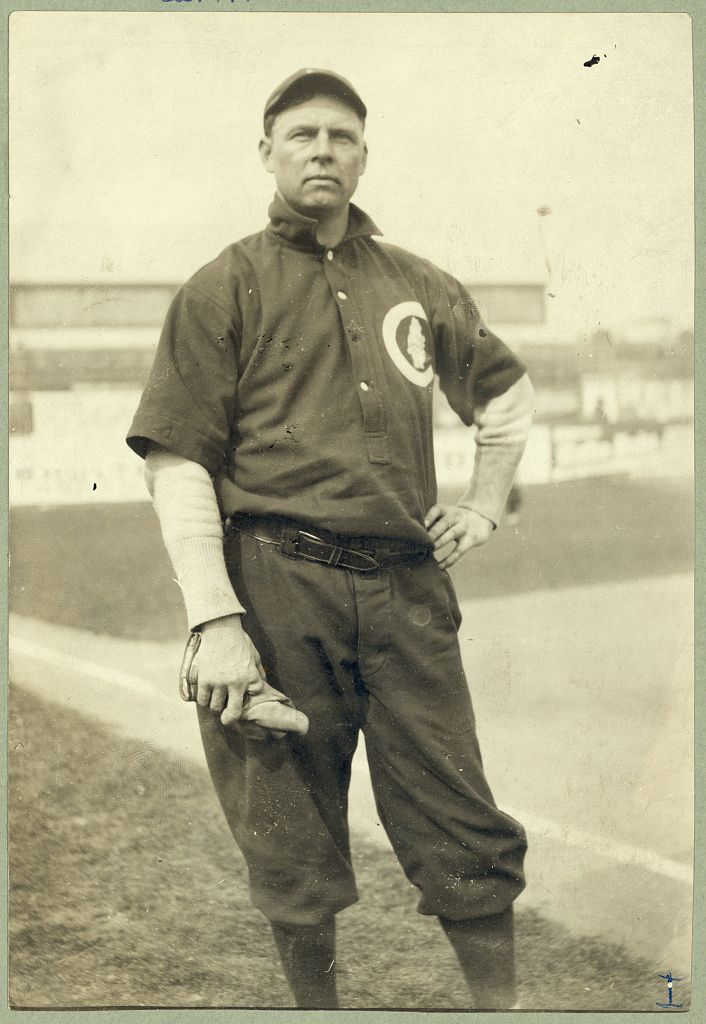

Mordecai Brown

Mordecai Peter Centennial Brown, best known today for his unusual name and his more or less descriptive nickname of “Three Finger,” was the ace right-hander of the great Chicago Cub teams of the first decade or so of the Twentieth Century. With Brown leading an extraordinary pitching staff, the Cubs from 1906 through 1910 put together the greatest five-year record of any team in baseball history. His battles with the Giants’ Christy Mathewson epitomized the bitter rivalry between two teams that just about matched each other man for man.

Mordecai Peter Centennial Brown, best known today for his unusual name and his more or less descriptive nickname of “Three Finger,” was the ace right-hander of the great Chicago Cub teams of the first decade or so of the Twentieth Century. With Brown leading an extraordinary pitching staff, the Cubs from 1906 through 1910 put together the greatest five-year record of any team in baseball history. His battles with the Giants’ Christy Mathewson epitomized the bitter rivalry between two teams that just about matched each other man for man.

Brown was born October 19, 1876, in the farming community of Nyesville, Indiana, to Jane (also known as Louisa) and Peter Brown.

Because the year of his birth was our country’s centennial, Mordecai was given an extra middle name. Although it is generally assumed that the quite religious Browns chose their son’s names from the Bible, Peter was his father’s name, and there was an uncle named Mordecai. The family claimed to be of Welsh and English descent, but genealogical records indicate there may have been some Cherokee Indian heritage as well.

Mordecai had seven brothers and sisters. One of his brothers, John, also played baseball. According to Mordecai’s great-nephew, Fred Massey, John was as good as Mordecai though he never played above the semipro level because he didn’t apply himself.

In his playing days, Mordecai Brown was 5-feet-10 and weighed 175 pounds. Although not considered a large man by today’s standards, he was often referred to as “big” by contemporary baseball commentators. Brown was a switch hitter.

Mordecai’s most familiar nickname was Three Finger, although he actually had four and a half fingers on his pitching hand. Because of childhood curiosity, Mordecai lost most of his right index finger in a piece of farming equipment. Not long after, he fell while chasing a rabbit and broke his other fingers. The result was a bent middle finger, a paralyzed little finger, and a stump where the index finger used to be.

Mordecai’s other nickname also described him. He was called Miner Brown because he worked in the coal mines when he was a teenager.

In those days the working class found relief from the daily grind by playing baseball. The mining towns near Mordecai’s home had their own teams, and Mordecai played for Clinton, Shelburn, and Coxville. While playing third base for Coxville, Mordecai was called on to fill in for Coxville’s regular pitcher against the neighboring town of Brazil. The year was 1898, and the pitcher’s absence turned into a blessing for Mordecai.

Brown’s deformed hand enabled him to throw a bewildering pitch with lots of movement. Although the jumping ball was a problem when Brown was an infielder, it was an advantage when he pitched. Despite having what had seemed like a terrible handicap, Brown’s pitching performance that day was daunting. The Brazil manager was impressed, and the team offered Brown more money to play for them, but he didn’t jump until he’d completed the season.

In 1901 Mordecai, with the help of 600 fans who threatened to boycott the games if he didn’t make the team, secured a spot on the Terre Haute Tots (or Hottentots) in the newly formed Three-I League. Mordecai led the semiprofessional team to the first-ever Three-I championship, posting a 25-8 record.

Mordecai was picked up by Omaha in the Western League the following year, and reporters started calling him Three Finger. He became the staff workhorse, posting a 27-15 record and finishing every game he started.

After that season in Omaha, Mordecai joined the St. Louis Cardinals in 1903. His major-league debut for St. Louis, against Chicago of the National League, was similar to the outing in Coxville. In both games Brown pitched five innings, and his dominance over hitters was obvious to all observers. While his rookie record was not impressive, 9-13, it should be remembered that St. Louis was the last-place team that year in the National League, 46½ games back. Brown’s earned run average was the lowest on the team at 2.60, and his nine wins tied veteran Chappie McFarland for most on the team.

Mordecai and Christy Mathewson began their famous face-offs during Brown’s rookie year. The first time they met, on July 9, they dueled through eight innings, not allowing a run. In the ninth inning the Giants got to Mordecai for three runs and beat the Cardinals, 4-2.

After the 1903 season, Brown and catcher Jack O’Neill were traded to the Chicago Cubs, the team Brown beat in his rookie appearance and the team for which he would set records that have not been broken to date. The Cardinals received veteran pitcher Jack Taylor, who was suspected of throwing games, and rookie catcher Larry McLean. The Cardinals, being the last- place team, were probably desperate for an experienced pitcher, and Brown had not yet proven himself. It was the Cubs, however, who benefited the most by the trade because Brown had his greatest years while pitching for Chicago.

After joining the Cubs in 1904, Brown improved his record to 15-10 and lowered his ERA to 1.86. Brown still holds the Cubs record for most shutouts (since 1900) with 48 and lowest career ERA of 1.80. In addition, Brown is the Cubs record holder for most wins in a season, 29 in 1908, and the lowest ERA in a season, 1.04 in 1906. When Brown joined the club he was already 27 years old, the same age as his manager, Frank Chance, and older than most of his fellow players.

Besides capturing the interest of the Cubs in his rookie year, Brown also caught the eye of Miss Sarah Burgham. They married December 17, 1903, in Rosedale, Indiana, shortly before he joined the Chicago team. The marriage lasted 45 years, until Mordecai’s death. Sarah died 10 years later on October 5, 1958. They had no children.

Brown’s greatest years were during his tenure with the Cubs, 1904 to 1912, when he won 186 games and had six straight seasons, from 1906 to 1911, posting 20 or more wins. During that time he led the Cubs to two World Series championships.

His best year was 1906 when his winning percentage was .813. He pitched nine shutouts that year, and his 1.04 ERA is baseball’s third best in a single season. The Cubs won a remarkable 116 games in 1906 but lost the World Series to their cross-town rival White Sox, known as the Hitless Wonders because the team’s batting average was a weak .230. Mordecai won one of the World Series games, but one he lost, Game Six, 8-3, lifted his series ERA to 3.66. However, Mordecai could not have been called the Hitless Wonder. At the plate, he went 2-for-6.

The following year was also a good one for Three Finger Brown. In 1907 he posted a 20-6 record and an ERA of 1.39. That year the Cubs did win the World Series, beating the Detroit Tigers in five games. In that series Brown pitched in only Game Five, winning 2-0.

Brown continued his winning ways. In 1908 he posted an ERA of 1.47, second to Christy Mathewson’s 1.43.

But if one could ask him when his greatest game was, as many did when he was still living, he’d say October 8, 1908, at New York’s Polo Grounds. In John P. Carmichael’s My Greatest Day in Baseball, Brown said, “I was about as good that day as I ever was in my life.” That was the day the Giants and Cubs met for a playoff game to determine the National League championship.

The game was made necessary because of the “Merkle Play.” In the ninth inning during the September 23, 1908, game between the Giants and the Cubs, young Fred Merkle failed to touch second base on a play that should have scored the winning run for the Giants. Johnny Evers, remembering a similar play earlier when the call had not gone his way, solicited the ball Al Bridwell had hit. Whether he got that ball or another one is uncertain, but he stood jumping up and down on second base until he captured the umpire’s attention. Merkle was called out. Because the field was overrun by fans who thought the game was over, it was decided the game would be declared a tie, only to be replayed at the end of the season if it became necessary. It did. At the end of the season the Chicago Cubs and the New York Giants were deadlocked at the top of the National League standings.

In Brown’s How to Pitch Curves, an instruction manual written for young boys and published by Chicagoan W.D. Boyce, Brown referred to that playoff game as a time when having nerve served him well in baseball. He had plenty of “pluck,” as he put it, to pitch in front of a hostile crowd after receiving death threats. Gambling was commonplace in those days, and many had everything they owned riding on that game.

Jack Pfiester started the game for Chicago, and Christy Mathewson took the hill for New York, a repeat of the Merkle game match-up. Mordecai had started or relieved in 11 of the Cubs’ last 14 games so manager Frank Chance decided not to start his ace. The crowd was enormous; some accounts put the total at 250,000 spectators, taking into account the throng outside the gates. While that number is highly unlikely, people did fill every available space inside and outside of the Polo Grounds, lining fence tops, sitting on the elevated train platform, and perching on housetops.

The Giants rocked Pfiester in the first inning, scoring their first run. Not willing to take any chances, Frank Chance called on Mordecai. Pushing through the overflow crowd, Brown made his way in from the outfield bullpen and went on to win his 29th regular season game, securing the Chicago Nationals a third straight pennant and sending them on to play the Detroit Tigers and Ty Cobb in the World Series.

After the game, believing the Cubs had stolen the pennant from their team, New York fans threw hats, bricks, and bottles at the Chicago players. Frank Chance received a blow from a spectator that so injured his throat he couldn’t speak for days. The riotous atmosphere required a police escort for the Cubs by paddy wagon.

The following World Series must have seemed anticlimactic. Despite the opener in which Chicago scored five in the ninth to win 10-6—a win Brown received after relieving in the eighth inning—there were no amazing feats to compare with the October 8 playoff. Mordecai also won Game Four, 3-0. Detroit won only Game Three, even with Ty Cobb, American League batting champion, batting .368 in the series. The final game still holds the record for the lowest fan attendance in a World Series game. Only 6,210 Detroit fans showed up to see the Cubs defeat the Tigers.

Ty Cobb once described Brown’s lively pitch as the most devastating he’d ever tried to hit. His words are forever enshrined on a marker erected to Mordecai Brown in Nyesville, Indiana. It is high praise from a man who had remarkable success at the plate during the time when the ball had little juice. In his career, Brown won five World Series games for the Cubs and lost four. Cobb hit .273 off Brown during World Series play, but Brown won every World Series game he pitched against Cobb and the Tigers.

During the Deadball Era defense was king. The ball didn’t travel far, unlike today, and low scoring games were common. Teams couldn’t afford costly errors. Brown was an excellent fielder. In 1908 he handled the ball without error in 108 chances.

The rivalry continued between Brown and Christy Mathewson throughout their careers. Brown lost to Mathewson on June 13, 1905, a no-hitter for Matty, but after that he beat the Giants star nine consecutive times. The ninth game was the October 8 replay of the Merkle game.

The Cubs in those days were a rowdy bunch. Fights in the clubhouse were common, sometimes landing players in the hospital. But Brown was well respected. A search in Brown’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame produced a quote from teammate, Johnny Evers. Evers described Brown as having “plenty of nerve, ability, and willingness to work under any conditions. He was charitable and friendly to his foes.”

By 1912 Brown had lost his previous form. By that time he was 35 and only appeared in 15 games, posting a 5-6 record. After the 1912 season, ailing from a knee injury, he was traded to the Cincinnati Reds, where he went 11-12.

In 1914 Brown joined with other big leaguers and jumped to the short-lived Federal League. There he was player/manager for the St. Louis team before going to Brooklyn. Between the two teams he was 14-11 with a swelling ERA of 3.52. When he joined the Chicago Federals in 1915, he improved to 17-8 with an ERA of 2.09, and his team won a championship.

When the Federal League folded, Brown returned to the Cubs. His records indicate that major league dominance was behind him. At age 39 he made only 12 appearances, winning two games and losing three. His ERA was his highest ever at 3.91. Brown’s final game in the majors was September 4, 1916, the final face-off against rival Christy Mathewson, now pitcher and manager for the Cincinnati Reds. The Labor Day event was highly promoted and turned out to be the last big-league performance for both pitchers. Although Mathewson won that day, Brown slightly bested him over all, going 12-11 with one no-decision in their 24 matchups.

With his big-league years behind him, Brown accepted an invitation from his old Cubs teammate, Joe Tinker, now manager of the Columbus Senators of the American Association, to pitch in Ohio’s capital. Brown was 40 years old by then and posted a 10-12 record. Mordecai filled in as manager whenever Tinker was out scouting players. An article in the July 11, 1918, Columbus Citizen, notes that while playing in Louisville, Brown received more applause than the home team did. His popularity may in part explain the large fan attendance Columbus enjoyed while he played there. In 1917 the Senators drew just under 105,000—in a city with a population not much larger than that. In 1918 he appeared in only 13 games, but that was a year shortened by war and the flu outbreak.

In 1919 Brown went back to Terre Haute, Indiana to manage his former semipro team. Later that year, after Terre Haute’s season was completed, he joined Indianapolis of the American Association, but made little contribution to their pennant aspirations. His last year pitching was 1920, but after that he kept his hand in the game by managing oil company teams and buying an interest in the Terre Haute team.

Later in life Brown owned and operated a gas station in Terre Haute. He remained popular, occasionally showing up in newspaper reports about old-timer games or columns about players’ lives after baseball.

In his 14 years in the majors, Brown won 239 games and lost only 130. He led the league in wins once, in 1909, and led the league with most shutouts in 1906 and 1910. He had a lifetime ERA of 2.06 and from 1906 to 1911 he posted 20 or more wins—numbers sparking the attention of the Hall of Fame Committee on Baseball Veterans. He was elected in 1949. He may have known he was being considered for election, but he didn’t live to see it because he died on February 14, 1948, in Terre Haute, Indiana at the age of 71.

Forty-six years after Mordecai Brown died, his relatives, led by great-nephews Joe and Fred Massey, erected a three-foot-high granite stone to mark the birthplace of Nyesville’s famous son. On July 9, 1994, on land donated by farmer David Grindley, family and friends of the legendary three-fingered pitcher gathered to remember him. The author of this biography, cousin to Mordecai Brown, was in attendance.

In How to Pitch Curves, Mordecai leaves a farewell, “I would like to meet every one of you personally if such a thing were possible. But as it isn’t possible, I want you to believe right now that Mordecai Brown’s hand is reaching out to you in the distance and he is wishing you—good luck.”

Last revised: May 4, 2021 (zp)

An updated version of this biography is included in “Nuclear Powered Baseball: Articles Inspired by The Simpsons Episode Homer At the Bat” (SABR, 2016), edited by Emily Hawks and Bill Nowlin. It originally appeared “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Sources

Anderson, David W., More Than Merkle (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000).

www.baseball-almanac.com

Brown, Scott, personal family collection

Brown, Mordecai, How to Pitch Curves (Chicago: W.D. Boyce Company, 1913).

Carmichael, John P., My Greatest Day in Baseball: Forty-seven Dramatic Stories by Forty-seven Stars (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), c.1945.

National Baseball Hall of Fame Research Library, Mordecai Brown file.

Full Name

Mordecai Peter Centennial Brown

Born

October 19, 1876 at Nyesville, IN (USA)

Died

February 14, 1948 at Terre Haute, IN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.