Hal Lanier

“If you can’t get fundamentals down for Hal Lanier, you cannot play for Hal Lanier,” declared the native Floridian about his managerial philosophy, nearly a half-century since his professional baseball début in 1961.1 Lanier’s emphasis on the foundations of baseball characterized his longevity as a helmsman and, for 10 seasons, a major league ballplayer.

“If you can’t get fundamentals down for Hal Lanier, you cannot play for Hal Lanier,” declared the native Floridian about his managerial philosophy, nearly a half-century since his professional baseball début in 1961.1 Lanier’s emphasis on the foundations of baseball characterized his longevity as a helmsman and, for 10 seasons, a major league ballplayer.

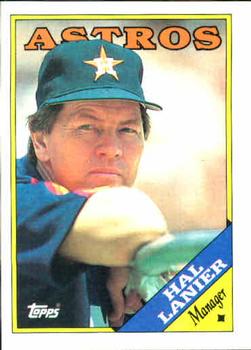

To Houstonians, Lanier, whose MLB playing tenure lasted from 1964 to 1973, is celebrated as the manager guiding the Astros to the 1986 NL West title. With starting pitchers tallying a combined 59 victories and a relief pitcher adding another 11, the Astros ended the season with a 96-66 record.

Houstonians, in particular, needed a reason to celebrate. Badly. NASA’s Johnson Space Center, the Houston site known worldwide as an emblem of space progress, became the focus of the world’s heartbreak when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded on January 28th, killing all seven crew members, including Christa McAuliffe — a civilian teacher. A similar dynamic occurred when the Astros won the 2017 World Series after Hurricane Harvey bashed Houston.

Harold Clifton Lanier belongs to a rare group — a cluster of second-generation major leaguers; his father, Max Lanier, compiled a 108-82 record pitching for the St. Louis Cardinals (1938-46, 1949-51); New York Giants (1952-53); and St. Louis Browns (1953). The elder Lanier had been a pioneer — he fought against baseball’s reserve clause by going south to the Mexican League in 1946 for a five-year contract at nearly twice his $10,500 salary with the ‘46 Cardinals. More than a dozen ballplayers across the major leagues decamped for the Mexican League. But things weren’t quite as rosy as he expected. The condition of the league’s playing fields was wretched, the team owners balked at paying for better ones, and MLB Commissioner Happy Chandler headed off a possible return with a five-year ban on Max and his cohorts. Danny Gardella sued in federal court. The Second Court of Appeals revived the suit after a trial court dismissed Gardella’s case. MLB settled, but faced another suit, this one by Lanier. Cardinals owner Fred Saigh was on his side, so he fought to get Lanier back to major-league status. In turn, Lanier abandoned the legal action.2

Born on July 4, 1942, Lanier was the third of three children. When he was six years old, his mother — Lillian Bell (Doby) — died in a car accident on Christmas Eve, 1948. His father remarried and had two more children.

During his formative years, Lanier’s family traveled to see Max play. So, trips posed little, if any, excitement when Lanier played for the Junior Majors as a teenager in St. Petersburg.

Regarding the team’s journey to Pensacola, Lanier recalled, “I liked the trip because of the game but the travel itself didn’t give me the kick it gave the other kids. I guess I had already been around.”3

A standout athlete at Boca Ciega High School in St. Petersburg, Lanier earned All-City, All-County, and All-State honors in basketball and baseball. His 33 points-per-game led to 54 college basketball scholarship offers. Meanwhile, on the baseball diamond, he hit .407 and went 26-7 as a pitcher in his last two years — including two no-hitters (one a perfect game).4

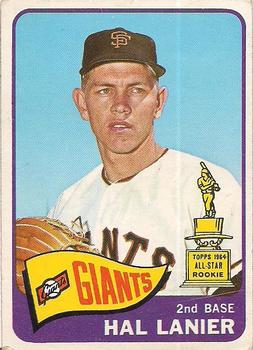

Sacrificing the green grass of a college campus for that of a ballpark, infielder Lanier joined the San Francisco Giants organization for a reported $90,000. He had a highly significant rookie year with the Quincy (IL) Giants in the Midwest League (Class D) in 1961 — playing in 73 games, hitting .315, with a .748 in OPS.

The following season with the Fresno Giants in the California League (Class C), Lanier appeared in 133 games, slashed .351/.389/.741 with 32 walks and 17 stolen bases. double-A, the Springfield (MA) Giants in the Eastern League, for 1963. He proved it to be a wise decision — .282 batting average, 33 walks, 138 games. After 64 games in 1964 with the Tacoma Giants in the AAA Pacific Coast League, where he hit .327, Lanier went to San Francisco. Press reports indicate that Lanier pere and fils signed together for “about $50,000” — Hal as a player, Max as a scout. When Hal signed his initial deal, he got a reported $75,000 bonus.5

Lanier’s connection to baseball was as much a product of nurture as nature. “I grew up around baseball because I was always with my father,” he said upon taking the Houston job. “I think that made me a little better player than my friends because my father taught me at an early age the right way to play. He never pushed me, but he was always willing to help me when I wanted it. I always appreciated that.”6

Lanier’s first game for the parent ball club was on June 18, 1964, against the St. Louis Cardinals. “I was a little nervous at first so it was good to get that first hit,” said Lanier, who went 1-for-3 and scored a run in the Giants’ 7-6 loss; in the four-game series against St. Louis, Lanier notched his first home run in the major leagues, scored four runs, knocked in six runs, and went 8-for-17. Three of his hits were doubles. “The kid has more range at second base than any Giant I’ve seen since Burgess Whitehead,” declared veteran Giants radio announcer Russ Hodges. “More than Eddie Stanky, more than Davey Williams.”7

Giants manager Alvin Dark also saw Lanier’s potential as a second baseman, though the 6’2, 180-pound prospect began as a shortstop. Dark believed that Fresno would allow Lanier to hone his skills. “I’m not worried about Lanier at all,” he said. “We know what he can do and I think he’ll fit right in. I expect him to handle the double play well with [shortstop Jose] Pagan.” Dark also foresaw that Lanier could be a threat at the plate: “He’s an ideal second hitter. He moves the ball around to all fields. He doesn’t try to murder it.” Coach Cookie Lavagetto agreed, “What do I think of Lanier? He’s sensational. That’s the only word for it.”8

On defense, Lanier believed that his height gave him an advantage: “I can get to balls to my left faster because of my height and reach. And I think I cover more ground than I would if I were shorter.”9

Lanier had a decent rookie season in 1964, hitting .274 in 98 games. During spring training the next year, Lanier underscored that his family name did not influence his place on the Giants’ squad. “[T]hat really isn’t so,” he said. “What they don’t know was when I signed with the Giants he wasn’t in baseball. Part of my deal with the Giants was that they would hire him as a scout.” He also reflected on his progress: “I’ve looked bad on slow balls hit to my right. My trouble has been that after fielding ‘em, I came up too high to make the throw in time. This spring, I’m working hard at throwing from a lower level, from a stopping posture.”10

Despite having the power of Willie Mays and Willie McCovey, Giants manager Herman Franks noted at the beginning of the 1965 season that the team scored two or fewer runs 59 times in 1964. Lanier exemplified team spirit, valuing teamwork over personal glory: “I’m not reluctant to give myself up and hit behind a runner if it means advancing a man into scoring position. You play this game to score runs. Nothing else counts.”11

Lanier was an attentive ballplayer proving that baseball is a mental game as well as a physical one. In a September game against the Milwaukee Braves, for example, he demonstrated his base running skills. After reaching base with a single, Jim Davenport followed with a bunt. Braves first baseman Joe Torre gambled that the ball would roll foul. It didn’t. Frustrated, Torre “slammed the ball to the ground” and it “bounced away.” Lanier, meanwhile, had never stopped running. “There was nobody covering home. [Braves catcher Gene] Oliver was between first and home looking down the line when I headed home,” he explained.12

Playing in all but three games in 1965, Lanier batted .226 with 15 doubles and 39 RBI.

1966 was nearly a mirror — .231, 14 doubles, 37 RBI in 149 games. Senior team captain Mays appointed Lanier as another captain. “We didn’t have a very talkative infield,” Willie explained, “and I knew we should have somebody up there who could take charge and run things, such as detecting when a pitcher is faltering, or working too fast, and then going to the mound and doing something about it.”13

Mays tutored Lanier in field management, for example, noting the keys in “how to command and be respected.” Opponents were scrutinized for tells that could when deciphered inform the captains of weaknesses. “I have learned how to detect the signs of approaching fatigue in a pitcher and what to do about it,” Lanier said. “I have studied and learned the habits and idiosyncrasies of opposing batters and I know I’m going to play them batter this year.”14

In 1967, with the Vietnam War raging, Lanier got a call from his draft board for a physical exam. He wasn’t drafted, so he continued as a nearly omnipresent member of the Giants’ lineup — 151 games. In the field, Lanier adjusted his strategy. “I’m going to play closer to second base this year, so I won’t have to run so hard to get there for the double play,” explained Lanier. “I’ll cheat a little. You know, play a few steps closer to the bag and closer to the batter.” By this time, it was evident that Lanier’s greatest value was on defense — from 1965-67, his fielding percentage averaged .980.15 His 1967 batting average was .213.

In 1967, with the Vietnam War raging, Lanier got a call from his draft board for a physical exam. He wasn’t drafted, so he continued as a nearly omnipresent member of the Giants’ lineup — 151 games. In the field, Lanier adjusted his strategy. “I’m going to play closer to second base this year, so I won’t have to run so hard to get there for the double play,” explained Lanier. “I’ll cheat a little. You know, play a few steps closer to the bag and closer to the batter.” By this time, it was evident that Lanier’s greatest value was on defense — from 1965-67, his fielding percentage averaged .980.15 His 1967 batting average was .213.

With Lanier at shortstop and Ron Hunt at second base, the Giants had a very capable double-play combination. “It is because Hal and I have a healthy rapport with each other,” Hunt explained. “We’ve worked hard together, and we’ve learned together. We’re not afraid to get on each other when things go wrong. He’s not reluctant to tell me when I’ve goofed and I’m not backward in telling him a few things he’s done wrong.” Lanier was involved in 72 double plays that year.16

Baseball’s expansion in 1969 with the San Diego Padres and the Montreal Expos forced the Giants to consider putting Lanier in the expansion draft. He had become a regular in the Giants lineup and, even though he only batted .206 in ’68, was valuable on defense. “Nature had designed him to play defense, not to drive fast balls 430 feet,” observed Wells Twombly of the San Francisco Examiner in 1970.17

Lanier’s playing time remained steady: 151 games in 1968; 150 games in 1969. He played in fewer games in 1970 — 134. And after that season, Lanier got word that the Giants might be replacing him. He addressed this subject with honesty and humility:

What I’ve been reading and hearing all winter is that the Giants don’t want me. They were even so unkind as to single out shortstop as a specific need, rather than just say they needed to bolster the infield. I know I had a poor season with the glove last year. I know it better than anyone. But there was that new turf-and-dirt infield at Candlestick Park, for instance. I’m not using that as a primary excuse for a poor year nor using it as a means of getting sympathy. Nearly every shortstop who came into Candlestick last season came to me and asked: “How can you play this infield?”18

Lanier’s display of injured pride got the attention of Giants management, especially team skipper Charlie Fox, who remarked, “It struck me that we had all got down on Hal. We had created a situation where we were all psyching him out. None of us thought he could hit. A lot of us knocked his fielding. So it spread out until it influenced him. It was a negative condition and I’m sure that he became convinced that because we didn’t think he was adequate, he began to think the same way.”19

In May of 1971, the world learned that Lanier had epilepsy — a temporary breakdown of cerebral and physical functions that led to more or less severe seizures. He had suffered three of them since turning pro, and had begun wearing a Medic Alert bracelet so that medical workers would be aware of his problem. But there was social as well as personal value in the revelation. Lanier wanted to send a message to the country’s youth — “some kids with epilepsy might think they shouldn’t go into sports.” At the same time, it also alerted his teammates: “I think all the guys on the team are aware of the situation. They should be, so in case I have another attack they won’t get excited.”20

At first, though, Lanier believed that disclosing his condition would lead to misjudgment about his ability: “Since I’ve never been bothered by epilepsy on the field, or all that much off of it, I didn’t see what good it would serve to talk about it.” It was Medic Alert’s decision to make it public.

His first attack had happened during a road trip to Reno in 1962. “We were in Reno for a game when I took a morning shower and simply passed out, for about two minutes. When I came to I felt a little weak and dizzy but being I was only 19 I didn’t give it another [thought]. It didn’t seem important. You have to remember, too, that my diet probably wasn’t what it should be and if I remember I was up a little late the night before.” A visit to the doctor did not prompt any alarms; the physician ascribed the attack to “high altitude.”

In 1964, a seizure occurred during another morning shower when he was in Florida. At this point, a specialist recognized Lanier’s condition. “It kind of shook me up,” Lanier said. “But the doctor reassured me it would have no effect on me as a ball player. He gave me pills to take, cautioned me against drinking excessively and told me to get a lot of rest.”

There was a third seizure during a road trip to Montreal in 1970 — also during a morning shower. Lanier wasn’t comfortable with all the attention his illness attracted. “I wish, though, that people were interested more in me as a player than one with a handicap, although you can’t blame people,” he said. “I haven’t exactly been setting the world on fire lately.”21

Lanier speculated about a possible factor for the latest seizure: “Last summer, we were playing a lot of afternoon games, and I had skipped my medication a few times. I remember vaguely some jerkiness before the seizure in Montreal, which was my longest, maybe five minutes.” Actually, publicizing his condition inspired others to write to the ballplayer, who felt obliged to listen and, perhaps, offer assistance when he could. “Nobody should be ashamed of it,” said Lanier.22

In early February 1972, the Yankees bought Lanier’s contract and he switched to the American League. “I am still young enough and still capable enough of playing regularly,” said the newly pinstriped infielder. “But I think I am a valuable asset to this club by playing three positions.” . He was correct. Lanier’s ability to play third base, shortstop, and second base provided a raft of options for manager Ralph Houk.23

Although Lanier recognized his worth to the team, he also knew that it wasn’t going to earn him plaudits. “You don’t get in the limelight like the regulars, but you’re valuable because you can play several different positions. They need people like that but there aren’t many of them left,” observed Lanier.24

Houk used Lanier in only 60 games in 1972. Despite Lanier’s understanding of his role, it caused a bit of friction between them. In turn, Houk set the matter straight: “I got you here to be a utility player and whether you like it or not, that’s what you’re going to be. If you don’t like it, if you’re not happy, tell me and I’ll send you someplace else. If you want to stay here, then you’re going to have to stop griping and just do your job when you’re called on.”25

Lanier played in 35 games for the 1973 Yankees; it was his last season in a major league uniform. He served as a player-coach for the Tulsa Oilers of the AAA American Association during the next two years: 103 games and .269 batting average in 1974; 21 games and .203 in 1975.26

In 1976, the St. Petersburg Cardinals in the Florida State League (Class A) were the first team to hire Lanier as a manager. “If they can benefit from what I’ve learned in the major leagues, it’s good for the club,” Lanier explained. “I think I’ve picked up a lot about handling people and managing from the other managers I’ve played under.”27 The team went 70-71. It was the beginning of a managerial career lasting more than 40 years, on and off.

In 1977, Lanier managed the Gastonia Cardinals in the Western Carolinas League (Class D). After Gastonia, it was back to St. Pete. In 1979, the Cardinals sent Lanier to Springfield in the triple-A American Association. Once again, Lanier proved himself — 73-63 record. Once during the season, he suited up as a player for the Redbirds once during the season, going one-for-two. The following year, Lanier guided the Redbirds to the American Association championship.

From 1981-85, Lanier was back in the big leagues, this time as the third base coach for the St. Louis Cardinals. It was a great time for baseball fans in the Gateway to the West — the Cardinals won the World Series in 1982 and the National League championship in 1985, before losing to the Kansas City Royals in seven games in the Series.

Following the 1985 season, Lanier achieved the pinnacle of success as a manager. The Houston Astros chose him to manage the club. The new helmsman envisioned speed as a cornerstone. “I like the club that I’ve seen so far,” he said. “I am a very aggressive manager. I see us doing more running. I like to put people in motion and make the defense come up with a lot of mistakes.”28

Lanier’s assessment meant that the Astros and their aficionados would need to get used to a more explosive offense on the base paths. “I think there are at least five or six people on this team that can steal 25 to 30 bases. This is going to be a more exciting ballgame for the fans,” declared Lanier. For a team following a paradigm of methodical baseball that John McGraw would have embraced, a new dawn emerged over the Astrodome. Lanier explained, “I want to get it in people’s minds to take the extra base. I don’t like to see a club that goes base to base and I think that’s the type of club the Astros have been.” One of Lanier’s first goals was to hire Yogi Berra as a coach.29

Houston’s enlivened style of play paid big dividends. The Astros won the NL’s Western Division by 10 games, and faced the New York Mets in the 1986 NLCS. It was an epic battle, which the Mets Mets won in six games; the Mets won the World Series in seven games against the Boston Red Sox.

The Astros won the first game 1-0 on the strength of Mike Scott’s pitching — 14 strikeouts in a complete game. They lost the next two games; Scott won again in the fourth game, prevailing in a three-hit complete game for the 3-1 victory. The Mets took the next two games and the pennant. Game Six, one of the most thrilling contests in playoff history, lasted 16 innings.

The BBWAA voted Lanier NL Manager of the Year in 1986, an understandable choice. But he was modest in accepting the accolades. “I think I helped bring a winning attitude,” he said. “The ballclub felt it was a good ballclub, but the desire to win this year seemed to be more than it had in the past.”30

In 1987, the Astros stumbled, achieving only a 76-86 record. Lanier looked forward to 1988, saying, “Personnel-wise, I think that we are a better club than we were in 1986. But everything came together that year. We had everybody have good years together, and that’s how you win. That’s why it’s so tough to repeat. It’s just difficult to have everybody come back and have outstanding seasons two years in a row. You might get a few guys to do it, but not everybody.” 31

After the Astros went 82-80 in 1988, Lanier was fired, though he had achieved a record of 22 games over .500 in his three-season tenure. Astros owner John McMullen remarked, “Managing is the hardest job in baseball. It is the culmination of all the possible pressure on an individual. Hal Lanier has been a first-class citizen and done many positive things for the organization. We feel at this time, however, it is best to wipe the slate clean and start over again.”

Lanier responded with grace: “I’ve had three great years with this club but this is not a happy time for anyone. However, I don’t hold any bitterness toward anyone.” Although he remained hopeful and didn’t know it at the time, Lanier had seen the last of the major leagues as a manager. He tried to be philosophical about his state. “I think once you get fired you learn from it, and for the next job it makes you a better manager,” he mused. “I don’t have to look back. Life goes on, and that’s the way you have to look at it.”32

Lanier served as the bench coach for Philadelphia Phillies manager Nick Leyva in 1990. His presence might have raised suspicions if the Phillies stumbled, a possibility that Lee Thomas, the team’s general manager, recognized. “I told Nick when he wanted Lanier, ‘Hal Lanier will help us. He’ll help you.’ But I just don’t want Hal Lanier coming in here if things go bad in the beginning and it’s, ‘Oh boy, here’s Hal Lanier, he’s going to take over. I don’t want that to be the case. And if you can handle that, then fine, have Hal Lanier here.’”33

For a short while, it looked like Lanier might return to the Cardinals. He interviewed to succeed Whitey Herzog as skipper in 1990, but Joe Torre got the job. Lanier lasted one more season in Philadelphia before being dismissed. This began a four-year hiatus from baseball, which ended when he returned to managing in 1996 with the Winnipeg Goldeyes in the Northern League’s North Division (Independent). He stayed with the Goldeyes for 10 years and compiled a 523-360 record, an outstanding .688 win percentage.

In the next few seasons, Lanier managed teams in a number of leagues in Independent baseball. In 2006, he moved to the Northern League’s South Division, managing the Joliet (IL) Jackhammers for two seasons. He ended his Joliet tenure with an 87-106 record. In 2008, Lanier joined the Sussex (NJ) Skyhawks in the Canadian-American Association (Independent), leaving with a 90-98 record after two seasons. In 2010, he went to the Normal (IL) CornBelters in the Frontier League (Independent), where he stayed for two seasons; his record there was 90-102.

For the next three years, 2012-14, Hal Lanier was actually out of baseball, retired. As of this writing (2018), Lanier has been with the Ottawa Champions in the Canadian-American Association, where he’s notched a 139-155 record from 2015 to 2017.

Lanier has married three times. He has two daughters — one from each of the first two marriages and a stepdaughter from the third. He’s been married to his third wife, Pam, for 20 years.

In looking back over his long career — as player, scout, coach, and manager — Lanier has pride and satisfaction in his contributions to baseball:

I think that managing and being on the field is where I’ve always wanted to be. I was very fortunate to coach under Whitey Herzog for five years. I watched how he managed his pitching staff. It’s surprising that I didn’t get back into the majors in a managing capacity. Independent baseball is tough because I have to talk to agents and recruit my own players. It’s about players getting a second opportunity if they didn’t get drafted out of college or they got released from ball clubs. It makes me happy when players I’ve managed get signed in the minor leagues and the major leagues.

One of my favorite memories of growing up is my first meeting with Willie Mays when I was 10 years old. My father was with the Giants when they were at the Polo Grounds. Willie used to take kids to centerfield. I ended up playing eight years with him. At my first Giants Spring Training camp in 1962, Willie had a big welcome banner that said ‘Welcome, Maxie,’ a nickname based on my father’s name. It was a big thrill to play with five Hall of Famers in San Francisco — Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Gaylord Perry, Orlando Cepeda, and Juan Marichal.”34

Last revised: July 6, 2021 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Tom Schott and fact-checked by Steve Glotfelty.

Notes

1 Randy Reinhardt, “Belters’ boss: Lack of basics lead to loss,” Pantagraph (Bloomington, Indiana), July 1, 2010, 10.

2 Richard Goldstein, “Max Lanier, 91, Who Challenged Baseball’s Reserve Clause, Is Dead,” New York Times, February 9, 2007, A17. “The Mexican League, run by brothers Jorge and Bernardo Pasquel and operating apart from the major league-minor league structure, was offering high salaries to lure players. Lanier, who was earning $10,500 with the Cardinals, agreed to a five-year Mexican League deal paying him $20,000 a year plus a bonus.” David George Surdam, The Big Leagues Go to Washington: Congress and Sports Antitrust, 1951-1989 (Urbana, Chicago, and Springfield: University of Illionis Press, 2015) 15.

3 Art Rosenbaum, “How’s Hal Doing?,” Tampa Bay Times, August 30, 1964, 90.

4 Harold Clifton Lanier file, National Baseball Hall of Fame (HOF), Cooperstown, NY; Larry Bugg, “Astros’ Lanier always enjoys coming to his Florida hideaway,” Tampa Tribune, January 1, 1988, 46.

5 Curley Grieve, “Giants Pay $90,000 For Son of Lanier,” San Francisco Examiner, June 17, 1961, 37; Lanier file, HOF; Tom Kelly, “Giants Call Up Hal Lanier To Help Slumping Infield,” Tampa Bay Times, June 19, 1964, 37.

6 John Bowman, “Manager of Astros has a home base on Suncoast,” Tampa Bay Times, April 6, 1986, 96.

7 “Hot Tamale Javier Cools Giants: Hal Lanier, Son of Max, Makes Debut,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 19, 1964, 30; Jack Hanley, “Press Box Views: Rookie Hal Lanier Right At Home; His Bat Gave Giants A Big Lift,” [San Rafael, CA Daily Independent Journal, June 23, 1964, 13; Bob Stevens, “The Best Since Whitehead? Giants Raving Over Lanier,” Sporting News, July 4, 1964, 7.

8 Kelly, “Giants Call Up Hal Lanier To Help Slumping Infield;” Emmons Byrne, “Lanier Leads Giants Past Cards, 7-3,” Oakland Tribune, June 22, 1964, 34.

9 Byrne, “Lanier Leads Giants.”

10 “Hal Lanier Earned His Job With Giants,” [Jackson, MS] Clarion-Ledger, March 22, 1965, 13; Jack McDonald, “Soph Lanier Already Ticketed As Giant Take-Charge Infielder,” Sporting News, March 27, 1965, 29.

11 Bob Stevens, “Giants Junk Power Tactics for Accent On Speed, Defense,” ibid., April 24.

12 George C. Langford, “Hal Lanier’s Sprint A Pleasant Surprise,” Town Talk, September 20, 1965, 9.

13 Bob Stevens, “Lanier Rugged Ringleader Of Top-Notch Giant Infield,” Sporting News, March 19, 1966, 13.

14 Ibid.

15“Hal Lanier Faces Military Service,” Corpus Christi Caller-Times, March 1, 1967, 33; Bob Stevens, “A Critical Year Coming Up for Giants’ Lanier,” Sporting News, February 11, 1967, 21; Harry Jupiter, “Switch Hitting Aids Lanier,” San Francisco Examiner, March 2, 1967, 43.

16 Bob Stevens, “Hunt, Lanier Seal Hole, Make Giants’ Defense Leakproof,” Sporting News, June 15, 1968, 12.

17 Wells Twombly, “Wells Twombly,” San Francisco Examiner, May 30, 1970, clipping in HOF, Cooperstown, NY.

18 Pat Frizzell, “Giants’ Search for Shortstop Aroused Lanier’s Resentment,” Sporting News, December 19, 1970, 41.

19 Wells Twombly, “Lanier Reprieve May Pay Dividends,” San Francisco Examiner, March 10, 1971, 53.

20 “Giants’ Hal Lanier Joins Medic Alert,” [San Mateo, CA] Times, May 13, 1971, 30; “Says Hal Lanier: Epilepsy No Handicap,” Tampa Tribune, May 13, 1971, 69.

21 Previous paragraphs based on “Hal Lanier Reveals Epilepsy Condition,” Bridgeport CN] Post, May 16, 1971, 81.

22 Murray Olderman, “Hal Lanier Isn’t Ashamed Of Epilepsy,” [Uniontown, PA] Evening Standard, August 17, 1971, 12.

23 “Yanks Acquire Hal Lanier From Giants,” [Pottstown, PA] Mercury, February 3, 1972, 31; Jim Selman, “Utility Man Lanier Valuable To Yanks,” Tampa Tribune, March 21, 1973, 63.

24 John Bowman, “Hal Lanier No Star, But Sees Security As Utility Infielder,” Tampa Bay Times, October 20, 1973, 65.

25 Phil Pepe, “Lanier on Houk’s Wave-Length Now,” New York Daily News, March 24, 1973, HOF, Cooperstown, NY.

26 Ron Martz, “Lanier tries different route back to big-time,” Tampa Bay Times, April 5, 1975, 35.

27 Bob LeNoir, “After 15 years, Lanier back home,” ibid., April 13, 1976, 11.

28 “Astros name Lanier manager,” Asbury Park NJ Press, November 6, 1985, 94.

29 “New Astro boss flashes steal sign,” Press Democrat, November 6, 1985, 37; “Lanier named Astros’ pilot, wants Berra as coach,” New York Post, November 6, 1985, 62.

30 “Astros’ Lanier basks in glow of honor,” Battle Creek (MI) Enquirer, November 6, 1986, 23.

31 Peter Pascarelli, “N.L. Beat: Lanier Is Quietly Confident About Astros,” Sporting News, April 11, 1988, 29.

32 Marc Topkin, “Lanier waits and prepares for another chance,” Tampa Bay Times, August 13, 1989, 44.

33 Frank Dolson, “No shortage of replacements for the Phils’ Leyva,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 18, 1990, 54. The Phillies fired Leyva at the beginning of the 1991season after the team started with a 4-9 record.

34 Telephone interview, Hal Lanier w/author, March 20, 2018.

Full Name

Harold Clifton Lanier

Born

July 4, 1942 at Denton, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.