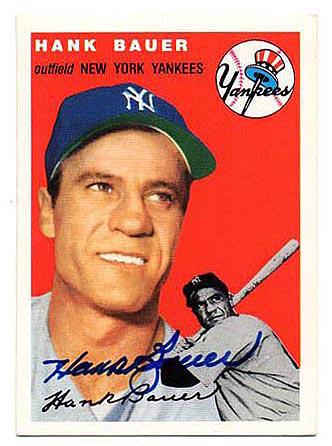

Hank Bauer

Right fielder Hank Bauer was a mainstay of the Casey Stengel–Yogi Berra Yankee dynasty who sparkled in the World Series spotlight. In the final game of the 1951 Series his bases-loaded triple broke a tie and gave the Yankees a 4-1 lead. After the Giants narrowed the margin to 4-3 in the ninth, with the tying run on second base, Bauer made a sliding catch of a sinking line drive for the last out.

Right fielder Hank Bauer was a mainstay of the Casey Stengel–Yogi Berra Yankee dynasty who sparkled in the World Series spotlight. In the final game of the 1951 Series his bases-loaded triple broke a tie and gave the Yankees a 4-1 lead. After the Giants narrowed the margin to 4-3 in the ninth, with the tying run on second base, Bauer made a sliding catch of a sinking line drive for the last out.

He hit safely in a record 17 consecutive World Series games — all seven in the 1956 and 1957 classics and the first three games in 1958. After the Braves’ Warren Spahn ended his streak in Game Four, he homered off Spahn in the sixth game. It was his fourth home run in that Series, a record he shared at the time with Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Duke Snider.

Before joining the Yankees, Bauer won two Bronze Stars and two Purple Hearts as a marine in World War II. After the Yankees he managed the Baltimore Orioles to their first World Series championship.

He was tough and looked it. Sportswriter Jim Murray said Bauer had “a face like a clenched fist.”1 He grew up watching the St. Louis Cardinals Gashouse Gang and played the game their way: all-out. Before Pete Rose was born, Bauer learned from the Cardinals’ Enos Slaughter how to run hard to first when he drew a walk. “It’s no fun playing if you don’t make somebody else unhappy,” he said. “I do everything hard.”2

Henry Albert Bauer was accustomed to hardship. His parents, John and Mary, were immigrants from Austria-Hungary. John lost a leg in a factory accident, then worked as a bartender. “My dad made sixty bucks every two weeks,” Henry recalled. “My oldest sisters used to bring home support.”3 Henry was the youngest of nine children, born in East St. Louis, Illinois, on July 31, 1922. “He was a real dead-end kid,” his brother Joe said, “always going around with a bloody nose.”4

Two of the Bauer boys went into baseball. Herman signed with the White Sox as a catcher and was a top prospect in Double A, the highest minor league level, when he was drafted into the army in 1941. Henry said the older brother was the family’s best player, but he never got a chance to prove it. Herman was killed in action in France in 1944.

Herman helped Henry get a professional tryout in 1941, and the 18-year-old joined the Class D Oshkosh Giants as a 160-pound “shrimp,” as he recalled it.5 Then he followed Herman into military service, enlisting in the Marine Corps in January 1942.

Bauer was shipped to the Pacific Theater and promptly came down with malaria. He endured 23 attacks of the disease during his four years in the Marines. He also survived jungle combat on Pacific islands. He earned his first Bronze Star and Purple Heart on Guam, where he was hit by shrapnel. His second medals came in the fierce battle for Okinawa. Only six of the 64 men in Sergeant Bauer’s platoon survived the fight. When shrapnel from an artillery shell ripped a hole in his left thigh, he told a buddy, “There goes my baseball career.”6

Bauer carried bits of shrapnel in his back for the rest of his life. He recovered from his wounds, but gave up on baseball and found a job as an ironworker. Yankee scout Danny Menendez, who remembered him from before the war, signed him to a Class B contract in 1946. The teenage shrimp had grown to a powerful 6-foot, 196-pound man.

Bauer tore through the Yankee farm system, batting over .300 all three years. He was moved to the outfield because of his speed and strong arm. At the top farm club in Kansas City in 1947, he met Charlene Friede, who was general manager Lee MacPhail’s secretary. The players had to pass her desk to pick up their paychecks. “The whole first year all I did was say hello,” Bauer said. “In 1948 I asked her for a date.”7 After that leisurely courtship, they were married the next year.

He hit .305 for Kansas City in 1948 with 23 home runs and 26 stolen bases before the Yankees called him up for a September audition. Batting third between Tommy Henrich and Joe DiMaggio, he singled in his first three plate appearances.

After finishing third in 1948, the Yankees brought in Stengel as manager and began working young players into the lineup. Bauer, a 26-year-old rookie, was one of six position players his age or younger. That was partly out of necessity, because the club was hit with an epidemic of injuries in 1949. Bauer played center field early in the season while DiMaggio was recovering from surgery on his heel. He batted .272/.354/.432 in 103 games.

The Yankees won the 1949 pennant by beating Boston in the last two games of the season, then defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers in the World Series. It was the first of five consecutive Series championships, a run unmatched in baseball history.

Bauer, a right-handed batter, was primarily a platoon player in his first three seasons. (It is a misconception that he was platooned throughout his career.) He often shared time with Gene Woodling, although Woodling played left field and Bauer right. They were close friends, and each man believed he should be playing every day. Stengel “used to keep us both mad,” Bauer said, “and once we got in there we busted our butts to stay in the lineup.”8

During the Yankees’ five-year championship streak, Bauer batted .298 with an OPS over .800. He won a regular spot in the lineup, though Stengel sat him down against certain tough right-handers. In 1953 Stengel installed him as the leadoff hitter; his on-base percentage topped .350 for his first 10 full seasons. He was the American League’s starting right fielder in the 1952-53-54 All-Star Games.

While Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra were the brightest Yankee stars, Bauer became a Stengel favorite not only for his hard-nosed play but also for the results. “Too many people judge ball players solely by a hundred runs batted in or a three hundred batting average. I like to judge my players in other ways,” the manager said, pointing to Bauer. “Like the guy who happens to do everything right in a tough situation.”9

He also emerged as a team leader. Mantle, a rookie in 1951, said Bauer “taught me how to dress, how to talk, and how to drink.” But Bauer wasn’t shy about calling out Mantle and his running mates for their strenuous night life, which sometimes left them in less than perfect playing condition. Pitcher Whitey Ford remembered Bauer pinning him against a wall and growling, “You’re messing with my money.”10

The most infamous moment of Bauer’s career happened at a birthday celebration for Billy Martin on May 15, 1957. Several Yankees and some of their wives went to the Copacabana night club to see Sammy Davis Jr. perform. Later testimony revealed that at least one drunken member of a bowling team taunted the African American entertainer with racial slurs, and Bauer told him to pipe down. What came next was in dispute. The loudest drunk bowler wound up on a bathroom floor with a broken nose and bloody face. He said Bauer had slugged him, but Bauer insisted, “I know it was not me, and it was not Billy Martin.”11 The truth remained a mystery for six decades, until a former Copa bouncer, 88-year-old Joey Silvestri, claimed he had thrown the punches.12

One tabloid headline screamed “Bauer in Brawl.” The injured man swore out a warrant for Bauer’s arrest, and he was fingerprinted and booked. After Berra testified, “Nobody never hit nobody nohow,” a grand jury threw out the charges.13 The victim in the case turned out to be Martin, whose crime was having a birthday party. He was soon traded to Kansas City. General manager George Weiss had been looking for an excuse to get rid of him, believing he was a bad influence on his pal Mantle.

Bauer had notched career highs in 1956 with 26 home runs and 84 RBIs, but his batting average slipped as he reached his mid-30s. Still, Stengel defended him: “He hits the long ball and he gets the hit when you need it. He’s the hardest-running thirty-six-year-old I’ve ever seen, and he gives you every ounce of his energy for nine full innings every day.”14

The Yanks won nine pennants and seven World Series in Bauer’s first 10 full years. As the roster turned over from the prewar DiMaggio generation to the Mantle era, only Bauer and Berra played in all nine Series. Bauer’s 53 games in the Fall Classic are tied for fourth all-time, his 46 hits tied for fifth. (Berra, who played in 14 World Series, leads in both categories.)

After the club sank to third place in 1959, Bauer was traded to the Kansas City Athletics as part of a deal for a younger right fielder, Roger Maris. Bauer heard of the trade on the radio. He thought he deserved better.

The Athletics were a dumping ground for unwanted Yankees. They were also the American League’s doormat, only once finishing as high as sixth in their 13 years in Kansas City. In June 1961 new owner Charles O. Finley made Bauer the manager with Finleyesque flair. In mid-game he had the stadium public address announcer say, “Hank Bauer, your playing days are over. You have been named manager of the Kansas City A’s.”15

Bauer always said he had no ambition to manage, but he agreed to give it a try. He was a popular choice. He had settled his family in Kansas City, Charlene’s hometown. The club finished ninth in the 10-team league in 1961, besting only the expansion Washington Senators. The volatile Finley dictated lineup changes and meddled in personnel decisions. Bauer said, “The only bad thing about Charlie is, he hires you to do a job but he wants to do it for you.”16 After a 90-loss season in 1962, Bauer resigned before Finley could fire him.

He found work as a coach for the Baltimore Orioles, whose general manager, Lee MacPhail, had been a Yankee executive and his wife’s boss. The Orioles, after contending for the pennant in 1960 and 1961, dropped to seventh place in 1962 under new manager Billy Hitchcock. The club rose to fourth in 1963, but it was a distant fourth, and Hitchcock was fired. Bauer replaced him with only a one-year contract.

The rap against Hitchock had been that he let the players walk all over him. Bauer would have none of that. “I ain’t running no popularity contest,” he said.17 He enforced only a few rules; they boiled down to “play hard and don’t embarrass yourself or the ball club.” First baseman Boog Powell said, “He just expected you to act like a man, nothing less.”18 But one player called him “Hitler,” though he may have been joking. “[H]e had a raspy voice and scared the hell out of everyone,” pitcher Milt Pappas recalled. “Underneath he was the nicest guy in the world.19

With a dramatically overhauled team, adding shortstop Luis Aparicio, first baseman Norm Siebern, and young pitchers Wally Bunker and Dave McNally, Bauer led the Orioles to the brink of the 1964 pennant. The club held first place into September, when the Yankees won 15 of their last 19 to snatch away the flag. Baltimore, with 97 victories, finished third, and The Sporting News named Bauer Manager of the Year. After another third-place finish in 1965, the Orioles made the move that put them over the top.

MacPhail resigned after the season to become the brain of the clueless new baseball commissioner, William Eckert. He left his successor, Harry Dalton, a proposed trade with Cincinnati: Pappas and two others for Frank Robinson, the slugging former National League Most Valuable Player. Bauer was reluctant to make the deal because Pappas was one of the anchors of his pitching staff and Robinson carried a reputation as a troublemaker; he had once been caught with a concealed handgun.20

Dalton pulled the trigger anyway and brought the Orioles their first championship. Bauer was never so happy to be wrong. “Frank was the big guy, the inspiration, the leader,” he said later. “He was the difference.”21 Robinson won the Triple Crown, leading the AL with 49 home runs, 122 RBIs, and a .316 batting average, and became the only player to win MVP honors in both leagues.

“We had an awesome, nasty lineup,” Powell said. “We pounded on people. We rolled. And we had a ton of fun.”22 With Powell, Frank and Brooks Robinson, and Curt Blefary supplying the power, the club scored the most runs in the AL. A young starting rotation, headed by breakout star Jim Palmer, got the publicity, but the bullpen did the heavy lifting as the starters completed only 23 games. Bauer had two relief aces in Stu Miller and knuckleballer Eddie Fisher supported by journeymen Moe Drabowsky and Eddie Watt. The Orioles took over first place in June and finished nine games ahead of second-place Minnesota.

Still, they were underdogs in the World Series against the Los Angeles Dodgers, who had Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale to quiet the Baltimore bats — or so the smart money said. Before Game One Jim Russo, the Orioles’ advance scout, gave the team a discouraging description of the Dodger pitching staff. “If these guys are that good,” Bauer snarled, “we got no chance. Meeting over.”23 He knew his team didn’t need a pep talk.

In the first inning, the two Robinsons rocked Drysdale with back-to-back home runs. So much for invincible. Drabowsky relieved McNally, pitching 6 2/3 scoreless innings, giving up one hit, and striking out 11 in a 5-2 victory. For the rest of the Series the Baltimore bullpen sat at ease while the young starters took charge. The Dodgers didn’t score another run. Palmer, Bunker, and McNally reeled off consecutive shutouts to give the Orioles a sweep and a trophy.

“Great pitching and great defense did it,” Bauer said in the raucous clubhouse, as his players sprayed shaving cream instead of champagne. “Personally, I never dreamed of a four-game blitz. I figured six or seven and we’d win — but never four games. I didn’t think we’d get this kind of pitching — but then I don’t think anybody else did.”24 He won his second Manager of the Year award.

The triumph of 1966 turned sour the next year. Sore arms crippled the pitching staff, and Frank Robinson suffered double vision after a collision when he broke up a double play. While the injuries could explain why the Orioles stumbled to a 76-85 record and sixth place, GM Dalton put some of the blame on the manager. Dalton thought Bauer was too much of a hands-off manager — put ’em on the field and let ’em play. Frank Robinson described him as a veteran’s manager, but the Orioles were a young team and “he was tough on the young guys.”25

After the season Bauer said Dalton invited him to resign, but the manager wouldn’t walk away from the year left on his $50,000 contract. Owner Jerold Hoffberger didn’t want to pay him not to manage, so Bauer kept his job, but Dalton fired three of his four coaches. One of the new coaches was Earl Weaver, a young manager in the Baltimore farm system who was a Dalton favorite. “I didn’t want him around,” Bauer said later.26

“I think everyone thought that Weaver would be the manager sooner or later, simply because Weaver was Dalton’s guy,” Brooks Robinson said.27 It was sooner. At the 1968 All-Star break the Orioles stood in third place, 10½ games behind. Bauer was at home in Kansas City mowing his lawn when Dalton called from the airport and asked to stop by. Bauer hung up and told Charlene, “I’m going to be fired.” Dalton arrived in a cab and left the meter running while he came inside.28 When he got back in the cab a few minutes later, Weaver was the Orioles manager.

“Somebody had to be the fall guy,” Bauer said.29 Twenty-one months after bringing a championship to Baltimore, he was unemployed.

Bauer’s popularity in his adopted hometown made him a natural choice to manage Kansas City’s new expansion team, the Royals, in 1969. More likely, his connection to the bad old days of the Kansas City A’s killed his chances.

Instead he signed on to manage the Oakland A’s — back under Charlie Finley’s thumb. “Look, I didn’t have much of a choice,” he explained. “I was out of a job.”30 He was the ninth manager in the nine years Finley had owned the club.

The A’s were now a team of young stars on the rise: Reggie Jackson, Catfish Hunter, Sal Bando, among others. They charged into the race for the Western Division title and actually spent 35 days in the unfamiliar altitude of first place. But they sputtered in September, and Bauer didn’t last the season. Finley fired him when the A’s fell out of the race.

At 47, Bauer hoped for another chance. His friend Whitey Herzog, farm director of the Mets, hired him to manage the Triple-A club at Norfolk, Virginia, in 1971. But after two seasons, and a Sporting News Minor League Manager of the Year award, no big league team had called.

Throughout their 23 years of marriage, Hank and Charlene had spent most summers apart. She maintained a stable life in the Kansas City area for their four children, Hank, Herman, Kelly, and daughter Bernadine. Now the breadwinner came home to run his liquor store in suburban Prairie Village, with plenty of time for hunting and fishing. He took up golf, then gave up golf. “Only time I ever hit to right field in my life was on that golf course,” he said.31

After selling the store in 1978, Bauer joined the Yankees as a major league scout, keeping tabs on other AL teams when they came to Kansas City. In retirement he occasionally worked autograph shows and fantasy camps. When he reached his 80th birthday, he said, “I told my doctor I owe my longevity to scotch and cigarettes. That didn’t go over too well.”32 He died of lung cancer at 84 on February 9, 2007.

“I wasn’t blessed with natural ability like a lot of ball players,” Bauer said. “I had to work like hell. I was blessed with a good arm and a good pair of legs. I could run. But for the other skills in baseball I worked my butt off.”33 He has no plaque in Monument Park, but Bauer always considered himself a Yankee. “The Yankee logo,” he said, “is like a degree from Harvard.”34

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Additional Sources

Bedingfield, Gary. “Hank Bauer.” Baseball in Wartime. http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/bauer_hank.htm.

Bedingfield, Gary. “Herman Bauer.” Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice. http://www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/biographies/bauer_herman.html.

Photo Credit: The Topps Company

Notes

1 Steven Travers, The Poet: The Life and Los Angeles Times of Jim Murray (Washington: Potomac Books, 2013), 208.

2 “Old Potato Face,” Time, September 11, 1964: 88.

3 Peter Golenbock, Dynasty (Inglewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1975), 102.

4 “Old Potato Face,” 88.

5 Hank Bauer interview by Irwin Bergman, June 26, 1991, SABR Oral History collection.

6 “Famous Marine Friday: Hank Bauer,” Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego Museum, May 8, 2015. https://www.facebook.com/usmchistory/posts/854056001347889, accessed February 15, 2017.

7 Douglas Brown, “Thick-Skinned, Blunt, Relaxed, Smiling — Hank Bauer,” Baltimore Sun Magazine, April 12, 1964: M10.

8 Bergman interview.

9 Golenbock, 101.

10 “Old Potato Face,” 89.

11 Phil Rizzuto with Tom Horton, The October 12 (New York: Forge, 1994), 114.

12 David Margolick, “63 Years Later, a Confession in a Legendary Yankees Scandal,” New York Times, June 19, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/19/nyregion/1957-yankees-brawl-copacabana-silvestri.html.

13 “Old Potato Face,” 89.

14 American Weekly, September 7, 1958, in Bauer’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

15 Mark Armour, “Charlie Finley,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/6ac2ee2f, accessed May 7, 2017.

16 Rich Marazzi, “For Hank Bauer, the World Series was his stage,” Sports Collectors Digest, February 14, 1997: 91.

17 John R. McDermott, “Toughest Bird in Baltimore,” Life, July 8, 1966: 48A.

18 Mike Klingaman, “Manager ‘was like a father,’” Baltimore Sun, February 10, 2007, in HOF file.

19 John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: An Oral History of the Baltimore Orioles (New York: Contemporary Books, 2001), 141.

20 Frank Robinson and Berry Stainback, Extra Innings (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988), 50.

21 Golenbock, 105.

22 Eisenberg, 173.

23 Jane Leavy, Sandy Koufax (New York: HarperCollins, 2002), 236.

24 Bob Addie, “Dodgers Set World Series Records for Futility,” Washington Post, October 10, 1966: C1.

25 Eisenberg, 185.

26 Gordon Beard, “Hank Bauer Says Orioles Sought His Resignation At End of 1967,” Associated Press-Baltimore Sun, July 12, 1968: C1.

27 Eisenberg, 185.

28 Jack Etkin, “Orioles to give Bauer a lasting tip of the cap Saturday,” Kansas City Star, June 12, 1990: C-3.

29 Beard.

30 Bob Maisel, “The Morning After,” Baltimore Sun, October 5, 1968: B-3.

31 Randy Covitz, “Former Ballplayer Hank Bauer Dies at 84,” Kansas City Star, February 9, 2007. http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/kansascity/obituary.aspx?n=Hank-Bauer&pid=86373905, accessed February 15, 2017.

32 Ed Randall, More Tales from the Yankee Dugout (Kingston, New York: Sports Publishing, 2002), 118.

33 Golenbock, 104.

34 Dave Anderson, “Two of the Best Are Not Two of a Kind,” New York Times, February 12, 2007: D4.

Full Name

Henry Albert Bauer

Born

July 31, 1922 at East St. Louis, IL (USA)

Died

February 9, 2007 at Lenexa, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.