October 8, 1940: Reds pitching prevails and Cincinnati celebrates first World Series title in two decades

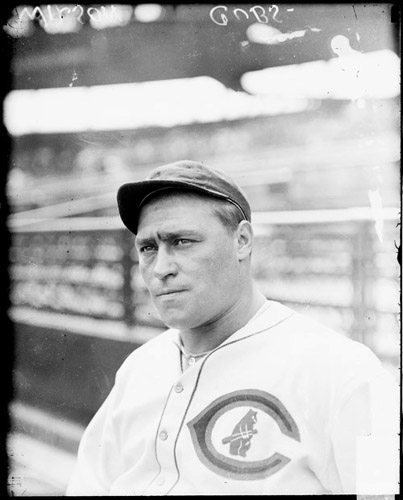

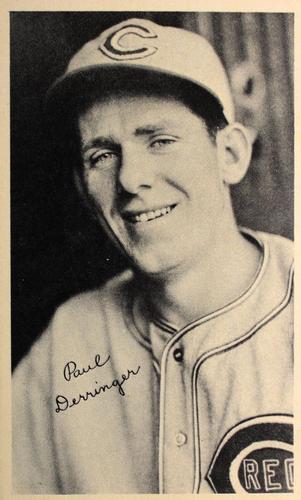

After Bobo Newsom shut the Reds out 8-0 in the fifth game of the 1940 World Series, giving the Tigers a lead of three games to two, Deacon Bill McKechnie was still confident of his team’s chances. After all, he had Bucky Walters and Paul Derringer ready for Games Six and Seven. Together they had accounted for 94 wins in the regular seasons of 1939-40.

After Bobo Newsom shut the Reds out 8-0 in the fifth game of the 1940 World Series, giving the Tigers a lead of three games to two, Deacon Bill McKechnie was still confident of his team’s chances. After all, he had Bucky Walters and Paul Derringer ready for Games Six and Seven. Together they had accounted for 94 wins in the regular seasons of 1939-40.

Perhaps more important than the Deacon’s optimism was the fact that Newsom had just pitched, which meant that, barring a rainout, Game Seven would be played in two days. That meant that Tigers skipper Del Baker would have to pitch Newsom on one day’s rest or go with one of his other starters, probably Tommy Bridges.

On the other hand, if Walters could keep the Reds alive with a win in Game Six, Derringer would have two days’ rest. Since the Series was being played on consecutive days, McKechnie was hoping the forecast that rain awaited them in Cincinnati would hold off.

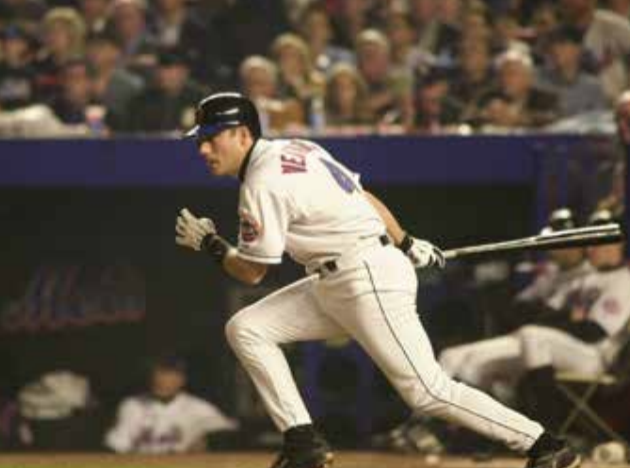

Bucky Walters, with one victory already under his belt in Game Two, came through with a 5-0 shutout in Game Six, with outstanding defense from the Reds, especially Bill Werber and Eddie Joost. The stage was set for the Game Seven showdown at Crosley Field.

The weather for the game was a perfect 67 degrees with a cloudless sky. The only thing puzzling about the day was the less-than-capacity crowd of 26,854. The city was abuzz with the possibility of the Reds winning their first Series since 1919. Since that one was somewhat tainted by the Black Sox scandal, a Reds win would be a monumental event – the old franchise’s first undisputed baseball championship. The celebration that awaited a victory would demonstrate that the populace was transfixed on the game, regardless of whether they were looking out windows on York Street or listening to blaring radios in the streets of the West End.

The game was decided in only two innings. In the Tigers’ third, Billy Sullivan led off with a single past first. Frank McCormick knocked it down, but Sullivan beat the throw to Derringer covering. Newsom sacrificed Sullivan to second. Dick Bartell then popped up to Joost. Derringer walked Barney McCosky, bringing up the dangerous Charley Gehringer, who smashed a hard grounder to third. Werber fielded the ball but threw wide of first, allowing Sullivan to score from second.

As the innings rolled by it began to look as if Newsom might make the one run hold up. In the Reds dugout, Bill Werber, whom many considered one of the team leaders, kept telling his teammates that if you stay close to Newsom, you can beat him.1 Werber had played against Newsom many times during his American League stints with the Red Sox and the Athletics.

Then came the Reds’ historic seventh inning. Frank McCormick led off with a double off the left-field wall. Jimmy Ripple stepped to the plate, and provided one of the most memorable moments in Reds history. The Brooklyn castoff drove a ball off the right-field screen. (Unlike other ballparks, a hit off the screen in Crosley Field was not a home run.) Everyone expected McCormick to score easily. However, to the horror and amazement of the Reds bench, McCormick was staying near second base. Eddie Joost commented, “Everybody in the ballpark except McCormick knew the ball wasn’t going to be caught.2 Finally, McCormick headed for third, and was waved home by McKechnie, who served as his own third-base coach.

Bruce Campbell made the relay throw to Bartell, who, with his back to the plate, and Reds fans screaming at the top of their lungs, then “put it in his pocket.”3 As Bartell tried to explain later, he had no reason to think about throwing out McCormick at the plate. A double off the right-field wall should have scored McCormick easily. Bartell saw that McCormick had hesitated after rounding third, but did not think he could get him at the plate. He later conceded that maybe a perfect throw would have gotten McCormick.4

It will never be known whether McCormick would have been out at the plate if Bartell, upon receiving the relay, had immediately thrown to home plate. Different observers had different opinions. Eddie Joost, who described McCormick and Ernie Lombardi as guys who looked as though they were running in mud up to their ankles, claimed that McCormick would have been out.5 Werber said only that it would have been a close play at the plate.6 The score was now tied, 1-1, with Ripple on second and nobody out.

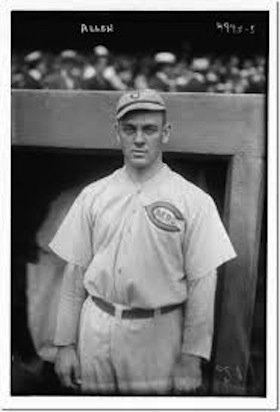

Jimmie Wilson then sacrificed Ripple to third. The next scheduled batter was Eddie Joost. McKechnie sent Lombardi up as a pinch-hitter. He was promptly given an intentional pass. Lonny Frey ran for Lombardi. With runners on first and third and one out, the light-hitting Billy Myers stepped to the plate. The Reds shortstop had hit only .202 during the regular season, and was hitting .136 in the World Series.

With what had to be the highlight of a mediocre career, Myers drove McCosky to the wall in center field to haul down his long drive at the 385-foot marker. Ripple scored from third and the Reds took a 2-1 lead going into the eighth inning.

This was the key inning for Derringer, as the Tigers were scheduled to send up their third, fourth, and fifth hitters – Charley Gehringer, Hank Greenberg, and Rudy York. When Gehringer opened the inning with a single to right, McKechnie sent both ace reliever Joe Beggs and Bucky Walters to the bullpen to warm up. Then, in what was perhaps the key out of the game, Hank Greenberg lined to Myers at shortstop. York and Campbell followed with flyouts to end the inning.

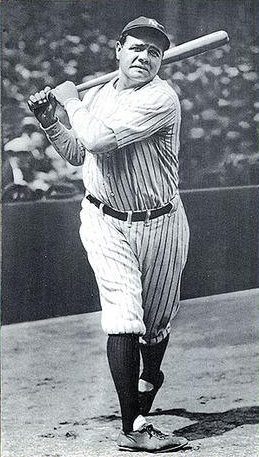

In the top of the ninth, the Tigers were due to send up Pinky Higgins, Billy Sullivan, and the pitcher. Beggs and Walters continued throwing in the bullpen. They wouldn’t be needed. Higgins and Sullivan were retired without a ball leaving the infield. Then Earl Averill, a future Hall of Famer nearing the end of his career, was sent up to hit for Newsom. When Lonny Frey fielded his routine grounder and threw to Frank McCormick for the final out, the fans both inside and outside Crosley Field erupted into bedlam. Seat cushions flew from the stands, and fans emptied onto the field to join in the celebration.

In the Reds locker room after the game, general manager Warren Giles had to stretch to shake the hand of Paul Derringer, who was hoisted on the shoulders of his grateful teammates.

On the streets of Cincinnati, confetti flew from the downtown skyline buildings as happy citizens celebrated a 21-year wait for the Reds to return to the top of the baseball world.

In the Tigers locker room, Del Baker’s comment was, “I don’t like losing, but if I have to, I’d rather lose to Bill McKechnie than anyone else I can think of.”7 Dick Bartell, answering why he thought the Reds won, said, “We didn’t win the Series because we didn’t hit, and the reason we didn’t hit is because of Walters and Derringer. They’re a better one-two punch than the Dean brothers.”8

As of 2016 Game Seven of the 1940 World Series remains the only time that the storied Cincinnati Reds franchise has clinched a World Series championship at home. The Reds won in 1919 at Comiskey Park, in 1975 at Fenway Park, 1976 at Yankee Stadium, and in 1990 in Oakland.

The Seventh Game of the 1940 World Series is either the most important game ever played at Crosley Field or shares the honor with the first night game ever played in major-league baseball, in 1935, also at Crosley. For overall baseball history, night baseball overshadows any singular baseball game played in any stadium. But for Reds history, that 1940 Game Seven tops the list.

This game marked the pinnacle of the careers of every Reds player except Eddie Joost, who went on to star for the Philadelphia Athletics after World War II. For all the others, although there were years when some of them performed at a high level, none returned to the glory of the magical 1940 season.

This article was published in “Cincinnati’s Crosley Field: A Gem in the Queen City” (SABR, 2018), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more articles from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Notes

1 Interview with Bill Werber, Naples, Florida, March 28, 1989.

2 Interview with Eddie Joost, San Jose, California, April 29, 1989.

3 Ibid.

4 Dick Bartell with Norman Macht, Rowdy Richard (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 2007), 303.

5 Joost interview.

6 Werber interview.

7 Leo Bradley, Underrated Reds, the Story of the 1939-40 Cincinnati Reds, the Team’s First Undisputed Championship (Cincinnati: Fried Publishing Company, 2009), 53.

8 Bartell with Macht, 295.

Additional Stats

Cincinnati Reds 2

Detroit Tigers 1

Game 7, WS

Crosley Field

Cincinnati, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.