The Beginning: Frantic Frankie and Popoff Paul

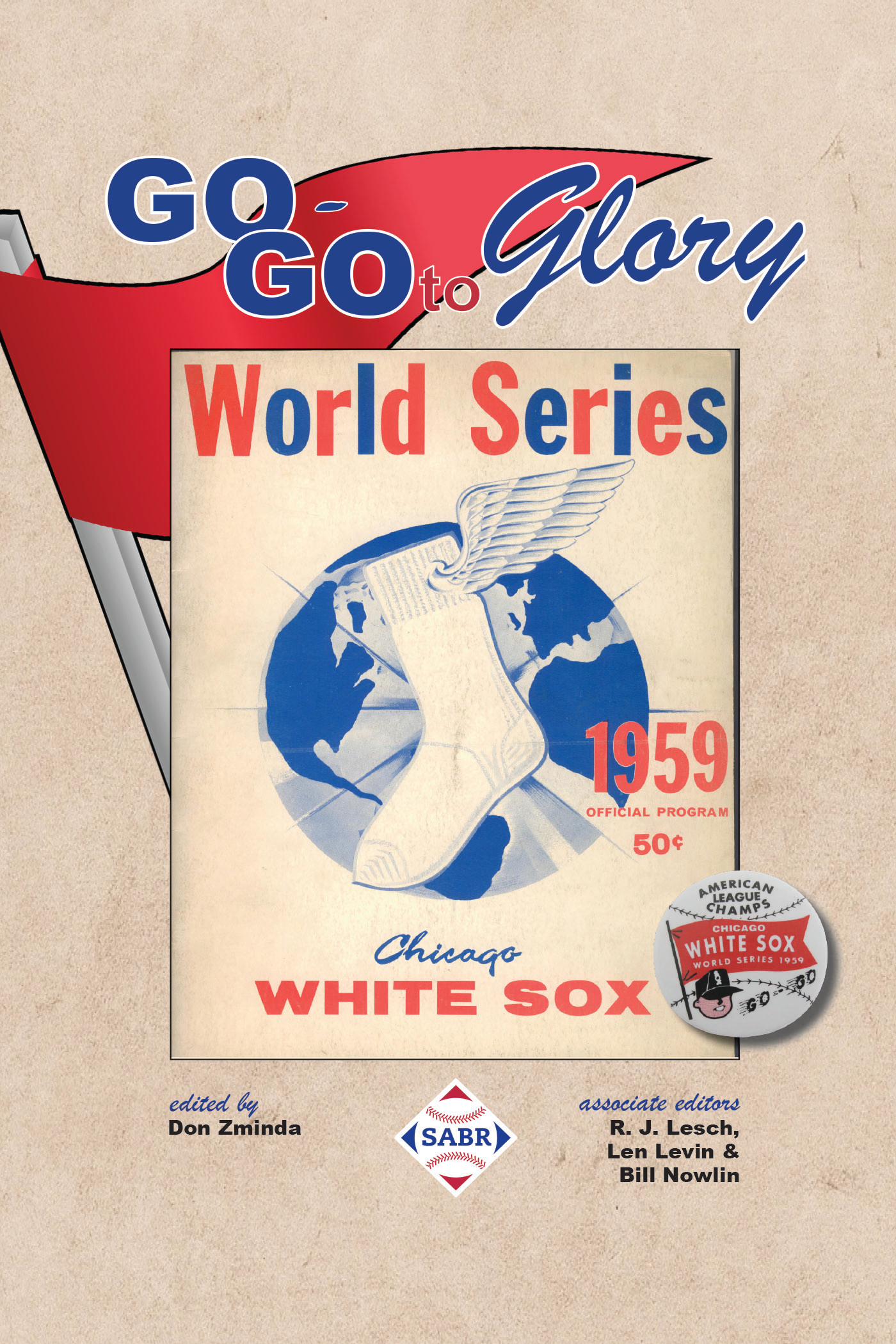

This article appears in SABR’s “Go-Go to Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox” (2019), edited by Don Zminda.

The Go-Go Sox were born on Opening Day at Comiskey Park in 1951, children of a fast-talking general manager and a slow-talking manager.

The Go-Go Sox were born on Opening Day at Comiskey Park in 1951, children of a fast-talking general manager and a slow-talking manager.

After the Black Sox were banned, the White Sox recorded only seven winning seasons in the next 30. They had gone 31 years without a pennant, the longest drought of any big-league club.

The deaths of founder Charles A. Comiskey in 1931 and his son J. Louis in 1939 left the franchise in the hands of Louis’s widow, Grace. She held most of the stock in trust for her three children. Although she served as the team’s president, Mrs. Comiskey spoke up only when it came time to make a decision on spending money. Her usual answer was no.

When her only son, Charles A. Comiskey II, reached his 21st birthday in 1946, he went to work in the White Sox farm system. In 1948 he joined the board of directors as vice president. Young Chuck regarded the team as his birthright. Among his first moves was a critical one that would turn the franchise around.

Comiskey brought in Frank Lane as general manager. Lane grew up in baseball under the volatile Larry MacPhail, working in the Cincinnati Reds and New York Yankees organizations when MacPhail ran those teams. He came to Chicago from the presidency of the Triple-A American Association. A wavy-haired man who favored expensive, tailored suits, Lane was 52 years old and had been lusting for his chance to run a big-league team.

The 1948 White Sox had lost 101 games and finished last. Lane said, “The first thing we have to think about is trades and purchases.”1 He embarked on a trading frenzy. Within two years he acquired a pair of new catchers, Gus Niarhos and Phil Masi, and a new infield: first baseman Eddie Robinson, second baseman Nellie Fox, third baseman Hank Majeski, and shortstop Chico Carrasquel. He added pitchers Billy Pierce, Ray Scarborough, and Bob Cain. Sportswriters nicknamed him Frantic Frankie, but his deals made little difference in the standings. After the Sox lost more than 90 games in both 1949 and 1950, Lane hired Paul Richards to manage the club.

Richards, a lanky 42-year-old Texan, had been a weak-hitting catcher for the Dodgers, Giants, and Athletics. He was still in his 20s when he realized that his future lay in managing. He led the Atlanta Crackers to two Southern Association pennants in five seasons as player-manager, then returned to the majors in 1943 as a wartime replacement player for Detroit. After the war he managed four years in Triple-A, winning an International League pennant for Buffalo.

Richards was a ferocious umpire-baiter who drew comparisons to the Vesuvian John McGraw. International League writers called him Popoff Paul and Ol’ Rant and Rave. He was a Baptist Sunday School teacher who never said anything stronger than “damn” or “hell” at home, but he shocked ballplayers and even hardened umpires with his abusive, obscene tirades on the field.

Most important, Richards was a teacher. He explained to author Donald Honig, “There are an awful lot of small details that add up to the winning of a ball game, and it’s up to the man in charge to see that his players are always drilled in and constantly alert to those things.”2 When his team butchered a play, he would put them back on the field after the game and practice that play “not just eight or ten times, but fifty or a hundred times,” Eddie Robinson said.3 He had earned a reputation as a master teacher of pitchers. His most famous pupil was the Tigers’ Hal Newhouser, a wild, hot-tempered young left-hander who blossomed into a two-time Most Valuable Player and four-time 20-game winner under Richards’ tutelage.

Many managers believe pitching and defense are keys to a winning team. For Richards, that was a religion, not just a strategy. He told Chicago writers, “The most important thing to me is to get the other fellow out. Almost every game is decided by the loser giving it away rather than the winner winning it. A good defense, inclusive of pitching, is the most vital part of a successful team.”4

Richards had little to say to the writers, or to his players. Many of the Sox echoed infielder Joe DeMaestri’s description: “No conversation. No words of encouragement. Seldom a smile. He never got close to his players. But in a game he was always two, three innings ahead, like he knew what was going to happen.”5

The team Richards inherited had just four decent players. Twenty-four-year-old lefthander Billy Pierce, who had pitched for Richards in Buffalo, held opposing hitters to a .228 average in 1950, second lowest in the league, but walked more men than he struck out. Eddie Robinson contributed 20 home runs after being acquired from Washington. Chico Carrasquel, purchased from the Dodgers, was a slick shortstop who batted .282 as a rookie. Gus Zernial set a team record with 29 homers, but also led the majors in strikeouts and was a liability in the outfield.

Richards and Lane overhauled the pitching staff, trading journeymen Ray Scarborough and Bill Wight to Boston for veteran Joe Dobson and a .300-hitting outfielder, Al Zarilla. They drafted right-hander Harry Dorish from the minors; he would become the team’s top reliever. Another of Richards’ makeover projects, right-hander Saul Rogovin, came from Detroit. He had enjoyed his only success under Richards at Buffalo.

Before spring training Richards declared second base “our weakest spot.”6 The tiny incumbent, Nellie Fox, had posted a .608 on-base plus slugging percentage with just 19 extra-base hits. Richards assigned coach Doc Cramer to turn the 23-year-old into a hitter and brought in the recently retired all-star second baseman Joe Gordon to teach him to turn the double play. After many hours of extra batting practice and thousands of groundballs, Fox won the manager over with his grit. “We just gave him a chance, that’s all,” Richards said. “He took it.”7

Beginning the season in St. Louis, the White Sox battered the Browns for 19 hits in a 17-3 victory. Three days later they opened at home against Detroit. Rookie center fielder Jim Busby singled in the fourth inning, then stole second and third on consecutive pitches. Richards, coaching at third, told him, “Well, regardless of what happens, Jim, you’ve got to go home on this next pitch.” The manager put on a suicide squeeze. The batter, pitcher Randy Gumpert, laid it down and Busby raced across the plate. Years later Richards recalled, “That was the birth of the Go-Go Sox.”8 Fans began chanting “Go! Go!” whenever a player reached base.

By mid-May the Sox had stolen 20 bases, more than in the entire previous season. With home run totals rising, few teams were running; the stolen base was a surprise play. The Sox finished with 99 steals, the most in the AL since the war, and led the league for the next 10 years. “We’ve been getting as much benefit from our reputation as a running team as from actual running,” Richards said. “Sometimes it’s better to have one of your speed men not run, but stay on first base and upset the pitcher rather than go to second.”9

The season was two weeks old when Lane pulled off the best trade of his hyperactive career. After 20 hours on the telephone, he swung a three-way deal that brought rookie Orestes Minoso from Cleveland. Minoso had batted .339 in the Pacific Coast League in 1950, with 70 extra-base hits and 30 steals. Richards, who had watched him while managing Seattle, wanted him badly, but Lane protested that Minoso was a poor outfielder and a worse third baseman. Richards replied, “I’ll find a place for him. …We’ll just let him hit and run.”10 Minoso was a black Cuban; the White Sox were only the third American League team to integrate. He homered in his first time at bat for Chicago and quickly became the engine of the Go-Go Sox.

The White Sox gave up their leading power threat, Gus Zernial, in the Minoso deal. Richards was building his offense around speedy line-drive hitters. “That’s the only way you can win at Comiskey Park,” he said. “You’re beating your head against a stone wall by trying to pack a lineup with long-ball hitters. With the long fences we have [352 feet down each foul line] and the wind constantly blowing in, a home run hitter is severely handicapped. He just hits long flies that are easy outs.”11

Richards pulled another trick out of his bag – his most famous one – in a May 15 game at Boston. With Ted Williams due to lead off the ninth, Richards moved right-handed pitcher Harry Dorish to third base and brought in lefty Pierce to face the left-handed slugger. After Pierce got Williams to pop out, Dorish returned to the mound. Veterans of the American League’s first season – including Connie Mack and Cy Young – were on hand to celebrate the league’s 50th anniversary. None of them could remember seeing such a pitcher switch.

Chicago won the game on Nellie Fox’s 11th-inning homer, the first of his career after 804 at-bats. It was the beginning of a 14-game winning streak that lifted the club to first place. An Associated Press reporter wrote that the White Sox had gone “from rags to Richards.”12

A rare epidemic struck the South Side of Chicago: pennant fever. A June series against the Yankees drew 130,720 fans over three days, a franchise record. The national press took notice, too. Life magazine published a five-page photo spread on the “White Hot” Sox. The Saturday Evening Post profiled the manager in a piece titled “He Put the White Sox Back in the League.”

By the time the Post dubbed them “the darlings of baseball,” the Sox had begun to droop.13 Locked in a tight four-way race with the Yankees, Indians and Red Sox, they barely stayed above .500 in June, then fell to 11-21 in July. They lost the lead for good on July 14. But a fourth-place finish and 81-73 record gave the club its first winning season since 1943. The fans kept coming – more than 1.3 million of them, the first time the franchise had topped 1 million in its 51-year history.

The makeshift pitching staff allowed the third-fewest runs in the league. Saul Rogovin, fresh off the scrap heap, led the league in ERA; Pierce was fourth. The young lefty cut his walks in half.

Minoso and Fox emerged as stars. Minoso led the league with 31 stolen bases and his .922 OPS was third best. Fox batted .313 while striking out only 11 times in 681 plate appearances. They became two of the most popular players ever to wear the White Sox uniform, captivating fans with their all-out hustling style.

Richards and Lane moved the White Sox up to third place for the next three seasons, but they could not catch the powerful Yankees and Indians. Chicago writer John P. Carmichael said they “often thought as one man.”14 While Lane made the deals, many of the players he acquired were Richards’ choices.

By the time Richards left in 1954 and Lane was forced out by the Comiskeys a year later, they had resurrected the moribund franchise. They built the foundation for 17 straight winning seasons and the team’s first pennant since the Black Sox.

WARREN CORBETT is the author of The Wizard of Waxahachie: Paul Richards and the End of Baseball as We Knew It and a past winner of the McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award. He is a beach bum at Pawleys Island, South Carolina.

Sources

This article is adapted from The Wizard of Waxahachie: Paul Richards and the End of Baseball as We Knew It, by Warren Corbett (Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 2009).

Notes

1 The Sporting News, October 20, 1948: 22.

2 Donald Honig, The Man in the Dugout (Chicago: Follett, 1977), 142.

3 Eddie Robinson, interview by the author, August 18, 2006, Fort Worth, Texas.

4 The Sporting News, October 25, 1950: 1, 4.

5 Norman L. Macht, “Turn Back the Clock: Memories from Former Shortstop Joe DeMaestri,” Baseball Digest, September 2003, 77.

6 Neal R. Gazel, “Nellie Does Right by the White Sox,” Baseball Digest, August 1950: 5.

7 David Gough and Jim Bard, Little Nel: The Nellie Fox Story (Alexandria, Virginia: D.L. Megbeck Publishing, 2000), 76.

8 Paul Richards, interview by Clark Nealon, February 5, 1981. In the collection of the Texas Sports Hall of Fame, Waco.

9 Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1951: C5.

10 Jerome Holtzman and George Vass, Baseball Chicago Style (Chicago: Bonus Books, 2001), 102.

11 The Sporting News, May 9, 1951: 7.

12 Associated Press-Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail, June 19, 1951: 11.

13 William Barry Furlong and Fred Russell, “He Put the White Sox Back in the League,” Saturday Evening Post, July 21, 1951: 91.

14 The Sporting News, November 10, 1951: 11.