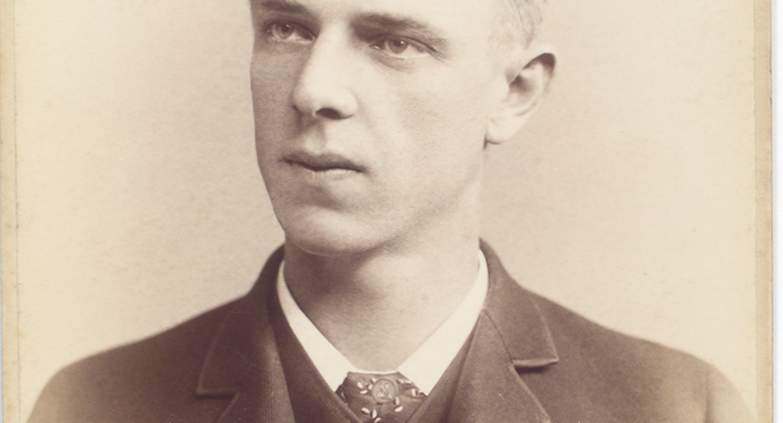

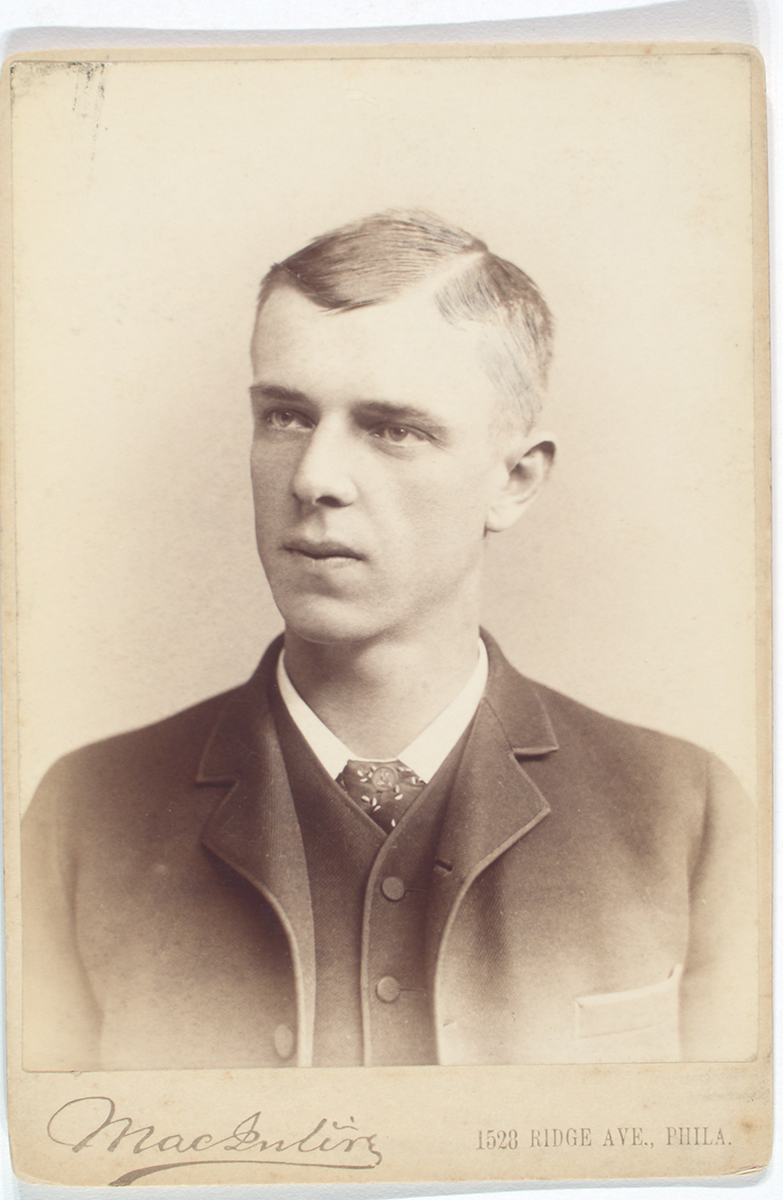

Charlie Ganzel

“We are a baseball family, I guess,” said Charlie Ganzel of his clan in a 1904 interview.1 One of a bevy of family members who achieved success in baseball, Charlie was arguably the most prominent of the Ganzel brothers. Although he was a key contributor to five pennant-winning National League teams during the late nineteenth century, the part-time player seemed forever destined to play in the shadows of teammates who were among the biggest stars in the game. Nonetheless, media and peers recognized Ganzel throughout his career as being one of the finest catchers and most versatile players in the game.

“We are a baseball family, I guess,” said Charlie Ganzel of his clan in a 1904 interview.1 One of a bevy of family members who achieved success in baseball, Charlie was arguably the most prominent of the Ganzel brothers. Although he was a key contributor to five pennant-winning National League teams during the late nineteenth century, the part-time player seemed forever destined to play in the shadows of teammates who were among the biggest stars in the game. Nonetheless, media and peers recognized Ganzel throughout his career as being one of the finest catchers and most versatile players in the game.

Charles William Ganzel was born in Waterford, Wisconsin, near Racine, on June 18, 1862, to Charles Ganzel Sr. and Elizabeth Ganzel. His father worked as a carpenter and his mother was a homemaker. Both of Ganzel’s parents emigrated in the mid-nineteenth century from Prussia (Germany) to the United States, where they started their family, which ultimately grew to include 10 children. Charles – whose nickname is often also spelled “Charley” – was the third oldest of the children, who included five sisters (Anna, Ida, Julia, Lizzie, and Minnie) and four brothers (Frederick, George, John, and Joseph). The Ganzels called the Racine area home until around 1883, when they relocated to Minnesota. After spending four years in the Twin Cities, Charles Sr. and Elizabeth again relocated the family – this time permanently – to Kalamazoo, Michigan. And with all but one of the Ganzel boys eventually spending notable time playing professional ball in Michigan, it is perhaps not surprising that the clan was known as the “first family of Michigan baseball.”2

Ganzel’s parents preached to their children the virtues of avoiding alcohol, and attributed to their espousal of clean living the family’s overall good health and athletic giftedness – particularly as it related to their sons. “The children of the elder Ganzels, especially the boys, are giants in size, all but one measuring over six feet one inch and weighing close to 200 pounds each,” noted the Detroit Free Press before also highlighting that the boys were “naturally of an athletic turn.”3 Indeed they were athletic, as Ganzel and his four brothers all found success in baseball at various levels. Frederick, his older brother, had the promise of a professional career dashed by an ankle injury after playing years of independent ball, while younger brothers George and Joseph each made it to the minor-league level.4 And John, the youngest and most successful of Ganzel’s baseball-playing brothers, played for five big-league teams between 1898 and 1908 before spending two seasons as a manager in the National and Federal Leagues. “It is to the fact that they have never used liquor that the sons attribute their success on the diamond,” wrote the Detroit Free Press, echoing the sentiments of the family’s patriarch and matriarch.5 In actuality, the success the sons achieved was perhaps driven more by genetics, as their father himself was reputedly at one time a noted player.6

Ganzel spent his formative years residing in a “little house” on the south side of Racine, where he “played ball on the prairies south of the city and on the [Racine College] grounds.”7 In 1880 the Third Ward baseball team was organized in Racine. Although comprising solely local players, the amateur club was “probably was one of the outstanding baseball outfits representing the city.”8 Ganzel, at the time in his late teens, honed his craft for the talented Third Ward club, along with his brother George. When not playing ball, he was employed as a painter, according to census information. Additionally, an 1887 news story reported that he also had spent time working in a blacksmith shop earning $1 a day.9 In a show of respect for the native son, Ganzel was posthumously inducted into the Racine Athletic Hall of Fame in 1969.10

A 1914 newspaper article in Ganzel’s file at the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum indicates that his first foray into professional baseball came in 1882 with Grand Rapids of the Northwestern League. This is dubious, however, as that league did not begin play until 1883. More likely is that there was confusion with his brother John, who played for the Grand Rapids Bob-o-Links of the Western League at the beginning of his professional career. What is for certain is that upon his family relocating to Minnesota in 1883, Ganzel played for the semipro Minneapolis Brown Stockings. Although he later recalled that he manned first base for the team, newspaper box scores of the day indicate that Ganzel displayed early signs of the versatility that later became one of his hallmarks, as he frequently also bounced around to various infield and outfield positions.11 And in a late-July game, he did some “pretty work” behind the plate, which was certainly a harbinger of things to come.12 Comprehensive 1883 season statistics are not available for the right-handed batter and thrower; however, Ganzel was “considered one of the most certain players in the club.”13

With the independent Minneapolis club seeking to join the fully professional Northwestern League for the following campaign, team ownership and management sought to stack their roster with “real ball players” in lieu of simply harvesting local talent.14 This forced several of the old Brown Stockings to find new teams – including Ganzel. Latching on with the neighboring St. Paul club, the 21-year-old got his first taste of professional ball in 1884 competing in the Northwestern League. Ganzel began the season primarily playing first base for St. Paul, but also exhibited some solid play behind the plate in an early-season contest against Stillwater. “He has the stuff in him for a fine catcher,” the St. Paul Globe presciently opined after this performance.15 Despite finishing the season hitting .189 and being criticized by the press for his lack of speed, the burgeoning backstop was still regarded as being one of the best players on the team.16

In an interview two decades later, Ganzel reflected on his shift in positions during the season. “In 1884 I was with St. Paul as a first baseman, and in the middle of the season I started in to catch,” he recalled. “This was mainly due to Elmer Foster, the pitcher. They had no one to catch him, and I broke in with him, and after that catching was my home position.”17 Ganzel employed an interesting technique to improve upon the inferior protective catching gear of the day. “In those days the insufficient protection of the gloves caused the hands to swell to double their usual size,” he remembered. “I used to get a piece of beefsteak and put it inside of the glove. This served to moisten my hands and served also as a protection.”18

Upon the conclusion of Ganzel’s first professional season in baseball, another one immediately began. In September, the St. Paul club joined the Union Association – a fledgling (and ultimately doomed) major league – at the tail end of that league’s 1884 campaign. Although the team played just nine games to wrap up the season, Ganzel’s appearance in seven of those contests constituted his first big-league experience. “That year’s playing was the hardest of my career,” he later admitted.19 And with the future of his St. Paul club being in doubt, Ganzel quickly sought opportunities to take his talents elsewhere.

In the fall of 1884, it was frequently reported that he had agreed to play for Kansas City in 1885.20 Although it is possible Ganzel signed with Kansas City’s Union Association club shortly before it (and the league) disbanded, more likely is that the reports were incorrect or speculative.21 What is for certain is that Ganzel accepted an offer (that he recalled as $1,500) to join the Philadelphia Quakers of the National League for the 1885 campaign.22 The 6-foot, 180-pound catcher’s time in Philadelphia was disappointing, however. Appearing in less than one-third of the team’s games in 1885, Ganzel featured a .168/.194/.208 slash line, and was relegated to being the club’s third-string catcher behind Andy Cusick and Jack Clements. After rumors swirled of his involvement in a possible transaction with Washington during the offseason, he found himself back with Philadelphia for the 1886 season.23 Things went from bad to worse, however. “In the spring of ’86 I refused to report, owing to a cut of $100 in salary, for then there was no clause in the contract relating to cutting,” Ganzel later recalled. “I was then living in Minneapolis and I received a letter from the club stating that unless I did report, my name would be blacklisted.”24 Under this coercion, he relented and reported to the Quakers – although he requested his release.25 The admittedly dissatisfied catcher went hitless and played poorly behind the plate in one game before being granted his release.26 Poor play aside, the team reportedly cut ties with him primarily because “the club had more catchers than it needed.”27 Corroborating this report, Philadelphia manager Harry Wright reportedly commented that Ganzel would be an asset to any team if given regular playing time.28 Despite his difficulties in Philadelphia, Ganzel still considered Wright the finest man he had ever met.29

Although clubs in the American Association had rumored interest in securing his services, Ganzel remained in the NL upon signing with the Detroit Wolverines as a backup to star catcher Charlie Bennett in June 1886.30 “Philadelphia has earned Detroit’s sincere thanks. In Ganzel we have received a first-class catcher,” the Detroit editor of Sporting Life asserted. “He is a jewel and will prove a splendid substitute for Charley Bennett.”31 Ganzel did not disappoint, making an impact with the club in his first appearance. “Ganzel had sat on the players’ bench for two days and his appearance created a favorable impression. But few expected he would acquit himself in the superior manner in which he did,” reported the Detroit Free Press. “He caught admirably and showed that he could throw by cutting off two attempts to steal second. His style is artistic, and the Detroit Club has in him a valuable addition to the nine.”32 Philadelphia media also took note of the immediate success of their local club’s former backstop. “Ganzel did himself proud on Tuesday, his record for the afternoon being six put-outs, three assists, no error and one of the ten hits made by the home team,” the Times (Philadelphia) reported. “Everybody here [Detroit] was happy over the new acquisition and the prophets, especially those who are without honor, went about predicting that Detroit’s ‘G.G.’ battery (Pretzels] Getzien and Ganzel), would soon do as good work as the ‘B.B.’ pair – Lady] Baldwin and Bennett.”33 (The so-called prophets proved to be correct, as the future success of the “G.G.” battery led the duo to become more famously dubbed the “Pretzel Battery” – owing to their German heritage.)34 Building on his strong start with Detroit, Ganzel continued his fine play as a very capable backup to relieve the veteran Bennett. All told for Detroit in 1886, he played in 57 games, and hit a solid .272 with one home run and 31 RBIs to contribute to the Wolverines’ second-place finish in the NL.

Although Detroit again slated Ganzel for a substitute backstop position as they headed into the 1887 season, the club gave him the opportunity to take on a much more prominent role with the veteran Bennett battling injuries.35 Appearing as a catcher in 51 games – the most catching appearances on the club – Ganzel acquitted himself quite nicely. Despite featuring offensive statistics that were not overly impressive – he hit .260 with no home runs and 20 RBIs – his play behind the plate was widely lauded. In addition to calling Ganzel a “phenomenal catcher,” the Boston Globe had this to say about the 25-year-old: “He has great reach, very large hands, and is an excellent back stop. No pitcher is too speedy for him and his long reach enables him to save a good many wild pitches.”36 The New York Clipper also offered a glowing review of Ganzel’s second season with Detroit: “Last season [1887] he caught in nearly one half of the championship games his club played, and to his efforts, as much as any other man, is due the high standing the team was able to take in 1887.”37 By season’s end, Ganzel was widely recognized as a key cog that helped lead the Wolverines to the NL pennant and a pre-modern World’s Series championship over the American Association’s St. Louis Browns. At the dignitary-filled banquet celebrating the champion Wolverines on October 24, team owner Frederick Stearns summed up Ganzel’s significant contributions thusly: “The man who is the backbone of the nine, Bennett, could not join us till August, and nothing but his able ally and colleague, Ganzel, could save us.”38 For his efforts, Ganzel received a “handsome” gold watch and chain.39 “I think that the Detroit champion team of 1887 was the best team ever got together,” Ganzel opined in a 1904 interview.40

With Bennett returning to health – and lead catching duties – following an injury-plagued 1887 season, Ganzel nonetheless continued to add value to the Wolverines in the 1888 campaign by displaying versatility on the diamond. During the course of his 95 appearances, he played in the outfield and all four infield positions – in addition to providing his usual solid play as Bennett’s backup. Labeled “one of the best all-round players in the country” by Sporting Life, Ganzel finished the season hitting .249 with one home run and 46 RBIs.41 The New York Clipper praised his versatility: “This season [1888] Ganzel has proved himself a valuable all round player. Besides his excellent work behind the bat he has been filling the position of second baseman, during Hardie Richardson’s absence, in a very creditable manner.”42 While Ganzel evolved into a super-sub, the Wolverines devolved into mediocrity due to injuries and team dissension. Resultant poor fan attendance coupled with a roster full of high-payroll stars caused fatal financial problems for the club.43 Amazingly, Detroit ultimately went from being champions in 1887 to defunct after the 1888 season.

As Detroit prepared for its resignation from the NL shortly after the end of the 1888 season, a frenzy of sorts began as other teams attempted to procure many of its stars – with Philadelphia reportedly even offering to purchase the entire lot of Wolverine players.44 The NL’s Boston Beaneaters became the sweepstakes winner once the dust settled in October, however. For the sum of $30,000, Beaneaters director James B. Billings secured the services of five of Detroit’s prized players: Ganzel, his backstop colleague Bennett, and three of the so-called “Big Four” – Dan Brouthers, Hardy Richardson, and Deacon White.45 Were it not for the other member of the Big Four, Jack Rowe, being quickly dealt by Detroit to the Pittsburgh Alleghenys, Ganzel likely would have found himself moved elsewhere. Boston originally targeted Rowe in the deal; however, upon his lack of availability the club opted for Ganzel in his stead.46 The magnitude of Boston’s transaction – at the time called “the greatest deal in the history of baseball” by one publication – sent shockwaves through the game.47 Similarly, the Boston Herald immediately proclaimed it to be “the greatest deal ever perfected in the history of the national game,” under an optimistically titled headline: “Bostons Are the Champions: That Is, It Is Safe to Bet on It for the Season of 1889.”48 Although White eventually landed in Pittsburgh when his deal with the Beaneaters fell through, Boston was able to execute contracts with Ganzel (at a salary reported in the range of $2,500 to $3,500), Bennett, Brouthers, and Richardson for the 1889 season.49 Reaction to the acquisition of Ganzel was favorable. “Ganzel is also considered one of the best catchers in the league,” wrote the Boston Herald. “He is a remarkably fine thrower and he can stand any amount of punishment at the hands of pitchers.”50

Picking up in Boston where he left off with Detroit, Ganzel was tagged to back up catcher Bennett for the 1889 campaign. Even in his role as a part-time player, the media wasted no time heaping praise on Ganzel. “Wherever we go all look with envy at our backstops,” boasted the Boston Herald of Ganzel and his counterpart Bennett.51 Too valuable to sit on Boston’s bench solely as a backup receiver, however, Ganzel was given the opportunity to display the versatility he exhibited in Detroit a year earlier. “Charlie Ganzel would make a great fielder if ever there became need for him to take a position in the outfield,” opined the Herald quite presciently in April. Over the course of the season he played in 73 of Boston’s 128 games, primarily splitting time at catcher and outfield, while even making several appearances as an infielder. “Ganzel doesn’t make much noise and his modesty rather obscures his brilliancy, yet he is becoming one of the great all-round players of the League,” wrote Sporting Life.52 Although lauded for his super-sub skills and called a “prime favorite here by his quiet and unassuming way of going about his business,” offensively Ganzel finished the season with the second-place Beaneaters in typical middling fashion, hitting .265 with one home run and 43 RBIs.53

While Ganzel enjoyed a successful first season on the diamond with Boston, trouble had been brewing off the field in the NL during the 1889 campaign. The Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players – a players association originally formed in 1885 – grew increasingly disenchanted with perceived low pay and unfair treatment by team owners. This led to the Brotherhood’s formation of the Players’ League, to begin play in the 1890 season. This upstart major league succeeded in snaring a significant number of star players away from the NL and American Association to create a strong rival for these more established leagues. As Ganzel was a member of the Brotherhood and thus a likely candidate to jump ship as some of his teammates had done, desperate Players’ League representatives went to the lengths of attempting to track him down in a remote area of California while he was on a hunting trip to hurriedly persuade him to sign a contract. Their search proved too late, however.54 Ganzel – although supportive of the Brotherhood – had already signed with the Beaneaters reportedly as a “matter of honor,” owing to a verbal agreement he made with the team committing him to a two-year deal when he originally signed.55 Not all saw his actions as honorable; Ganzel received his share of criticism for not jumping to the Players’ League. “Charley has lost many friends by his actions in this matter. The day will come when he will regret deserting his brothers,” wrote one newspaper at the time.56

Ganzel did indeed honor his commitment to the Beaneaters, performing in his usual “quiet and gentlemanly manner” on the field for the 1890 campaign.57 Despite being named team captain at the beginning of the season, he appeared in his fewest games since 1885.58 Having a typically mediocre year at the plate, Ganzel still provided value in flexing between his normal backup catcher role and the outfield. With his contract fulfilled at season’s end, rumors swirled that Ganzel might take over as skipper of Boston’s Players’ League club – even though some in the Brotherhood considered him a deserter for remaining in the NL for the 1890 season.59 Any speculation was put to rest, however, when the Players’ League folded after its one and only season.

Remaining with the Beaneaters, Ganzel continued as a model of consistency behind the plate, with the Boston Globe writing that he had “caught admirably” during his time in Boston.60 Although still used in a backup role behind Bennett and megastar King Kelly in contributing to Boston’s winning three consecutive pennants (1891-1893), Ganzel was deemed a “favorite with the players as well as the public.”61 And one newspaper later recalled how his skills as a backstop “lifted [future Hall of Fame pitchers] Kid Nichols and John Clarkson to greater heights of repute.”62 Possibly around this time period, he and Kelly – a noted trickster – were reportedly involved in a legendary play that spurred a rule change involving in-game substitutions. The November 28, 1894, edition of the New Castle (Pennsylvania) News provided Charlie Bennett’s recollection of the event. “During a game one day, [Kelly] sat on the bench and Ganzell [sic] was behind the bat. A foul fly was popped up, out of Ganzell’s reach, when quick as a flash Kel ran forward, ordered Ganzell out of the game, caught the ball, and then ordered the umpire to declare the batter out. He maintained with a great deal of force, that he had as much right to order Ganzell out of the game, while a ball was in the air, as at any other time during the progress of the game. However, the decision went against him,” recalled Bennett.63 Several versions of this story have been in circulation over the years, but whether the event actually occurred is still in question for lack of indisputable evidence.64

Ganzel finally got his opportunity to become Boston’s unequivocal regular catcher in 1894 after a tragic accident that befell his longtime catching counterpart Bennett. In January Bennett – with whom Ganzel had maintained a “most pleasant” relationship – lost both legs after slipping under a train while attempting to board.65 In reflecting on Bennett in a later interview, Ganzel called the venerable star “the greatest catcher who ever put on a glove.”66 Unable to fully capitalize on his opportunity as the club’s regular backstop, however, Ganzel was released by Boston in midseason. “Charlie is a good fellow and has been an excellent player until this season, but his playing thus far has not been up to the standard we require, and after giving him all the opportunity in the world to better his play, which he has not done, he has been given his release,” explained Beaneaters manager Frank Selee.67 After Ganzel received offers from several teams – including one from Cincinnati that he seriously considered – Boston decided to re-sign him less than two weeks after releasing him. “Yes, we re-signed Charley because we really believe he will play good ball for us,” said Beaneaters President Arthur Soden.68 Soden’s hunch proved correct, as Ganzel rebounded and arguably put together the best year of his career. The Brooklyn Eagle summed up Ganzel’s season thusly: “The Boston club made no mistake when it got Charlie Ganzel back. He is playing in his old Detroit form and that is saying a good deal.”69 In his 70 games, Ganzel hit .278 with 3 home runs and 56 RBIs – all career highs.

After another solid season in 1895 as the regular backstop for Boston where his play was described as “A 1,” Ganzel found himself out of action for several weeks during the 1896 season with a serious leg injury suffered when he was spiked during a game against Washington in June.70 Supplanted as the regular catcher by promising 24-year-old rookie Marty Bergen, Ganzel played in only 47 games in 1896 – his second fewest since his initial NL campaign. The acquisition of Bergen essentially spelled the end for the aging veteran, with Boston now in the midst of a rebuilding process.71 Hanging on in a little-used backup role to Bergen for the 1897 season, Ganzel added one more NL pennant under his belt – his fourth with the Beaneaters and fifth overall – but did not enjoy his lack of playing time along the way. “Charlie Ganzel has not caught for so long even the bleacherites fail to recognize him when he appears in uniform to warm up the infielders or catch the pitching prior to the game. Charlie is sore at Selee for playing Marty Bergen continuously, and thinks he is given to playing favorites,” wrote the Washington Evening Times.72 Released by Boston after the 1897 season, Ganzel retired at age 35 after 14 seasons in the big leagues with a .259 career batting average, 10 home runs, and 412 RBIs in 787 games.

Ganzel remained in the Boston area after his retirement. He also remained very close to the game, playing for several local semipro teams, including the Carters of Franklin, Milford, Newburyport, and Worcester.73 Ganzel also coached the Williams College squad for several seasons in the late 1890s and early 1900s, and occasionally could even be found umpiring in college, semipro, and big-league contests.74 When not on the diamond, he had a successful business career as a traveling salesman in the garment industry. Ganzel was a member of the Freemasons, and volunteered his time with the young men’s Makaria Bible class organization at Bethany Congregational Church in Quincy, Massachusetts.75

Ganzel also spent time raising a family with his wife, Alice, whom he had married in 1885. From 1885 to 1910, the couple had nine children: Arthur, Rupert, Gladys, Wesley, Lloyd, Charles, Foster, Alice, and John. One-year-old Arthur died in 1886, and 5-year-old Alice died in 1914 of diphtheria. “The only things I now have to live for are my wife and my Bible. And I still retain my faith in God,” Ganzel confessed after the passing of his young daughter.76 On a happier note, Ganzel’s sons Wesley and Foster carried on the family’s tradition of finding success in baseball. Wesley made it to the minor-league level. And Foster – better known as Babe – played two seasons with the Washington Senators. Babe’s 1927 major-league debut – 43 years after his father’s debut in the Union Association – resulted in the longest span ever between the first big-league games by a father and son.

Around 1912, Ganzel was diagnosed with cancer. The ensuing long battle with the disease included several surgeries and sapped the family’s finances. In recognizing that Ganzel was “under sentence of death,” Boston newspaper editors and baseball executives formed a committee to raise funds to assist the struggling family.77 In a testament to Ganzel’s popularity and character, over $1,000 was raised for a man called “one of the cleanest, gamest and most honorable players ever connected with baseball.”78 On April 7, 1914, “after one of the most stubborn fights any man had ever made against that most dreaded disease,” Ganzel died of epithelioma of the lower lip and jaw – on his brother John’s 40th birthday and only two months after his daughter Alice’s death.79 He was buried at Mount Wollaston Cemetery in Quincy.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed Ganzel’s file at the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York; Ancestry.com; Baseball-Reference.com; Chronicling America; GenealogyBank.com; NewspaperArchive.com; Newspapers.com; and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Detroit Team Was the Best,” Detroit Free Press, April 3, 1904: 14.

2 Marty Appel, Pinstripe Empire: The New York Yankees from Before the Babe to After the Boss (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 26; Keith Howard, “The Ganzel Brothers: Baseball Legends,” Kalamazoo Public Library, kpl.gov/local-history/biographies/ganzel-brothers.aspx, June 2015, accessed August 16, 2017.

3 “In This Family of Fifty-Two There Has Never Been a Death,” Detroit Free Press, June 24, 1906: 18.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 “Ganzel Family Reunion,” Racine Journal, November 6, 1906: 1.

7 “Racine Boys Make Good in the Baseball World,” Racine Journal-News, August 23, 1915: 6; “To an Old Time Star,” Racine Journal-News, February 9, 1914: 9.

8 Peter Herman, “Baseball History of Racine Related,” Racine Journal-Times, February 23, 1941: 8.

9 “Oshkosh Is Third,” Oshkosh (Wisconsin) Northwestern, August 22, 1887: 3.

10 “Name 10 Athletes to ‘Hall of Fame,’” Racine Journal-Times, May 9, 1969: 26.

11 “Detroit Team Was the Best.”

12 “The Browns Have a Walk Away with the Hudsons – Score 25 to 5,” St. Paul Globe, July 26, 1883: 6.

13 “The Red Caps Defeat the Brown Stockings in a Score of Three to Ten,” St. Paul Globe, September 16, 1883: 6. The box score in this newspaper suggests that Charlie’s brother George appeared in at least one game for Minneapolis in 1883. Because reports of the day tended to refer to players only by their surnames, it is possible that some of the highlights credited to Charlie above in fact belong to his brother. This is highly unlikely, however, due to Charlie’s exploits for the Brown Stockings being well-documented, coupled with George’s youthfulness at the time (he was 17 years old).

14 Stew Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota: The Definitive History (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2006), 17.

15 “One for Stillwater,” St. Paul Globe, April 28, 1884: 6.

16 “First of the Season,” St. Paul Globe, June 10, 1884: 2; “Threshed Our Sister,” St. Paul Globe, June 24, 1884: 3.

17 “Detroit Team Was the Best.”

18 Ibid.

19 “Three Famous Old Players, Ganzel, Nash and M’Carthy, Now Boston Business Men,” Boston Post, August 10, 1902: 6.

20 “Yesterday’s Sports,” St. Paul Globe, October 18, 1884: 5.

21 “News Summary,” Phillipsburg (Kansas) Herald, November 8, 1884: 6.

22 “Three Famous Old Players, Ganzel, Nash and M’Carthy, Now Boston Business Men.”

23 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, February 10, 1886: 5.

24 Ibid.

25 “Piling Up Victories,” Detroit Free Press, June 16, 1886: 5.

26 “A Farce at Recreation Park,” Philadelphia Times, May 29, 1886: 2.

27 “The Local Season,” Sporting Life, September 29, 1886: 5.

28 “Base Ball Notes,” Philadelphia Times, June 3, 1886: 3.

29 “Detroit Team Was the Best.”

30 “Fresh Base Ball Gossip,” Philadelphia Times, May 16, 1886: 2.

31 “At Home Again,” Sporting Life, June 23, 1886: 1.

32 “Piling Up Victories.”

33 “Detroit Wild Over Ball,” Philadelphia Times, June 20, 1886: 11.

34 “Detroit, 10; St. Paul, 9,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1887: 3; “Baseball’s Honor Roll Has Famous Batteries,” Detroit Free Press, September 12, 1909: 16.

35 Roy Kerr, Big Sam Thompson: Baseball’s Greatest Clutch Hitter (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2015), 64.

36 “The Champions,” Boston Globe, October 11, 1887: 3.

37 Jean-Pierre Caillault, The Complete New York Clipper Baseball Biographies (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 257.

38 “Our Champions,” Detroit Free Press, October 25, 1887: 4.

39 “A Grand Finale,” Detroit Free Press, October 25, 1887: 2.

40 “Detroit Team Was the Best.”

41 “Detroit Dotlets,” Sporting Life, July 4, 1888: 5.

42 Caillault, The Complete New York Clipper Baseball Biographies, 257.

43 Kerr, 79.

44 “$30,000 for the Detroits,” Boston Herald, October 10, 1888: 5.

45 “Bostons Are the Champions,” Boston Herald, October 19, 1888: 5.

46 “The Detroit-Boston Deal,” Boston Herald, November 13, 1888: 5.

47 “Sporting Matters,” Pacific Commercial Advertiser (Honolulu), October 29, 1888: 2.

48 “Bostons Are the Champions.”

49 “Base Ball Chat,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 16, 1888: 8; “A $50,000 Ball Club,” Philadelphia Times, November 4, 1888: 14.

50 Jean-Pierre Caillault, A Tale of Four Cities: Nineteenth Century Baseball’s Most Exciting Season, 1889, in Contemporary Accounts (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 7.

51 “Boston Is Rated Second,” Boston Herald, April 15, 1889: 5.

52 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, July 3, 1889: 4.

53 “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, May 22, 1889: 7.

54 Robert B. Ross, The Great Baseball Revolt: The Rise and Fall of the 1890 Players League (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 121-123.

55 “‘Spiders’ in Town,” Boston Globe, May 16, 1890: 7; “The Triumvirs’ Big Trio,” Boston Herald, December 13, 1889: 10.

56 “From Celeryville,” clipped newspaper article from Ganzel’s file at the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, January 29, 1890.

57 “Clubs the Policemen Favor,” Boston Herald, April 6, 1890: 23.

58 “All Disabled,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 19, 1890: 2.

59 “News Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, September 20, 1890: 5.

60 “The Champions of ’92,” Boston Globe, October 5, 1891: 11.

61 Ibid.

62 Associated Press, “Catching as Baseball Art Is No More; Ancients Were Far Better, Critic Says,” Battle Creek (Michigan) Enquirer, July 8, 1929: 13.

63 “A Talk with Charlie Bennett,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, November 28, 1894: 8.

64 Sarah Wexler, “‘Kelly Now Catching’: King Kelly and Baseball’s Substitution Rules,” Hardball Times, fangraphs.com/tht/kelly-now-catching-king-kelly-and-baseballs-substitution-rules/, December 4, 2015, accessed October 26, 2017.

65 “Detroit Team Was the Best.”

66 Ibid.

67 “Catcher Ganzel Released,” Boston Advertiser, July 25, 1894: 5.

68 “Ganzel to Remain,” Boston Advertiser, August 6, 1894: 2.

69 “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 6, 1894: 4.

70 “Personal,” Sporting Life, June 29, 1895: 6; “Badly Spiked,” Kalamazoo Gazette, June 27, 1896: 1.

71 Bill Felber, A Game of Brawl: The Orioles, the Beaneaters, and the Battle for the 1897 Pennant (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 44.

72 “Diamond Dust,” Washington Evening Times, August 26, 1897: 6.

73 “On the Line,” Boston Herald, June 30, 1900: 4; “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, May 6, 1904: 5; “Lynn, 16; Newburyport, 0,” Boston Herald, May 3, 1903: 7; “News in the Sporting World,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, April 15, 1898: 3.

74 “Baseball Brevities,” Pittsburg Press, April 27, 1898: 6; “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, March 24, 1900: 8; “Coaching Players,” Sporting Life, April 12, 1902: 12; “Not a Run for Brown,” Boston Herald, May 8, 1903: 9; “Lynn Now Leader of the N.E. League,” Boston Journal, May 20, 1909: 9; “Giants Easy for Boston,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 15, 1901: 8.

75 “Spokes from the Hub,” Sporting Life, December 1, 1906: 3; “The Obit for Charlie Ganzel,” The Deadball Era, thedeadballera.com/Obits/Obits_G/Ganzel.Charlie.Obit.html, accessed October 25, 2017.

76 “Minneapolis Globules,” St. Paul Globe, October 12, 1886: 3; “Charlie Ganzel’s Little Daughter Dies in Hospital,” Boston Herald, February 15, 1914: 4.

77 “Famous Catcher Very Ill,” Boston Post, January 7, 1914: 10.

78 “The Obit for Charlie Ganzel”; “Famous Catcher Very Ill.”

79 “The Obit for Charlie Ganzel.”

Full Name

Charles William Ganzel

Born

June 18, 1862 at Waterford, WI (USA)

Died

April 7, 1914 at Quincy, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.