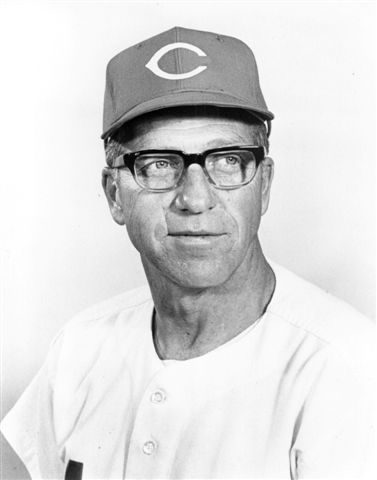

Larry Shepard

Serving as the pitching coach for the Big Red Machine is a bit like being the drummer in Billy Joel’s band. Even if you’re an integral part of an exceptional team, only the most devoted and hard-core observers will ever know your name as opposed to the headline-grabbing main attraction. While the Reds’ offense and its stars made headlines as the force that drove the Machine, Larry Shepard and his pitchers did more than hold up their end of the bargain as Cincinnati became the National League’s dominant force in the 1970s.

Serving as the pitching coach for the Big Red Machine is a bit like being the drummer in Billy Joel’s band. Even if you’re an integral part of an exceptional team, only the most devoted and hard-core observers will ever know your name as opposed to the headline-grabbing main attraction. While the Reds’ offense and its stars made headlines as the force that drove the Machine, Larry Shepard and his pitchers did more than hold up their end of the bargain as Cincinnati became the National League’s dominant force in the 1970s.

Lawrence William Shepard was born on April 3, 1919, in Lakewood, Ohio, just to the west of Cleveland. He was the third of four sons born to Frank and Viola Shepard, joining older brothers Frank and Richard, and later joined by younger brother Robert. Shepard’s father worked as a general agent at a steamship office, while his mother stayed home with the boys. Four years older than Larry’s father, Viola was raised by German-born parents and was a widow when she married Frank in 1913. In 1933 the family moved to Montreal, Quebec. Larry attended the city’s McGill University.

Shepard made his professional baseball debut in 1941 as a right-handed pitcher with the Trois-Rivieres Renards of the Class C Canadian-American League. The 22-year-old won 15 games and lost 11, to finish tied for tops on the team in wins, and second in innings pitched and ERA. The Trois-Rivieres club sold Shepard’s contract to the New York Giants, but in November, with the United States on the verge of entering World War II, Shepard enlisted in the Army, and the deal was nullified. Shepard missed the next four seasons while in the Army.

After he returned to baseball in 1946, Shepard spent six seasons pitching in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ minor-league system. After two good but not special seasons at Nashua and Pueblo, in 1948 Shepard became the player-manager of the Class D Medford Nuggets in the Far West League. It proved to be a banner year for Larry, as the team finished in second place, he posted a 22-3 record (leading the league in victories), and married Joyce Hamilton.

For the next three seasons Shepard was the pitcher-manager for Billings in the Pioneer League. The stay in Billings marked the high point of his playing career; as he logged three straight 20-win seasons and led the team to the league championship in 1950.

After the 1951 season Shepard, by then in his 30s, was drafted out of Billings and the Brooklyn organization by the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League, an affiliate of the Pittsburgh Pirates. At Hollywood Shepard was exclusively a pitcher; the team was managed by Fred Haney, who would go on to win a World Series managing the Milwaukee Braves in 1957. For the Stars, Shepard, pitching mostly in relief, was 6-4 with an ERA just over 3.00 in 107 innings as Hollywood won the PCL championship.

Shepard again became a playing manager in 1953, with Charleston of the South Atlantic League, then spent two seasons in Williamsport of the Eastern League before going to the Lincoln Chiefs of the Western League in 1956. So taken were the Shepards with Lincoln, Nebraska, that they made the city their permanent home.

Shepard pitched in 18 games while managing Lincoln in 1956 but, at 37, left the playing field in 1957. Lincoln won the league championship both of his seasons there.1 The team was run by Dick Wagner, who two decades later was instrumental in bringing Shepard to the Reds.

Promoted to manager of the Pirates’ Triple-A team in Salt Lake City in 1958, Shepard had a brief swan song as a player, pitching in seven games as a 39-year-old. In 1959 he led Salt Lake City to the PCL championship. In 1961 the Pirates moved Shepard to the Columbus Jets of the International League and immediately won the league championship, a notable achievement because the team had so many injuries that Shepard was forced to use 23 different infield combinations.2 The Jets won the title under Shepard’s guidance again in 1965. Having won five minor league championships and having prepared players such as Donn Clendenon, Steve Blass, Dock Ellis, Manny Sanguillen, Manny Mota, Wilbur Wood, and Willie Stargell for the major leagues, Shepard moved on after the 1966 season. He had hoped to take over the major-league club when it needed a new manager before the 1965 season, but was passed over for Harry Walker. Shepard instead became the pitching coach with the Philadelphia Phillies for the 1967 season,3 his first major-league job after 25 years in professional baseball.

The 1967 Phillies finished fifth with a record of 82-80. The pitching staff posted an ERA of 3.10, fourth in the National League. After the season Shepard worked with the Phillies team in the Florida Winter Instructional League. And while he was in Florida he got the chance he had waited for his entire career; he was named manager of the Pirates, at least partly due to his familiarity with the many Pirates he had managed in the minor leagues.4 The Pirates had had Shepard in mind since early September, when the Phillies played in Pittsburgh and Shepard talked about the job with Pirates general manager Joe L. Brown. (Manager Walker had been fired on July 18.) After he was hired Shepard said, “I had been walking on air ever since I first met with Brown and waited daily for this phone call. I phoned my wife right away because she was slowly developing an ulcer. This is our dream come true.” In addition to taking over a dream job as a major-league manager, Shepard got a salary about twice as much as the most he had ever made in one minor-league season.5

The 1967 Pirates had finished in sixth place, and Danny Murtaugh managed the last 78 games. Shepard set his sights high. “I’m shooting for the pennant,” he said. “I’ll be disappointed if the Pirates don’t win it because I think we have what it takes.”6 The Pirates began the Shepard era with an opening night one-game series at Houston. Joyce Shepard and the couple’s 12-year-old son, Larry, traveled to Houston for the game, and the Pirates led 4-2 heading into the bottom of the ninth. The Astros scored three runs after two were out to win the game and spoil Shepard’s debut as skipper.

Shepard took the loss hard. He dressed in silence and uttered not a word on the team’s midnight flight from Houston to San Francisco, where the Pirates were to begin a series the next day. Later he said, “I take defeats hard. And I try to take them myself. I don’t want to talk and don’t like people talking to me.”7 As the season progressed and the team struggled, Shepard had difficulty sleeping and maintaining an appetite; he lost nearly 30 pounds. He described a ten-game losing streak in July as “the worst experience of my life.”8

Sleepless nights, ten-game losing streaks and all, Shepard guided the Pirates to an 80-82 record and a sixth-place finish (out of ten teams) in 1968, earning another one-year contract to prove his mettle as a manager. The 1969 team won its first four games and held second place into early June before alternately rising into third after falling back into fourth place the rest of the season in the new National League East. Showing his penchant for internalizing the wins and losses, Shepard missed about a week in July after suffering chest pains. He had not suffered a heart attack, but was kept in the hospital for several days as a precaution.9 Despite a respectable record of 84-73, Shepard was fired the morning after the Pirates’ doubleheader sweep over the Phillies before fewer than 3,000 home fans on September 25. At 50 years old and released from the job of his dreams, Shepard stood at the professional crossroads. He could not have known how nicely things would fall into place for him.

After being fired, Shepard returned home to Nebraska to evaluate the next step in his professional life. “I was a very discouraged and broken-hearted man at that point,” he said. “I could see my baseball career behind me.”10 But a brighter future beckoned. In October 1969 Cincinnati’s Bob Howsam hired Sparky Anderson as manager. Anderson knew Shepard from the time they had spent as rival managers in the International League, and Wagner respected Shepard from their time together at Lincoln. Anderson asked Shepard to be the Reds’ pitching coach, and Shepard accepted. Also added to the Reds staff was Alex Grammas, who had been Shepard’s third base coach with the Pirates.

Often the success of a manager or head coach in professional sports is dependent on the leader surrounding himself with good, capable people and allowing them to do their job. With the Reds, Anderson understood that he did not know a whole lot about pitching and that Shepard did, and Anderson more or less turned things over to him. Daryl Smith wrote in Making the Big Red Machine, “(Sparky) had two basic philosophies when it came to pitchers. First, he wasn’t going to listen to them; he was only going to listen to the expert, and the expert wasn’t the pitcher, it was pitching coach Larry Shepard. What his pitchers tried to tell him didn’t hold any weight. In fact, he didn’t care what they thought. What he did want to hear was what ‘Shep’ had to say. He trusted Shepard completely.”11

With that trust Shepard went about improving the performance of the pitching staff. The 1970 squad posted an ERA nearly half a run better than in the preceding season and decreased its home runs allowed from 149 to 118. Shepard stressed improving the pitchers’ level of conditioning (and throwing more change-ups). Not content to just talk about improved conditioning, he often led the staff in wind sprints.12 As the season wore on and the Reds ran ahead of the pack in the National League West, more attention was given to the turnaround among the team’s pitchers. Anderson credited Shepard. “I have not met with my pitchers since the spring,” he said. “I’ve turned them all over to Larry. Larry’s got the pitchers thinking like they’re a separate team. The pitchers want very badly to hold their end up. Then it’s up to the hitters to get the runs.”13

Amid all the acclaim for the Reds’ offense, Shepard was quick to stand up for his pitchers. “Granted that we are a hitting team with the likes of Pete Rose, Joe Morgan, Johnny Bench, and the rest, but our pitchers have to be doing their share for us to have enjoyed the success we have. But somehow, they’re the last to get recognition,” Shepard said.14

Shepard demanded a lot from his pitchers and placed high expectations upon them. He poked the staff by saying things like “It’s tough to win with the Reds because the offense doesn’t always score six runs.”15 Reds beat writer Bob Hertzel wrote that Shepard “complimented and chastised, punished and rewarded, psyched and created this staff.”16 Shepard rode the staff hard, and called them “dumb ass” when they messed up.17 Jack Billingham, who pitched under Shepard for six seasons, recalled Shepard as “always thinking, always teaching. Larry was a perfectionist.”18 Shepard sat next to the impatient Anderson during games, always available to answer any query from the notorious Captain Hook. Shepard, of course, was also available to call down to the bullpen at any moment to instruct a pitcher to begin warming up.

While he could be blustery and difficult, there was another side to Shepard. Steve Blass, who pitched for Shepard in the minor leagues and with the Pirates, fondly recalled him as a great instructor for young pitchers and referred to him as “(my) pitching dad.”19 He was a devout Catholic, loyal friend, and sometimes provider of comic relief. In 1976 amid the hoopla of Mark Fidrych and his practice of talking to the baseball, Shepard said that as a pitcher he had done the same thing, and had even gone so far as to smack the ball when it was getting hit too much. As a pitching coach with the Reds he would “kill” a baseball that wasn’t providing the desired results. Shepard would walk to the mound, take the ball from the pitcher and hit it a few times. “When a team makes a couple of errors or gets a couple of long hits, it’s time to kill the baseball,” he said. The intent was to break the tension and relax the pitcher.20 The comedy Shepard provided was not always intentional, however. Severely limited by hip and leg issues, he had a hip replacement and lost mobility in the process. Once he stood near the plate like a hitter as Billingham warmed up before a start, and he accidentally buzzed Shepard, who went sprawling and had to be helped up. Another time the pitchers were in a meeting in which Anderson was dressing them down, and as he turned to Shepard to ask if he had anything to add, Shepard tilted too far back in his chair and fell over as the staff struggled not to burst out in collective laughter.21

Together with the quick-triggered Anderson, Shepard mapped out a plan of “defense from the bullpen” in which the duo would allow the team’s offense to determine when a pitching change had to be made. The reliance upon the bullpen was made possible by the effectiveness of veteran relievers Pedro Borbon and Clay Carroll and later by the duo of Rawly Eastwick and Will McEnaney.

Despite the success of the team and the pitching staff, only five of the Reds’ 34 All-Star Game selections from 1970 to 1976 went to pitchers.22 But while the pitchers missed out on individual accolades, under the direction of Anderson and Shepard they piled up the only stat that really matters: wins. From 1970 through 1976 the team was 683-443 (.607), won five division titles, four pennants, and two World Series.

As the team began to disintegrate in the wake of the new free-agency era, Anderson was fired after the 1978 season following consecutive second-place finishes. Shepard and the rest of the staff were also let go, with all but Grammas offered other positions in the organization. Ever loyal to Anderson, Shepard declined and served as the pitching coach of the San Francisco Giants in 1979, where he took considerable blame for the decline in the pitchers’ performance from the previous season. After the 1979 season, Shepard retired at the age of 60 after 39 years in professional baseball.

In retirement Shepard returned to life in Lincoln full-time alongside his wife, Joyce. Living in the city that housed the University of Nebraska, Shepard routinely offered advice to Cornhusker pitchers. He stayed in Lincoln for the rest of his life; he was 92 when he died on April 5, 2011. Joyce and two brothers had died earlier. Larry was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Lincoln.

This biography is included in the book “The Great Eight: The 1975 Cincinnati Reds” (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Mark Armour. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1 Daryl Smith. Making the Big Red Machine: Bob Howsam and the Cincinnati Reds of the 1970s. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 64.

2 Eddie Fisher, “Darkhorse Jets Copped Int Flag Without .300 Hitter,” The Sporting News, September 20, 1961.

3 Les Biederman, “Shepard Given Task of Putting Some ‘Lion’ Into Lamby Bucs,” The Sporting News, October 28, 1967.

4 Les Biederman, “Optimist Brown Tells Buc Fans of ’68 Dreams,” The Sporting News, December, 16, 1967.

5 Biederman, “Shepard Given Task of Putting Some ‘Lion’ Into Lamby Bucs.”

6 Les Biederman, “Shepard Shoots For Flag in Bow as Bucs Skipper,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1968.

7 Les Biederman, “Shepard Learns the Hard Way; All Pilot Glitter Is Not Gold,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1968.

8 Les Biederman, “Why Do Managers Get Gray? Shepard Knows the Answer,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1968.

9 Bill Christine, “Bucs Leaving Ailing Shepard Behind,” Pittsburgh Press, July 14, 1969.

10 Ritter Collett. Men of the Machine. (Cincinnati: Landfall Press, 1977), 93

11 Smith, Making the Big Red Machine, 191-2.

12 Greg Rhodes and John Erardi, Big Red Dynasty (Cincinnati: Road West Publishing, 1997), 82-85.

13 Rhodes and Erardi, Big Red Dynasty, 85.

14 Collett, Men of the Machine, 93-94.

15 Rhodes and Erardi, Big Red Dynasty, 198-99.

16 Bob Hertzel, The Big Red Machine (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1976), 96.

17 Mark Frost, Game Six (New York: Hyperion, 200), 41.

18 Rhodes and Erardi, Big Red Dynasty, 198.

19 Bill Brink, “Obituary: Lawrence W. Shepard,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 8, 2011.

20 Collett, Men of the Machine, 94.

21 Rhodes and Erardi, Big Red Dynasty, 199.

22 Rhodes and Erardi, Big Red Dynasty, 199.

Full Name

Lawrence William Shepard

Born

April 3, 1919 at Lakewood, OH (USA)

Died

April 5, 2011 at Lincoln, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.