Birmingham, Pittsburgh, and the Negro Leagues Since 1948

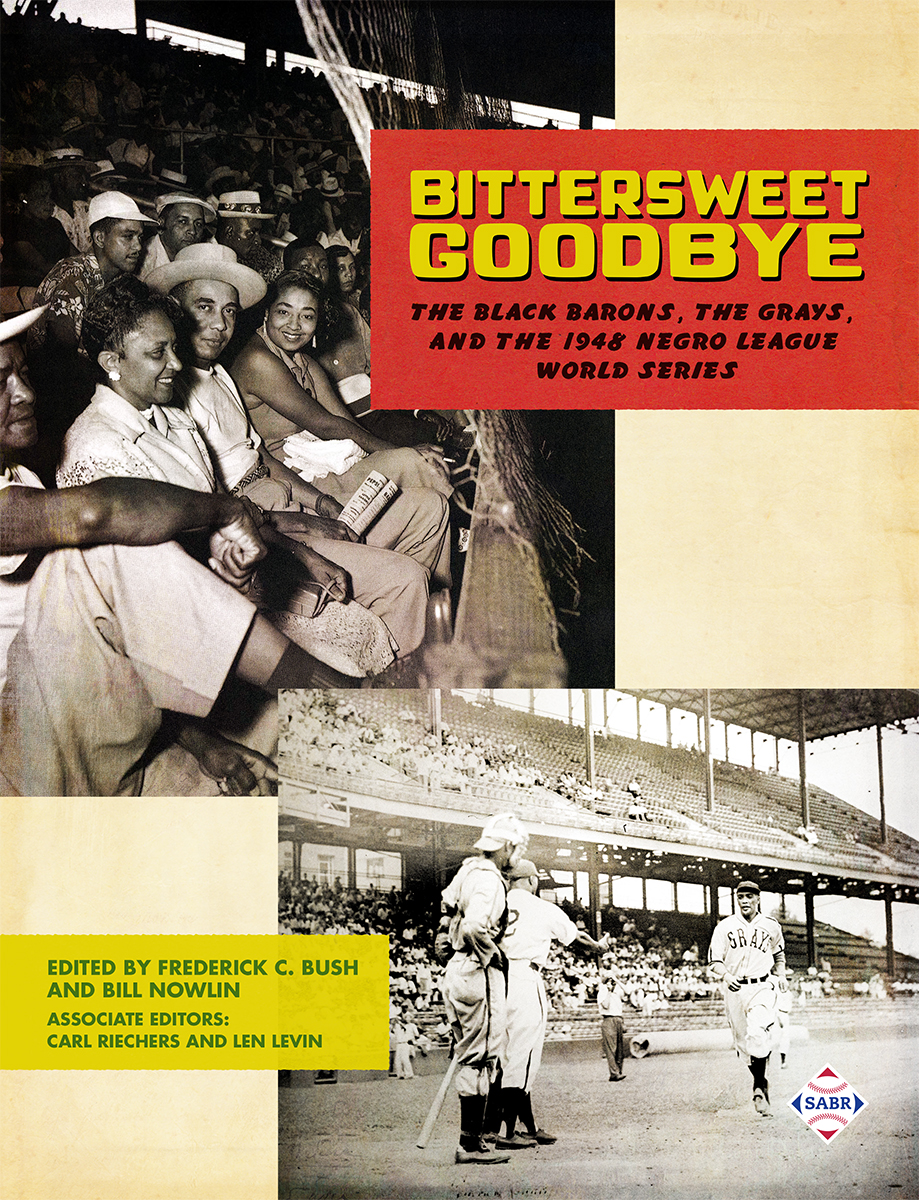

This article appears in SABR’s “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

To people familiar with the historical relationship between the cities of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Birmingham, Alabama, it must seem appropriate that the last Negro League World Series, in 1948, was played between teams from those two areas – the Homestead Grays and the Birmingham Black Barons – and inevitable that the Grays would emerge as the victors.1 Though founded in different centuries (Pittsburgh in 1758 and Birmingham in 1871) and located in different parts of the country, the two cities became powerhouses of their regions as a result of their steel industries and nearby coal-rich areas. In time, Birmingham became the leading manufacturer of foundry iron in the United States, earning the nickname “The Pittsburgh of the South.”2

To people familiar with the historical relationship between the cities of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Birmingham, Alabama, it must seem appropriate that the last Negro League World Series, in 1948, was played between teams from those two areas – the Homestead Grays and the Birmingham Black Barons – and inevitable that the Grays would emerge as the victors.1 Though founded in different centuries (Pittsburgh in 1758 and Birmingham in 1871) and located in different parts of the country, the two cities became powerhouses of their regions as a result of their steel industries and nearby coal-rich areas. In time, Birmingham became the leading manufacturer of foundry iron in the United States, earning the nickname “The Pittsburgh of the South.”2

In 1907, however, Pittsburgh’s US Steel Corporation bought out Birmingham’s Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company, its largest competitor at that time, in a move that ensured that Pittsburgh would remain the country’s leader in the steel industry. When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, US Steel “started shutting down the mills [in Birmingham] to protect its interests in the North.”3 The effect on Birmingham’s economy was so severe that “[t]he city government was on the verge of shutting down by mid-1933” and it took a loan from the First National Bank to keep “the city machinery from grinding to a halt.”4 Birmingham eventually rose from the ashes, but it was clear that there would be only one Pittsburgh in the United States. Toward the end of the twentieth century, Birmingham journalist Paul Hemphill observed, “[V]irtually no new industry, blue-collar or otherwise, had filled in the gap, mainly because U.S. Steel and the local barons didn’t want the competition.”5

In 1948 US Steel still had an open-hearth works facility operating in Homestead, so many of the Grays lived in the shadow of the mills. The same was true for many Black Barons players, who had graduated to the club from Birmingham’s industrial leagues. Thus, the competition between the two baseball clubs mirrored the competition between the two cities’ primary industry. The teams already had competed for the championship of Negro baseball in both 1943 – a hard-fought series won four games to three by the Grays – and 1944, when the Grays needed only five games to prevail. However, by the time of the 1948 Negro League World Series – the third clash in six years between the two teams – the handwriting was on the wall for the demise of the Negro Leagues.

After Jackie Robinson’s debut at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947, Organized Baseball began to pursue the Negro Leagues’ top talents. The result was a rapid decline in the quality of Negro baseball and, as was to be expected, a turning of black fans’ attention away from the Negro Leagues and toward the black players who were now taking the field for major-league teams. In 1948 center fielder Larry Doby and pitching legend Satchel Paige helped lead the Cleveland Indians to the World Series title over the Boston Braves, making the Indians franchise the first integrated professional sports team in America to win a championship. Even the black press now devoted most of its attention to the major-league World Series, due to Doby’s and Paige’s involvement, and included only brief write-ups and line scores (rather than box scores) in its meager coverage of the championship clash between the Grays and the Black Barons.

The integration of Organized Baseball brought hope to those black players who believed they were destined for major-league stardom (including Birmingham’s Willie Mays) and sadness to others who knew that they would either toil in obscurity for low wages or have to leave baseball altogether. Birmingham’s Bill Greason, the winning pitcher in the Black Barons’ lone victory over the Grays in the 1948 series, summed up the bittersweet feelings of many Negro Leaguers when he said:

“There was a little bit of sadness on the Black Barons that season. We could all sense that something was leaving the game, and a lot of the players who were honest knew that the Negro League wouldn’t survive much longer. But Willie [Mays] made us [Black Barons] remember in every game he played why we wanted to play baseball so much in the first place.”6

Greason’s sense of impending doom about the end of the Negro Leagues began to become reality when, shortly after his Black Barons fell to the Grays, the Negro National League, to which Homestead belonged, disbanded. In the absence of competing leagues, it was obvious that no further Negro Leagues World Series would be played.

In spite of Organized Baseball’s raid of the best players in black baseball, the full integration of the major leagues did not occur overnight. Initially, an unwritten “two black players per team” quota system was in place for most clubs, and it took until 1959 – 12 years after Robinson’s debut – for every major-league team to have employed at least one black player when the Boston Red Sox added Elijah “Pumpsie” Green to their roster. For every Willie Mays, Henry Aaron, or Ernie Banks who emerged from the remnants of the Negro Leagues into major-league stardom, there were dozens of others who never received a chance equal to that of their white counterparts or who simply were not good enough to make it to the big leagues.

In 1966 Red Sox legend Ted Williams brought attention to the defunct Negro Leagues by using his Hall of Fame induction speech to advocate the inclusion of former Negro League players in baseball’s shrine of the immortals. Williams remarked on the fact that Willie Mays had just surpassed him in career home runs, and added, “I hope that one day Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson will be voted into the Hall of Fame as symbols of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given the chance.”7 Nevertheless, as had been the case with the integration of the sport itself, the integration of its most hallowed halls was a slow process.

In 1969 Bowie Kuhn became the commissioner of baseball, and he appointed a 10-man committee to nominate former Negro League players for induction into the Hall of Fame. As a result, in 1971, Satchel Paige became the first player who had spent the majority of his career in the Negro Leagues to enter the Hall of Fame; many future Negro League inductees would be players who had spent their entire careers in black baseball. However, when Kuhn made the announcement of Paige’s election in February 1971, he indicated that Paige would be enshrined in a new Negro wing of the Hall, prompting such an outrage that a once-segregated player would now be a segregated immortal that the idea for a separate wing for Negro Leaguers was scrapped and Paige’s bust took its place among those of his baseball peers in Cooperstown, New York, in July of that year.

During the course of the 1970s, baseball historians Robert Peterson and John Holway pioneered Negro League research, but there still appeared to be little interest among most fans and students of the game. Major- and minor-league cities also tended to ignore their former Negro League counterparts. Eventually – on September 11, 1988 – the Pittsburgh Pirates became the first franchise to honor its city’s Negro League clubs, the Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords. Before that evening’s game, a flag commemorating the Grays’ 1948 championship was raised to fly alongside the Pirates’ own championship banners at Three Rivers Stadium. Four members of the 1948 Grays – Clarence Bruce, Buck Leonard, Willie Pope, and Bob Thurman – and six other Negro Leaguers were honored that night. Bruce, speaking at the ceremony, pointed to the Grays’ pennant banner and proclaimed, “That means the Grays are a legend. That means we haven’t been forgotten.”8

Two years later, in 1990, the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum was founded in Kansas City, Missouri, by local business leaders, historians, and baseball players. In 1997 the museum moved to its current location at 18th and Vine Streets, a historic African-American district, which it shares with the American Jazz Museum. Visitors to the museum “experience a tour of multi-media displays, museum store, hundreds of photographs, and artifacts dating from the late 1800s through the 1960s.”9

In his 2007 book The Soul of Baseball, a Kansas City Star columnist, Joe Posnanski, documented a year he had spent traveling with legendary Kansas City Monarchs player-manager Buck O’Neil, the driving force behind the founding of the museum. Former 1948 Black Baron turned Hall of Fame immortal Willie Mays came to visit the museum one day, but his glaucoma-ravaged eyes would not allow him to step under the bright lights of the centerpiece Field of Legends display. Mays told O’Neil, “You know I really don’t need to see the museum. I lived it.” However, Mays had already seen many of the displays, and they had made such an immense impact that a close friend later phoned O’Neil to tell him that Mays “[had] cried the entire ride back to the hotel.”10

In addition to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, the rediscovery and commemoration of the Negro Leagues were given further impetus by the publication of two landmark books in 1994: James A. Riley’s The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, which provided brief biographical sketches of as many players as Riley could uncover, and Dick Clark and Larry Lester’s The Negro Leagues Book, which compiled rosters and player statistics and examined the greatest teams and Hall of Famers from black baseball.

Since the mid-1990s, there has been an explosion in research and literature about the Negro Leagues as well as their role in the integration of major-league baseball. Twenty former Negro Leaguers were inducted into the Hall of Fame from 1971 to 1999. The surge of interest in black baseball has brought more attention to its players and has aided in the enshrinement of an additional 15 Negro League players since the turn of the twenty-first century.11 There were more than 35 Hall of Fame-caliber players in over a half-century of Negro League baseball, of course, though it remains to be seen how many additional players will be selected for induction at Cooperstown.

In 1997 Jackie Robinson’s number 42 was universally retired by every major-league team, though the number is worn today by every major leaguer in games played on April 15 – Jackie Robinson Day – to commemorate Robinson’s first game with the Dodgers. Many major- and minor-league teams throughout the country now also honor their respective city’s black baseball heritage, with players often donning throwback uniforms of bygone Negro League teams for one game each year.

In light of America’s racial past, however, even attempts to honor the Negro Leagues can sometimes open old wounds or go awry. The Pittsburgh Pirates, the very club to first acknowledge the Negro Leagues, created a display area named Highmark Legacy Square at their current stadium, PNC Park, in 2006. A press release on the team’s website stated:

“The exhibit features life-size bronze statues of former Negro Leagues greats Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, Josh Gibson, Judy Johnson, Buck Leonard, Satchel Paige, and Smokey Joe Williams. Each statue is accompanied by an interactive kiosk allowing fans to view a personal video and learn about the player’s background, Hall of Fame honors, and playing statistics.”12

In spring of 2015, as the Pirates were experiencing a new era of success, they decided to strip Highmark Legacy Square of its statues in order to accommodate the larger number of fans attending their games. Sean Gibson, president of the Josh Gibson Foundation, which is named after his great-grandfather, suggested relocating the statues to different areas throughout the stadium, but the Pirates decided simply to rid themselves of them, though they did agree to donate them to Gibson’s foundation.13

The result of the move proved a disaster for the club, which was lambasted by one historian who wrote:

“The Pirates are effectively saying that the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays have nothing to do with the Pirates anymore, and if you want the Crawfords or Grays – or Black history in general – then go to the Forbes Field landmark, the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum, or the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.”14

While the Pirates have taken a step backward, other franchises and cities continue to move forward with tributes to the Negro Leagues.

Most notably, Birmingham – once the most segregated city in the United States and a center of civil rights activism and violence – opened the Negro Southern League Museum in partnership with the Center for Negro League Baseball Research in the summer of 2015. Clayton Sherrod, who has organized reunions of surviving Negro League players at Birmingham’s renovated Rickwood Field, believes the museum to be important “not only because of the Negro Leagues but also because of the industrial leagues, which were huge in Birmingham.”15

Though the founding of the Birmingham museum was a positive development, there was concern on the part of the Kansas City museum that the two entities would compete for the same audience, thus turning the Negro Leagues into a house divided. Dr. Larry Powell, author of Black Barons of Birmingham: The South’s Greatest Negro League Team and Its Players and a professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, attempted to assuage such fears, saying, “This one [Negro Southern League Museum] doesn’t have to be a national museum [as he believes the Kansas City museum has tried to be], but it does need to be a regional museum, one that will attract people from the South.”16

The Negro Leagues, which would not have had to exist had it not been for Jim Crow, remain an example of African-American entrepreneurship under segregation and were a source of great pride for the black community. The late A. Bartlett Giamatti had been elected commissioner of baseball one week prior to the Pirates’ 40-year commemoration of the Grays’ championship in 1988. In commenting on the Pittsburgh ceremony, Giamatti pointed out the importance of the Negro Leagues when he stated, “We must never lose sight of our history, insofar as it is ugly, never to repeat it, and insofar as it is glorious, to cherish it.”17

FREDERICK C. (RICK) BUSH teaches English full-time at Wharton County Junior College in Sugar Land, Texas. Rick has written articles and biographies for numerous SABR books and the SABR website and was also an associate editor for SABR’s book about his hometown team, Dome Sweet Dome: History and Highlights from 35 Years of the Houston Astrodome. He and his wife Michelle, and their three sons live in the northwest Houston suburb of Cypress, Texas.

Notes

1 Homestead is seven miles southeast of downtown Pittsburgh.

2 Christopher Fullerton, Every Other Sunday (Birmingham: R. Boozer Press, 1999), 27.

3 Allen Barra, Rickwood Field: A Century in America’s Oldest Ballpark (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2010), 115.

4 Ibid.

5 Paul Hemphill, Leaving Birmingham: Notes of a Native Son (New York: Viking Penguin, 1993), 114.

6 Barra, 156.

7 Paul Dickson, “Celebrating Ted Williams’ Historic Call for Inclusion 50 Years Ago This Week,” thenationalpastimemuseum.com/article/celebrating-ted-williams-s-historic-call-inclusion-50-years-ago-week, accessed January 6, 2017.

8 “Clarence Bruce, Was Homestead Grays Player” [obituary], Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, January 25, 1990.

10 Joe Posnanski, The Soul of Baseball: A Road Trip through Buck O’Neil’s America (New York: William Morrow, 2007), 34.

11 As of January 2017.

12 Pirates Media Relations, “Pirates unveil Highmark Legacy Square at PNC Park,” pittsburgh.pirates.mlb.com/news/press_releases/press_release.jsp?ymd=20060626&content_id=1523995&vkey=pr_pit&fext=.jsp&c_id=pit, accessed January 7, 2017.

13 Josh Howard, “Disappointment in Pittsburgh: How the Pirates Ditched Pittsburgh’s Negro Leagues Past,” ussporthistory.com/2015/10/12/2902/, accessed January 7, 2017.

14 Ibid.

15 Nick Patterson, “Reclaiming History: More Than a Game, Baseball – Especially the Negro Leagues – Plays a Big Part in Birmingham’s Past and Future,” weldbham.com/blog/2015/02/03/reclaiming-history-birmingham-black-barons/, accessed January 7, 2017.

16 Ibid.

17 Doron P. Levin, “Pittsburgh Recalls a Neglected Title,” New York Times, September 12, 1988: C3.