Oscar Charleston

“Charleston not only has the speed of a Carey, the arm of a Meusel, the brains of a McGraw and the hitting ability of a Hornsby, but he is a singer of rare ability, a writer of parts, a billiard player of more than ordinary skill and a happily married man. Charleston is a rare specimen of one upon whom the gods have smiled in affable mood. Oh, he’s a bird of a boy, is Oscar, and his personality – mysterious, inexplicable, indescribable, has won for him a warm spot in the hearts of each and every one of his players.”1

A scout for the St. Louis Cardinals, Bennie Borgmann, once said, “In my opinion, the greatest ballplayer I’ve ever seen was Oscar Charleston. When I say this, I’m not overlooking Ruth, Cobb, Gehrig, and all of them.”2 Buck O’Neil said that Charleston “was like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Tris Speaker rolled into one.”3 Honus Wagner said, “I’ve seen all the great players in the many years I’ve been around and have yet to see one any greater than Charleston.”4 And, in 2001, Bill James ranked Charleston as the fourth-best player of all time, behind only Ruth, Wagner, and Willie Mays.

A scout for the St. Louis Cardinals, Bennie Borgmann, once said, “In my opinion, the greatest ballplayer I’ve ever seen was Oscar Charleston. When I say this, I’m not overlooking Ruth, Cobb, Gehrig, and all of them.”2 Buck O’Neil said that Charleston “was like Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, and Tris Speaker rolled into one.”3 Honus Wagner said, “I’ve seen all the great players in the many years I’ve been around and have yet to see one any greater than Charleston.”4 And, in 2001, Bill James ranked Charleston as the fourth-best player of all time, behind only Ruth, Wagner, and Willie Mays.

Charleston was a baseball lifer who served as a player, manager, umpire, and scout. Though he worked an assortment of other jobs to supplement his income, baseball was his life. It was on the ball field that Charleston developed a reputation as a hothead and performed apocryphal deeds such as yanking the hood off a Ku Klux Klansman and throwing a professional wrestler off a train. Off the field, Charleston married twice but divorced one wife and separated from the other; he left behind no children. He neither drank nor smoked and was a stern yet charming man who gained the respect of his peers through his no-nonsense attitude.

Oscar McKinley Charleston was born in Indianapolis on October 14, 1896. He was the seventh of 11 children born to Tom and Mary (Thomas) Charleston. His middle name came about because his parents were Republicans, and William McKinley was the Republican nominee for president in 1896. Oscar’s father was a construction worker and, according to one report, a former jockey. As a child, Oscar moved constantly, but always to some place within the greater Indianapolis area. His family was poor, and Oscar finished school only through the eighth grade. During his childhood, Oscar allegedly worked as a batboy for the Indianapolis ABCs, the most prominent local Black team.5

Rather than continue in school, Charleston lied about his age so that he could enlist in the US Army at 15. Shortly thereafter, he was shipped out to the Philippines and assigned to Company B of the 24th Infantry Regiment. Playing for the regimental team, Charleston starred as a pitcher and was selected for an all-star game in which he pitched a one-hit shutout and hit a triple. When his hitch was over, he was honorably discharged in 1915.

Charleston, who was between 5-feet-8 inches and 5-feet-9 inches, returned stateside and began to play for the Indianapolis ABCs.6 He pitched a shutout in his first game, striking out nine, walking none, and giving up only three hits. He also displayed impressive hitting prowess throughout the season. At the conclusion of the 1915 season, the ABCs played a series of exhibition games against White teams composed of major leaguers. During one of these games – on October 24, 1915 – a scuffle broke out between an ABCs player and a White umpire. Amid the scuffle, Oscar Charleston ran in from center field and punched the umpire. The sight of a Black man punching a White man caused chaos, as players, fans, and police poured onto the field. Before there could be any trouble, Charleston ran away. He was later arrested but was released on bond and allowed to go to Cuba with the ABCs.7

After the incident, ABCs owner C.I. Taylor issued a statement apologizing for the actions of his hotheaded center fielder. Charleston also published a statement saying he could not control his temper and that “[he] cannot find words in the vocabulary that will express his regret.”8 After the 1915 season, Charleston played in Cuba with his ABCs teammates. But, perhaps still having trouble controlling his temper, he was at one point dismissed from the team for disobeying club rules.9

Charleston played the first part of the 1916 season for the Lincoln Stars in New York before returning to the ABCs in August. In October the ABCs played Rube Foster’s American Giants in a seven-game series billed as Black baseball’s championship. The ABCs won the series, with Charleston going 7-for-18. During the offseason, he worked as a grocery clerk.

On January 9, 1917, Charleston married Hazel M. Grubbs, a young woman in her late teens who was the daughter of a public-school principal. Their marriage did not last long and, by early 1918, the couple had separated; they were divorced in 1921.

Charleston continued playing for the ABCs in 1917. As the United States became involved in World War I, Charleston registered for the draft on June 5, 1917; in order to maintain consistency with his previous lie, he listed his birth date as October 14, 1893.10 The ABCs posted a sub-.500 record against elite opponents this season, but Charleston continued his ascent. In games against elite opponents, Charleston posted a batting line 50 percent above league average.11 Because he was registered for the draft, he was unable to play in Cuba during the offseason.

Charleston continued his strong play in 1918. In a game on August 18, he made what was described as one of the greatest catches ever at Washington Park.12 In the field, Charleston’s incredible speed (he clocked in at 23 seconds in the 220-yard dash with the Army) allowed him to play shallow, just behind second base.13 Later in August Charleston was assigned to Camp Dodge in Johnston, Iowa, and was selected to attend the Colored Students Infantry Officers Training School in Arkansas. The war ended before he could become an officer and, on December 3, he was again honorably discharged.

Charleston emerged as a star in the postwar years. In 1919 he played for Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants and started the year in center field. Charleston showed his talents at bat, in the field, and on the bases. In the majors in 1919, Babe Ruth hit one home run every 19 plate appearances, while Charleston hit one home run every 26 plate appearances.14 Charleston’s defense was frequently written about, with the press describing him as making “hair-raising [catches]” and the “fielding feature[s] of the game.”15 Charleston was also a superb baserunner, and Foster pushed Charleston on the basepaths. In one game, Charleston had what was described as one of the speediest exhibitions of running ever seen on the diamond when he hit a single, stole second, advanced to third as the ball trickled into center field, and came home on a throw down to second.16 At the season’s conclusion, the Chicago Defender wrote that Charleston was the best player in the world, even better than Ty Cobb.17 The paper further credited Foster for developing Charleston’s natural abilities and cooling his temper.18 In fact, Charleston seemed preoccupied with the comparison to Cobb, repeatedly clipping articles for his personal scrapbook that compared him to the Georgia Peach. When the season ended, Oscar took a job as a chauffeur.19

With the creation of the Negro National League in 1920, Charleston re-signed with the ABCs, a move Foster allowed in the interest of league-wide competitive balance.20 His 1920 season was another star turn as he stole 20 bases and posted an OPS that was 76 percent better than the league average. In the inaugural NNL doubleheader, Charleston went 1-for-4 in the first game and laced a two-run triple in the second game.21 The press also continued to make note of his defensive ability. In a game one week later, the ABCs were leading 4-2 in the top of the ninth with two men on and two men out when José Leblanc hit a rocket to center field. Charleston, who had already made two good catches, saved the game with a dazzling catch made with his back to the plate. The fans jumped onto the field and showered Charleston with money.22

Now in demand, Charleston was sold to the St. Louis Giants for the 1921 season. He took pride in his purchase price, clipping a newspaper article that stated he was worth more than Rogers Hornsby or Babe Ruth.23 He had another strong campaign during which he led the Negro National League in home runs, hitting 15 in 339 plate appearances.24 In fact, there were three occasions during the season on which Charleston hit two home runs in one game. Because of his surge in power, newspapers started to call him the colored Babe Ruth; this is the major-league player to whom Charleston was most frequently compared during the 1920s.25 Charleston also stole 32 bases and hit .433. After the 1921 season, Charleston spent the winter in Los Angeles and played in the California Winter League. He hit .405 as the Colored All-Stars went 25-15-1 and posted a winning record in games against teams that included both major- and minor-league players. By the end of the California Winter League season, the Los Angeles press proclaimed Charleston to be the second greatest living player, behind only Babe Ruth.26

In 1922, thanks to St. Louis’s financial difficulties, Charleston once again returned to the ABCs.27 C.I. Taylor had died between the 1921 and the 1922 seasons, and ownership of the ABCs transferred to his wife, Olivia. (Charleston later spoke very positively of Taylor, crediting him with teaching him how to manage a team.)28 In 1922 the ABCs were led by three outstanding hitters – Biz Mackey, Ben Taylor, and Charleston. In the league’s opening doubleheader, Charleston went 6-for-8 with a home run and a double. That set the tone for his season: Of the 98 games for which box scores exist, Charleston failed to get a hit in only 16. Bill James has rated Charleston as the best player in the Negro Leagues for the 1921 and 1922 seasons.29

After the 1922 season, Charleston married for the second time. The bride was a 27-year-old schoolteacher named Jane Howard. It was also Jane’s second marriage; her first husband had died in 1918. She often traveled with Charleston to Cuba during the winter, and several photos of them in Cuba appear in Charleston’s scrapbook. In fact, Charleston and Jane traveled to Cuba for their honeymoon, where Charleston played in the 1922-23 Cuban winter league.30 He and Jane had a rocky marriage, it seems, in part because Jane did not like baseball. It is possible that Oscar was unfaithful, too, as multiple contemporary newspaper articles reported that he was seen in public with women other than Jane.31 In fact, after a car accident in which Charleston escaped without injury, the Pittsburgh Courier wrote that Charleston “wiggled out of some love tangles the same, same way.”32 The couple separated in 1940, though they never divorced. Charleston filed for divorce in 1941, but the case was dismissed in 1942. Jane did not believe in divorce.33

In December 1922, Olivia Taylor traded Charleston to Rube Foster’s American Giants. Taylor was facing financial difficulties, and Biz Mackey and Ben Taylor also left the team. But Charleston returned to the ABCs prior to the season: Foster realized it was better for the league if Charleston played for the ABCs, and he worked out a deal with Taylor whereby Taylor would receive a subsidy for 1923 and let Charleston go to the American Giants in 1924.34 Charleston spent the 1923 season with the ABCs and was the leader of a depleted team that struggled to a fourth-place finish. In fact, the team needed Charleston to pitch on multiple occasions.

After the Indianapolis team disbanded, rather than heading to Chicago Charleston played for and managed the Harrisburg Giants, where he remained from 1924 to 1927. Charleston, who seemed to be preoccupied with the press coverage he received, clipped an article for his scrapbook that described him as a big loss for Foster’s league.35 In 1924 Charleston had another strong year at bat; though his team endured a .500 campaign, he reportedly hit 36 home runs by August 24. Charleston even had a stretch in early August where he hit seven home runs in three games.36 That October, the Harrisburg Giants played a postseason series against the crosstown (and White) Harrisburg Senators. There, in the middle of a competitive game, Charleston erupted when he attempted to punch an umpire after a bad call. The umpire evaded the punch, punched Charleston, and then ejected him from the game.37 Charleston returned to manage the Giants for the 1925 season. At age 28, he was in the prime of his career and had a magnificent season in which he batted .4271/.523/.776 with 20 home runs.38 Once again, Bill James has rated him as the best player in the Negro Leagues that season.39 From 1919 to 1925, Charleston posted an OPS+ above 200 four times and compiled a 1.143 OPS. Combined with his superb defense and great baserunning speed, this seven-year stretch ranks among the most dominant in baseball history.

After the 1925 regular season, Charleston played in an exhibition contest against a White “Bronx Giants” team that featured a young Lou Gehrig. Gehrig went 1-for-2 with two walks, while Charleston went 4-for-6 with a home run.40 During his career, we have box scores for 53 games in which Charleston played against major-league players, hitting .318 with 11 home runs. He got hits against Walter Johnson, Bob Feller, and Lefty Grove.41

In addition to his domestic play, Charleston burnished his reputation as a baseball star through his play in Cuba. He was known as “El Terror de los Clubs,” with one newspaper describing him as a man capable of fighting alone against other teams.42 During the time Charleston played in Cuba, it was a beisbol paradiso, as both major-league and Negro League stars spent their winters on the island. He had several superb seasons there and left quite an impression on Cuba’s baseball fans. In 1922–23, Charleston hit .446 in league games but was unable to qualify for the batting title when his Santa Clara team withdrew from the league because of a league decision that took away a win.43 In 1925 Charleston was part of a Cuban All-Star team that played against an All-Yankee team in front of Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.44 In 1926-27 Charleston was one of four players (along with Pablo “Champion” Mesa, Tank Carr, and Dick Lundy) to hit over .400.45 Over 996 at-bats in Cuba, Charleston hit. 361 with 19 home runs and 58 stolen bases.46 His team also won three championships.

The best team Charleston played on was the 1923-24 Leopardos de Santa Clara, a team whose reputation in Cuba is much like that of the 1927 Yankees in the United States. That team was so dominant that the other teams in the league decided to award Santa Clara the league title based solely on the first half of the season.47 The team had the best Cuban outfield ever, with Charleston, Champion Mesa, and Alejandro Oms giving Santa Clara outstanding offensive performances.48 During this season, Cuban newspapers referred to Charleston as the best player in the league and as a perfect star who combined intelligence, baserunning, slugging, fielding, and clutch play in a way never before seen. Charleston led the league in runs scored and stolen bases.49

The 1923-24 season also saw Charleston get into a famous fight with a Cuban soldier. The fight started on January 19 after Charleston spiked an opposing player as he slid into third base. The player’s brother, a soldier, came onto the field and charged Charleston, sparking other soldiers to come onto the field as well. The fight was broken up and Charleston’s scrapbook shows him standing peacefully next to a soldier.50 Charleston was initially criticized and mocked in the press, but he was defended by his friends, who described him as a perfect gentleman who had become involved in an unfortunate accident.51 Charleston met with the Cuban military and explained that he had only been acting in self-defense. The military accepted the explanation, and Charleston received no punishment.

Charleston played the 1928 and 1929 seasons with the Hilldale club of Darby, Pennsylvania. (Darby is a Philadelphia suburb.) As he embarked upon his age-31 season in 1928, Charleston appeared more rotund than in prior years, but his batting performance remained strong, and he posted a .348/.453/.618 line. For the first time, Charleston played first base in addition to the outfield. Hilldale added Martin Dihigo for the 1929 season, which gave the team a powerful duo and led one newspaper to call Hilldale “[the] greatest ball team.”52 The press’s praise for Charleston remained especially effusive, and he was referred to as being “without fault” and “as near perfect as ball players come.”53 However, the press has always been fickle, and when Hilldale got off to a slow start in 1929, a newspaper account claimed that Charleston was not performing up to his usual standards.54 He still ended up with a 152 OPS+ for the season. Charleston then joined the Homestead Grays for a fall barnstorming tour, after which he stayed in Philadelphia and worked as a baggage handler.55

Charleston must have enjoyed playing with the Homestead Grays because he joined the team for the 1930 and 1931 seasons. Charleston was a leader on the team and during preseason training in Hot Springs, he led the players on daily five-mile runs.56 This training helped Charleston slim down prior to the 1930 season. In the home opener, Charleston had three hits, including a home run and a triple.57 The Grays were buoyed by the addition of Josh Gibson and played the Lincoln Giants in a 10-game series to determine who would claim the 1930 championship. In the first contest, Charleston hit a two-run homer as the Grays won, 9-1. In the seventh game, Charleston injured his leg and as a result was unable to play in the series’ final game. The Grays still won, and Charleston had his second Negro League championship.

In 1931 Charleston, now playing first base regularly, drew rave reviews for his defensive ability as the Grays won a second consecutive championship with six Hall of Fame players on their roster: Charleston, Gibson, Jud Wilson, Smokey Joe Williams, Willie Foster, and Satchel Paige (though he played in only one game). Newspaper writers continued to praise Charleston, with one columnist asserting that he was a better player than Rogers Hornsby because Charleston not only had a great bat but also was a superb baserunner and exceptional fielder.58 Batting leadoff, Charleston had a good season. In a mid-July game against Hilldale, he hit a go-ahead two-run homer to give Homestead a 5-4 victory.59 In a September doubleheader against Kansas City, Charleston hit four doubles and a single in the first game and got two walks and a single in the nightcap.60

On January 28, 1932, Charleston was named player-manager of the Pittsburgh Crawfords after Gus Greenlee outbid Cumberland Posey, the Grays’ owner, for Charleston’s services. The 1932 Crawfords possessed some transcendent baseball talent, as Charleston helped recruit Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson to join the team.61 Even with so many talented players, Charleston remained the team’s main attraction.62 After the major-league season, the Crawfords played seven games against a team of major-leaguers and won five of the seven contests.

In 1933 the Crawfords added Cool Papa Bell and Judy Johnson, both future Hall of Famers, to the team. Charleston remained an extremely popular player, as was demonstrated by his leading vote total for the inaugural Negro League All-Star Game that year. He also remained extremely competitive: After an umpire made what Charleston deemed an incorrect call, he became so angry that he inserted himself as a relief pitcher and walked six straight men – his way of showing that he considered the game a farce.63

The following year, 1934, Charleston ranked as the Crawfords’ second-best hitter by OPS+ after Gibson, but the team failed to win either the first- or second-half title. Charleston often continued to be the Crawfords’ headliner, although Paige now challenged him for the title as he received more votes than Charleston for the 1934 All-Star Game. Nonetheless, for a game on June 10, the Washington Post gave Charleston top billing and referred to him as the highest paid Black player in the game.64 After the season, the Crawfords played a barnstorming White team that featured Paul and Dizzy Dean. In a game that Dizzy Dean pitched, Charleston singled in the only run Dean allowed the Craws.

Going into the 1935 season, Charleston expected his club to be a “hustling, wide-awake ball club and one of the best teams he ever had the privilege of managing.”65 Even though Satchel Paige did not return to the team, Charleston refused to lower his expectations for the 1935 season. He got off to a hot start, hitting a home run in the home opener to lead the Crawfords to a victory and hitting a home run at Greenlee Field that went over 500 feet.66 Charleston also remained a threat on the basepaths and even made a straight steal of home in a game on August 5.67 By early June, Charleston believed that his team was the cream of the crop.68 According to Jeremy Beer, the club posted a 24-6 first-half record but did not play as well in the second half. Charleston was still popular with the fans and won the All-Star Game voting for first base by one vote over Buck Leonard. At the end of the season, the Crawfords played the New York Cubans in the NNL Championship Series. Charleston hit two home runs in the series and managed the Crawfords to the 1935 championship in a thrilling seven-game series. At the end of the season, even Grays owner Cum Posey praised Charleston’s managerial ability, crediting him with a good managerial job in leading the Crawfords to the championship.69

In 1936 Satchel Paige rejoined the Crawfords, and Charleston was credited with “taming the temperamental” hurler.70 Manager Charleston put himself into a first-base platoon with a young player named Johnny Washington and batted himself fifth in the order. Now known as the “Old Maestro of Swat,” a well-rested Charleston remained a strong hitter and posted a 152 OPS+.71

As a business, the Crawfords struggled in 1936, leaving Greenlee short on funds as the team headed into the 1937 season. The team traded Josh Gibson and Judy Johnson to Homestead for Pepper Bassett, Henry Spearman, and $2,500. Greenlee was dismayed when Satchel Paige took a lucrative offer to play in the Dominican Republic, leading to the Crawfords losing nine additional members from their roster.72 Charleston managed a decimated team and sat himself regularly while he gave most of the playing time at first base to Johnny Washington. However, he remained capable of big moments, such as the one he had on Opening Day, when he won the game with a two-run homer in the eighth inning. It was a sign of the changing times and Charleston’s gradual decline that he failed to make the All-Star team, losing the first-base voting to Leonard that year. The Crawfords finished with a 21-38-1 final record, but Charleston’s reputation remained intact; in December, he was selected as the center fielder on Cum Posey’s all-time Negro League squad.73

The Crawfords did not fare much better in 1938. Although Charleston attempted to put together a quality team, the squad finished in fourth place. After the season Greenlee sold the Crawfords to Hank Rigney, who moved the team to Toledo, Ohio. The Crawfords lost many of their star players prior to the sale as Greenlee could no longer afford their salaries. Greenlee also sold Paige’s contract to the Newark Eagles for $5,000 in an attempt to make one last bit of profit from his franchise. Rigney kept Charleston as manager and part-time player for the Toledo Crawfords in 1939, but the team posted a sub-.500 record and switched leagues – from the NNL to the NAL – in midseason. By this time, Charleston’s playing days had effectively ended, though he still played in games on rare occasions. Yet his involvement with baseball continued, as he became the manager of the Philadelphia Stars in 1941 and played for and managed the semipro Quartermaster Depot team, where he worked, in Philadelphia in 1942 and 1943. At the ripe old baseball age of 46, Charleston still managed to garner a player-of-the-week award.

Soon thereafter, Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey sought Charleston’s help in identifying Black players who could play major-league baseball. In 1945 a new Black baseball circuit, the United States League, had been launched by Gus Greenlee. Rickey hired Charleston to manage the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers, the league entry that played at Ebbets Field. Charleston provided information on players that helped Rickey learn about their backgrounds and characters. One of the players Charleston advised Rickey about was future Hall of Fame catcher Roy Campanella, who played for the Baltimore Elite Giants at that time. The USL folded in its second season and, after his work for Rickey, Charleston was unable to find a managerial job, so he decided to become an umpire for the 1946 and 1947 seasons.

In 1948 Ed Bolden hired Charleston to manage the Philadelphia Stars.74 By this time, the Negro Leagues were losing their best players to Organized Baseball, thanks to the integration of the game that had been initiated by Rickey and Jackie Robinson. Charleston managed the Stars from 1948 through 1952, but the team never finished better than fourth. Still, he was reported to have done a great job with the team.75 In an era when Black baseball players had a reputation for rowdiness, Charleston’s team followed the straight and narrow path, earning themselves the nickname “the Saints.”76 Charleston had mellowed with age, and his players referred to him as being “relaxed,” “very mild,” and “friendly.”77

The Stars disbanded after the 1952 season, and Charleston was not involved in baseball in 1953. He returned to manage the barnstorming Indianapolis Clowns to an NAL championship in 1954. In October of that same year, Charleston fell down a flight of stairs at his home, an accident that left him paralyzed from the stomach down. Charleston initially thought he would recover, but he died due to the injury on October 5, 1954, at the age of 57. He left behind no spouse or children. Thousands of fans attended Charleston’s viewing in South Philadelphia.78

In the early 1970s, the National Baseball Hall of Fame formed a committee to remedy the lack of Negro League players in Cooperstown. Charleston was elected in 1976, following the elections of Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Monte Irvin, Cool Papa Bell, and Judy Johnson. Oscar’s sister Katherine delivered his induction speech, which she said was the greatest delight of her life.

Today, Oscar Charleston rests in an unadorned grave in Floral Park Cemetery in Indianapolis. His headstone consists of a simple gray slab – standard issue for United States military veterans. No mention is made of the great American athlete – considered by many the greatest Negro Leagues player of all time – who lies underneath.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Charleston’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, contemporary newspaper articles about Charleston, and his personal scrapbook.

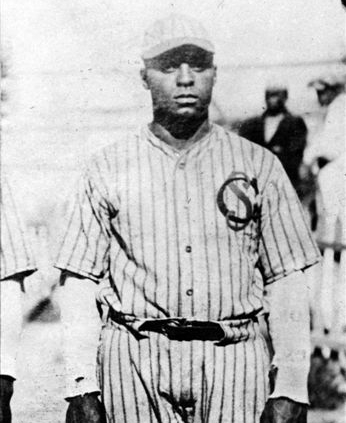

Photo credit: Oscar Charleston, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Notes

1 William G. Nunn, “Diamond Dope,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 20, 1925: 12.

2 Grant Brisbee, “Baseball Time Machine: 20 Individual Seasons Worth Going Back in Time For,” The Athletic, July 19, 2019.

3 Brisbee.

4 Jeremy Beer, Oscar Charleston: The Life and Legend of Baseball’s Greatest Forgotten Player (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 328.

5 Beer, 44. Charleston’s job as a batboy for the Indianapolis ABCs is typically included in his biography, though no definitive proof exists to show this is true.

6 In the Hall of Fame press release announcing his induction, Charleston’s height and weight are listed as 5-feet-11 and 210 pounds. But on his World War II draft card, Charleston listed his height as 5-feet-8.

7 My account of this game is taken from “Race Riot Is Balked by Police,” Indianapolis Star, October 25, 1915.

8 “Charleston’s Unclean Act – He Is Very Sorry,” Indianapolis Freedman, November 13, 1915.

9 “Charleston Dropped by the A.B.C. Club,” Indianapolis Star, November 26, 1915.

10 Oscar Charleston, 1917 Draft Card Registration.

11 Beer, 89.

12 “A.B.C.’s wallop New York Red Caps,” Chicago Defender, August 24, 1918.

13 “Oscar McKinley Charleston,” in David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000).

14 Beer, 110.

15 Beer, 109.

16 Beer, 109.

17 “Oscar Charleston, Giants’ Crack Center Fielder,” Chicago Defender, in Oscar Charleston’s Personal Scrapbook, available at the Negro Leagues Museum in Kansas City.

18 “Oscar Charleston, Giants’ Crack Center Fielder.”

19 Beer, 111.

20 Beer, 116.

21 Beer, 117-18.

22 “Great Playing Beats Cubans,” Indianapolis Star, May 10, 1920.

23 “How Much for This One?” in Oscar Charleston’s pPersonal Scrapbook.

24 Beer, 124. This figure differs from the data on Seamheads, which is 17 in 362 PAs.

25 Beer, 124.

26 Beer, 130.

27 Beer, 132.

28 Beer, 132.

29 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 175.

30 Beer, 145.

31 Beer, 272-73.

32 “Talk ’O Town,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 12, 1938.

33 Beer, 274.

34 Beer, 149.

35 “Migration Hits Foster League,” in Oscar Charleston’s Personal Scrapbook.

36 Beer, 160-61.

37 Beer, 163.

38 When sources differ on statistics, SABR uses the statistics from Seamheads.com.

39 James.

40 William E. Clark, “Little World Series for Bronx Title,” New York Age, October 24, 1925.

41 Phil Richards, “Retro Indy: Oscar Charleston,” Indianapolis Star, February 28, 2011, available in Charleston’s Hall of Fame player file.

42 “El Terror de los Clubs,” in Oscar Charleston’s Personal Scrapbook.

43 Jorge Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 143.

44 Figueredo, 162.

45 Figueredo, 171.

46 Oscar Charleston record in Cuba, available in Charleston’s Hall of Fame player file.

47 Harrisburg Courier, February 3, 1924.

48 Figueredo, 150.

49 Figueredo, 149

50 Beer, 155.

51 Beer, 155.

52 W. Rollo Wilson, “Hilldale Is Greatest Ball Team: Aggregation Credit to National Pastime,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 16, 1929.

53 Wilson.

54 “Cuban Stars Twice Wallop Hilldale,” Baltimore Afro-American, June 15, 1929.

55 “Johnson, Charleston, Stevens, Thomas play for Posey,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 19, 1929.

56 Beer, 206.

57 Beer, 209.

58 C.E. Pendleton, “Charleston’s Fielding Makes Him Greater Than Hornsby, Opinion,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 30, 1931.

59 “Homestead Grays Defeat Hilldale 5 to 4, and Takes [sic] Lead in the Series,” New York Age, July 18, 1931.

60 “Has Big Day,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 5, 1931.

61 Beer, 229.

62 Beer, 230-31.

63 Beer, 237.

64 “Negro Nines Clash at Stadium Today,” Washington Post, June 10, 1934.

65 Chester L. Washington, “Sez ’Ches,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 11, 1935.

66 Al Abrams, “Sidelights on Sports,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 29, 1935: 20.

67 “Chester Loses,” Delaware County Times (Chester, Pennsylvania), August 6, 1935.

68 “Crawford Out to Win from Farmer Nine,” Times Union (Brooklyn, New York), June 6, 1935: 14.

69 “Cum Posey’s Pointed Paragraphs,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 21, 1935: 13.

70 Beer, 257.

71 “Adding Color to Baseball,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 7, 1936.

72 “Players Who Fled League Face Return/Morton Files Names with Government for Damages,” New York Amsterdam News, May 29, 1937: 17. The list of players submitted to the State Department on May 24 included Pittsburgh Crawfords players Leroy Matlock, Ernest Carter, Chet Brewer, Satchel Paige, Bill Perkins, Cool Papa Bell, Thad Christopher, Sam Bankhead, Harry Williams, and Pat Patterson.

73 “Meet Cum’s All-Time All-Americans,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 18, 1937. The final record of the team is as presented by Beer.

74 “Phila. Stars to Begin Spring Training April 1,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 27, 1948.

75 “Bushwicks Host to Philly Stars at Dexter Tonight,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 16, 1948.

76 Richards.

77 Beer, 21.

78 Beer, 327.

Full Name

Oscar McKinley Charleston

Born

October 14, 1896 at Indianapolis, IN (US)

Died

October 5, 1954 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.