Honus Wagner’s Short Stint as Pirates Skipper in a Forgettable Final Season

This article was written by Gregory H. Wolf

This article was published in The National Pastime: Steel City Stories (Pittsburgh, 2018)

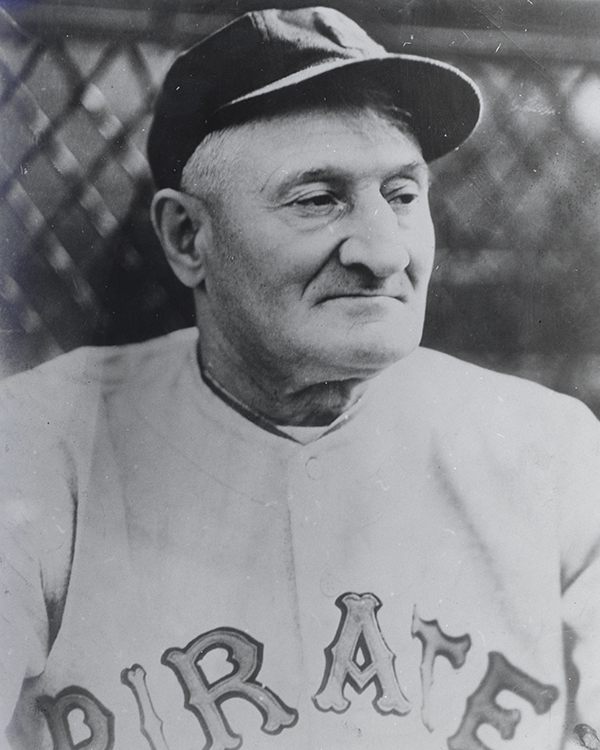

Honus Wagner, or Hans as he was almost universally called, was relieved the season was over. His 20th campaign in the big leagues and 17th with the Pittsburgh Pirates had been physically and emotionally draining. The 1916 season had been troublesome even before it started and had only gotten worse. Many had predicted Wagner would take the managerial reigns of the club in ’16 following the retirement of longtime Pirates skipper Fred Clarke, who had guided the Bucs to 14 consecutive first-division finishes (1900–13) and four pennants; however, the soft-spoken Wagner adamantly refused the job. “I would not be a manager,” he said, “because I would not want to leave the ball field and take my worries and troubles home with me.”1

Honus Wagner, or Hans as he was almost universally called, was relieved the season was over. His 20th campaign in the big leagues and 17th with the Pittsburgh Pirates had been physically and emotionally draining. The 1916 season had been troublesome even before it started and had only gotten worse. Many had predicted Wagner would take the managerial reigns of the club in ’16 following the retirement of longtime Pirates skipper Fred Clarke, who had guided the Bucs to 14 consecutive first-division finishes (1900–13) and four pennants; however, the soft-spoken Wagner adamantly refused the job. “I would not be a manager,” he said, “because I would not want to leave the ball field and take my worries and troubles home with me.”1

Jimmy Callahan accepted the job with a two-year contract, but the results were disastrous. The Pirates finished in sixth place with their worst winning percentage since 1914. The 42-year-old Wagner suffered through a myriad of injuries to his hands and hip, and was no longer the “Flying Dutchman.” He had lost more than a few steps and played in 92 games at shortstop, the fewest since moving to that position full-time in 1903, though he also made 23 starts at first base.

Wagner wasn’t sure if he’d be back with the Pirates in 1917. He concluded the season with the worst slump of his career, managing just 11 hits in his last 77 at-bats and scoring just one run in his final 23 games. His struggles intensified speculation that he would finally hang up his spikes. He hadn’t batted .300 since 1913, it was increasingly difficult for him to get into and stay in condition, and his days as an everyday shortstop were over. On the other hand, he was the most visible person in the Smokey City. Pittsburgh sportswriter Henry Keck called him “probably the most beloved man in baseball,” admired and praised by fans and press across the country as much for his accomplishments as for his upstanding character.2 There wasn’t much more he could do: He was a World Series champion, had collected the most hits (3,359) and runs (1,724) in big-league history, and was the active leader in home runs (101).

Cognizant of his eroding skills, Wagner needed a rest and also wanted to spend more time with 26-year-old Bessie Smith, a local Pittsburgher and his companion of eight years. Although he was an avowed bachelor who had pledged to remain one as long as he played baseball, Wagner’s attitude shifted that offseason after the sudden death of his oldest brother, Charley, from complications of pneumonia on October 31, 1916. The two siblings had been very close; Charley and his wife, Olive, and three children provided Hans a semblance of domestic life. Long known as an intensely shy man who shunned the spotlight, Wagner pulled off the biggest surprise of his life on December 30 when he married Smith in a private ceremony in his childhood parish, St. John Evangelical Lutheran Church in Carnegie, a small coal-mining and steel mill community six miles southwest of Pittsburgh, where Wagner grew up and still lived. The wedding was such a secret that Wagner’s brother Al, who served as best man, found out just hours before the ceremony, after which the newlyweds traveled to the bride’s house to inform her parents. “Honus Wagner Caught at ‘Home’ by Dan Cupid,” reported the Pittsburgh Gazette-Times playfully on the front page the following day, adding confidently, “His retirement from baseball is not yet in sight.”3

While Wagner embarked on a care-free honeymoon vacation in warmer climates in the south and west, Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss brooded. The shrewd German-born businessman, upset about high player salaries coupled with poor results on the field, embarked on a policy of financial retrenchment, as did owners throughout baseball. He slashed contract offers, in some cases by half, and expected holdouts, reported sportswriter Charles J. Doyle of the Gazette-Times, but players had few options and no leverage.4

Among the highest paid players in baseball, earning a reported $10,000 annually, Wagner had his salary reduced significantly, according to Arthur Hittner in his groundbreaking biography Honus Wagner: The Life of Baseball’s “Flying Dutchman,” and might have been slashed to as low as $5,400.5 Ralph S. Davis, a sportswriter with the Pittsburgh Press, attempted to diffuse the growing public perception that Wagner was in a salary dispute with Dreyfuss and had retired, suggesting that Wagner’s reluctance to sign had more to do with his expanding girth (he had gained a reported 20-30 pounds).6

By the first week of February 1917, the great Wagner wait was on. While Pittsburgh sportswriters reported every rumor, Wagner himself remained silent about his future. Wagner “still has a lot of baseball left in him,” said former Pirates skipper Clarke.7 Wagner uncharacteristically stepped into the limelight on February 25 when the Hot Stove Club of Pittsburgh put on a gala celebration for the player’s 43rd birthday at the luxurious William Penn Hotel, where he was roasted by local politicians, industrial magnates, and big-league players. Dreyfuss described his longtime star as a model player and the one “with whom no one ever had any trouble,” according to sportswriter Ed F. Balinger.8 Those laudatory remarks seemed to diffuse, at least momentarily, any sign of a feud between the two kingpins of Pirates baseball and instilled confidence that Wagner would play in 1917.

Wagner was not with the Bucs when they departed on March 9 to Columbus, Georgia, for spring training. “Is Hans dissatisfied in his relations with the Pirates club?” asked beat reporter Harry Keck. “Or is he afraid that he will not be able to finish the season a regular? Does he see the dread shadow of the bench trailing in his wake?”9 Dreyfuss publicly denied that Wagner was a “hold-out” because of a salary dispute but also added that “I do not know what he will do.”10

Questions swirled around not only Wagner’s future, but the entire 1917 baseball season. On April 6, the United States declared war on Germany, thereby expanding the scope of the world war and raising discussions about canceling the season. Baseball commenced as planned, but for the first time since the previous century, Wagner was not on the Pirates’ roster when they opened the season on April 11 in Chicago. “As far as I know,” said Dreyfuss a few days later, Wagner “has quit the game as he told me he thought of doing.”11 While the Pirates played 28 of their first 35 games of the season on the road, sportswriters deliberated if Wagner retired on his own accord or if he was forced out by the miserly Dreyfuss’s contract offer. “Whichever is correct,” declared Davis, “Wagner quit.”12

As Wagner gradually faded from the headlines in May, Balinger dropped a bomb in the Pittsburgh Post on June 3: “Hans Wagner’s baseball days may not be over after all,” began the sportswriter in an article that initiated a frenzied few days.13 Wagner’s return, if it happened, continued the scribe, would be as a coach. Pittsburghers woke four days later to read “Wagner Signs Pirates Contract” emblazoned on the front page of the sports section of the Post.14 The previous evening Wagner had accepted a contract calling for a reported $10,000 salary. Dreyfuss issued a statement suggesting the inevitability of Wagner’s return. “He has been a fixture for so many years that he has come to be almost a part of the club, like the grandstand or the pitcher’s box.”15

Less than a day after signing his contract, Wagner was in uniform as the lowly Pirates, with major league baseball’s worst record (14-27), took on the Brooklyn Robins at Forbes Field on June 7 in front of an “unusually large” crowd [estimated at 4,000] for a midweek game.16 “It was evident that something would have to be done to revive interests,” Davis quipped about the legend’s return to the moribund team.17 Playing first base and batting fifth, Wagner put on a “classy performance” (Balinger) and “played in oldtime style” (Davis), singling in four at-bats and driving in a run, but the Pirates lost yet again.18 Visibly overweight and out-of-shape, Wagner hadn’t trained, let alone played baseball, since ending the 1916 season in a month-long slump; nonetheless, in his fourth game, he took over third base, a position he’d played just 18 times since 1901. After his first eight games in 1917, he had managed nine singles, four of which came in one game, in 33 at-bats, while the Bucs won just twice. It was clear that the Flying Dutchman was no elixir to the Bucs woes.

Wagner’s return for his 21st season was akin to a grand farewell tour. In the first contest of a three-game series in St. Louis, Wagner was “center of attraction for the fans,” opined the Press.19 That was just prelude to “Wagner Day” on June 22, when Pittsburgh celebrated its favorite citizen’s return to baseball by staging a grand fête and 200-car parade with a “distinct military atmosphere,” reflecting the country’s wartime status.20 Hailed as a “national institution through baseball,” Wagner, flanked by mayor Joseph G. Armstrong, passed by immense crowds from Liberty Street and Fifth Avenue to Forbes Field. The festivities were even greater at the ballpark, where Wagner was presented various gifts while an estimated 1,000 soldiers drilled. “Hans Wagner was the hero of one of the most public demonstrations in the history of the diamond,” gushed Balinger.21 The 43-year-old lined an RBI single in his first at-bat in the Bucs’ eventual victory in 10 innings over the Chicago Cubs. Still, Pirates fans had little to cheer other than Wagner, who ended his slump one day after those festivities by pounding out 13 hits in his next 21 at-bats over a five-game stretch to lift his batting average from .236 to .342 on June 28.

By that time, reports circulated that Callahan, on the hot seat for weeks, had been fired and that Wagner would take the reins of the club. Ralph S. Davis attempted to quash those rumors, reminding readers that Wagner had refused the job when Clarke retired. “He is even more determined now that he will not be manager of the Pirates,” wrote Davis, adding that Wagner “is evidently too wise to attempt to bring order out of chaos that exists.”22 Pittsburgh sportswriters seemed concerned about Wagner’s reputation and how it could be tarnished by taking over a club described by Balinger as comprising “considerable inferior material” and by Davis as a “mistfit aggregation of minor leaguers” and “disgruntled” veterans.23

Callahan was removed as manager on June 29, leading to “all sorts of weird guesses” about his successor, wrote Davis.24 The new manager, he reported, was supposedly from “out west” and had “considerable experience.” Among those tossed around by sportswriters as the next manager included Harry Wolverton, the recently fired skipper of the San Francisco Seals, who was supposedly in Pittsburgh to discuss the matter with Dreyfuss; former NL MVP Larry Doyle, captain of the Cubs, who was rumored to have been acquired in a trade for flychaser Max Carey; and even Dreyfuss himself.

Defying expectations of the Smokey City sportswriters, Wagner was named Pirates interim manager the day Callahan was fired. “Just how long Wagner will remain at the helm appears to be indefinite,” wrote Balinger, noting that Wagner “would be afforded ample opportunity to show what he might do in the role of a real pilot.”25 Providing a different perspective, Davis reported that Wagner “requested that he be relieved of the duties as soon as possible. Evidently, the veteran does not care to shoulder the responsibility for a tail end club.”26

Defying expectations of the Smokey City sportswriters, Wagner was named Pirates interim manager the day Callahan was fired. “Just how long Wagner will remain at the helm appears to be indefinite,” wrote Balinger, noting that Wagner “would be afforded ample opportunity to show what he might do in the role of a real pilot.”25 Providing a different perspective, Davis reported that Wagner “requested that he be relieved of the duties as soon as possible. Evidently, the veteran does not care to shoulder the responsibility for a tail end club.”26

While spreading the news about Wagner, Davis offered yet another twist by suggesting that Hugo Bezdek, a “professional friend” of Dreyfuss, might be the hitherto unidentified westerner and yet another managerial candidate. Bezdek was a well-known college football coach who had guided the University of Arkansas to an undefeated season in 1909 and was coming off a Rose Bowl victory as head coach of the University of Oregon. He had also served as head baseball coach at those two institutions and was a Pirates scout on the West Coast. Unimpressed with those credentials, Davis opined that Bezdek “can probably be secured on the cheap.”

On his first day calling the shots for what Davis called “one of the cheapest [teams] in the major leagues and . . . just where it belongs in the standings,” manager Wagner made all the right moves while first baseman Wagner supplied some timely hitting for the last-place Bucs’ 5-4 win against skipper Christy Mathewson’s Cincinnati Reds.27 Wagner led off the second with a double and then scored on Chuck Ward’s two-bagger to tie the game 1-1. In the sixth, Wagner’s two-run single knotted the game 3-3. Wagner’s batting average improved to .354, but declined steadily thereafter.

Notwithstanding his reputation as one of the greatest players in history, Wagner was in an untenable position as both player and interim manager. His return, predicated on Dreyfuss’s acquiescence to his salary demands, fueled dissension among the players, most of whom weren’t in the big leagues during the Flying Dutchman’s heyday. The Pittsburgh Press noted that some players were upset by what they felt was Wagner’s special treatment by Dreyfuss and “became more sullen and discontented than ever, and, instead of helping matters, the situation became worse than ever.”28 To some teammates, Wagner was part of the problem, not a solution.

Fresh off his first, and what proved to be his only, victory as manager, Wagner and the Pirates traveled to Cincinnati for a doubleheader the next day. Wagner “was not forgotten by his thousands of faithful friends at Redland” Field, gushed Queen City sportswriter Jack Ryder about the large crowd, estimated at 18,000 strong, on hand for “Wagner Day” at the park.29 Reds players and officials celebrated the living legend and showered him with gifts in ceremonies before the first and second games. Reds hurler Fred Toney stole the show, however, as he started both games of the twin bill, tossing consecutive complete-game three-hitters. Wagner collected one safety in each contest, extending his hitting streak to nine games.

Accompanying the Pirates on their one-day whirlwind tour to Cincinnati was Dreyfuss, who met with Bezdek, who’d arrived from Oregon. The reason for the meeting was unclear, but to Pittsburgh sportswriters, it appeared as though an intrigue were brewing. Harry Keck of the Post defended Wagner, writing that he “will lose no prestige if he doesn’t improve” the team, and that he doubted Wagner would remain much longer as skipper because he lacks the tough-edged personality needed to discipline the players.30 Ralph S. Davis thought Wagner “appears to be defeated before he starts,” considering the Pirates below-average talent.31

Dreyfuss, Wagner, and Bezdek traveled back to the Smokey City separately from the players. Following the Bucs’ 6-4 loss to the Cardinals at Forbes Field on July 2, details of their meeting emerged. Balinger reported that Wagner and Bezdek “will work together,” with the former in charge of “playing” and the latter taking care of “business affairs” in a potentially awkward responsibility-sharing situation.32 “The team needs much more than a new manager before it will become a menace to the other seven clubs in the league,” wrote the Press.33

On Tuesday evening, July 3, following the Pirates’ fourth straight loss, Wagner resigned from his position as interim manager. “You couldn’t coax him back on the job with a battle ax as a persuader,” joked Davis in the Press.34 The 34-year-old Bezdek was named the new skipper for the rest of the season and was in the dugout as the club hosted the Redbirds for a Fourth of July doubleheader. The Bucs dropped both games, but Wagner, noted Balinger, “played first base without being bothered by the cares and worries of a tail-end ball club.”35

So ended Wagner’s inglorious five-game, four-day career as Pirates skipper. Liberated from a task he never really wanted, Wagner was able to settle into his role as the grand old man of the national pastime and continue his farewell tour. On July 6, the Pirates kicked off an eastern road swing in Philadelphia, where the Phillies celebrated Wagner Day at the Baker Bowl by presenting the player with a leather traveling bag in a pre-game ceremony.36 Six days later, it was the Brooklyn Robins’ turn with Wagner Day at Ebbets Field, where the club’s namesake, skipper Wilbert Robinson, presided over a ceremony at home plate.37

A chance for a fairy-tale ending to Wagner’s illustrious career was abruptly snatched away two days later when he was spiked on the right ankle by the Robins’ Casey Stengel in the second game of a doubleheader in Brooklyn.38 The injury, initially diagnosed as slight, became infected and derailed Wagner’s season. Batting a robust .313 at the time, he had trouble pivoting on the foot and started only 24 more games the rest of the year. He was shelved for Wagner Day at Braves Field in Boston on July 19, but delighted fans the next afternoon at Coogan’s Bluff by pinch-hitting against the New York Giants on yet another Wagner Day, at the Polo Grounds. A hobbling Wagner managed just 3 hits in his final 30 at-bats of the season and batted a paltry .202 (20-for 99) after the spiking.

In an interview with Baseball Magazine in March 1918, Wagner admitted, “I had firmly made up my mind to quit [following the 1916 season]. I was getting old for a player and the end was clearly in sight. . . . But when the season rolled around and the boys began to take their swing and the pitchers started loosening up I couldn’t get over the idea that I would like one more try at it.”39 Wagner had the same thoughts again that spring, but knew better than to try another comeback.

A lifelong Pirates fan, GREGORY H. WOLF was born in Pittsburgh, but now resides in the Chicagoland area with his wife, Margaret, and daughter, Gabriela. A Professor of German and holder of the Dennis and Jean Bauman endowed chair of the Humanities at North Central College in Naperville, Illinois, he is currently the co-director of SABR’s BioProject and has edited seven books for SABR, including those on the 1929 Chicago Cubs (2015), 1957 Milwaukee Braves (2014), 1965 Minnesota Twins (2015), 1979 Pittsburgh Pirates (2016, co-edited with Bill Nowlin), as well as County Stadium (2016) in Milwaukee, the Houston Astrodome (2017), and Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis (2017). He’s written more than 150 biographies of players for the BioProject, and approximately 100 games for the Games Project.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet’s World Wide Web site, Baseball-Reference.com, SABR.org, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record.

Notes

1 Dennis DeValeria and Jeanne Burke DeValeria, Honus Wagner. A Biography (New York: Henry Holt, 1995), 267.

2 Harry Keck, “Sporting Chit Chat,” Pittsburgh Post, June 21, 1917.

3 “Honus Wagner Caught At ‘Home’ by Dan Cupid,” Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, December 31, 1916.

4 Charles J. Doyle, “Carmen Hill Released to Birmingham in Grimes’ Deal,” Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, January 7, 1917.

5 Arthur D. Hittner, Honus Wagner. The Life of Baseball’s “Flying Dutchman,” (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1996).

6 Ralph Davis, “Ralph Davis’ Column,” Pittsburgh Press, February, 5, 1917.

7 “Hans Wagner Praised by His Former Pilot,” Pittsburgh Press, February 11, 1917.

8 Ed F. Balinger, “Wagner Night Howling Success,” Pittsburgh Post, February 25, 1917.

9 Harry Keck, “Sporting Chit-Chat,” Pittsburgh Post, March 13, 1917.

10 “Wagner Not a ‘Hold-Out,’ Says Barney,” Pittsburgh Post, March 16, 1917.

11 “Wagner Has Not Signed A Contract,” Pittsburgh Press, April 15, 1917.

12 “Ralph Davis, “Ralph Davis’ Column,” Pittsburgh Press, April 21, 1917.

13 Ed F. Balinger, “Wagner May Come Back. See Phils Down Bucs. Confers With Callahan,” Pittsburgh Post, June 3, 1917.

14 Ed F. Balinger, “Hans Wagner Signs Pirates Contract,” Pittsburgh Post, June 7, 1917.

15 DeValeria and DeValeria, Honus Wagner, 272.

16 Ralph S. Davis, “Baird Goes To Bench,” Pittsburgh Press, June 8, 1917.

17 Ralph. S. Davis, “Brooklyn-Pittsburgh Ball Game Today Postponed,” Pittsburgh Press, June 6, 1917.

18 Davis, “Baird Goes To Bench.”

19 “Pepper Shown By Pirates,” Pittsburgh Press, June 19, 1917.

20 “Thousands Will Honor Honus Wagner Today,” Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, June 22, 1917.

21 Ed F. Balinger, “Bigbees’s Long Blow and Big Bill’s Rap End Fray in 10th,” Pittsburgh Post, June 23, 1917.

22 Ralph S. Davis, “Dreyfuss Seeking Successor to Jimmie Callahan. Wagner Refuses The Job,” Pittsburgh Press, June 29, 1917.

23 Ed F. Balinger, “New Buccaneer Leader May Succeed Callahan With Next Few Days,” Pittsburgh Post, June 29, 1917; Davis, “Dreyfuss Seeking Successor.”

24 Ralph S. Davis. “Guessing As To Identity of New Buccaneer Manager,” Pittsburgh Press, June 30, 1917.

25 Ed F. Balinger, “Hans Wagner Chosen Pilot of Buccaneers in Callahan’s Place,” Pittsburgh Post, July 1, 1917.

26 Ralph S. Davis, “Honus Wagner In Command,” Pittsburgh Press, July 1, 1917.

27 Davis, “Honus Wagner In Command.”

28 Ralph S. Davis. “Callahan’s Successor in Tough Tome. New Policy Is Needed,” Pittsburgh Press, July 1, 1917.

29 Frank Ryder, “Toney Wins Both Ends of Double-Header,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 2, 1917.

30 Harry Keck, “Sporting Chit Chat,” Pittsburgh Post, July 2, 1917.

31 Ralph S. Davis, “Bezdek Will Not Supplant Wagner Just Now, ‘Honus’ Still On The Job,” Pittsburgh Press, July 2, 1917.

32 Ed F. Balinger, “Hans Wagner Comes First On Pilot Job,” Pittsburgh Post, July 3, 1917.

33 Ralph S. Davis, “Wagner Can’t Make ‘Em Win,” Pittsburgh Press, July 3, 1917.

34 Ralph S. Davis, “Big Job For News Manager,” Pittsburgh Press, July 5, 1917.

35 Ed F. Balinger, “Hans Wagner Resigns And Managerial Reins Are Given To Bezdek,” Pittsburgh Press, July 5, 1917.

36 Jim Nasium, “Phils Lacked Punch When Men Were On,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 7, 1917.

37 Ed F. Balinger, “Dodgers Donate Stein To Wagner, Game To Pirates,” Pittsburgh Post, July 13, 1917.

38 Ed F. Balinger, “Dodgers Again Take Twin Bill Off The Bezdeks,” Pittsburgh Post, July 15, 1917.

39 “Twenty-One Years In The Major Leagues,” Baseball Magazine, March 1918: 395.