October 10, 1914: Bill James outduels Eddie Plank in Game Two

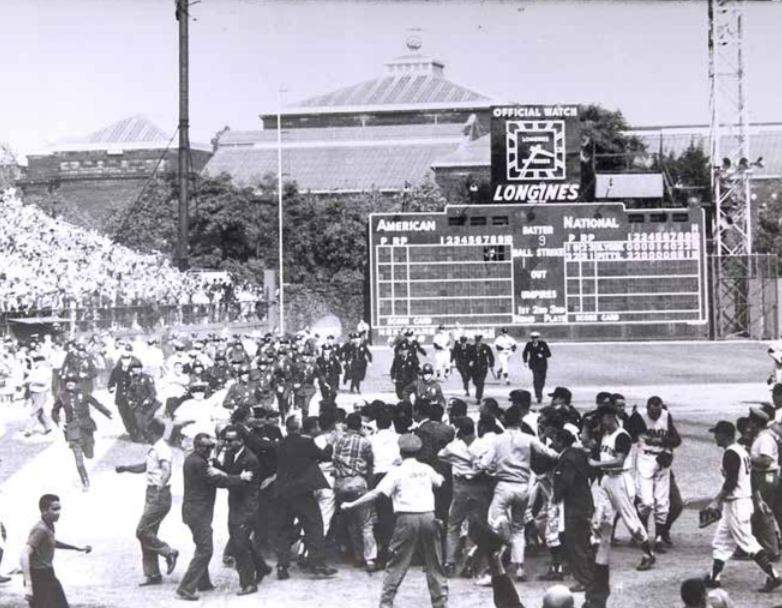

On an unusually warm October day in Philadelphia in front of more than 20,000 fortunate fans, the Boston Braves moved halfway toward winning the World Series for the first time with a dramatic 1-0 whitewashing of the Philadelphia Americans behind the brilliant two-hit pitching of Bill James, the unlikely ninth-inning offensive outburst of substitute third baseman Charlie Deal, and the defensive wizardry of Rabbit Maranville. The game represented a pitching duel for the ages featuring the veteran Eddie Plank and the youngster James.

On an unusually warm October day in Philadelphia in front of more than 20,000 fortunate fans, the Boston Braves moved halfway toward winning the World Series for the first time with a dramatic 1-0 whitewashing of the Philadelphia Americans behind the brilliant two-hit pitching of Bill James, the unlikely ninth-inning offensive outburst of substitute third baseman Charlie Deal, and the defensive wizardry of Rabbit Maranville. The game represented a pitching duel for the ages featuring the veteran Eddie Plank and the youngster James.

By their actions and their inactions, both George Stallings and Connie Mack made the ninth inning a particularly memorable one. In fact, the World Series gamesmanship had begun even before the Series. Deal was replacing Charlie Smith, who had broken his ankle in the last game of the regular season. Mack commented that he regretted the injury to Smith “as he wanted the Athletics to meet the Braves at their best,” words that would appear in a different light after Deal’s heroics.1

The “bats of the Boston visitors, which had been so efficacious against the speed and curves of Chief Bender,” had remained quiet as the scoreless game made its way to the final frame.2 Ever superstitious, Boston manager Stallings sought to spark his team by turning to a human good-luck charm in reserve outfielder Josh Devore,3 who replaced Game One winner Dick Rudolph on the first-base coaching lines in the ninth inning. By cause or by coincidence, Devore worked his magic quickly after Maranville grounded to Barry, his opposite number at short.

Deal lifted a fly to deep right-center field. “It was a long ball, but would not have been a difficult catch.”4 Amos Strunk, who “has always been classed with Tris Speaker for his ability in going back for balls,”5 broke in but misjudged and/or lost the ball in the sun, which “shone brilliantly upon the soft greens of the in and outfields.”6 By the time Strunk had reversed direction and retrieved the smash, Deal had reached second safely with his first safety of the postseason (he would get just one more hit in the Series) and Boston’s only extra-base hit of the game.

Wally Schang had Deal in trouble immediately, caught far off second base after a Plank pitch, but when Schang fired the ball to Jack Barry covering second, Deal daringly lit off for third and took the bag. “Barry did not throw to Frank Baker. He drew his arm back, but the throw never came. … Deal was directly in line with Baker and the throw might have hit the runner in the back and ended the chances of the Athletics right there.”7

Now, with no score, one out, and Deal on third base, Stallings faced a decision on his pitcher, James. Stallings had had both James and Lefty Tyler warm up before the game, but in a surprise to fans, who had expected to see Tyler perform,”8 chose right-hander James to start Game Two. (Mack also had Plank take batting practice before Game One but had gone instead with Chief Bender, his usual opening-game hurler.) Should he dispatch a pinch-hitter to bat for James, and perhaps get the first run of the game across the plate? But James, who was “working a fast one and quick-breaker spitter on the Athletics” in pitching to the minimum 24 hitters through the first eight frames, so Stallings let Seattle Bill bat for himself against Gettysburg Eddie.9 One can understand this decision given “the one game contributed by long Bill James was the most perfect piece of twirling skill seen in a world’s series in many a day.”10

To no avail. For the fourth straight time, Plank struck out his opposite number, which left Leslie Mann to face the southpaw with two down and Deal still on third in a game that had gone scoreless for its first 50 outs.

But Gettysburg Eddie faltered in the end. He forced Mann to go the other way, and the Bostonian “whacked a short safe one-shot that fleet, game Eddie Collins could not reach though he leaped four feet into the air and landed in a shapeless heap on the outfield turf.”11 The single plated Deal with what turned out to be the only run of the ballgame.

Plank ended up hurling 129, 132, or 149 pitches in and out of trouble all day.12 “Inning after inning the Braves got runners on the bases, and, just as they were about to strike their telling blow, gray-eyed Plank, still cunning and wily in the evening of his baseball career, suddenly would pull himself together and halt the Boston uprising.”13

In his syndicated column, Ty Cobb credited Stallings’ platoon system, one originally devised by Mack, for the run, writing, “(T)hat game was won by Stallings’ shrewd shifts. He put Mann and Ted Cather into his batting order in place of Moran and Joe Connolly, to get two right-handed batters against a southpaw, and how well it worked the result showed.”14

Having given the Athletics a pep talk before the game, Cobb hardly counted as an impartial observer but he still credited the Braves for heady play.

James, who had pitched unerringly after walking Eddie Murphy to start the game, struggled to hold the lead in the ninth, sandwiching walks to Jack Barry (on four pitches) and pinch-hitter Jimmy Walsh around a strikeout of Wally Schang. With the tying run on second and the winning run on first, James induced a hot shot through the box by Murphy that looked as if it would get through and tie the game.

But Johnny Evers had moved Maranville just to the right of the second-base bag, so Rabbit made three great plays in one by receiving the ball, brushing off the lumbering Walsh (Maranville “bounded away from Walsh like a rubber ball”15), and firing the pill to Butch Schmidt at first to turn a dazzling short-to-first double play, the game’s only twin killing and the only double play Murphy hit into in all of 1914. It ended the game and the Shibe Park season. “Maranville’s utterly impossible double play [saved] the whole show.”16

Maranville had more than made up for dropping Stuffy McInnis’ foul fly for a one-out error in the eighth inning, a miscue that could have been a major one so late in a scoreless duel but that James mitigated by inducing Stuffy to sky to Deal at third.

In addition to the ninth-inning dramatics, each team threatened to score throughout the game although James did retire 15 Athletics in a row after walking Murphy in the bottom of the first.

Plank, by contrast, saw Bostonians reach base frequently, but pitched in a pinch by stranding Braves in scoring position in the first, second, fourth, and sixth. Schang ended the third by throwing out Johnny Evers trying to swipe second “by such a distance that the long chinned Trojan seemed to be standing still.”17 Boston went down in order only in the seventh.

Deal’s dash for third in the ninth capped off a game that featured audacious but often overly-aggressive baserunning. The other successful swipes included Deal stealing second in the top of the second with two outs,18 and Barry stealing second during Schang’s ninth-inning fan.

In addition to Schang gunning down Evers, James picked off Murphy pitcher-to-first-to-shortsopt in the first, Hank Gowdy threw out Schang trying to take third on a pitch of the dirt after Wally had broken up James’s 15-in-a-row run with a sixth-inning two-bagger down the left-field line,19 and James picked off another batter – Collins this time – after Eddie had reached on an infield single to second with two outs in the seventh.

The final two baserunning mistakes for the Americans had similar outcomes but resulted in different reactions. Some, including Schang himself, thought Schang safe at third – postgame photographic evidence seemed to indicate that he had taken the bag – but umpire Bill Byron ruled otherwise.20 The Boston Evening American credited Gowdy with “pegg[ing] him out, assisted somewhat by a perfectly splendid and stout-hearted tagging stunt by our old acquaintance, slight Charlie [Deal].”21

Byron’s decision made Plank’s grounder to short an inning-ender rather than an RBI that would have scored Schang and given the Philadelphians a critical 1-0 lead. In his column, Cobb implied that Byron, a National League umpire, might have exhibited bias in his call. No such controversy resulted from the Collins play, in which James caught Eddie napping as the latter hung his head after failing to retreat safely back to first.

Evers saw this as swift and divine retribution by the baseball gods. Having thought that his snap throw had in fact beaten Collins to first base, Evers after the safe call “threw his hands over his head, and everyone knew what he meant.”22

Amazingly, Schang and Collins, the only two Athletics with base hits, both ended up making outs on the bases before a fellow Philadelphian could complete his turn at bat. Whether the Athletics took the Braves too lightly or failed to focus on the game with Federal League riches lingering in the minds of many ballplayers remains unclear; indisputably, however, in Game Two Boston played like a confident veteran bunch while the Mackmen made multiple mistakes, an odd state of affairs given that Philadelphia played Game Two, its fourth World Series in five years, in the friendly confines of Shibe Park.

The Braves did enjoy, however, a loyal and vocal fan base that made the trip from Boston to Philadelphia to cheer on the visitors and visit invective on the home team. The Royal Rooters, who had hassled Honus Wagner and his Pittsburgh comrades in 1903, stayed true to their city. Former Boston Mayor John Fitzgerald, known then as Honey Fitz and later as the grandfather of President John F. Kennedy, said “in the most courteous manner [that] Plank was one hundred years old, had a glass arm and was blind of one eye.”23

Taking two in Philadelphia left the brash Bostonians feel that their miraculous run would continue. Stallings told his equipment manager to pack the road uniforms of the Braves and take them home rather than leave them at Shibe Park. Stallings said, “We won’t be coming back. It’ll be all over after the two games in Boston.”24

Lest readers today accuse writers from yesteryear of spinning yarns in the afterglow of victory, Stallings’ players made similar statements at the time. Gowdy hardly hedged: “We’re out for four straight and it looks all the more and more that we were going to get them.”

Herbie Moran, who did not even play in Game Two, predicted flatly: “The Braves will win four straight.”25

Like the Chicago Cubs from 1906 to 1910, the only other team that then had reached the World Series with the same frequency as the Athletics, but had dropped off the pace due to age, the loss of Evers, and the lure of the Federal League, the end of this great Philadelphia squad seemed suddenly near.

Damon Runyon observed at the time, “The star of the American League seems to be slowly sinking.”26 Norman Macht wrote nearly a century after the game, “Nobody spoke in the home clubhouse after the game. Plank stood on a stool, head in his hands, while the others silently showered, dressed, and left.”27

One could hardly fault Plank, at least, for his efforts in defeat.28 He “pitched those nine exciting, thrilling innings just like the old master that he is. … Hats off to Ancient Edward, like his rival, Matty, as great, or greater, in defeat as ever he was in victory.”29

Newspaper reporters invoked Christy Mathewson when summarizing the efforts of both the losing and winning hurlers. “James … twirled a quality of baseball that would have been a credit to a Mathewson, a Johnson or a Rudolph.”30

In his own newspaper article, Manager Stallings paid tribute to his winning pitcher, writing of James: “To him, almost alone, belongs the verdict.”31

The last words belonged to the National League’s Chalmers Award winner in 1914, Johnny Evers, who, after all, had a better view of the game than any sportswriter or historian. Though viewed today as a fierce partisan rather than a dispassionate observer, Evers astutely and evenly summed up the compelling contest, stating, “Bill James pitched wonderful ball, but he had little on that old veteran Plank.”32

This article is included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 J.R. Cary, “Charles Deal, The Man Who Made Good in the Pinch,” Baseball Magazine, February 1915, 54. Massachusetts Governor David Walsh said after the game, “If I were Mr. Deal tonight I should not swap places with anybody on earth.”

2 Boston Evening Record, October 11, 1914, 2.

3 Devore “considers himself a lucky fellow. Devore was turned over to Cincinnati by McGraw last year. Cincinnati sent him to the Phillies, and from here he went to Boston. … He believes he is lucky because he was born on Friday the thirteenth.” In “Punch Your Head’ Stallings to Mack,” Philadelphia Bulletin, October 8, 1914, 17.

4 John I. Taylor, Boston Globe, October 11, 1914, 9. Taylor was the former owner of the Red Sox.

5 “World’s Series Echoes,” Sporting Life, October 17, 1914, 3.

6 Boston Evening Record, October 11, 1914, 1. The sun had affected flies earlier in the game as well: “Baker flew to Whitted, who lost the ball in the sun, but finally spotted it again and made a fine catch after a long run.” J.C. O’Leary, Boston Globe, October 10 (evening edition), 1914, 1. A little more than 15 years later, Chicago Cubs center fielder Hack Wilson would more famously lose a fly in the Shibe Park sun, a misplay that would help the Athletics win Game Four of their World Series 10-8 and eventually the Series in five games.

7 Damon Runyon, Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, 3 of special World’s Series section. In a newspaper column after the game, Barry himself wrote, “I didn’t throw the ball because I couldn’t. Schang’s throw to me was perfect, but the ball slipped out of my hand and popped up on the top of my fingers and I couldn’t throw it.” Jack Barry, “Ball Slipped from Barry’s Hand while Deal Was Stealing Third,” Philadelphia Bulletin, October 12, 1914, 12.

8 Boston Evening Record, October 11, 1914, 1.

9 Boston Evening Record, October 11, 1914, 1.

10 John J. Ward, Baseball Magazine, February 1915, 33.

11 Nick Flatley, Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, page 2 of a special World’s Series section.

12 Newspaper accounts of the game use the higher figures; a history uses the lower one. T.H. Murnane in the Boston Globe had 149, and the Philadelphia Inquirer had 132. Norman L. Macht had 129 in Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball. Both papers agree that James threw just 92 pitches. The Philadelphia Inquirer had James at 76 pitches through eight innings, with innings three through eight at no more than ten pitches per frame. James threw 16 pitches in the pressure-packed ninth, 13 more than he had thrown in his most stressful inning to that point, the second.

13 New York Times, October 11, 1914.

14 Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, page 1 of the special World’s Series section.

15 New York Times, October 11, 1914.

16 William A. Phelon, Baseball Magazine, February 1915, 12.

17 Damon Runyon, Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, page 3 of the special World’s Series section.

18 “Happenings by three seem to follow that Deal boy. In the first game he walloped into three (double) plays, and yesterday he three times forces runners again before he landed that long fly that Strunk misjudged.” “Braves Again Victors, Athletics’ Falter in Field with Bats Silenced,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 11, 1914, sports section 3.

19 “Wally Schang suddenly broke the monotony of hitless Athletics’ frames by driving a two-base hit past third, making second by sliding on his stomach and beating by a scant fraction of an inch a beautiful throw-in by Cather from deep left corner.” Ed McGrath, Boston Post, October 11, 1914, 11.

20 “Photographs of the play also show Schang on the base with Deal still waiting for the ball.” Hugh S. Fullerton, “Mack Keeps Men Secluded before Game in Boston,” [Philadelphia] Evening Ledger, October 12, 1914, 2.

21 Nick Flatley, Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, page 2, special World’s Series section. “‘It’s all over and there’s no use of complaining,’ said Schang, ‘but Deal hasn’t touched me yet on that play. I made a hook slide and caught the outside of the bag with my foot. Deal’s gloved hand swept around quickly but he never touched me. Byron called the play so quickly that he said I was out before the play was finished.’” “Mack and Braves Each Make a Tally Early in the Game,” Philadelphia Bulletin, October 12, 1914, 2. According to Retrosheet, Lord Byron was umpiring first base, not third base, in Game Two.

22 John J. Hallahan, Boston Herald, October 11, 1914, 2.

23 F.J. McIsaac, Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, page 4, special World’s Series section.

24 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 163.

25 Nick Flatley, Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, page 4, special World’s Series section.

26 Damon Runyon, Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, page 3, special World’s Series section.

27 Norman L. Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 642.

28 This was the last but hardly the first time when Plank lacked run support in the World Series: “Eddie Plank suffered his fourth shutout in world’s series battles.” “Braves Again Victors, Athletics’ Falter in Field with Bats Silenced,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 11, 1914, sports section p. 1.

29 Nick Flatley, Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, page 2, special World’s Series section.

30 Walter E. Hapgood, Boston Herald, October 11, 1914, 1.

31 George Stallings, Boston Evening American, October 11, 1914, page 4, special World’s Series section.

32 C.P. Stack, Baseball Magazine, February 1915, 73.

Additional Stats

Boston Braves 1

Philadelphia A’s 0

Game 2, WS

Shibe Park

Philadelphia, PA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.