J. C. Martin

He delivered big hits on occasion but is still asked most often about a thrown ball that struck him in the wrist while he was running to first base in the 1969 World Series.

“I kid around with the fans and show them how I swelled up. I just stick my arms out. I don’t care what some people say about the play or what I did. The umpire said I was safe so I must have been safe. They show my old play again at first base and I could see that ball bouncing off my wrist. It didn’t hurt a bit then and it doesn’t hurt now. I just get a kick out of seeing that ball roll away and old Rodney [Gaspar] running around those bases; and getting in for that winning run. That’s a satisfying scene, yes sir, it certainly is.”1

J.C. Martin smiled when he considered the turn of events that made him a participant in the Series rather than a spectator.

Joseph Clifton Martin was born on December 13, 1936, in Axton, Virginia. The town is eight miles north of the North Carolina state line. Both of his grandparents were named Joseph. To avoid confusion (along with the Southern tradition of referring to people by using initials), the family called him by his initials, J.C.

In his youth, Martin was an active outdoorsman. J.C. and his younger brother, Melvin, hunted coon and possum and fished in a river along the family farm. They would take their catch to their grandpa’s house. In return, Grandpa would fatten the kids up with their catch along with cornbread and buttermilk.

Martin wanted to be a big-league ballplayer. His parents suggested that to fulfill this dream, he could not drink or smoke. His father was deputy sheriff of the county. After school, J.C. would stop off at the county jail to visit his father. As he saw the inmates, he witnessed first-hand how not to live.

Martin told an interviewer he didn’t know where he would be if he were not raised a Christian. His hero was second baseman Bobby Richardson of the New York Yankees. Bobby and his roommate, Tony Kubek, were dubbed the Milkshake Twins for their decorous lifestyle.

At Ridgeway High School, Martin lettered in baseball, football, and basketball, and ran track. Several colleges offered him scholarships. Eight baseball clubs extended offers. In addition, he met a young woman named Barbara Cox.

Harry Postove, a scout for the Chicago White Sox, had watched Martin since his sophomore year. Postove assured Martin he would advance rapidly through the Chicago minor-league system as a first baseman. Martin signed with the White Sox for a $4,000 bonus and reported to the Holdrege White Sox of the Nebraska State League.

In 1956, the Nebraska State League was a Class-D rookie league. Rosters combined local baseball stars with collegiate and high school players. The schedule started on July 1 and concluded on Labor Day so players could return to their studies. The Holdrege White Sox played at Holdrege Fairgrounds Park, a decrepit ballpark without a grass infield. Sand and gravel combined with dirt to create a hazard for the players. The grandstand was unkempt. During the winter, glass windows were broken by vandals.

For the 19-year-old Martin, playing in Holdrege was an awakening. He discovered that many ballplayers were not pure as he envisioned them in his youth. After games, he isolated himself from teammates who attended parties to drink, smoke, and meet women. In addition, the pay was low, travel was by bus, and the ballpark lighting was poor.

Playing first base, Martin hit .276 in 64 games, scored 64 runs and had a .481 slugging average. Teammates and opponents who wound up in the majors included Alan Brice, Jimmy Hall, Camilo Carreon, Gary Peters, Deron Johnson, Jim Perry, Bob Allen, and Hal Reniff. After the season, Martin persuaded Barbara to leave college and get married.

In 1957, Martin was promoted to play in the Class-B Three-I League. Martin played only 19 games for the Davenport DavSox, and his lack of experience produced a .208 batting average. Sent down to the Dubuque Packers in the Class-D Midwest League, he hit a respectable .286 with 14 home runs and 64 RBIs. The next season, Martin was summoned to the Duluth-Superior White Sox of the Class C Northern League. In mid-July, Martin led the league with a.358 batting average, on the strength of an 18-game hitting streak. He finished the season batting .330, with 10 home runs and an impressive 86 RBIs.

Martin was promoted to the Triple-A Indianapolis Indians of the American Association for 1959. He hit a steady .287 with 13 home runs and 57 RBIs. His manager was former major leaguer Walker Cooper. Martin earned a September call-up to the White Sox. This was a perfect time to watch how baseball fundamentals were played. The White Sox relied upon solid pitching, good defense, and aggressiveness on the base paths.

The “Go-Go Sox” were managed by Al Lopez. “He was great. Al was the kind of manager who let you play. He wouldn’t run you down by playing you day after day after day. He knew the game. He got me into the big leagues and I have nothing but respect for him. We all did,” said Martin.2

Martin recalled his initial call-up to the big leagues. “It was pretty exciting. I think six guys came up from Indianapolis. I came up along with Johnny Callison, Joe Hicks, and Ron Jackson. I’m sure there were a few others.”3 The 22-year-old made his debut at Comiskey Park on September 10 against the Washington Senators. Camilo Pascual struck him out in his first major-league at bat.

Martin recalled the game when the Sox clinched the pennant in Cleveland “Talk about exciting. . . . It was a real thrill. I still remember Jerry Staley coming in to pitch to Vic Power. Staley threw one pitch, Power hit into a double play and that was it. It was pandemonium in the locker room. Then we flew right back to Chicago, to Midway Airport. I don’t know how many people were there but it was a lot (The Chicago Sun Times estimated the crowd at 125,000). I know we had to get on a bus and drive out to where our cars were parked.”4

Martin recorded his first major-league hit and RBI on the final day of the season in Detroit. It was a single to center field off lefty Pete Burnside. He finished the season with one hit in four at-bats, playing two games at third base. Being a late season call-up, Martin was ineligible for the World Series, which the White Sox lost to the Los Angeles Dodgers in six games.

The next season, Martin played Triple-A ball with the San Diego Padres. His manager, George Metkovich, believed Martin would make it to the majors. He batted .285 with 13 home runs and 73 RBIs, and was recalled to the Pale Hose that fall.

The spring of 1961 was difficult for Martin. At Sarasota, Florida, his fielding was atrocious. His hitting was equally poor. Before an exhibition game, he hurt his back in a game of pepper. Manager Lopez ordered him out of uniform for several days to rest. Known for patience with rookies, Lopez was unruffled by Martin’s errors. The skipper believed his glove was the culprit. Baseballs would skid off his fingers. Lopez assigned future Hall of Fame shortstop Luis Aparicio to work with Martin. He let Martin borrow his glove. There was an immediate difference, and the Sox ordered the Aparicio model glove for Martin. During the season, his fielding recovered but he hit only .230, with 5 home runs and 32 RBIs. The White Sox slipped to fourth place. As a consolation prize, Martin was named to the Topps Chewing Gum rookie team chosen by young card collectors.

After the 1961 season, during the White Sox organizational meetings, Martin’s name was discussed as a possibility for the catching position. Offensively, he lacked power required for a corner infielder. General manager Ed Short sought a third-string left-handed-hitting catcher and suggested converting Martin to a catcher. Lopez agreed. “(In 1962) I went down to Savannah, Georgia (in the South Atlantic League), for three months to see if I could learn the position,” Martin said.5 His manager there was former White Sox catcher Les Moss, and Moss taught Martin how to catch. Martin had a strong fielding percentage .986, but set a league record with 32 passed balls. However, he progressed as a batter, hitting .328 with 8 home runs and 52 RBIs.

After the season, Martin returned to the White Sox as a reserve catcher. On September 10 at Comiskey Park, Martin started his first major-league game as a catcher, calling signals for Ray Herbert. Martin was excellent as Herbert pitched a complete game 4-3 victory over the Kansas City. Martin singled off Bill Fischer in the sixth.

Eddie Fisher, Hoyt Wilhelm, and Wilbur Wood were Chicago knuckleball pitchers in that era. The challenge for Martin was to handle the baffling serves. “It was exciting because you never knew where the ball was going. . . . It could do a 90-degree break and then double back! If you didn’t wait, you just couldn’t see it. You’d have to snatch it when it was right on top of you. It’s the best pitch I’ve ever seen a relief guy throw.” Each threw it differently. “Hoyt had the most consistent pitch. The other guys had good ones but every so often they’d throw one that would spin and then they’d get hit. Hoyt’s always worked,” recalled Martin.6 According to Charlie Metro, a White Sox coach under Lopez, the manager would bring in Wilhelm and Martin into the game as a team. “He was the only guy who could catch Hoyt’s knuckleball,” Metro said.7

Martin learned the catching position sufficiently to be inserted as the Sox’ Opening Day catcher in 1963, at Tiger Stadium. The Sox won and manager Lopez, impressed with Martin behind the plate, made him the first-string catcher. However, Martin hit a miserable .205 that season. In 1964, catching in 120 games, Martin fell below the Mendoza line at .197 as the White Sox finished second, one game behind the Yankees. The Sox won their last nine games, but the Bronx Bombers won enough to hang on. Martin said the Yankees of that era “just had so much that nobody could compete. … Their benchwarmers could be regulars on other teams.”

In 1965, while handling knuckleballs from Fisher and Wilhelm, Martin set a post-1900 record (subsequently broken by Geno Petralli) with 33 passed balls. However, Martin rebounded for his most productive season as a hitter. His batting average rose to .261 in 119 games.

That November, Lopez resigned as White Sox manager. He was replaced by Eddie Stanky, the combative baseball lifer known as “The Brat.” In retrospect, Martin was unimpressed by his new skipper “He was tough. He was so different from Al. He intimidated. He’d fine guys for anything. He knew baseball … no question, but he couldn’t manage people. After a little while the players would lose interest and loyalty. He actually pumped up the other team more because he was always getting on them. I’ll never forget it was in 1967 we got into Boston and went to bed. The next morning I pick up a Boston paper and see this big headline. ‘Yaz an All Star from the neck down.’ Stanky ripped him to the press. Man, Yaz wound up hitting everything we threw at him but the rosin bag!”8 Martin had had a decent season at the plate in 1966 with a .255 batting average. However, he lost his starting job to John Romano. After the season, Romano was shipped to St. Louis. Martin caught 96 games and hit .234 in the epic 1967 season, in which four teams scrapped for the pennant, eventually won by Boston.

That 1967 White Sox club was known as the latter-day Hitless Wonders because no regular batted over .250. At one point in mid-August, Martin was leading the team in batting. How did the club stay in contention? “We had pitching (league-leading ERA of 2.45) and defense. If you have that, you’ll be in every game and we knew how to manufacture runs. Guys knew how to bunt, hit and run, steal bases. We knew what we had to do to win.”9

On September 10, Martin was behind the plate as Joe Horlen pitched a 6-0 no-hitter over Detroit in the first game of a doubleheader at Comiskey Park. It was the first White Sox no-hitter since Bob Keegan no-hit the Senators in 1957.

“Joe was great that day,” Martin recalled. “In the ninth inning we got the first two guys out. I called time and went out to the mound. I asked Joe what he wanted to throw to the next hitter, Dick McAuliffe. Joe paid me a great compliment because he said, ‘You’ve called the first 8⅔ innings, you finish it up.’ I knew that McAuliffe was both a good pull hitter and a good inside-out opposite-field hitter. I wanted to take something away from him, so I decided we were going to pitch him away. Dick hit one to our shortstop Ron Hansen, who threw him out. . . .” 10

On November 27, 1967, the New York Mets acquired Martin to complete a deal made during the season. A few weeks later, the Sox sent Al Weis and Tommy Agee to the Mets in another trade. The three players were reunited and played key roles in the Mets’ 1969 World Series victory.

In 1968, manager Gil Hodges slated Martin to share the catching chores with Jerry Grote. On Opening Day, Martin caught Tom Seaver at San Francisco. The Giants won the game with three runs in the bottom of the ninth inning; in that inning, Martin’s finger was broken when it was struck by a foul ball off the bat of Jim Ray Hart. Martin was placed on the disabled list. He wound up playing only 78 games for the year, hitting .225 with three home runs.

The Mets’ catching combination of Grote and Martin had a total of 15 years of big-league experience entering the 1969 season. This was imperative for a pitching staff whose first four starters (Seaver, Jerry Koosman, Jim McAndrew, and Gary Gentry) had only three full seasons among them.

Grote got the bulk of the starts behind the plate that year, but as the dog days of summer ended, manager Hodges skillfully played Martin against right-handed pitchers to provide Grote rest. Increased action down the stretch drive enabled Martin to contribute in the postseason. In Game Three of the National League Championship Series, in Atlanta, in the top of the eighth inning, New York loaded the bases with two outs. Martin pinch-hit for Seaver and lined a clean single to clear the bases and provide the Mets with a four-run lead.

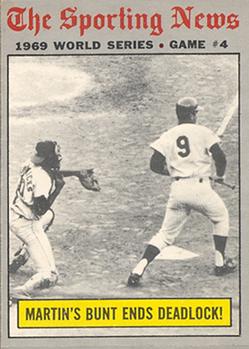

In the World Series, there were many heroes for the upstart Mets. Martin, even though he appeared in only one game and had no official at-bats, may have been the unlikeliest. In the bottom of the 10th inning of the fourth game, with the Mets leading the Series two games to one, Martin pinch hit for Tom Seaver with runners at first and second and nobody out in a 1-1 game.

In the World Series, there were many heroes for the upstart Mets. Martin, even though he appeared in only one game and had no official at-bats, may have been the unlikeliest. In the bottom of the 10th inning of the fourth game, with the Mets leading the Series two games to one, Martin pinch hit for Tom Seaver with runners at first and second and nobody out in a 1-1 game.

As Orioles pitcher Pete Richert wound up, Martin squared to bunt and laid down a beauty. Richert grabbed the ball and threw to first. The throw appeared to have Martin beat. However, it struck Martin on the left wrist and bounded across the infield dirt between first and second base as pinch-runner Rod Gaspar scored the game-winning run from second base and the Mets swarmed around Martin. The umpires ruled that Martin had not attempted to interfere with the ball.

The next morning, controversy swirled around the play. Press box observers clearly believed Martin was out of the baseline, in fair territory, when the throw hit him, and under the baseball rules should have been out. Later photos indicated conclusively that that was the case. Years later, Martin said he believed getting hit with the throw was “just a coincidence,” but he acknowledged that he had done what he could to allow circumstance its best opportunity.

“You try to do everything you possibly can,” he said. “You know from experience that if you run close to the first-base line, the throwing angle is very narrow, particularly if the pitcher is left-handed (as Pete Richert was) and has to turn to make the throw. So you run as close as you can. I wasn’t thinking about getting hit or anything. I was just looking to shield the ball from the man covering first. As it turned out, the ball happened to hit me on the left wrist. But there was no argument at the time. All the controversy was in the media the next day.”11

Even Seaver admitted years later that the films showed Martin ran out of the baselines. But it was too late. If Martin had been called out for interference, Gaspar would not have scored on the play, leading the way for the Mets to win the Series the next day.

Before the 1970 season, Martin returned to the Windy City, this time on the North Side. The Chicago Cubs acquired him for rookie catcher Randy Bobb. Playing behind workhouse Randy Hundley, he caught only 36 games and had but 12 hits all season, for a .156 batting average.

In the winter of 1971, Cubs pitching coach Verlon Walker was hospitalized for a persistent fever. General manager John Holland named Martin the interim pitching coach. When the season began, Mel Wright, a coach in the Cubs organization, replaced Martin. For the 1971 season Martin boosted his offensive production (.264, with 2 home runs and 17 RBIs), and was excellent defensively.

Martin played his final season in 1972. At the age of 35, he batted mostly against right-handers; defensively, his throwing arm had diminished and he committed an abundance of errors. He caught in only 17 games and batted .240 in 50 at-bats. Martin was released before the ’73 season. He spent the 1974 campaign as the bullpen coach on the staff of manager Whitey Lockman, who was fired in midseason.

In 1975 Martin worked alongside the legendary Harry Caray on WSNS-TV for the White Sox. It was an unhappy experience. “I didn’t really fit in with Harry,” Martin recalled. “He didn’t want to work with me. We didn’t hit it off at all. I wasn’t used to working with a guy that had that kind of authority and Harry used that against me. I was only there for one year. . . . Harry just left me out to dry. I’ll give you an example. We were in Milwaukee doing a game and the Brewers had a pregame activity which saw the Milwaukee wives playing a game before the regularly scheduled one. That game caused the regular game to start late. Harry opened the telecast and then just left the booth. He left me there by myself for it must have been 15 to 20 minutes.”12

Martin was far from a superstar (a career .222 hitter), but he cherished his time in the major leagues. “I wouldn’t trade it for anything,” he said. “I spent 14 years in the big leagues seeing the best players ever, guys like Bob Gibson, Willie Mays, Carl Yastrzemski. Players like that just aren’t around anymore. Baseball was better back then. … they didn’t have the DH, which has killed all the suspense in the American League, and the ballparks were fair. You didn’t have this emphasis on hitting home runs all the time. It was great.” Martin caught five Hall-of-Fame pitchers: Wynn, Wilhelm, Seaver, Nolan Ryan, and Ferguson Jenkins.

Martin was one of the Amazins’ good luck charms. He fulfilled his dreams. While he played in the majors, he traveled first class, and ate in the best restaurants. Yet he never ate a heartier meal than those his Grandpa cooked for him back in his youth in Virginia.

Last revised: November 1, 2018

This article originally appeared in SABR’s “Go-Go To Glory: The 1959 Chicago White Sox“ (ACTA, 2009), edited by Don Zminda. It also appeared in SABR’s “The Miracle Has Landed: The 1969 New York Mets“ (Maple Street Press, 2009), edited by Matt Silverman.

Notes

1 Maury Allen, After the Miracle: The 1969 Mets Twenty Years Later (New York: Franklin Watt, 1989), 122-123.

2 http://www.whitesoxinteractive.com; WSI (White Sox Interactive News); Flashing back with J.C. Martin with Mark Liptak.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Charlie Metro with Tom Altherr, Safe by a Mile (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2002), .278.

8 Liptak-Martin.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Stanley Cohen, A Magic Summer — The ’69 Mets (New York: Harcourt Brace Jonavich Publishers, 1988), 292-293.

12 Liptak-Martin.

Full Name

Joseph Clifton Martin

Born

December 13, 1936 at Axton, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.