the quality of our sports” and “assure him a place of honor in the history of the pastime of Cuba.”23

Sandy spent his last winter with the Havana Reds in 1955-56, falling below .300 (.262-8-34). He enjoyed his best big-league season in 1956, though, hitting 16 homers and driving in 58 for Brooklyn in just 292 at-bats. In the World Series, however, he went cold, going just 1-for-19 in six games — with one crucial near-miss. In the fifth inning of Don Larsen’s perfect game, Amorós hooked a drive barely wide of the right-field foul pole.

Before the 1956-57 winter season, Havana traded Edmundo to Almendares for four players: infielder Héctor Rodríguez, outfielders Román Mejías and Óscar Sardiñas, and pitcher Raúl Sánchez. With the Alacranes (Scorpions), he suffered a poor season, hitting just .194 with 4 homers and 24 RBIs.

Sandy never could reach a higher level in Brooklyn. From the language standpoint, he had not made great progress, relying on support from Spanish-speaking teammates including Joe Black, Gilliam, and Campanella (Roy let him live on his yacht). Brooklyn fan Pete Trunk recalls that as a boy, “My crew of buddies and I always hated when Sandy was on Happy Felton’s Knothole Gang. We couldn’t understand one word he was saying!”

Still, Amorós remained a useful role player in 1957, platooning with Gino Cimoli in left (.277-7-26). He rebounded somewhat with Almendares that winter (.247-7-29). After 1957, though, Sandy saw little time in the majors. In March 1958, the Dodgers — by then in Los Angeles — put him on waivers. Authors Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt described the situation as “a bitter salary dispute,” noting also that “Sportswriter Bill Nunn, Jr., of the Pittsburgh Courier claimed the Dodgers had influenced other teams to ‘keep their hands off Amorós’ to punish him for refusing to sign for the same salary, $10,500, he had made the year before.”24

Passing through waivers unclaimed, Sandy returned to Montreal. It is not known whether he ever picked up much French, though it should have been easier for him. He had good years at Triple-A in both 1958 (.260-16-62) and 1959 (.301-26-79), plus two more middling winters for the Scorpions, highlighted by a return to the Caribbean Series in 1959 (7-for-21). Los Angeles finally recalled him for five games in September at the end of the ’59 season. However, Amorós was not on the postseason roster.

Sandy actually made the Dodgers roster out of spring training in 1960, but saw very limited duty. On May 7, Los Angeles traded him to the Detroit Tigers for Gail Harris. He remained with the Tigers as a seldom-used reserve for the rest of the year. On May 31, his pinch-hit homer off Dick Hall — the last of his 43 home runs in the big leagues — gave Detroit its only run in a 2-1 loss.

The Cuban professional league played its last season in the winter of 1960-61, and Sandy was there until the end with Almendares, going out with a respectable .288 average. His lifetime totals in Cuba across 11 seasons, subject to some uncertainty, were 49 homers, 312 RBIs, and a .281 average in 2,305 at-bats.

Amorós then spent 1961 with Denver in the American Association (.259-10-58). On March 18, 1962, the Tigers organization sold him and infielder Ossie Álvarez to the Mexico City Red Devils. Sandy played well (.305-13-71) — but his days on the field were over, as he hit a new obstacle.

Author Nicholas Dawidoff (perhaps best known for his book on Moe Berg, The Catcher Was a Spy) provided many insights on Sandy’s life in a feature he wrote for Sports Illustrated in July 1989. He described how things went downhill because of a run-in with El Líder Máximo, Fidel Castro.

“Castro decided to form an entire professional summer league in Cuba. He asked Amorós, who, as usual, was spending his offseason in Cuba, to stay home and manage one of the teams instead of returning to Mexico that summer. ‘I told Castro I didn’t know how to manage,’ says Amorós. ‘I could play, why would I want to manage?’ Privately, Amorós had qualms about working for the government. Castro did not take Amorós’s refusal lightly. He stripped Amorós of his ranch, car, all his assets and cash.”25

Sandy worked for himself as a mechanic, repairman, or whatever he could find.26 His reduced circumstances led to other problems, notes Roberto González Echevarría:

“For many players, the collapse of the Cuban League had tragic consequences. The diaspora began. Amorós, for instance . . . could not leave for many years, during which he became an alcoholic and eventually a diabetic. When he did leave, the Dodgers put him on their roster for the few days he needed for his pension.”27

That was in May 1967. John McHale, then assistant to Commissioner Spike Eckert, was behind the kind act. When the future Montreal Expos executive found out that Sandy was seven days short of qualifying, he mentioned it to Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi, who took it in turn to club owner Walter O’Malley. 28 There is a photo of Sandy — “penniless, bald and 30 pounds lighter than when he played for Brooklyn”29 — delivering the lineup card to home plate during his time at Dodger Stadium.

Sandy had been able to escape Cuba at last, thanks to the good offices of Armando Vásquez, his old comrade from home and the Negro Leagues.30 Catholic Charities of Brooklyn sponsored his visa, and Amorós got a job coaching baseball in a Catholic Youth Organization playground in New York City.31 But after the family arrived in the United States and the Dodgers lent their support, a sad sequence of events ensued, as Nicholas Dawidoff portrayed:

“In December 1967, Migdalia divorced him, taking Eloisa with her. After three years, the store he worked in [a TV shop in the South Bronx] burned down. For six months Amorós was unemployed, until a friend at the New York Post, who had connections in the office of New York Mayor John Lindsay, helped him get a job with the parks department in the Bronx. When Lindsay’s term was up so was Amorós’s. Two years of unemployment followed.”

In 1977, Amorós claimed his first pension check from major-league baseball and moved to Tampa, where he lived alone on the money he earned from a variety of menial jobs and from his pension.”32

By that time, Sandy was suffering greatly from leg pain owing to poor circulation from his diabetes. Doctors amputated part of his left leg in September 1987. Roberto González Echevarría offered another moving depiction of Sandy, “who was in no condition to be interviewed formally”:33

“I will never forget peering through a window of Edmundo Amorós’ apartment in Tampa, with Agapito Mayor [a Cuban pitcher], to see if the old hero of the 1955 World Series was awake. Every day, Mayor brought him a meal from a nearby restaurant with take-out service and cleaned up the apartment for him. I was deeply moved by Mayor’s kindness, which he displayed without fuss, as if he were performing the most routine of chores. Once inside we find a withered figure, missing a leg from the knee down (diabetes), and with the ashen color of poor health. He speaks softly of leaving Cuba, of getting an offer to play in some independent league in Canada because they still remembered him there from his salad days with the Montreal Royals. But he knew that he was through, he says. His artificial leg is propped up against the wall. A small television set blares with some adventure movie. Mayor is puttering about, picking up things, tidying up. He has run Amorós to the hospital several times. . . .”34

This was actually a step up from the worst conditions Sandy had faced. After his operation, fellow Cuban and Brooklyn Dodger Chico Fernández got the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) to supplement the meager $495 monthly pension with an additional $400 a month.35

Amorós was still capable of some travel, though, and many other friends still kept him in their minds and hearts. In February 1990, he went to Miami for a meeting. “The Federation of Professional Cuban Baseball Players in Exile hosted their own reception in conjunction with the Caribbean Series of Baseball. The meeting room was full of baseball history. Cuban greats like Tony Oliva, José Tartabull, and Sandy Amorós gathered to talk about yesterday and today.”36

As of 1991, Sandy still lived in Tampa.37 In the last year of his life, though, he moved to Miami to live with his daughter Eloisa and her four children. The New York Times wrote another feature article on him in June 1992, shortly before he was to travel back to Brooklyn as guest of honor at the Coney Island Sports Festival. An autograph signing and memorabilia auction were set up, with the lion’s share of the proceeds intended for his benefit. June 20 was scheduled as Sandy Amorós Day in Brooklyn.38

Alas, he never made it north. He was stricken with pneumonia on June 16 and entered Miami’s Jackson Memorial Hospital.39 Though it looked as though he was rallying after he went on a respirator,40 Sandy declined and eventually passed away on June 27. He was buried in Woodlawn Park North Cemetery and Mausoleum in Miami.

More than 60 years after his greatest feat, Edmundo Amorós is still remembered in the United States and celebrated as a hero in Cuba. Yet beyond the field, through good times and hardships, there was always one constant about this proud but modest man. Said his lawyer, Rafael Sánchez:

“From the days when he played until now, he’s always had that wonderful smile. You’ll look at him and just marvel at that smile.”41

Sources

SABR Minor League Database

Professional Baseball Player Database V6.0

www.retrosheet.org

www.findagrave.com

Photo Credit

Sandy Amoros, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Edgar Williams. “Sandy Amoros — He Got!” Baseball Digest, October 1954: 76.

2 Peter Golenbock. Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers (New York: McGraw-Hill/Contemporary, 2000 edition).

3 Although various baseball reference books say that Amorós was born in Havana, the more reliable sources are Cuban. Matanzas and the year 1930 (see note 9) are listed in Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2003). All Cuban statistics noted here also come from this source.

4 Roberto González Echevarría. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999: 130).

5 Roger Kahn. The Era, 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002: 325).

6 Williams, op. cit.: 75.

7 Originally in New York Daily News, July 20, 1972. See also: Jules Tygiel. Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997 expanded edition), 342. Samuel Octavio Regalado. Viva Baseball! Latin Major Leaguers and Their Special Hunger (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 50. Joseph Dorinson, et al. Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1999), 157.

8 “Otra Estrella del ‘Baseball,’ ” El Nuevo Herald (Miami, Florida), April 3, 2004: 2E.

9 The April 1953 issue of Baseball Digest is an early U.S. reference showing the 1930 date.

10 Peter C. Bjarkman. Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005), 470.

11 Brent P. Kelley. “I Will Never Forget”: Interviews with 39 Former Negro League Players (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 178. For a picture of Amorós as a New York Cuban, see The Kingston Daily Freeman, August 23, 1950: 14.

12 Ángel Torres. La Leyenda Del Béisbol Cubano: 1878-1997 (Self-published, 1997).

13 Williams, op. cit.: 76.

14 At least one place, the 1956 edition of J.G. Taylor Spink’s Baseball Register, had it right: Am-or-OS.

15 St. Petersburg Times, July 17, 1952.

16 “Brooklyn Dodgers Call Up Rookie Outfielder,” Fresno Bee, August 21, 1952: 35.

17 Roger Kahn. The Boys of Summer (New York: Harper & Row, 1973 paperback edition), 167.

18 “Amoros Goes to Montreal,” New York Times, April 7, 1953: 36.

19 Kahn, The Boys of Summer, loc. cit.

20 David Maraniss. Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 42.

21 Williams, op. cit.: 78.

22 Bob Bennett, John Bennett Jr., and Robert S. Bennett. Johnny Podres: Brooklyn’s Yankee Killer (Bloomington, Indiana: Rooftop Publishing, 2007), 26, 44.

23 Louis A. Pérez, Jr. On Becoming Cuban: Identity, Nationality, and Culture (New York: Harper Perennial, 2001), 262.

24 Larry Moffi and Jonathan Kronstadt. Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers 1947-1959 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1994), 73.

25 Nicholas Dawidoff. “The Struggles Of Sandy A,” Sports Illustrated, July 10, 1989.

26 Milton Richman. “Stripped Of Everything In Cuba, Amoros Hopes for New Life Here,” United Press International, May 5, 1967. See also: “Amoros Arrives From Cuba Stripped of All He Had Earned,” New York Times, April 28, 1967: 47. “Cubans Took House, Auto From Amoros,” Washington Post, May 13, 1967: E2.

27 González Echevarría, op. cit.: 351.

28 Joe Heiling. “Switch: A Great Play FOR Amoros,” Baseball Digest, July 1967: 75.

29 Sports Illustrated, May 8, 1967.

30 Adrian Burgos, Jr. Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2007), 218.

31 Heiling, op. cit., loc. cit.

32 Dawidoff, op. cit.

33 González Echevarría, op. cit., 406.

34 González Echevarría, op. cit., 403.

35 Dawidoff, op. cit.

36 Dave Hoekstra. “Cuban stars have far to go for fame,” Chicago Sun-Times, February 12, 1990.

37 Bruce Lowitt. “One Shining Moment: In The Years Since Dramatic Catch, Fate Has Frowned On Series Hero,” St. Petersburg Times, April 27, 1991: 4C.

38 Charles Nobles. “Hard Times for Amoros, but Pride Remains,” New York Times, June 7, 1992.

39 Robert McG. Thomas, Jr. “Sandy Amoros, World Series Star for Dodgers in 1955, Dies at 62,” New York Times, June 28, 1992.

40 “Amorós Listed in Critical Condition,” New York Times, June 19, 1992.

41 Nobles, op. cit.

Full Name

Edmundo Amorós Isasi

Born

January 30, 1930 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

June 27, 1992 at Miami, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.