Bill Tuttle

“A real man is Bill Tuttle – someone who will stand up and tell the truth.” – Joe Garagiola, 1998[1]

Bill Tuttle was a capable journeyman outfielder who played during 11 seasons in the American League (1952; 1954-63). He had his best year at age 25, manning center field for the 1955 Detroit Tigers. He appeared in all 154 games that year and hit 14 of his 67 big-league homers. As his 1959 Topps baseball card noted, however, “He doesn’t try for the long ball but is a clever spray hitter.” That thumbnail sketch opened by describing him as “one of the finest defensive flychasers in the Junior Circuit.”

Bill Tuttle was a capable journeyman outfielder who played during 11 seasons in the American League (1952; 1954-63). He had his best year at age 25, manning center field for the 1955 Detroit Tigers. He appeared in all 154 games that year and hit 14 of his 67 big-league homers. As his 1959 Topps baseball card noted, however, “He doesn’t try for the long ball but is a clever spray hitter.” That thumbnail sketch opened by describing him as “one of the finest defensive flychasers in the Junior Circuit.”

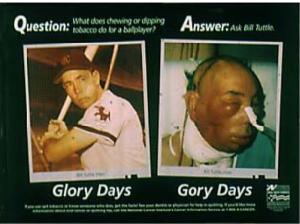

In later life, however, a grim side of Tuttle’s baseball experience came to the fore. He was often pictured in his playing days with a big chaw of tobacco in his cheek. After developing oral cancer and undergoing disfiguring surgery, he joined Joe Garagiola in the catcher-turned-broadcaster’s campaign against spit tobacco. “The ballplayers see my face and listen,” said Tuttle in 1997.[2]

Tuttle died at age 69 in July 1998 following a long, recurring battle with the disease. His passing was noted in obituaries in the nation’s leading newspapers.[3] A poignant story about him that December in the international journal Tobacco Control called him a crusader. As author Jane Imholte put it: “Immense guilt and a sense of responsibility drove him.”[4]

* * *

Bill Tuttle was born on July 4, 1929, in Elmwood, Illinois. Baseball references came to show his name as William Robert, but as he said in a May 1954 interview, “My birth certificate says merely ‘Bill Tuttle.’ Curious, I investigated, and my dad told me I had been christened Bill.”[5] A 1958 story said, “[his] legal handle is Bill Bob Tuttle.”[6]

Bill grew up in Cramer, a village in central Illinois several miles south of Elmwood and about 20 miles west of Peoria. His father, Wilbur F. Tuttle, operated a general store in Cramer. Wilbur married Elma (née Wasson) in 1923.[7] They had one other child before Bill, a daughter named Jane. The 1940 Census shows “Billy Bob” as a 10-year-old fourth-grader.

According to the same May 1954 interview, Wilbur Tuttle played some semipro ball around Elmwood but had little to do with his son’s baseball career. Bill credited his maternal uncle, Joe Wasson, with encouraging him even though Wasson never played himself or coached his nephew. The youth played a lot of ball locally, although his grade school – in the town of Farmington, a few miles west of Cramer – did not have a team.[8]

Tuttle went to Farmington High School, where he played baseball, softball, basketball, and football. At that time, he viewed himself as a better football player. He was the quarterback of a team that was unbeaten for two straight years.[9]

Tuttle initially went to college at the University of Illinois. As he later recalled, though, “There were just too many good football players to suit me. So I quit after one semester.”[10]

He transferred to Bradley University in Peoria. During his three-year baseball career there, he hit .338 in 86 games. The Braves won the East Division of the Missouri Valley Conference (MVC) in all three years, as well as the MVC playoffs in 1950. That earned Bradley a trip to the 1950 College World Series. The following month, on July 16, 1950, Tuttle married his high school sweetheart, Lucille Hubbard.[11] They had four children: Patricia, Rebecca, Robert, and James.

Tuttle continued to play football at Bradley. Standing six feet even and weighing 190 pounds, he played end. He was also good enough to be part of the Braves’ nationally ranked basketball program before focusing on baseball and football.[12]

Tuttle was captain of the Bradley baseball team in 1951. In addition to his play in the outfield, his defense at second base also earned praise.[13] After graduating, he signed with the Detroit Tigers. The scout was George Moriarty. It was the era of big bonuses, and by some accounts, Tuttle reportedly got $75,000.[14] By others, the figure was less lavish: $12,000 to $25,000.[15] He’d negotiated with a Yankees scout, worked out with the Cubs at Wrigley Field, and also had some talks with the White Sox. But after a workout at Briggs Stadium, the young man felt that the Tigers offered the best opportunity – not to mention the best terms.[16]

The prospect spent his first professional season with Davenport (Iowa) of the Class B Three-I League. He enjoyed modest success, hitting .252 with 3 homers in 84 games. As he put it in 1954, “I made the acquaintance of a nasty little stranger known as Curve Ball.”[17]

In 1952, however, Tuttle zoomed up the ladder. He was back at Davenport to start the year but won promotion to Williamsport in the Eastern League (Class A). He then vaulted past Double-A and joined Buffalo in the International League (Class AAA). With the Bisons, Tuttle got an extended trial at shortstop (but would never play there again as a pro). He capped his ascent with a seven-game look-see from the big club.

After a full year of seasoning in Buffalo in 1953, Tuttle’s big-league career began in earnest in 1954. That January, Bradley inducted Tuttle – who was also MVP of the football team in 1950 – into its Athletics Hall of Fame.

The Tigers remade their outfield in 1954. Incumbent center fielder Jim Delsing moved to left. Tuttle took over in center and 19-year-old Al Kaline was on his other flank in right; the rookies became known as “the jackrabbits.”[18] The label was attached to them by their manager, Fred Hutchinson (who would also come to symbolize anti-cancer efforts).[19]

The people of Farmington took great pride in Tuttle. That April, a Farmington man wrote to The Sporting News to refute any idea that the outfielder was from Peoria, saying, “since this community never has sent a player to the majors, we naturally want the credit for it when Bill makes good.”[20] On August 15, about 400 fans from the town took a special train to Chicago to see him perform against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park. He didn’t let them down, going 3-for-9 as the Tigers swept the doubleheader.[21]

Tuttle and Kaline remained two-thirds of Detroit’s starting outfield through 1957. However, while Kaline blossomed into a perennial All-Star and Hall of Famer, Tuttle’s offensive totals dipped from his career highs in 1955. In January 1957, Tigers beat writer Watson Spoelstra reported talk that the outfielder was “eating himself out of the league.” That story called Tuttle the club’s biggest disappointment of 1956.[22]

It was also during his time with the Tigers – in 1955, while sidelined with an injury – that Tuttle was introduced to chewing tobacco by teammate Harvey Kuenn. Looking back in 1996, Tuttle’s second wife, Gloria, said, “We’re certainly not blaming Harvey Kuenn. But if Bill hadn’t taken that first chew, we wouldn’t be here today.”[23] Kuenn, who was also frequently pictured with a chaw-distended cheek, had died at age 58 in 1988. For much of his later life he was plagued by health problems stemming from poor circulation – which can be correlated with chewing tobacco.

In November 1957, Detroit sent Tuttle to the Kansas City Athletics as part of a 13-player trade. The following month, he said, “I’ve never gotten over my yen for the infield and third base in particular. . .I can’t get rid of the thought I could play third base. I’d like the chance to find out.”[24] That eventually came true a few years later, but not with the A’s. Tuttle was KC’s primary center fielder from 1958 through mid-1961. Although his power numbers were modest, he did hit a career-high .300 in 1959.

On June 1, 1961, Kansas City traded Tuttle to the Minnesota Twins for Reno Bertoia and Paul Giel. Giel pitched in one game for the A’s and retired; the Twins wound up sending cash compensation to Kansas City. During the remainder of the season, Tuttle finally got his shot at playing third base and logged the most innings of anyone on the club that year at the hot corner. He was deemed an acceptable fill-in.[25]

“I’ll play where they want me,” said Tuttle that offseason, “but I still have a yen to continue my improvement at third base.”[26] As it developed, he moved back to the outfield for Minnesota in 1962 and took a reserve role. Although he got into 110 games, he started just 27 behind Lenny Green in center and Bob Allison in right. He came to the plate only 148 times. After the season, he asked for a trade, saying, “I couldn’t take another season of playing ninth-inning caddy.”[27]

No deal transpired. By then 33, Tuttle was on the Twins’ Opening Day roster in 1963 but played very sparingly (just four plate appearances in 16 games). Minnesota released him on May 21, 10 days after his last outing in the majors.

At that time, Tuttle was living in the Kansas City suburb of Raytown, and he was allowed to work out with the A’s to stay in shape while hoping to catch on somewhere else.[28] That opportunity came in June, when the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League released 41-year-old Jim Rivera. Tuttle played some at third base in addition to the outfield for the Boston Red Sox affiliate. He also made his first two pitching appearances as a pro.

Tuttle returned to Seattle in 1964 but appeared in only 45 games after suffering a broken collarbone and two fractured ribs in an outfield collision with Barry Shetrone on May 24.[29]

In the spring of 1965, Tuttle was signed and released by the Atlanta Crackers, then the top farm club of the Milwaukee Braves. He then joined Syracuse, also in the International League, and played there for the next three seasons. The Chiefs were affiliated with the Tigers in 1965 and ’66 but became the Yankees’ top farm team in ’67.

In his final season as a pro, Tuttle made three successful pitching appearances covering 13 innings. Amid a thicket of doubleheaders in June, Syracuse got Tuttle certified as a pitcher (IL rules then permitted one non-pitcher to be registered for mound duty). Tuttle said, “I threw mostly fastballs and a few sliders. I tried a forkball but got to laughing so hard I bounced it 20 feet in front of the plate.”[30]

Tuttle and Lucille divorced sometime around 1964 or 1965. One may conjecture that the marriage ended because Bill didn’t want to quit baseball. In November 1965, he married Gloria Niebur and adopted her three daughters: Debra, Kimberly, and Cindy.[31]

Tuttle’s pro career ended when he was 38. He returned with his second family to the Farmington area, where he ran an establishment called Tuttle’s Supper Club. He also worked for the Hiram Walker distillery in Peoria, which was known as a center of whiskey production for decades. From 1982 to 1987, he was an assistant pro at a golf club.[32] Debi Heyer, one of Tuttle’s daughters from his second marriage, noted, “He did not get his full degree at Bradley University and never went back to get it, unfortunately. That meant that he could not teach, or coach, etc., so he took odd jobs.”[33]

In his leisure time, Tuttle remained involved in baseball, managing in Peoria’s Sunday Morning League, in which he had also played as a young man.[34] He was still active as a player too, as Debi confirmed. “I loved going to watch him play,” she said. “Remembering that brings joy to my heart.”[35]

In 1981, Bill and Gloria moved to Minnesota, near Anoka (about 20 miles north of Minneapolis). They wanted to be close to Debi, whose oldest son had congenital heart disease and needed open heart surgery. Furthermore, daughter Cindy had also moved to Minnesota. “My dad went to every single sporting event my three boys were in,” said Debi, “no matter the age, sport, or location. He was dearly loved by all of us.”[36]

Tuttle’s cancer diagnosis came in October 1993. Gloria noticed a lump in his cheek and asked him, “Have you started chewing inside the house now?”[37] But it wasn’t tobacco. Oddly enough, the tumor developed on the right side of his face, even though he had always put his chaw in his left cheek.[38]

As the medical battle proceeded, costs were high and mounting. Tuttle was by no means well off financially, and according to Debi, his insurance would not cover his cancer – nor did he have coverage through Major League Baseball.[39]

Enter Joe Garagiola. In 1986, MLB formed the Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) to help “members of the Baseball Family in need.” Garagiola was one of the team’s founders and its president from 1989 through 2002.[40] He had heard of Tuttle’s crisis from Gloria, according to Leonard Koppett’s 1999 article for SABR’s Baseball Research Journal.[41] Garagiola also said in a statement before a U.S. Senate committee in 1998 that Gloria had called him.[42]

According to writer Jane Imholte, “Garagiola called the Tuttles on Christmas Eve 1993 and told them his organisation would cover all medical expenses. In return, he asked for a favour.”[43] That request was related to Garagiola’s other core issue: his opposition to tobacco in all forms. In particular, he sought to educate players and coaches about the dangers of smokeless tobacco – or, to use Garagiola’s preferred term, “spit tobacco.”

Once he was well enough, Tuttle had already been speaking to children in schools about the perils of chewing and dipping. He then joined Garagiola – as well as two stars of the highest magnitude, Hank Aaron and Mickey Mantle – in October 1994 for an address from the National Press Club in Washington. The event also featured the U.S. Surgeon General, Dr. Joycelyn Elders, and National League President Leonard Coleman.[44]

This press conference was under the aegis of the National Spit Tobacco Education Program (NSTEP), established by a group called Oral Health America. In August 1995, again on behalf of NSTEP, Garagiola addressed the nation about his campaign in front of the White House (Bill Clinton was then President). As part of his talk, he displayed a picture of Tuttle recovering from operation #3.[45] Later, that same image was used in a jarring poster.

NSTEP’s efforts and Tuttle’s role therein received much attention in the press. Stories chronicled various notable names and their struggles to kick the habit, including Curt Schilling, Pete Harnisch, and Len Dykstra, the “poster boy” for chewing in the 1990s. Garagiola’s campaign broadened to include an annual tour of clubhouses during spring training; Tuttle agreed to accompany Garagiola on these visits and speak. At least one other active player then directly credited seeing Tuttle with his decision to quit using: catcher Gregg Zaun.[46] Yet even this strong visual deterrent couldn’t stop John Gibbons, then a Mets minor-league manager. Only in 2014, after the death of Tony Gwynn from parotid cancer – which Gwynn attributed to his spit tobacco use – could Gibbons bring himself to change.[47]

Threaded throughout these stories were graphic depictions of the suffering that Tuttle endured. This included the series of complex operations, the reconstruction of his face – “he still looked like a dried-up apple,” said Gloria[48] – the radiation treatments and chemotherapy, the tubes he had in his nose and stomach, and more. He went into remission for stretches, but the cancer kept coming back.

On May 19, 1998, Minnesota celebrated “Bill Tuttle Day” at the state capitol building in St. Paul. Anne Barry, Commissioner of Minnesota’s Department of Health, was there along with the Tuttles and Joe Garagiola. The Twins honored Tuttle before that night’s game at the Metrodome in Minneapolis.[49] Ill as he was, he still summoned the strength to throw out the first pitch, as his daughter Debi related. “I was the one to walk him onto the field. We were walking together, him slow, crouched over, weak – but as soon as he stepped out on the field, his head was held high, his back straight, his manner strong and confident. It was an amazing transformation I will never forget.”[50]

A little over two months later, on July 27, Bill Tuttle’s battle came to an end. “Eventually, Bill lost most of his voice,” Jane Imholte related. “He communicated with pen and paper. Two days before he died, he wrote Gloria a note: ‘I know what I did was wrong and I’m so sorry I hurt everybody. But maybe I can show them how sorry I am by teaching other people.’”[51]

Along with Gloria, Tuttle was survived by their three daughters as well as the four children from his previous marriage and 17 grandchildren.[52] He was buried at Big Lake Cemetery in Big Lake, Minnesota.

Oral Health America established the Bill Tuttle Award, given annually to “individuals or groups who distinguish themselves in the ongoing fight for tobacco awareness and education.”[53] The first recipients were Bill and Gloria, as Bill noted in a letter to the U.S. Senate written on May 18, the day before his honors at the Metrodome. On July 31, Senator Dick Durbin of Illinois gave a short speech about Tuttle and asked that the letter be printed in the Congressional Record.[54]

In September 1999, Gloria Tuttle filed a lawsuit against several smokeless tobacco manufacturers and their trade association. Among them was Lorillard Tobacco Company, producer of Bill’s chew of choice, Beech-Nut. The district court ruled in favor of the defendants, and Mrs. Tuttle appealed. In 2004, the appellate court upheld the district court’s judgment, concluding that the widow’s claims were legally insufficient, “for want of admissible proof of causation and reliance.”

Gloria Tuttle lived until 2006. As her obituary noted, “After Bill’s death, Gloria continued to speak passionately and tirelessly about the hidden epidemic of spit tobacco.” She remarried, to a man named Bud Fischer, and in 2005 the Gloria Tuttle Fischer Foundation was established to continue her work in promoting tobacco cessation.[55]

In 2020, Oral Health America became part of the Authority Dental Organization. Four years previously, Joe Garagiola had died at the age of 90. Before that (2011), he had expressed deep frustration with the lack of a spit tobacco ban in Major League Baseball.[56]

Nonetheless, on went the crusade that he, Bill, and Gloria Tuttle helped wage – and in November 2016, eight months after Garagiola’s death, a breakthrough came. As part of the new Collective Bargaining Agreement, MLB did at last ban the use of smokeless tobacco among new players, although current players were grandfathered in – a bridge that Garagiola had suggested back in 1995. As of 2023, according to the Tobacco-Free Baseball website, over half the stadiums in the majors (16 of 30) are completely tobacco-free as a result of state and local laws.

Still, the addictive power of nicotine is visible in baseball. A 2023 report discussed big-leaguers’ widespread use of tobacco-free nicotine pouches, the most popular being a Swedish product line called Zyn.[57] Bill Tuttle knew how profound this grip is. As he said in 1996, “If they assured me I had a 100% chance of not getting cancer again, I’d have some chew in my mouth tomorrow.”[58]

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Debi Lutz Tuttle Heyer, daughter of Bill Tuttle.

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz. Thanks also to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee and Stew Thornley of SABR’s Halsey Hall Chapter.

Sources

In addition to those cited in the Notes, this story also made use of:

comc.com (baseball card database)

LA84.org – Bill Tuttle’s Sporting News player contract card

CourtListener.com – summary of Gloria Tuttle’s legal battle

Bradleybraves.com – Bill Tuttle page

Bradleybraves.com – Athletics Hall of Fame (T-V))

Notes

[1] “Tobacco Legislation and the Food and Drug Administration and Smokeless Tobacco Issues in the Proposed Settlement,” Hearing Before the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, United States Senate, March 17, 1998, Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office (1999): 50.

[2] “He’s Spitting Mad,” Sports Illustrated, April 21, 1997.

[3] Two prime examples are Richard Goldstein, “Bill Tuttle, 69, an Opponent of Use of Chewing Tobacco,” New York Times, July 30, 1998, and “Tuttle Loses Battle to Cancer,” Los Angeles Times, July 29, 1998.

[4] Jane Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle,” Tobacco Control, December 1, 1998.

[5] J.G. Taylor Spink, “Looping the Loops,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1954: 4.

[6] Oscar Ruhl, “From the Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1958: 13.

[7] “Wilbur F. Tuttle,” Galesburg (Illinois) Register-Mail, July 29, 1977.

[8] Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

[9] Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

[10] “Bill Tuttle is Mystified by His Near .300 Batting Mark after .276 Season in Buffalo,” United Press, August 4, 1954.

[11] Spink, “Looping the Loops.” They are pictured next to each other in the 1947 Farmington High yearbook.

[12] John O’Donnell, “Third of Sum Was Paid to Billy Davidson by Tribe,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1951: 17. One may surmise that Tuttle played on the freshman team; his name does not appear in the Bradley varsity basketball stats for the seasons from 1948-49 through 1950-51, as shown on Sports-reference.com.

[13] O’Donnell, “Third of Sum Was Paid to Billy Davidson by Tribe.”

[14] “Five Kids Who Got Bonuses Over 40 Grand Now in I-I-I,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1951: 4.

[15] O’Donnell, “Third of Sum Was Paid to Billy Davidson by Tribe.”

[16] Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

[17] Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

[18] “Kids Tuttle and Kaline Nail Two at Plate in Succession,” The Sporting News, June 16, 1954: 14.

[19] Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

[20] “Tuttle from Farmington, Ill.,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1954: 14.

[21] “Major League Flashes,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1954: 21.

[22] Watson Spoelstra, “Tiger Prexy Turns on Extinguisher in Kaline Pay Flareup,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1957: 11.

[23] Bill Koenig, “A painful portrait,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, June 6, 1996.

[24] Ernest Mehl, “Tuttle Eying Shot at Third with Kaycee,” The Sporting News, December 25, 1957: 8.

[25] Tom Briere, “Twin Protection in Middle Garden Eases Twins’ Woes,” The Sporting News, January 3, 1962: 27.

[26] Tom Briere, “Twins Invite Farm-Club Pilots to Join Huddles at Orlando Base,” The Sporting News, January 24, 1962: 22.

[27] Tom Briere, “Tuttle Nixes Bench Duty; Seeks Swap,” The Sporting News, November 10, 1962: 8.

[28] Joe McGuff, “Poet Ed Charles Has No Quarrels with Soph Jinx,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1963: 32.

[29] “Coast Clippings,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1964: 44.

[30] Larry Kimball, “What’ll Tuttle Think of Next? Vet Makes Pitching Debut at 37,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1967: 35.

[31] E-mail from Debi Heyer to Rory Costello July 25, 2023 (hereafter “Heyer e-mail”). The 2004 obituary of Luciile’s second husband, Frank Rankin, noted that they had been married for 35 years and remained in Missouri.

[32] See Tuttle’s entry in Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s, Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Company (2004): 405.

[33] Heyer e-mail.

[34] “Remember When: July 16 in Journal Star sports history,” Peoria Journal Star, July 15, 2018. “A Legendary League Celebrating a Century of Baseball,” Peoria Magazine, July 2015 (https://www.peoriamagazine.com/archive/ibi_article/2015/legendary-league-celebrating-century-baseball/).

[35] Heyer e-mail.

[36] Heyer e-mail.

[37] Dave Kindred, “Huge potholes on Tobacco Road,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1996: 6.

[38] Koenig, “A Painful Portrait.”

[39] Heyer e-mail.

[40] “Remembering Joe Garagiola Sr.,” MLB.com, undated (https://www.mlb.com/baseball-assistance-team/remembering-joe-garagiola).

[41] Leonard Koppett, “The Fight Against Spit Tobacco, Baseball Research Journal 27, Society for American Baseball Research (1999): 136.

[42] “Tobacco Legislation and the Food and Drug Administration and Smokeless Tobacco Issues in the Proposed Settlement”: 49.

[43] Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle.”

[44] Tobacco Product Use | C-SPAN.org (October 6, 1994). Tuttle speaks for a little over 13 minutes, starting at the 38:20 mark.

[45] Joe Garagiola campaigning against spit tobacco by baseball players & teen smoking | C-SPAN.org, August 11, 1995. The photo is in Garagiola’s hand throughout; he holds it up for the camera from 1:22 through 1:42.

[46] “Backup Catcher Calls It Quits,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel, April 15, 1997.

[47] John Lott, “Campaign to Snuff Out Smokeless Tobacco in Baseball Intensifies,” VICE, June 16, 2016 (https://www.vice.com/en/article/mg8q4v/campaign-to-snuff-out-smokeless-tobacco-in-baseball-intensifies).

[48] Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle.”

[49] Information courtesy of SABR member Stew Thornley, who works for the Minnesota Department of Health and attended the events.

[50] Heyer e-mail.

[51] Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle.”

[52] Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle.”

[53] “Former Major Leaguer Bill Tuttle Dies of Cancer,” Associated Press, July 29, 1998.

[54] Congressional Record – Senate, S9613, July 31, 1998 (congress.gov).

[55] “Gloria Tuttle (Niebur) Fischer,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, August 20, 2006.

[56] Adam Kilgore, “Strasburg attempting to shut out tobacco,” Washington Post, January 31, 2011. This story discussed pitcher Stephen Strasburg (then just 22) and his effort to kick his spit tobacco addiction following the cancer diagnosis of his college coach, Tony Gwynn.

[57] Jake Mintz, “MLB players turning to nicotine pouches amid tobacco bans,” Fox Sports, March 3, 2023 (https://www.foxsports.com/stories/mlb/mlb-players-turning-to-nicotine-pouches-amid-tobacco-bans).

[58] Koenig, “A Painful Portrait.”

1 “Tobacco Legislation and the Food and Drug Administration and Smokeless Tobacco Issues in the Proposed Settlement,” Hearing Before the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation, United States Senate, March 17, 1998, Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office (1999): 50.

2 “He’s Spitting Mad,” Sports Illustrated, April 21, 1997.

3 Two prime examples are Richard Goldstein, “Bill Tuttle, 69, an Opponent of Use of Chewing Tobacco,” New York Times, July 30, 1998, and “Tuttle Loses Battle to Cancer,” Los Angeles Times, July 29, 1998.

4 Jane Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle,” Tobacco Control, December 1, 1998.

5 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Looping the Loops,” The Sporting News, May 26, 1954: 4.

6 Oscar Ruhl, “From the Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1958: 13.

7 “Wilbur F. Tuttle,” Galesburg (Illinois) Register-Mail, July 29, 1977.

8 Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

9 Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

10 Spink, “Looping the Loops.” They are pictured next to each other in the 1947 Farmington High yearbook.

11 John O’Donnell, “Third of Sum Was Paid to Billy Davidson by Tribe,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1951: 17. One may surmise that Tuttle played on the freshman team; his name does not appear in the Bradley varsity basketball stats for the seasons from 1948-49 through 1950-51, as shown on Sports-reference.com.

12 O’Donnell, “Third of Sum Was Paid to Billy Davidson by Tribe.”

13 “Five Kids Who Got Bonuses Over 40 Grand Now in I-I-I,” The Sporting News, June 20, 1951: 4.

14 O’Donnell, “Third of Sum Was Paid to Billy Davidson by Tribe.”

15 Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

16 Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

17 “Kids Tuttle and Kaline Nail Two at Plate in Succession,” The Sporting News, June 16, 1954: 14.

18 Spink, “Looping the Loops.”

19 “Tuttle from Farmington, Ill.,” The Sporting News, April 21, 1954: 14.

20 “Major League Flashes,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1954: 21.

21 Watson Spoelstra, “Tiger Prexy Turns on Extinguisher in Kaline Pay Flareup,” The Sporting News, January 16, 1957: 11.

22 Bill Koenig, “A painful portrait,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, June 6, 1996.

23 Ernest Mehl, “Tuttle Eying Shot at Third with Kaycee,” The Sporting News, December 25, 1957: 8.

24 Tom Briere, “Twin Protection in Middle Garden Eases Twins’ Woes,” The Sporting News, January 3, 1962: 27.

25 Tom Briere, “Twins Invite Farm-Club Pilots to Join Huddles at Orlando Base,” The Sporting News, January 24, 1962: 22.

26 Tom Briere, “Tuttle Nixes Bench Duty; Seeks Swap,” The Sporting News, November 10, 1962: 8.

27 Joe McGuff, “Poet Ed Charles Has No Quarrels with Soph Jinx,” The Sporting News, June 15, 1963: 32.

28 “Coast Clippings,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1964: 44.

29 Larry Kimball, “What’ll Tuttle Think of Next? Vet Makes Pitching Debut at 37,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1967: 35.

30 E-mail from Debi Heyer to Rory Costello July 25, 2023 (hereafter “Heyer e-mail”). The 2004 obituary of Luciile’s second husband, Frank Rankin, noted that they had been married for 35 years and remained in Missouri.

31 See Tuttle’s entry in Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s, Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Company (2004): 405.

32 Heyer e-mail.

33 “Remember When: July 16 in Journal Star sports history,” Peoria Journal Star, July 15, 2018. “A Legendary League Celebrating a Century of Baseball,” Peoria Magazine, July 2015 (https://www.peoriamagazine.com/archive/ibi_article/2015/legendary-league-celebrating-century-baseball/).

34 Heyer e-mail.

35 Heyer e-mail.

36 Dave Kindred, “Huge potholes on Tobacco Road,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1996: 6.

37 Koenig, “A Painful Portrait.”

38 Heyer e-mail.

39 “Remembering Joe Garagiola Sr.,” MLB.com, undated (https://www.mlb.com/baseball-assistance-team/remembering-joe-garagiola).

40 Leonard Koppett, “The Fight Against Spit Tobacco, Baseball Research Journal 27, Society for American Baseball Research (1999): 136.

41 “Tobacco Legislation and the Food and Drug Administration and Smokeless Tobacco Issues in the Proposed Settlement”: 49.

42 Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle.”

43 Tobacco Product Use | C-SPAN.org (October 6, 1994). Tuttle speaks for a little over 13 minutes, starting at the 38:20 mark.

44 Joe Garagiola campaigning against spit tobacco by baseball players & teen smoking | C-SPAN.org, August 11, 1995. The photo is in Garagiola’s hand throughout; he holds it up for the camera from 1:22 through 1:42.

45 “Backup Catcher Calls It Quits,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel, April 15, 1997.

46 John Lott, “Campaign to Snuff Out Smokeless Tobacco in Baseball Intensifies,” VICE, June 16, 2016 (https://www.vice.com/en/article/mg8q4v/campaign-to-snuff-out-smokeless-tobacco-in-baseball-intensifies).

47 Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle.”

48 Information courtesy of SABR member Stew Thornley, who works for the Minnesota Department of Health and attended the events.

49 Heyer e-mail.

50 Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle.”

51 Imholte, “Anti-spit tobacco crusader Bill Tuttle.”

52 “Former Major Leaguer Bill Tuttle Dies of Cancer,” Associated Press, July 29, 1998.

53 Congressional Record – Senate, S9613, July 31, 1998 (congress.gov).

54 “Gloria Tuttle (Niebur) Fischer,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, August 20, 2006.

55 Adam Kilgore, “Strasburg attempting to shut out tobacco,” Washington Post, January 31, 2011. This story discussed pitcher Stephen Strasburg (then just 22) and his effort to kick his spit tobacco addiction following the cancer diagnosis of his college coach, Tony Gwynn.

56 Jake Mintz, “MLB players turning to nicotine pouches amid tobacco bans,” Fox Sports, March 3, 2023 (https://www.foxsports.com/stories/mlb/mlb-players-turning-to-nicotine-pouches-amid-tobacco-bans).

57 Koenig, “A Painful Portrait.”

Full Name

William Robert Tuttle

Born

July 4, 1929 at Elmwood, IL (USA)

Died

July 27, 1998 at Anoka, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.