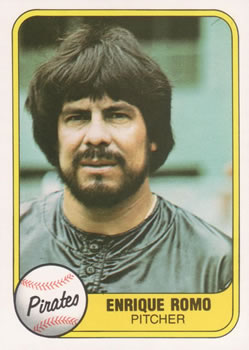

Enrique Romo

Pitching isn’t just about throwing hard. It’s about contrast and ball movement, and Enrique Romo kept hitters off stride and guessing. He had a broad repertoire, featuring a screwball, which he delivered from various arm angles while constantly changing speeds. “He’s the kind of pitcher you don’t want to face even once in a game,” said an opposing batter, Art Howe.1 One wonders whether such a hurler would have been allowed to develop in the U.S. — especially in today’s game, which emphasizes the radar gun, mechanics, and a repeatable delivery.

Romo learned the game in a different place, though — Mexico. After pitching professionally for 11 years in his homeland, he came to the major leagues in 1977 with an expansion club, the Seattle Mariners. The Pittsburgh Pirates obtained him in a trade after the 1978 season, and it was a good deal for them. When the Pirates won the World Series in 1979, one of their strengths was the bullpen. Romo was a key ingredient, appearing in 84 games, second most in the National League that year after teammate Kent Tekulve’s 94. In 1980 pitching coach Harvey Haddix said, “I think he was the unsung hero of last year’s team. The middle man seldom gets the credit he deserves because he doesn’t get wins or saves. But a good one keeps you in a lot of games, and Romo has done a tremendous job.”2

Actually, the 5-foot-11 righty won 10 games and saved five more in 1979, while losing just five and posting a 2.99 ERA. He had another good year with Pittsburgh in 1980, followed by two so-so seasons — and then his big-league career ended under a cloud in the spring of 1983. Decades later, Romo still refused to talk about this personal choice, and he had not taken part in any of the champion team’s reunions.

Enrique Romo Navarro was born on July 15, 1947, in Santa Rosalía, a port town in the state of Baja California del Sur. His parents were Santos “Santurria” Romo Urías, a policeman, and Rosario Navarro. Enrique was one of nine children in the family. He had four brothers (Vicente, Eusebio, José María, and Ramón) and four sisters (María Guadalupe, Lidia, Mirsa, and Olga).3

Vicente Romo, four years older than Enrique, was also a professional pitcher. He played more than 20 years in Mexico and the U.S., including eight seasons in the majors (1968-74; 1982) for five teams. Vicente’s nickname was “Huevo” (Egg) and so Enrique was sometimes called “Huevito.” In 1992 Vicente became a member of the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame. Enrique joined him in 2003, making them the first of just two pairs of brothers to be inducted there.4 In addition, José María, an outfielder, was good enough to play six seasons in the Mexican League (1979-84).

In 1952, when Enrique was about 5 years old, his family moved to the city of Guaymas, a short boat trip across the Sea of Cortez in the state of Sonora.5 The youth started to play baseball as an outfielder with a Mexican Little League team at the age of 12.6 Starting when he was 16, he served a three-year tour of duty in the Mexican Navy. “If I didn’t play baseball, I would still be in the Navy,” he said in 1980. “But as a boy I always watched the baseball players. I wanted to be one, and my older brother Vicente did well.”7

In 1966, 18-year-old Enrique became a professional ballplayer. He joined Puerto México of the Mexican Southeast League, a Class A circuit. He also switched to pitching at that time, strongly influenced by Vicente.8 In 22 games for the Porteños, he pitched 61 innings, winning one and losing two with a 3.10 ERA. Romo then gained his first experience in winter ball with the Guaymas Ostioneros of La Liga Sonora-Sinaloa (as the Mexican winter circuit was then known).

Back with Puerto México in the summer of 1967, Romo had marks of 4-5, 3.74, pitching 82 innings in 18 games. He made a great stride forward that winter, going 15-4 with a 1.53 ERA for Guaymas. That performance won him the Rookie of the Year Award, and the Oystermen became league champions.

In 1968 Romo stepped up to La Liga Mexicana de Béisbol, Mexico’s top summer league. He pitched there for nine seasons: four with the Jalisco Charros (1968-71), one with the Gómez Palacio Algodoneros, or Cotton Growers (1972), and four with the Mexico City Rojos (1973-76). Overall, he posted a won-lost record of 109-74, with a 2.67 ERA. He was mainly a starting pitcher, relieving 87 times in 292 total appearances. He threw 91 complete games, including 23 shutouts. He struck out 1,047 batters and walked 415 in 1,565 innings.

Romo also remained a standout in Mexican winter ball (that league became known as La Liga Mexicana del Pacífico, or Mexican Pacific League, with the 1970-71 season). Across 13 winter seasons, he won 96 and lost 64 for Guaymas, the Mazatlán Venados, and the Ciudad Obregón Yaquis.9 He pitched 1,346 innings in 243 games, striking out 844 and walking 381, and his ERA was 2.72. In the winter of 1974-75, Romo put up a 12-2 record for Ciudad Obregón, leading the LMP in winning percentage. He matched that feat the following winter, again going 12-2 for the Yaquis. In both seasons, he was named the LMP’s Pitcher of the Year.

Romo forged a lasting reputation among Mexican aficionados. One of the nation’s leading baseball historians, Jesús Alberto Rubio, expressed it in a sentence that would fit well on a plaque: “Feared by his opponents, respected by his colleagues, and admired by the fans who saw him pitch.” Romo was a member of three champion teams in the Mexican summer league, all with Mexico City (1973, 1974, and 1976). He added three more titles in winter ball. In addition to Guaymas (1967-68), they were Ciudad Obregón (1972-73) and the Navojoa Mayos (1978-79). He, as well as Pirates teammate-to-be Mike Easler, joined the Mayos as a playoff reinforcement in 1979. (This is a common practice during postseason play in winter ball.)

In addition, Romo played in three Caribbean Series, in which the region’s winter-ball champions square off in a round-robin tournament. Mexico was not part of the competition when it was revived in 1970, but joined the following year. In the 1973 edition, he helped Mexico gain its only victory against five losses, relieving his brother Vicente in the eighth inning. Al Hrabosky, then a St. Louis Cardinals farmhand, got the save. The following year, although Ciudad Obregón had finished in second place in the LMP, the Yaquis still went to the Caribbean Series (held in Mexico that year) as a replacement for the team from Venezuela, whose players were on strike. In 1979 Romo gave up a game-winning homer to Mitchell Page that decided the series in favor of Venezuela.

During the 1976 summer season with Mexico City, Romo took his game to a new level — 20-4, 1.89, with 239 strikeouts in 233 innings. The key to his increased success was a new weapon. “After I learned the screwball,” he said, “I didn’t have much trouble with left-handers. Before, I did.”10 It’s also most intriguing that Romo was an indirect influence on the star Mexican pitcher Fernando Valenzuela. The screwball was what made Valenzuela successful too, and he learned it from Bobby Castillo — who had picked up the pitch by watching Romo.11

Romo’s performance did not go unnoticed north of the Rio Grande. Lou Gorman, who had become general manager of the newly formed Seattle Mariners, was seeking to acquire talent by other means than the expansion draft. Gorman had contacts in the Mexican League and was friendly with Ángel Vázquez, owner of the Mexico City Reds. In 1974, when Gorman was with the Kansas City Royals, he had purchased the contract of Aurelio “Señor Smoke” López from the Reds. For the past few seasons, he had noted Romo’s performance with interest. He struck a deal with Vázquez for $75,000, far below the $175,000 Seattle had to pay for each player acquired in the expansion draft.12

Gorman envisaged Romo as either a starter or reliever for Seattle. When the 1977 season opened, Enrique was the number-two man in the rotation. He pitched well his first time out; in seven innings, he gave up just two runs on four hits, while striking out nine (which proved to be a big-league career high). That night at the Kingdome, however, Nolan Ryan fired a three-hit shutout for the California Angels. Thus, Romo took the loss. Five days later, he had another good outing. He left after seven innings with a 2-1 lead, but the bullpen couldn’t hold it. Romo’s third start, on April 17, was his last ever in the majors. He left after 1⅔ innings with a hamstring problem — something that had been bothering him since spring training — and went on the disabled list.13

Upon his return, Romo proved highly effective in relief. That July, Mariners manager Darrell Johnson said flatly, “Enrique Romo is the best reliever in the American League.”14 He finished with a club-high 16 saves in 55 bullpen outings, to go with an 8-10 won-lost record and 2.83 ERA. He struck out 105 in 114⅓ innings. Had Seattle been able to win more than 64 games that year, there would have been more saves.

With the Mariners in 1978, Romo did not have as good a year overall (11-7, 3.69, 10 saves in 56 games). “The ballclub was not good offensively and the defense was shaky,” he later said. “A pitcher doesn’t have a lot of confidence on the mound there.”15

That December Seattle traded Romo along with Rick Jones and Tom McMillan to Pittsburgh in exchange for Odell Jones, Mario Mendoza, and Rafael Vásquez. Rick Jones, a lefty pitcher, never appeared in another big-league game, though he was called up in September 1979. Neither did McMillan, a shortstop. Nonetheless, Romo alone made the trade turn out well for the Pirates. Right-hander Odell Jones was a talented pitcher but didn’t do much at the top level, though he appeared as late as 1988. Though Mendoza was a good-fielding shortstop, his infamously weak batting gave rise to the term “The Mendoza Line.”

Pittsburgh had to sweeten the pot with Vásquez to get the deal done. At the time Pirates general manager Pete Peterson said, “We recognize that Vásquez is an outstanding prospect.”16 As it developed, though, the Dominican (just 20 at the time of the trade) pitched just nine games for the Mariners in 1979 and never made it back to the majors. Peterson continued, “We’re thinking of next year and Romo fits into our plans.” Chuck Tanner added, “Our top priority in trades was a quality pitcher. We have accomplished our objective.” Tanner also wanted to provide support for Kent Tekulve, who had pitched 135⅓ innings in 91 games in 1978.17

“The trade surprised me,” said Romo in February 1979, while at the Pirates training camp in Florida. “I didn’t think Seattle would trade me. But I was happy to come here. I am glad to be with a team that can win it all.” That accurate prediction was issued in Spanish; Romo’s English was limited, and Manny Sanguillen served as his interpreter.18

Superscout Howie Haak observed, “With a screwball pitcher like Romo on our team, getting [another] left-hander is not as important. Sure we’d still like to have two left-handers and two right-handers [in the bullpen], but it’s not a big thing anymore.”19 As it developed, though, Pittsburgh did address this need in June by obtaining Dave Roberts from San Francisco to support Grant Jackson.

In an April interview, Romo was prophetic again. He said, “We have a good team but there are a lot of tough teams in our division. The season has a long way to go and we may have to go down to the last days of the race to decide the winner.” He also thought that from what he had seen to that point, the caliber of play was higher in the National League — “the thing I especially notice is that the batters as a whole are much more difficult to get out.” Several other interpreters were on hand for that talk, including teammates Rennie Stennett and Frank Taveras. (The latter was soon to be traded.)20

Romo got off to a shaky start with Pittsburgh in 1979. “I think he prefers warmer weather,” said Harvey Haddix that June. “I think he had trouble with the colder weather we had. He’s getting the feel of things over here. He’s with a new team, in a new league. It’s all strange for him. I think it takes a guy like him extra time.” Chuck Tanner agreed. “I think Romo wanted to do so well, he tried too hard,” said the skipper. He’s settled down and is a better pitcher now.” 21

Tanner also emphasized the importance of Romo’s role. “With the injuries we’ve had, the middle job is important to us. Very often we have to pull a starter early because we don’t want him to aggravate an injury.”22 Yet it’s noteworthy that Romo also finished 25 games in 1979.

That August Romo confirmed that he’d had to adjust to the NL hitters and that the cold early-season weather had bothered him. “I’m pitching some of the best ball of my career now,” he said. The main thrust of that interview, though, was his unhappiness in Pittsburgh and the U.S. in general. In addition to the language barrier, he thought that the Pirates fans were more demanding than those in Seattle — “Here, they expect me to be good every time out.” It also emerged that he thought Seattle had been disloyal by trading him, the best pitcher the Mariners had — he saw favoritism toward Americans.23

Through Rennie Stennett, Romo said that he would play five years total in the majors, then go home to his cattle and pig ranch in Mexico. Money was one reason to be in El Norte — but national pride was another. “I wanted to prove people wrong,” he said. “They think all Mexicans are bad, that they cause discipline problems or something like that. They always think of Mexicans as gangsters, as bandits.” Yet he had to laugh when his teammates — posing as “The Enrique Romo Fan Club” — presented him with a portrait of Pancho Villa.24 The picture came to adorn the clubhouse wall.25

One risks perpetuating Latino stereotypes, but Romo was a mercurial sort, as teammate Phil Garner told columnist Joe Starkey in 2011. Chuck Tanner had to be both tender and tough in handling the reliever. The skipper offered hugs of consolation on plane trips to California when a sobbing Romo couldn’t visit Mexico because his wife had taken away his green card. Tanner also lifted Romo off the ground by the throat when the pitcher once pulled a knife in the clubhouse, warning him not to do it ever again.26

Romo did not play a major role in the 1979 postseason. He appeared twice in the National League Championship Series against Cincinnati. In Game One at Riverfront Stadium, with the score tied at 2-2 in the eighth inning, he put two runners on; Tekulve then entered and induced a double play. The next day, Romo again came on in the eighth, replacing Grant Jackson with one out and nobody on. He gave up two straight hits; once more Tekulve got him off the hook and held the 2-1 lead (though he blew the save in the ninth).

Jackson, who knew Spanish from winter ball, thought nerves were a factor in the playoffs. He chatted with Romo to settle him down and said, “He’ll be OK in the [World] Series.”27 Romo was used just twice against Baltimore, though. In the sleety Game One at Memorial Stadium, with the Pirates trailing 5-1, he pitched a scoreless fifth inning despite walking two. In Game Three at Three Rivers Stadium, he replaced starter John Candelaria in the fourth inning after Kiko Garcia had cleared the bases with a triple. Romo proceeded to hit a batter and give up a single, enabling the Orioles to score two more runs and extend their lead to 7-3. He stayed in for 2⅔ more innings after that, allowing one more run on four hits.

Ahead of Game Seven, the Pittsburgh press indicated that Romo’s arm was bothering him.28 That may explain why he did not appear in the last four games of the Series. The dreadful baseball weather in Baltimore and Pittsburgh that October was also not to his liking. “I never felt the cold like I did in the World Series,” he said the following April.29

Back in Mexico over the winter of 1979-80, Romo (who had previously cut back to playing just part of the LMP season) played first base in a recreational league once a week. He joked, “I hit .700, but I’m not after Willie Stargell’s job.” He also dropped 15 pounds through dedicated exercise, getting down to 185. In March 1980 he said, “I’m prepared for the cold this year. I know what to expect and I’m not going to let it bother me. I’m just looking forward to the season.”30 He appeared in 74 games that year, pitching 123⅔ innings and posting a 5-5 record with a 3.27 ERA and 11 saves.

Romo also felt more at ease in the clubhouse. Grant Jackson said, “He didn’t know what to think about us last year. He didn’t know if we were fooling around with him or not. Now, he does.” Manny Sanguillen added, “He couldn’t believe how crazy we are. Now, he’s one of the biggest crazies here. He fits in.”31

That September Harvey Haddix described Romo’s repertoire and deliveries well. “He’s got a couple of different screwballs, a curveball and a fastball. He changes speed on all of them. He has a little slider. He throws side-arm, three-quarters and overhand.” Art Howe, then with the Houston Astros, also viewed Romo’s fastball as underrated. “You’ve got to be thinking fastball and adjust to the speed of the ball. … Some guys think he doesn’t throw hard, but he can move it up there on you pretty good.”32 Over the years, rumors also persisted that Romo employed a spitball or greaseball.

The same month, Chuck Tanner pointed to another of Romo’s skills. On September 10 at Busch Stadium in St. Louis, the pitcher helped himself after walking the leadoff man in the ninth inning, pouncing on a sacrifice bunt and getting the force at second. “He’s the best fielding pitcher in the league,” said Tanner. “He’s quick as a cat. You can’t teach things like that.”33

Romo was an all-around player. He had 10 hits in 37 at-bats in the majors (.270). His best moment with the bat came a few weeks after Tanner singled out his fielding. On October 1 at Shea Stadium in New York, he hit a grand slam in the eighth inning off reliever Roy Lee Jackson.

Early in the 1981 season, Romo talked about working on something else that had bothered him from time to time: beefs with umpires. This arose in the ninth inning against Montreal as he struggled to complete a difficult three-inning save. “I went out there and calmed him down,” said catcher Steve Nicosia. “I told him, ‘Hey, that’s over. The umpire missed a couple, but let’s go on to the next pitch.’ When Romo gets huffin’ and puffin’ out there, he’s losing his concentration.”34

Romo — who looked increasingly piratical, with a beard and longer hair — pitched in 33 games in 1981. He was 1-3 with a 4.54 ERA, though he did pick up nine saves. After the players strike ended in August, though, he appeared just nine times. He went on the 21-day disabled list in late August and returned for five appearances during the last two weeks of the season.

In spring training 1982, John Candelaria, Don Robinson, and Jim Bibby all had arm problems. Thus, Tanner thought about making Romo a starter once again, as he had also considered at one point in 1980. Enrique responded, “I’m ready. Baseball is baseball. You pitch two or three innings or you pitch nine innings. Either way, you still have to get them out.”35 It didn’t happen then because Pittsburgh acquired Ross Baumgarten from the Chicago White Sox, but Tanner again mulled giving Romo a start in late May after pulling Eddie Solomon out of the rotation.

In the end, though, Romo stayed in the bullpen, pitching in 45 games. He won nine and lost three, but his ERA was 4.36 and he had just one save. Toward the end of the season, Tanner gave him a stiff fine — $5,000 and two days’ pay (roughly $5,000 more) — for “breaking training.”36

After the 1982 season ended, Romo never wore a big-league uniform again. He did not report to spring training; according to his agent, Seymour Goldstein, Romo “brooded all winter” because of the fine.37 The pitcher didn’t get sympathy from his teammates, though. Captain Bill Madlock said, “When you don’t show up for a game, you should be fined, especially for anything that hurts your teammates.” Kent Tekulve, the team’s player representative to the union, added, “You have to have a fine. Docking a guy two days pay isn’t enough. Heck, I could take my family on vacation in the middle of September if all it would cost me was two days’ pay.”38

Chuck Tanner — one of the most sympathetic leaders in baseball history — was fed up and didn’t want Romo back. The Pirates tried unsuccessfully to trade their disgruntled reliever; meanwhile, starting on March 6 they began to fine him $500 a day. On March 16 the Pittsburgh Press reached Romo’s wife, Ruth, at their home in the city of Torreón. She said that he was in training “in another city, not too far away.” Seymour Goldstein, who’d been optimistic earlier that it would all work out, said, “I’ve washed my hands of the whole thing.”39

Finally, toward the end of March, Pete Peterson received a telegram from Romo informing him that the pitcher had retired.40 The team was thus able to put him on the voluntary retirement list; otherwise, he’d have had to go on the restricted list. If that had happened, Romo — who still had two years left on his contract, worth $700,000 — could still have shown up and claimed a roster spot. As his wife said, though, “Enrique doesn’t want to play for the Pirates any more. I don’t think he will come back unless maybe next year he changes his mind.”41

That never happened. There was talk that Romo was playing in an “outlaw” league at home; that was La Liga Nacional, which was started in 1981 by ANABE (Asociación Nacional de Beisbolistas), a Mexican players association. This circuit — founded in the wake of a strike — was better described by Jesús Rubio as “a great social movement.” It faced strong opposition from the entrenched Liga Mexicana and folded during the 1986 season.42 Romo was with the club called Tuzos de Zacatecas.43 If ANABE’s records still exist, they would be extremely difficult to find.

The most that Romo ever appears to have opened up about the mystery of his big-league retirement — and that’s very little — was in a Mexican interview from 2007. He said, “It’s something that I’m never going to tell anyone. I’ve been asked that many times, why, when I was of sound mind at age 35. But I never had a problem with anyone in the United States. I believe I could have played another four years because I was sound, I did good work and I never hurt my arm, but it’s something I keep to myself. It’s something that I decided, and at times I reproach myself, but I don’t regret it because I am well with my family.”44 He and Ruth (maiden name Ortiz) had two children, a daughter named Mary Gladys and a son who was also named Enrique.

The remark about not having any problems in the U.S. is interesting in view of an unconfirmed allegation in the book When the Bucs Won It All. Authors Bill Ranier and David Finoli wrote, “There was a story that Romo had been having a relationship with a woman who was involved with a mob figure and was told not to return to Pittsburgh.”45 It’s most unlikely, however, that this rumor could ever be verified.

When the Mexican Baseball Hall of Fame inducted Romo in 2003, he was visibly moved and delighted. He said, “I feel satisfied to have played six seasons in the major leagues, I made my best effort, and I believe that I represented Mexico well.” At that time, Romo held a job in a lathe workshop in Torreón.46

In November 2010 the Ciudad Obregón Yaquis bestowed a unique honor on Vicente and Enrique Romo, retiring their uniform numbers simultaneously. The occasion had another twist — receiving Enrique’s ceremonial pitch was his countryman Mario Mendoza Jr., whose father had been part of the trade that brought Romo to the Pirates. Mendoza Jr., who had also worn number 11 with the Yaquis, took the shirt off his back and gave it to Romo.

In his mid-60s, Enrique Romo remained active in baseball. In September 2012, he joined the “Super Master” team representing Laguna, the region that surrounds Torreón and its twin city Gómez Palacio. They played in the Independence Cup competition in Jalapa, in the state of Veracruz. Laguna won, with good pitching from Romo in the first game.47 In December 2013 he traveled from Torreón to Guaymas to face Vicente in a “Legends of Baseball” game, which featured an active major leaguer in Luis Ayala and at least one other MLB vet, Sid Monge. Enrique’s side won, 13-9, and he got credit for the victory. He had won all five matchups against Vicente during their professional careers, and before the game, he had joked, “I see it being difficult for him to beat me, if he could not at his best!” 48

Continued thanks to Jesús Alberto Rubio in Mexico.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted the following:

Books

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, editor. Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V.: 11th edition), 2011.

Internet resources

baseball-reference.com.

retrosheet.org.

salondelafama.com.mx/.

comc.com.

youtube.com.

Notes

1 Dan Donovan, “Unsung Romo’s Saving Grace Guns Down Houston,” Pittsburgh Press, September 4, 1980, C-1.

2 Donovan, “Unsung Romo’s Saving Grace Guns Down Houston.”

3 Gilberto Castro Meza, “Rinden merecido homenaje con una placa al Huevo Romo,” El Sudcaliforniano (La Paz, Baja California del Sur, Mexico), December 20, 2010. Gilberto Castro Meza, “Montarán una plaza alusiva en la casa donde nació ‘Huevo’ Romo,” El Sudcaliforniano, October 27, 2009.

4 The other, as of 2016, is Aurelio Rodríguez and his older brother Juan Francisco.

5 Yesenia Torrecillas, “Vicente ‘Huevo’ Romo: El Cy Young Mexicano,” Pelotapimienta.mx, March 6, 2014 (pelotapimienta.mx/vicente-huevo-romo-el-cy-young-mexicano).

6 Fred Sigler, “Trade Break for Romo,” Observer-Reporter (Washington, Pennsylvania), April 17, 1979, C-1.

7 Jack Gurnet, “Cards Stun Pirates 8-2,” Sarasota Herald-Tribune, March 30, 1980, 1-C, 6-C.

8 Sigler.

9 Romo’s Mexican Hall of Fame web page states that he also played for the Hermosillo Naranjeros in the LMP, but this has not been possible to verify. Detailed LMP records are hard to come by. As nearly as can be determined, Romo played for Guaymas from 1966-67 through 1968-69, for Mazatlán from 1969-70 through 1971-72, and for Ciudad Obregón from 1972-73 through 1978-1979.

10 Dan Donovan, “Romo May Solve Bucs’ Lefty Reliever Problem,” Pittsburgh Press, February 27, 1979, C-4.

11 Steve Wulf, “No Hideaway for Fernando,” Sports Illustrated, March 23, 1981; Dan Donovan, “Did Bucs Wake Up on Wrong Side of Season?”, Pittsburgh Press, June 11, 1981, C-1; Moisés Ramiro Segundo, “El artista del screwball,” El Universal (Mexico City), January 7, 2003.

12 Lou Gorman, High and Inside: My Life in the Front Offices of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2008), 153-154. Donovan, “Romo May Solve Bucs’ Lefty Reliever Problem”.

13 Raymond L. Andrews, “Johnson spells relief R-O-M-O,” United Press International, May 24, 1977.

14 Hy Zimmerman, “Who’s Finest A.L. Fireman? ‘Romo!’ the Mariners Shout,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1977, 16.

15 Donovan, “Romo May Solve Bucs’ Lefty Reliever Problem.”

16 Charley Feeney, “Bucs Take a Romo for Extra Relief,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1978, 46.

17 Feeney.

18 Donovan, “Romo May Solve Bucs’ Lefty Reliever Problem”

19 Ibid.

20 Sigler.

21 Dan Donovan, “Man of Many Motions Delivers As Pirate Reliever,” Pittsburgh Press, June 8, 1979, B-7.

22 Ibid.

23 Ron Cook, “Romo Can’t Wait to Leave,” Beaver County (Pennsylvania) Times, August 17, 1979, B-2.

24 Ibid.

25 “Pirate Profiles: Enrique Romo,” Pittsburgh Press, April 2, 1980, F-3.

26 Joe Starkey, “Tanner perfect for ’79 Bucs,” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, February 13, 2011.

27 Chraley Feeney, “Pirates Tap Kison For Series Opener Against Flanagan,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 8, 1979, 14.

28 Phil Musick, “Tekulve Sinkerball Could Be Key in Big Shootout,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, October 17, 1979, 20.

29 Dan Donovan, “Romo Turns Cold Shoulder To Spring Temperatures Here,” Pittsburgh Press, April 2, 1980, A-6.

30 Ron Cook, “Fans will see a lot less of slimmed-down Romo,” Beaver County Times, March 19, 1980, C-2.

31 Cook, “Fans will see a lot less of slimmed-down Romo”

32 Donovan, “Unsung Romo’s Saving Grace Guns Down Houston”

33 “Romo provides Pirate relief,” Associated Press, September 11, 1980.

34 Dan Donovan, “Romo Pops Montreal, Saves Win,” Pittsburgh Press, April 13, 1981, B-3.

35 Ron Cook, “Enrique Romo may start,” Beaver County Times, March 18, 1982, B4.

36 Russ Franke, “Tanner: Don’t Want Romo,” Pittsburgh Press, March 8, 1983, C-1.

37 Franke, “Tanner: Don’t Want Romo”

38 Russ Franke, “Berra’s New Attitude A Buc Bonus,” Pittsburgh Press, March 5, 1983, A-10.

39 “Romo won’t be back—wife,” Associated Press, March 17, 1983. “Extra Innings,” Pirates Gold (monthly magazine published by the Pittsburgh Pirates), April 1983.

40 John Barker, “Last Word in Sports,” Observer-Reporter, March 26, 1983, B-8.

41 Franke, “Tanner: Don’t Want Romo”. “Romo won’t be back—wife”. Ron Cook, “Buc Bits,” Beaver County Times, March 27, 1983, C8.

42 For further information on ANABE and this league, see David G. LaFrance, “Labor, the State, and Professional Baseball in Mexico in the 1980s,” which forms Chapter 6 of Joseph L. Arbena and David G. LaFrance, editors Sport in Latin America and the Caribbean (Wilmington, Delaware: Scholarly Resources Inc., 2002).

43 “Calientan el ambiente ex-Tuzos de Zacatecas,” Imagen de Azacatecas (Guadalupe, Zacatecas, Mexico), August 21, 2004.

44 Jorge Carlos Menéndez Torre, “‘El Huevito’ Romo, un ex Ligamayorista que ahora vive de la tornería,” Poresto.net, January 1, 2007 (http://www.poresto.net/ver_nota.php?zona=yucatan&idSeccion=19&idTitulo=138860)

45 Bill Ranier and David Finoli, When the Bucs Won It All: The 1979 World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005), 155.

46 Claudio Martínez Silva, “Salón de la Fama del Beisbol, a 30 años,” El Siglo de Torreón, August 21, 2003.

47 Sergio Luis Rosas, “Ex ligamayorista reforzará a Selección Laguna Master,” El Siglo de Torreón, September 12, 2012. “Laguna conquista la Copa Independencia,” El Siglo de Torreón, September 19, 2012.

48 Jorge Castillo Morán, “Vivirá Guaymas histórico y fraternal duelo de béisbol,” El Vigia (Guaymas, Sonora, Mexico), December 4, 2013. Game account with photos, Deportivas regionales de Jorge Castillo Morán, the journalist’s Facebook page, December 16, 2013.

Full Name

Enrique Romo Navarro

Born

July 15, 1947 at Santa Rosalia, Baja California Sur (Mexico)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.