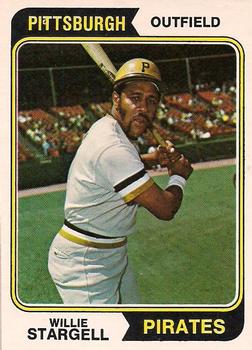

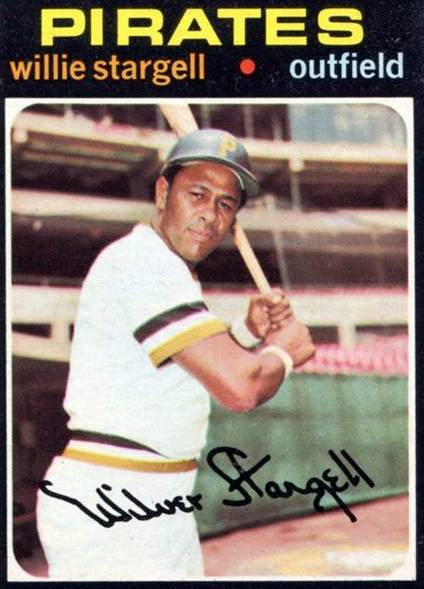

Willie Stargell

Following the Pittsburgh Pirates’ loss to the Chicago Cubs on October 1, 2000, 60-year-old Willie Stargell emerged to throw a ceremonial final pitch at the soon-to-be-demolished Three Rivers Stadium. Even though most people who followed the Pirates knew “Pops” was in poor health his frail, spectral appearance that afternoon was shocking. He was almost unrecognizable, barely able to walk on his own, a much-too-large gold Pirate jersey drooping pitifully from his emaciated shoulders. His feeble toss to catcher Jason Kendall barely went 10 feet.

Following the Pittsburgh Pirates’ loss to the Chicago Cubs on October 1, 2000, 60-year-old Willie Stargell emerged to throw a ceremonial final pitch at the soon-to-be-demolished Three Rivers Stadium. Even though most people who followed the Pirates knew “Pops” was in poor health his frail, spectral appearance that afternoon was shocking. He was almost unrecognizable, barely able to walk on his own, a much-too-large gold Pirate jersey drooping pitifully from his emaciated shoulders. His feeble toss to catcher Jason Kendall barely went 10 feet.

The poignant image of the dying man on the field that afternoon contrasted so dramatically with the mighty and fearsome slugger of an earlier time. It wasn’t long ago, with his mile-long home runs and gentle giant persona, that Willie Stargell seemed almost indestructible.

His childhood was not only challenging but also a little bit weird. Wilver Dornel Stargell was born March 6, 1940, in tiny Earlsboro, Oklahoma, the son of William and Gladys Vernell Stargell. (His unusual first name was an amalgamation of his father’s first name and his mother’s maiden name). But before Willie was born, his dad skipped town. It wasn’t until 1960, when Stargell was 19, that the two men finally met. “I accepted my father as he was,” Willie insisted later. “I didn’t offer judgment on what he had done and eventually I grew to love him for what he was.”1

Into the breach stepped Will Stargell, Willie’s biracial paternal grandfather (Will’s own father was a former slave. His mother was Seminole). Will took Gladys and Willie into his home and served as a surrogate father until three years later, when Gladys remarried and took her son with her to California. After Gladys’ second marriage ended quickly, she moved in with a relative in the public housing projects of Alameda, just outside of Oakland.

Gladys married again in 1946 but before the newlyweds could get on their feet financially, her older sister Lucy swooped in out of nowhere with an offer she couldn’t refuse. The two women agreed Lucy would take Willie back to her home in Orlando and care for him there until Gladys and her new husband got settled.

Stargell’s unflattering description of his aunt made her sound like a wicked old crone from a fairy tale. “Lucy [was] large-boned, bowlegged, and with a pinch of snuff tucked loosely inside her lower lip, carried herself awkwardly, almost like a retired cowboy…[T]here was a switch always in sight and a scowl always on her face.” 2

Life in Florida with his aunt was almost a form of incarceration. Lucy, who was divorced and never had children of her own, kept her nephew under strict control, apparently intercepting letters and money that Gladys sent to Willie. He was malnourished and burdened with so many chores that he barely had a chance to be a kid. In the summers, Stargell would sneak out to play baseball while Lucy was at work. Inevitably, he would stay out too long and fail to finish his assigned tasks, which seldom failed to spark Lucy’s ire. “Spanking became a permanent part of my late afternoon routine,” he recalled.3

Gladys finally came to rescue her boy after six long, difficult years. Despite his hard childhood in Orlando, Stargell grew into a strong, athletic teenager after returning to California, learning baseball on the neighborhood fields in and around the projects. “White boys from richer families were given other alternatives such as the Boy Scouts, family vacations, and field trips…Baseball was all we had.” 4

At Encinal High School in Alameda, Stargell was probably only the third-best player on the team. Teammates Tommy Harper and Curt Motton, both of whom also went on to play in the majors, were more polished athletes at that point. Stargell was just a big raw-boned kid still growing into his body. He also wasn’t far removed from a fairly serious knee injury suffered while playing football. But Pittsburgh Pirates’ scout Bob Zuk spotted a glint of potential underneath Stargell’s crude skills and signed him for $1,500 in August 1958.

For 1959 the Pirates assigned Stargell to a Class-D team that represented the towns of Roswell, New Mexico and San Angelo, Texas. Nothing in his background prepared him for life traveling around Eastern New Mexico and West Texas, a region that, for African-Americans, was as inhospitable as anywhere in the Jim Crow South. “People treated me like a dog.” he remembered, in a rare moment of open bitterness.5 According to Pittsburgh sportswriter Roy McHugh, Stargell seldom discussed all he went through that season but the scars remained. “By his manner, you’d never be aware he carried this around with him. But he did.”6

Many restaurants in the area were white-only. On the road, while the white players dined in relative comfort, Stargell waited outside on the team bus, choking down homemade Spam and salami sandwiches. He and his minority teammates were not welcome at hotels or motels either, so they boarded at the homes of whichever people of color would take them in. The conditions typically were far from luxurious. “I lived on back porches in fold up beds.”7 On one trip, Stargell stayed with a woman who raised bait in her home. The darkness, humidity, and stench were so overwhelming it was like sleeping inside a tackle box.

Stargell said the turning point of his life and career came during a trip to Plainview, Texas that season. As he strolled to the ballpark, a man approached him and put a gun to his head. “Nigger, if you play in that game tonight, I’ll blow your brains out.” Even though he was terrified, he summoned the courage to take the field that evening. He later claimed that was the moment he became a man, more determined than ever to make it. “I couldn’t go back home to the projects where we had prostitutes, pimps, some muggers, and there was no telling what would happen…[Baseball was] an avenue out of the ghetto.”8

The young outfielder overcame the bigotry, ascended rapidly through the minors, and received the call to join the Pirates in September 1962. He was a little over his head as a rookie in 1963, but he asserted himself the following season, raising his average 30 points, blasting 21 home runs, and appearing as a pinch-hitter in the All-Star Game. The 1965 campaign was even better as he became a much more selective hitter and drove in 100 runs for the first time. Then came one of the best years of Stargell’s career in 1966, when he batted .315 with 33 home runs and finished third in the National League in OPS.

That breakout season established an impressive benchmark. So when Stargell fell from that level in 1967 and 1968 reporters, fans, and even some in the Pirate organization began to see him as a bit of an underachiever and focused increased attention on his shortcomings. Although Stargell had put up fine numbers and made three National League all-star teams, it somehow seemed he should have been doing more.

To be sure, Stargell’s game was not well-rounded. He was a graceless, plodding left fielder who hurt his team defensively. He had a strong, accurate arm and he did the best he could, but with his rickety knees he just couldn’t cover enough ground, especially in a park as spacious as Forbes Field. First base would have been a natural spot for him, and he did play there now and then, but the Pirates were in no hurry to displace their regular first baseman, hard-hitting Donn Clendenon. He also battled numerous minor injuries which kept him out of lineup for short stretches. In his 20-year career, Stargell never played in more than 148 games in a season.

Early in his career Stargell was nearly helpless against left-handed pitching, so much so that his managers often benched him against tougher southpaws. He didn’t make too much of a fuss about it, but he unquestionably thought he was getting a raw deal. “I’m the first to know left-handers bother me but if I see enough of them, I’m going hit them. Somebody got the idea I couldn’t hit left-handers, so they took me out of the lineup. But if I keep playing against them, I gotta hit ‘em.”9 The numbers, however, belie his argument. Through 1968, in nearly 500 career at-bats against lefties, Stargell batted a puny .192 with only 13 home runs.

Furthermore, Stargell’s conditioning was an ongoing source of frustration for Pirate management. He regularly came into spring training overweight, but took it to an extreme in the winter of 1966-67, ballooning to a flabby 235 pounds. General manager Joe L. Brown was furious. He fined his rotund left fielder and put him on a crash diet to get him down to a target weight of 215, which Stargell found absurd. “I played at 222 last year and had my best season.” At the end of May, he was hitting just .193. “Losing all that weight made me weak when the season started.”10 Eager to avoid a repeat of that debacle, the Bucs ordered Stargell work with a personal trainer the following winter. He reported to camp in the best shape of his life in 1968, but new manager Larry Shepard took one look at him and criticized him for being too muscle-bound. The guy couldn’t win. “Pie Traynor [said] if the Pirates left me alone and quit worrying so much about my weight, I’d become the greatest home run hitter in Pirate history,” Stargell wrote years later. “Pie was a wise old son of a gun.”11

But starting in 1969, several important pieces fell into place for Stargell as he transformed himself from merely a very good player into the most prolific power hitter of the 1970s. A dismal .237 season in 1968 persuaded him to take Roberto Clemente’s advice and switch to a heftier 38-ounce bat. “Suddenly the holes in his swing were gone,” remembered teammate Nellie Briles. “That’s when he really got dangerous. He stopped trying to pull everything.”12

Additionally, the re-hiring of manager Danny Murtaugh in 1970 put Stargell’s mind at ease. “When Danny first had to quit after the 1964 season because of his health, I felt like I was losing somebody.”13 He respected Murtaugh’s quiet, understated way of running the team, which was a refreshing change for Stargell, who never saw eye-to-eye with Shepard or, especially, Harry Walker, who rode him about his weight incessantly. Walker even picked a fight with Stargell for bringing his dog to spring training. “I needed Danny’s presence to re-kindle my confidence,” he said.14

But perhaps the most critical change came when the Pirates relocated to Three Rivers Stadium. Stargell once claimed he could have hit 600 home runs had he played his entire career somewhere other than gargantuan Forbes Field, which was a daunting 436 feet to center field and 408 feet to right-center. Shepard suggested as much, telling Baseball Digest in 1969, “Next year when he gets into the new park with its normal dimensions he’ll challenge Babe Ruth, Roger Maris, and all the home run records.”15

In 1971, his first full season in the new home park, Stargell quieted his doubters and made his mark on the national stage. He served warning early in the year, setting a major league record for the month of April with 11 home runs. Despite constant pain from a knee injury that would require offseason surgery, he went on to lead the majors with 48 home runs and drove in a career-high 125, which helped carry Pittsburgh to a National League East title. Stargell endured a dismal postseason, batting just .132 with one extra-base hit and one RBI. But Roberto Clemente picked up the slack as the Bucs knocked off the Baltimore Orioles to capture their first World Series title since 1960.

In 1971, his first full season in the new home park, Stargell quieted his doubters and made his mark on the national stage. He served warning early in the year, setting a major league record for the month of April with 11 home runs. Despite constant pain from a knee injury that would require offseason surgery, he went on to lead the majors with 48 home runs and drove in a career-high 125, which helped carry Pittsburgh to a National League East title. Stargell endured a dismal postseason, batting just .132 with one extra-base hit and one RBI. But Roberto Clemente picked up the slack as the Bucs knocked off the Baltimore Orioles to capture their first World Series title since 1960.

Stargell continued his bombardment of National League pitching over the next three seasons, with 33 home runs in 1972 and then a league-leading 44 in 1973. He also led the majors in RBIs (119) in 1973 and topped both leagues in OPS in both 1973 and ’74.

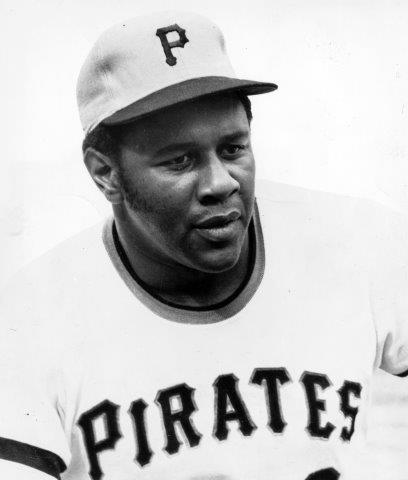

His impact, though, goes beyond those superb numbers. Although his statistics made him a star, it was his colorful persona and herculean strength that turned him into a beloved icon all around baseball, and especially in Pittsburgh. At 6-foot-2, Stargell was not a huge man but somehow he looked huge. He cut an imposing, swaggering figure and seemed to take perverse joy in messing with pitchers’ minds. Everything about him was intimidating. In his later years he took to loosening up in the on deck circle not with a weighted bat but with a sledgehammer. As he stepped into the box he glared out toward the hill, ominously pinwheeling his bat around and around as the pitcher read the signs. Stargell had massive forearms, powerful wrists, and preternaturally quick hands, and as the pitch came home he unleashed a swing that was effortlessly violent, like a man cracking a whip. Even when he came up empty, just the sheer power behind his swing was menacing.

Some players have hit more home runs than Stargell, but perhaps no one has ever been able to hit balls farther with such regularity. He was so strong and generated such tremendous bat speed that when he really laid into one the result was often a blast of absurd, almost cartoonish proportions. In 61 years, only 18 home runs cleared the right field roof at Forbes Field. Stargell did it seven times. Only six homers landed in the upper deck at Three Rivers Stadium. Stargell did it four times. Only four balls have been hit completely out of Dodger Stadium. Stargell did it twice. In 1978, he launched one 535 feet into the shadowy recesses of Montreal’s Olympic Stadium. The Expos organization commemorated the event by identifying the seat where the ball landed and painting it gold. As the Dodgers’ Don Sutton remarked, “He didn’t just hit pitchers. He took away their dignity.”16

As he emerged as one of the game’s great hitters, Stargell began to question whether he was being paid at a level commensurate with his talents. While baseball’s biggest earners, Henry Aaron and Dick Allen, raked in salaries in the $200,000 range, the Pirates reportedly paid Stargell less than half that amount. “I don’t feel right in their company,” he told a reporter in 1973. “I need money to be with Aaron and the others. When I’m in their presence, I know I am not in that class, even though I feel I belong,” adding, “You can damn near demand respect or command it if you got the money.”17 Stargell had made himself heard. In February 1974, the Pirates awarded him a new contract that made him one of the five highest-paid men in the game.

Stargell also was keenly aware of the lack of endorsement dollars coming his way. In a revealing interview with Ebony magazine in 1971, Stargell observed, “You see a few blacks [with endorsements] but that’s tokenism. Clemente has been shaving for years. I eat cereal every morning. Frank Robinson drives cars.”18 But yet those opportunities for broader media exposure and extra income were few and far between for Stargell and other black athletes. “[Steelers backup quarterback] Terry Hanratty has a TV show and he’s only been in Pittsburgh two years. Clemente has been here for 16 years and has done much more for the city and the first time I even saw Clemente on TV, outside of baseball, was on the Mike Douglas Show a year ago…That’s a shame.”19

Although Stargell sensed a lack of respect from society at large, he grew increasingly visible in Pittsburgh’s African-American community in the 1970s. “I think the black ballplayer should be responsible to the black community. The people, in many ways, helped put him where he is. He should be visible to the kids in the ghetto.”20 Stargell liked to pass out t-shirts on Halloween and deliver turkeys to poor families on Christmas Eve. On a larger scale, he created a foundation that raised hundreds of thousands of dollars to fight sickle cell anemia, a potentially lethal blood disorder particularly prevalent among African-Americans.

Stargell also opened a popular fried chicken restaurant in Pittsburgh’s predominantly African-American Hill District. Customers who were fortunate enough to have an order in when Stargell hit a home run got their meals for free. “You should see the people standing outside the store listening to their radios. They’ll all run in and order when Willie’s up,” marveled the store’s assistant manager. “Willie’s real popular here. Not just because he gives away chicken when he hits one, but he’s a real hero for baseball and for the blacks.”21

By the late 1970s, it looked like Stargell was almost finished. His decline began in 1975, his first season as a full-time first baseman, when a broken rib limited him to 124 games. The next year he missed significant playing time to care for his wife Delores, who was stricken with a brain aneurysm and spent six weeks in a coma. Statistically, it was one of the worst seasons of his career. “The ’76 season was hell. I couldn’t concentrate. I could only see Delores with all this equipment strapped on her and my mind drifted quite a bit.”22 By 1977, his wife was out of the hospital and on the path to recovery but his season ended in July when he wrecked his elbow during a bench-clearing brawl with the Phillies.

But then suddenly Stargell revived his career in 1978. He earned National League Comeback Player of the Year honors, batting .295 with 28 home runs and 97 RBIs despite sitting out 40 games. With his expanding paunch and arthritic knees Stargell looked every day of his 38 years — and maybe a day or two beyond that. But he still approached his job with the wide-eyed enthusiasm of a rookie. “When I think of old, I think of 300-year old sheep,” he joked. “It’s a shame people dwell on age, because they give in to it.”23

Stargell had acquired the nickname “Pops,” which suited him well as the elder statesman and emotional center of a raucous, ethnically diverse Pirate clubhouse. In 1978, he began awarding small stars to his teammates whenever they pitched well, came up with a big hit, or pulled off a brilliant defensive play. By the end of the season in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, players had their black caps festooned with gold Stargell stars. “I don’t mind if somebody takes my bat, my glove, or my uniform, but please don’t take my stars,” said second baseman Phil Garner. “I earned those and I deserve them.” 24

Left fielder Bill Robinson said Stargell became kind of a father figure to his teammates. “Willie was our crutch. Anything you needed, any problems you had personally or in baseball, he took the burden.”25 When Steve Blass was struggling with the inexplicable wildness that eventually ended his career, Stargell was there. “When it was my turn to pitch [in a simulated game], Willie would always say ‘I’ll be first.’ He did it every time. He would go into the cage without a batting helmet. It was almost as if he was saying, ‘Go ahead. Hit me in the shoulder. Hit me in the ribs. It doesn’t matter. Our relationship is stronger than that’…No one ever stood taller for me than Willie Stargell.”26

The 1970s had been a frustrating time for the Pirates. Following their 1971 World Series championship, they won three more National League East titles only to fall short in the NLCS each time. But in 1979, Stargell led them back to the promised land. His 32 home runs earned him a share of the National League Most Valuable Player Award. And in the postseason, where he had struggled so mightily eight years earlier, Stargell was a monster. He hit .455 in a three-game sweep of Cincinnati in the NLCS, then batted .400 with three home runs against Baltimore in the World Series. Just as they did in 1971, the Bucs rallied from a three-games-to-one deficit to take the Series in seven games. Stargell struck the deciding blow in Game Seven, a two-run homer in the sixth inning off Scott McGregor. For his heroics Stargell captured the World Series MVP award, while the Associated Press named him its Male Athlete of the Year.

The Pirates might have made it back to the postseason in 1980 if Stargell could have stayed in one piece. In just 67 games he homered 11 times and drove in 38 runs. But a July hamstring injury knocked him out for a month, and then recurring knee trouble ended his season prematurely. When he went on the shelf for good in mid-August, the Pirates were in first place; without him they went 16-28 the rest of the way and finished a distant third.

Stargell never played regularly again. He said by the early 1980s, “[m]y life revolved around pain.”27 Manager Chuck Tanner used him almost exclusively as a pinch-hitter the next two seasons. On Labor Day 1982, in the culmination of a season-long farewell tour around the league, the Pirates honored their captain by retiring his No. 8 in an emotional pregame ceremony. Stargell was such a widely respected and adored figure at this point that even President Ronald Reagan called to extend his best wishes.

Stargell’s retirement years were difficult ones in many ways. In 1984, he and Delores split after nearly 18 years of marriage. Although she appreciated her husband’s humanitarian spirit, she grew resentful of all the obligations he took on. “I said, how about your people at home? Charity begins at home.” She said she knew long before their divorce that the marriage was doomed. “Everybody was pulling at him every which way. [It was] awful. He was never around.”28

The following September at the Pittsburgh drug trials former teammate Dale Berra accused Stargell of providing him with amphetamines — a charge Stargell emphatically denied and which Commissioner Peter Ueberroth dismissed as ludicrous. Not long afterward the Pirates, under new ownership, dismissed Tanner, along with his entire staff, which included Stargell, who had just completed his first year as the team’s hitting coach. But Stargell soon re-joined his old boss down south, where Tanner had agreed to manage the Atlanta Braves in 1986.

Stargell endured a couple of awkward homecomings during his two-and-a-half years in a Braves’ uniform. Before one game in Pittsburgh a very young and already insolent Barry Bonds began hectoring Stargell with some trash talk. “Get out of here you old man!” Bonds hollered. “They forgot about you in Pittsburgh! I’m what it’s all about now!” Bonds meant no harm, really; he was just trying to be funny. But Stargell, who stalked away silently, wasn’t in on the joke. As Bonds scurried over muttering an apology, the normally affable Stargell turned and growled, “Boy, you better get some more lines on the back of your baseball card before you talk to me like that.”29

An even more unpleasant incident occurred in 1988 when Stargell, stung by the Pirates’ earlier refusal to consider him for their managerial opening, rejected the organization’s plans to hold a Willie Stargell Night to celebrate his first-ballot election to the Baseball Hall of Fame. According to some media reports, Stargell demanded the Pirates buy him an expensive sports car or hand over a percentage of gate receipts if they wanted him to participate. But Stargell insisted compensation wasn’t really the issue; his quarrel with Pirate management went deeper than that. “The last dealing I had with these Pirates, the new Pirates, the last thing they said to me was ‘You’re fired.’ I haven’t heard a word from the new Pirates since and then I hear they want to honor me.”30 When the Braves came to town a couple weeks later and the public address announcer introduced Stargell as the Braves’ third base coach, the crowd of 20,000 reacted viciously, raining down boos on the man who was once a civic treasure. Tanner was appalled. “I wanted to go out there at that moment and pat that guy on the back ten times and gesture to the fans. You don’t boo Willie Stargell….I felt so bad for the guy.”31

Stargell spent nearly a decade in the Atlanta organization, serving as a roving minor-league batting instructor after being dismissed with Tanner and the rest of his staff in May 1988. Then in 1997 Kevin McClatchy, head of the Pirates new ownership group, reached out to Stargell, mended old wounds, and welcomed him back into the Pirate family as an assistant to general manager Cam Bonifay.

But by this time, although Stargell was not yet 60 years old, his health was declining steadily. He was struggling with high blood pressure and since 1996 had suffered kidney problems that required dialysis three times a week. Shortly after rejoining the Pirates he required surgery to remove part of his bowel, a complication of his high blood pressure. “He came very close to not surviving that hospital stay. I consider it a miracle that he survived,” said his physician, James McCabe.32 In the fall of 1999, doctors amputated part of his right index finger after an infection set in.

Stargell entered a hospital near his home in Wilmington, North Carolina to have his gallbladder removed in February 2001. He never recovered, and died at age 61 after suffering a massive stroke on April 9. He was survived by his third wife, Margaret Weller-Stargell and five children. Coincidentally, Stargell died the morning of the first game at Pittsburgh’s new PNC Park. People laid flowers at the base of a statue of Stargell, which had been unveiled outside the stadium just days earlier. His death wasn’t completely unexpected but it was a body blow for fans and old teammates nonetheless. “When we heard about Clemente’s death at four o’clock in the morning, I went to Willie’s house,” Steve Blass told a reporter. “I’m not sure where to go this morning.”33

At the time of his retirement, Stargell’s 475 home runs tied him with Stan Musial for 15th on the all-time list. As legendary a power hitter as he was, one is still tempted to ask, “What if?” What if he hadn’t played eight-and-a-half years in the home run graveyard of Forbes Field? What if his knees had held up? What if he had been more serious about staying in shape early in his career? Four-hundred-seventy-five home runs, of course, is an extraordinary achievement. But one could imagine how a consistently healthy, consistently fit Stargell shooting at a more inviting right field porch could have boosted that total to well over 500; maybe even, as he suggested himself, close to 600.

But this man was more than a home run total. When 55,000 people embraced an ailing Willie Stargell with a standing ovation on that October afternoon in 2000, it was only partly about statistics and championships. Pirate fans were saying “thank you” for two decades of memories, while also saluting his impact as a leader both in the clubhouse and in the city that adopted him and made him its own.

This biography appears in “When Pops Led the Family: The 1979 Pitttsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Gregory H. Wolf.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted:

Baltimore Afro-American

New York Times

Time

Skirboll, Aaron, The Pittsburgh Cocaine Seven (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2010).

Notes

1 Willie Stargell and Tom Bird, Willie Stargell: An Autobiography (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 78.

2 Stargell and Bird, 13.

3 Stargell and Bird, 21.

4 Stargell and Bird, 42.

5 Randy Roberts, Pittsburgh Sports: Stories From the Steel City (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2002), 198.

6 Dave Kindred, The Sweetheart Called Pops,” The Sporting News, May 7, 2001.

7 Roberts, 198.

8 Ellenburg (Washington) Daily News, March 25, 1976.

9 Les Biedermann, “Stargell Startles Bucs’ Foes With Cannonading,” The Sporting News, July 4, 1964.

10 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 1, 1967.

11 Stargell and Bird, 118.

12 USA Today, April 10, 2001.

13 Bruce Markusen, The Team That Changed Baseball: Roberto Clemente and the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates (Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, 2006), Kindle DX version, Retrieved from Amazon.com, Chapter 5, para. 39.)

14 Stargell and Bird, 118.

15 Baseball Digest, December 1969.

16 Los Angeles Times, April 10, 2001.

17 Roberts, 200.

18 Lacy J. Banks, “Big Man, Big Heart, Big Bat,” Ebony, October 1971.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 St. Petersburg Times, June 11, 1971.

22 Sports Illustrated, August 20, 1979

23 Ibid.

24 The Daily Collegian, September 26, 1979.

25 John McCollister, John, Tales from the 1979 Pittsburgh Pirates: Remembering “The Fam-A-Lee” (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2005), 40.

26 McCollister, 39, 42.

27 Stargell and Bird, 237.

28 Jimmy Scott, “The Dee Stargell Interview, Pt. 1, Jimmy Scott’s High and Tight,” Retrieved June 13, 2011 from http://www.jimmyscottshighandtight.com/node/1035.

29 Jeff Pearlman, Love Me, Hate Me: Barry Bonds and the Making of an Antihero (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 89.

30 Pittsburgh Press, May 22, 1988.

31 Ibid.

32 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 10, 2001.

33 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 10, 2001.

Full Name

Wilver Dornel Stargell

Born

March 6, 1940 at Earlsboro, OK (USA)

Died

April 9, 2001 at Wilmington, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.