Bud Souchock

Late on Monday afternoon, August 25, 1952, a classic baseball scene occurred at New York’s storied Yankee Stadium. As the shadows lengthened on the field, a crowd of 13,442 watched as the last-place Detroit Tigers came to bat in the top of the seventh inning, trying to break a scoreless tie with the league-leading New York Yankees. Facing rookie left-hander Bill Miller, Detroit’s Steve Souchock stepped into the batter’s box and got ready. The previous batter, right-handed-hitting Walt Dropo, the big slow-moving first baseman, stood at second base after doubling down the left-field line.

Late on Monday afternoon, August 25, 1952, a classic baseball scene occurred at New York’s storied Yankee Stadium. As the shadows lengthened on the field, a crowd of 13,442 watched as the last-place Detroit Tigers came to bat in the top of the seventh inning, trying to break a scoreless tie with the league-leading New York Yankees. Facing rookie left-hander Bill Miller, Detroit’s Steve Souchock stepped into the batter’s box and got ready. The previous batter, right-handed-hitting Walt Dropo, the big slow-moving first baseman, stood at second base after doubling down the left-field line.

Souchock, 33, a right-handed-batting outfielder in his fifth major-league season and his second with Detroit, could hit with power, but he concentrated on making contact. Yankees manager Casey Stengel signaled not to walk the hitter, Miller delivered, and Detroit’s ace utilityman singled down the left-field line. Before Gene Woodling’s throw could reach the plate, Dropo came around to score what proved to be the game-winning run. Bolstered by the 1-0 lead, Tiger fireballer Virgil Trucks, bearing down with his fastballs and hard sliders, completed his second no-hitter in 1952 (he had topped the Washington Senators, 1-0, on May 15), although he compiled just a 5-19 record for the season.

Souchock’s single, like most of the hits during his career, was not the biggest story of the game. Instead, New York’s Phil Rizzuto hit a bouncer to shortstop Johnny Pesky in the third, and Pesky, who lost the handle on the ball before regaining control, threw low and late to first base. The official scorer, veteran New York sportswriter John Drebinger, immediately ruled it an error. Other scribes in the press box maintained that the ball stuck in the webbing of Pesky’s glove, making it technically a hit. Drebinger consulted with Pesky between innings, and Johnny said he “messed it up.”

Drebinger changed his ruling to error, but the change was not announced until after the Tigers moved ahead, 1-0. The crowd, anticipating a no-hitter, roared with approval, and Trucks mowed down the final nine batters. The game was hardly perfect, as three Yankees got aboard, two on errors, and Trucks also walked Mickey Mantle after Rizzuto reached base in the third.

Detroit’s no-hit 1-0 triumph over the Bronx Bombers was one of the team’s most memorable games in a disappointing season. Finishing with a 50-104 record, the pitching-poor Tigers, led by the 12-17 record of Ted Gray, fell to the American League cellar for the first time in franchise history. The powerhouse Yankees (95-59) won the pennant by two games over the Cleveland Indians, and New York defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1952 World Series.

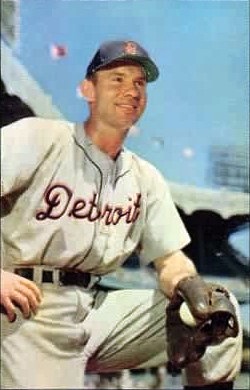

Pictured celebrating afterward with Trucks and Dropo, Souchock was an unlikely Tiger hero. Suffering on-again, off-again lower back pain from a deteriorating disk, the first baseman-turned-outfielder—a former Yankee himself—never exceeded his 1952 total of 92 games played in eight big-league seasons. A lifetime .255 hitter, Souchock averaged .249 in 1952, including a personal-best 13 home runs and 45 runs batted in (his peak was 46 RBIs in 1953). However, he enjoyed two .302 seasons, first in 1946 with the Yankees and later in 1953 with the Tigers.

Friendly, helpful, and hard-working, Souchock, the ultimate teammate, was nothing if not versatile. In 1949 with the Chicago White Sox, he began playing the outfield. A solid-fielding first baseman before then, he also played all three outfield positions, first base (93 games), third base (15 games), and second base (once) before his big-league career ended in 1955. Aside from his clutch hitting, including 50 homers in the majors and another 115 in the minors, Souchock may be best remembered by Tigers fans as the flychaser who was replaced by Al Kaline in 1954. Instead, Souchock’s experiences illustrated that he was really an aging big leaguer.

Born on March 3, 1919, in Yatesboro, Pennsylvania, to Nicola and Anne Souchock, Steve, or Bud, grew up with two older brothers. Their father worked in the coal mines and their mother raised the family. In those days athletics offered talented young men the opportunity to move up in life, and Steve loved team sports.

A six-footer by the time he reached the ninth grade, he told me about his schoolboy athletic career in 1997: “I played everything in high school. I was the best football player, the best basketball player. I was a lousy basketball player, but I was the biggest guy in the school. So I was the best basketball player, but I wasn’t a good basketball player.”

Like most youths of the era, Steve also played baseball: “We played all the high-school teams in Armstrong County. I don’t know the exact details of it, but we played baseball. That’s why I was probably the best, because I was bigger and stronger than most of the kids at my age.”

In 1938, near the end of the Great Depression, the 19-year-old left high school. His father was ill, and Steve needed to work to help support the family. He moved to Dearborn, Michigan, found work on Ford’s assembly line, and played semipro football that fall with a local club. Unhappy in Michigan, he returned home in the spring.

“I had to get a job someplace,” Souchock recalled. “The only place I knew what to do was in Greensburg.” He went to Greensburg with his friend Chooky Pizcohich to try out for the minor-league baseball club there.

“I went down, and I was sick that day,” Souchock recalled. “I guess I had the flu. I get it all the time. Both of us were there on Monday, and we got released on Wednesday. But they told me to come back when I got well, because they didn’t have money for doctors, and so on. So I got well, and I went back the following Monday, and I made the ballclub.”

Souchock signed with the last-place Greensburg Senators of the six-team Class D Pennsylvania State Association for the monthly rate of $65. Playing 39 games as a first baseman, his natural position, he hit four home runs and drove in 26 runners. However, the club’s weak finances forced the owners to sell him to the Yankee organization in June 1939. Thinking about his first professional experience, Souchock recalled, “I didn’t know what the hell was going on. I was just a little country boy coming from nowhere, you know, and that’s the way it goes.”

Souchock was talented and strong, but he was also stoic and humble. After going home for a couple of days to visit his father and mother, he took the train to Easton, Maryland, to play for the Yankees’ club in the Class D Eastern Shore League. In 65 games, the big guy hit eight homers and drove in 36 runs, averaging .257 for the remainder of the 1939 season.

“I’ll tell you a story about that,” Souchock reminisced. “Joe DiMaggio was hot at that time, and they changed my stance at that time, because I guess I had a little bit of power. My power was in the wrong fields. It was in center field, right-center. I was in a slump, and I was a young kid away from home for the first time. I was having a bad time with the bat. I was working out, and I couldn’t hit in batting practice when we worked out in the morning.

“I says, ‘The hell with it. If I can’t play in this league, I better find something where I can make a living.’ So I quit in the morning. I went in and took a shower, packed my bag, and the manager, Ray Powell, was sitting there in the grandstand, waiting for me.

“He says, ‘Steve, what are you going to do when you get home?’

“I says, ‘Hell, I don’t know.’

“He says, ‘Well, listen. Why don’t you hang around and finish out the season? We’re not gonna win the pennant, and you can make up your mind in the fall.’

“In the meantime, I had cooled off a little bit. I says, ‘Well, tell you what I’ll do. I’ll play another week. If I don’t do any better in the next week than the way I’ve been going, then I have to find another job in my lifetime.’

“And I got two base hits that night, not good hits, but ‘wounded quails.’ I felt like I hit two home runs! That’s how good I felt. I hadn’t gotten a hit in I don’t know how long. Then I just went crazy from that day on. My batting went up, I don’t know what it went up to. But I got confidence in myself. But if it wasn’t for Ray Powell, I probably wouldn’t be sitting here right now talking to you.”

Souchock went home and worked during the offseason. In 1940 the Yankees sent him to Akron of the Class C Middle Atlantic League, and the club topped the six-team loop. “I hit 24 or 25 home runs [he hit 24], and my eyes went bad. I was leading the league in everything, home runs, runs batted in. I had trouble seeing, the bright sun bothered me. I went to the manager, Pip Kohler, and told him I was having trouble with my eyes.”

The club sent Souchock to a doctor, who recommended that he see a specialist at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. But he wanted to help the ballclub, so he decided to wait. “I finished out the season. I think I hit .310. But my average was falling down. I went from maybe .340, .350, .360, whatever I was hitting, down to .310. I remember the .310. I don’t remember the rest. I went to Johns Hopkins Hospital when the season ended, and I was there for a week for my eyes.”

Souchock learned he had “photophobia,” which meant that too much sun was getting behind his eyes. He was given medicine to take in the offseason. He couldn’t be around bright lights or even attend the movies. But his eyes got better by 1941, and he never returned to Johns Hopkins.

Improving steadily, Souchock enjoyed two productive seasons. In 1941 he played briefly with Binghamton of the Class A Eastern League, hitting .375 in four games. But the club had another first baseman, so Souchock was sent to Norfolk of the Class B Piedmont League, where he played 125 games and batted .272, contributing eight home runs and 69 RBIs.

In 1942 Souchock enjoyed a career year. After eight games at Kansas City of the Double-A American Association, a Yankees’ personnel shuffle sent him back to Binghamton of the Eastern League. Topping the circuit with a .315 average, Souchock also led in runs scored, with 94; in doubles, with 29; in triples, with 15; and in RBIs, with 91. Big Steve slugged 13 homers, ranking second to Albany’s Ralph Kiner, who hit 14 home runs en route to a Baseball Hall of Fame career with the Pittsburgh Pirates. Souchock, however, was voted the Eastern League’s MVP. (In September 1996 he returned to Binghamton and was inducted into the team’s Hall of Fame.)

World War II interrupted the peacetime pursuits of most Americans as well as most major and minor leaguers, and Souchock was no exception. He enlisted in the Army after the 1942 season, and he took basic training at Camp Lexington in Louisiana in 1943. He played several games for the camp’s baseball team before being sent to France in mid-1944. Assigned to the 691st Tank Destroyer Battalion of the 87th Infantry Division, Souchock and his unit saw action for 16 months in France, Luxembourg, Belgium, and Germany in 1944 and 1945. Big Steve commanded a gun crew, and he was decorated several times for bravery, once receiving the Silver Star. His outfit fought in the Battle of the Bulge, and he received the Bronze Star for valor there. On December 6, 1945, he was mustered out of the Army at Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania.

Souchock, like other athletes in the US armed forces, returned to his sport, professional baseball, in the spring of 1946. The major leagues expanded to 30-man rosters for the first postwar season to accommodate the ballplayers who had served their country during the war, and the Yankees had Souchock on their roster.

Other changes were in the works for baseball, including a challenge from millionaire Jorge Pasquel, who signed a handful of big leaguers and brought them south of the border to play in the Mexican League. Jackie Robinson produced a stellar season for Montreal of the Triple-A International League that foreshadowed Robinson’s breaking of the majors’ color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. The gradual rise of television in American life was a technological change that led to greater access to pro sports by fans. In fact, major-league attendance peaked during the 1948 season at nearly 21 million, a number that would not be surpassed until the expansion season of 1961.

“I didn’t belong in the big leagues in ‘46,” Souchock explained to me. “I knew that. But rules were that they had to keep 30 players. I asked to go to the minor leagues to see if I could play, because I missed three years. Because of the rules, they put me on waivers, and nobody claimed me. So I says, ‘How the hell can anybody draft me? With my name, nobody even remembers me.’ I stayed with New York on the bench and played a little bit.”

The Yankees, finishing in third place and going through three managers, spent much of the season looking for another Lou Gehrig at first base, but to no avail. Left-handed-hitting Nick Etten held down the position for the Yankees in 1943, 1944, and 1945, and he batted .271, .293, and .285, respectively. A star during the war years, leading the American League with 22 homers in 1944, the mediocre-fielding Etten averaged .232 against the returning big-league hurlers. The club also tried right-handed-batting outfielder Johnny Lindell at the position, but the 6-foot-4½-inch Lindell, who hit .259 with 10 home runs and 40 RBIs, failed as a first sacker.

On July 15 Bill Dickey, the second of three New York managers in 1946, benched Etten and began using Souchock, then hitting .111, at first base. Adjusting slowly, the 27-year-old rookie was jittery and awkward for a few games. However, the “husky utility player” soon proved capable in the field. Souchock enjoyed his highlights, notably a four-hit game—two singles, a triple, and a two-run homer—as part of a 16-hit assault to sink the White Sox, 10-4, at Comiskey Park on July 28. He finished the season hitting a surprising .302, contributing three doubles, two triples, two home runs, and 10 RBIs in 86 at-bats spread over 47 games.

Still, as was the case with other players who began their careers in the late 1930s or the early 1940s, World War II slowed Souchock’s development. He needed to play on a regular basis, partly to improve his skills and partly to boost his confidence. The Yankees’ management knew it, and as a result, they optioned him to Triple-A Kansas City for the 1947 season. Facing American Association pitching for the entire summer, Souchock came through in good fashion, averaging .294 and producing 25 doubles, 11 triples, 17 home runs, and 99 RBIs.

Calling his 1947 season a “good year,” Souchock recollected, “I went back the next year with the Yankees. I think I have the ballclub made. I’m having a hell of a year in 1948. I’m feeling good, and I’m hitting good. And I got hit on the wrist with a ball, playing against the Tigers. Art Houtteman hit me, and I broke my wrist. So my season was over, you know, in spring training.”

The injury, suffered at the Yankees’ ballpark in St. Petersburg on March 12, hurt Souchock’s chances with the Yankees in 1948. After capturing the AL pennant in 1947 and outlasting the Dodgers in an exciting seven-game World Series, the Yankees slipped to third place in 1948 behind the pennant-winning Cleveland Indians and the runner-up Boston Red Sox. Veteran George McQuinn, a 5-foot-11 left-handed batter acquired in a trade with the Philadelphia Athletics, played first for the Yankees in 1947, hitting .304 with 13 home runs and 80 RBIs. In 1948 McQuinn played the finale of his 12 big-league seasons, but he slipped to .248, with 11 homers and 41 RBIs. Souchock came off the bench and sometimes played the second game of doubleheaders, getting into 44 games but hitting only .203 with three homers and 11 RBIs.

Steve’s career illustrates how important the factors of good timing and avoiding injuries can be to any ballplayer: “I was really going good in 1948, and George McQuinn was holding out. He had a pretty good year in 1947. But it looked like I had the ballclub made, if I kept doing what I was doing, until I got hurt. When I got hurt, I didn’t have any spring training. Everybody was out in front of me, and I didn’t get much playing time. Then I got traded to Chicago. I’m not complaining about anything. That’s the way life is. But I had a tough break there.”

On December 14, 1948, the Yankees traded Souchock to the Chicago White Sox for Jim Delsing, a solid left-handed hitter and a fine outfielder. The speedy Delsing could give occasional relief in center field to superstar Joe DiMaggio, who was 34 in 1949. With the White Sox, Souchock again saw limited playing time. His circumstances were complicated when new pilot Jack Onslow brought up several of his players from Memphis of the Southern Association, where he had managed in 1948.

Still, Souchock, who got into 84 games, 39 in the outfield and 30 at first base, led the sixth-place White Sox in home runs with seven, and he contributed 37 RBIs. While he batted a career-low .234, he gained valuable experience in the outer gardens. Mostly Steve played left field when Gus Zernial, a Chisox rookie, was hurt. Zernial batted .318 with five home runs and 38 RBIs, but the White Sox’ runner-up in the power department was second baseman Cass Michaels, who hit .308 with six homers and a team-high 83 RBIs.

Souchock recalled, “Comiskey Park was a tough place to play. When the wind was blowing in, you had to change your style of hitting, because if you hit the ball good, the wind was going to hold it up. You know, in different parks, you have to compromise. When the wind blows out in Chicago, if you hit the ball in the air, it travels out. But generally, it blows in, and it’s a tough place to hit home runs.”

In any event, Chicago wanted younger players, and Souchock was 30 in 1949. On December 8, the White Sox sold him to the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League. Steve enjoyed a banner season for Sacramento in 1950.

“I had a pretty good year out there,” Souchock said. “I drove in 99 runs and hit 30 home runs,” which set a new Solons record; he also hit .291. “I hit three home runs one day, which I have to brag about a little bit. It’s tough to hit three home runs! I enjoyed it out there. It was probably the best league in baseball to play. When you were playing in the Coast League, you came into a town and you were there for one week, and you had Mondays off. You didn’t have to pack a suitcase every third day to get on a plane or bus, or whatever.

“When you went to Seattle, you had Monday off, you played Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and a double-header Sunday. You had Monday off, you went to Portland, you played Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, had a double-header on Sunday. Then you came home and you had Monday off. It was a hell of a league.”

More importantly, Souchock’s performance that season led to a major opportunity. Detroit drafted him after the 1950 season. He had built a home in Dearborn, west of Detroit, after he came home from the service. Nemo Leibold, who had seen Souchock play in the Eastern League and also the PCL, told the Tigers about him. When Leibold came by to visit Souchock and inquired about his back (he injured it hitting a wall at Sacramento), Steve knew Detroit would draft him. Saying, “I feel fine,” he signed with the Tigers.

Detroit general manager Billy Evans was looking for a right-handed-batting pinch-hitter and an outfielder. As it developed, Souchock, 6-feet-2 and now a 200-pounder, filled both jobs in excellent fashion. In 1951 he averaged .245 with 11 homers and 28 RBIs in 91 games. Of equal importance, he handled almost every position except pitcher and catcher. Indeed, Souchock, who was a smart baseball man with a positive can-do attitude and a good sense of humor, came into his own with Detroit. He more than filled the need for a versatile fielder and a stellar hitter.

“That’s when I became a little bit of everything,” he said. “I became a utilityman and played all the positions. I played outfield, all fields, left field. I played one game in center field against the Yankees. I played right field, first base, third base, and filled in for a few innings at second base. I was a decent ballplayer with Detroit.” Always modest, he added, “I wasn’t good with Chicago or New York.”

In 1951 Detroit had a roster full of veteran players, but not enough of them enjoyed good seasons. The Tigers had finished second in 1950 with a 95-59 record, three games behind the Yankees, thanks largely to a pitching staff featuring five starters who won 10 or more games, paced by Art Houtteman’s 19-12 record, Fred Hutchinson’s 17-8 mark, and veteran southpaw Hal Newhouser’s 15-13 ledger.

But Detroit fell to fifth place in 1951, compiling a 73-81 record, as Houtteman went into the service during the Korean War, Newhouser spent much of the season on the disabled list with a sore arm (Hal was 6-6), and outfielder Hoot Evers, who had averaged .323 in 1950, slumped, hitting just .224. In 1950 five Tigers batted .300 or better, led by George Kell’s .340 average. But in 1951 Kell’s .319 was the only Tiger mark above .300.

Detroit’s regular outfielders featured the right-handed batting Johnny Groth in center, left-handed slugger Vic Wertz in right field, and Evers, a right-handed batter, in left. Wertz batted .285 and led the Tigers with 27 four-baggers and 94 RBIs. Groth, who had more speed than power, averaged .299 with three homers and 49 RBIs. Evers, who struggled at the plate, still hit 11 home runs and produced 46 RBIs. Pat Mullin, a left-handed batter who had been a Tiger since 1940 (he missed four wartime seasons), played 110 games, hitting .281 with 12 homers and 51 RBIs.

Souchock fit nicely into the mix, because he could play anywhere. Batting .245, he was particularly effective against left-handed hurlers. Playing in 91 games (59 in the outfield), he contributed 10 doubles, three triples, and 11 home runs among his 46 hits, and he added 28 RBIs.

In 1952 Detroit dropped to eighth (last) place. Losing 10 of the first 13 games, the Tigers fell to the AL cellar by May 2. The team tried to improve via the trade route, notably in a nine-player swap with the Red Sox. Detroit received Walt Dropo, the big first baseman, third sacker Fred Hatfield, shortstop Johnny Pesky, outfielder Don Lenhardt, and pitcher Bill Wight. In return, Boston obtained third baseman George Kell, later a Hall of Famer, Hoot Evers, shortstop Johnny Lipon, and veteran right-hander Dizzy Trout.

Despite the trade, Detroit’s the losing continued. On July 5 the Tigers fired manager Red Rolfe and replaced him with the savvy Fred Hutchinson, one of the club’s best pitchers. The Tigers continued to struggle, and Virgil Trucks’ roller-coaster season—during which two of his five victories were no-hitters—illustrated Detroit’s plight. Souchock made a valuable contribution, playing in 92 games and hitting .249 while producing 45 RBIs. Again he added timely power, belting 16 doubles, four triples, and 13 home runs. He also played 13 games at third base and nine more at first base, in addition to his 56 contests as a flychaser.

The next year the Tigers improved, climbing to sixth place with a 60-94 ledger under Hutchinson’s leadership and a youth movement. In 1953 the team signed three “bonus” rookies, notably 18-year-old Al Kaline, who came out of high school in Baltimore to the big leagues and, finally, to a 22-year Hall of Fame career. Further, shortstop Harvey Kuenn, 23, who signed off the campus of the University of Wisconsin in September 1952, led the team with a .308 average, paced the league with 209 hits, and was named AL Rookie of the Year.

The most important of several trades occurred with Cleveland on June 15, when Detroit received infielder Ray Boone and three pitchers, Steve Gromek, Al Aber, and Dick Weik, in return for hurlers Houtteman and Wight, catcher Joe Ginsberg, and infielder Owen Friend. Boone was the big gun in the deal, and he solidified third base for Detroit. More comfortable with the “hot corner” than he had been at shortstop for Cleveland, Boone batted .296 with 26 home runs and 114 RBIs. At the same time Souchock enjoyed his best season. Younger athletes played ahead of him, Don Lund in right and Bob Nieman in left field, but Steve encouraged them. Back problems held him to 80 games in the outfield (he played once at first), but he batted .302 for the second time in his career. In 278 at-bats, his major-league high, he slugged 13 doubles, three triples, and 11 home runs while delivering a personal-best 46 RBIs.

Steve enjoyed telling stories, including about unusual four-baggers. For example, rain washed out a game with Philadelphia in Detroit on June 21, 1952. The A’s were leading the Tigers, 4-2, in the bottom of the fourth when the contest was called. Souchock bemoaned (jokingly) the rain, because he lost a two-run homer that provided his club with its scoring up to that point. Further, he lost two circuit clouts to rained-out games in 1951, and one of those was a grand slam that he blasted against the Yankees.

Later that summer, Souchock won back-to-back games for Detroit against New York with home runs. At Briggs Stadium on July 25, the big guy sent a large crowd of 41,538 happily on their way when he hit Bob Kuzava’s first pitch in the bottom of the ninth for a solo shot to beat the Yankees, 3-2. Eighteen hours later, pinch-hitting for pitcher Ted Gray in the last of the 11th, he beat New York again, slugging one of reliever Bobby Hogue’s slants for a grand slam that lifted Detroit to a 10-6 victory.

Later that summer, Souchock won back-to-back games for Detroit against New York with home runs. At Briggs Stadium on July 25, the big guy sent a large crowd of 41,538 happily on their way when he hit Bob Kuzava’s first pitch in the bottom of the ninth for a solo shot to beat the Yankees, 3-2. Eighteen hours later, pinch-hitting for pitcher Ted Gray in the last of the 11th, he beat New York again, slugging one of reliever Bobby Hogue’s slants for a grand slam that lifted Detroit to a 10-6 victory.

Hope springs eternal in the diamond sport, and Souchock played winter ball in Cuba in early 1954, hoping to be better prepared for another good season. Unfortunately, he broke his wrist and had to wear a cast until mid-June. The Tigers placed him on the DL, and the 35-year-old finally returned to the active roster on June 15. Detroit was improving, and the Bengals finished in fifth place with a 68-86 mark. Souchock showed his old form on July 28, cracking a pair of three-run homers to help Al Aber pitch a complete-game 10-2 victory over the Athletics.

By that time Kaline was entrenched in right field. The talented 19-year-old adjusted to life in the majors by playing 138 games, making several sensational catches, racking up 16 assists, and batting .276 with four homers and 43 RBIs. Kaline said later that his glove kept him in the lineup in 1954, but observers knew he was destined for greatness.

Souchock admired Kaline, stating the Baltimore native played right field in Detroit better than anyone he ever saw. Steve recalled, “When the ball was hit down the right-field line in Detroit, in that corner, it was a double, a two-base hit, regardless of who was playing right field, whether it was Vic Wertz, whether it was Pat Mullin, or whether it was Souchock. Generally, it was a two-base hit. When Kaline came, it wasn’t a two-base hit. There were a few guys that did it, but they had to slide into second base.”

Steve observed, “I would pay my money to see Kaline play. That’s how great I think he was.”

Asked if he minded losing his job to Kaline, Souchock laughed and said, “No. Hell, I use that all the time when I make a talk someplace. I say, ‘Al Kaline took my job. But he would have taken my job whether I broke my wrist or not!’”

Commenting on Souchock, former Tiger Jim Delsing once observed, “I remember Steve as a great hitter, especially against left-handed pitching. He was also great for the team, always encouraging his teammates and helping people with their problems with hitting and fielding. To sum up everything, Steve was a great team player, friend, and teammate, and he always had good stories to tell.”

Souchock played in only 25 games in 1954, hitting a career-low .179. The veteran was 7-for-39, but his seven hits included one double and three home runs, and he drove home eight runners. In 1955 Steve collected his final major-league hit, an eighth-inning pinch single off rookie Cleveland left-hander Herb Score to drive home Detroit’s final run in a 7-3 loss at Briggs Stadium.

Three weeks later, on May 11, the Tigers sold Souchock to Buffalo, Detroit’s affiliate in the Triple-A International League. Just over a month later, after hitting .264 for the Bisons in 30 games, the self-described utilityman was hired by New York to manage Little Rock, the Yankees’ farm team in the Double-A Southern Association. The Travelers were mired in last place, and Souchock’s club finished 38½ games out of first. He returned in 1956 and piloted the combined Little Rock-Montgomery (Alabama) Rebels, but the club finished last again.

Nevertheless, the Yankees liked Souchock’s knowledge, skills, and personality, and the former New Yorker was sent to Binghamton of the Eastern League in 1957. There Souchock managed the Triplets to a first-place finish. In 1958, with fewer quality players, Souchock’s Binghamton club slipped to third. In 1959 and 1960, Souchock managed Richmond of the International League to fourth and third place finishes, respectively, before he tired of the grind of minor-league life and travel.

Souchock had purchased a house in the Detroit suburb of Dearborn when he first joined the Tigers, and he lived there for almost 40 years. After leaving baseball, he enjoyed taking care of his yard, playing golf, and reading.

Steve, a bachelor during his major league years, married Shirley Botkin, of Kansas City, in August 1956. She traveled, moved, and lived the baseball odyssey with her husband. The couple never had any children. Shirley passed away in 1988. At the time, the former Tiger was scouting for Detroit’s system.

Reflecting on World War II in 1997, Souchock said he seldom spoke about his wartime experiences in the European Theater. In fact, he was decorated twice for bravery, and he won the Bronze Star during the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944. The former big leaguer talked about one colonel, whom he remembered as Wild Bill (he didn’t recall his last name), because the officer saved Steve’s life during one battle. Those were critical days, the former big leaguer emphasized. Baseball wasn’t as important in 1943, 1944, and 1945. Instead, the survival of democracy was the name of the game.

Souchock loved baseball. He spent most of his adult life playing or working with the professional game, was one of those hundreds of thousands of rugged American soldiers who fought in the Second World War. Fortunately, he survived, returned home, and resumed playing the national pastime. Gaining valuable experience, he became a very good ballplayer.

When his major league days ended in 1955, Souchock managed in the minors and instructed rookies for the Yankees’ spring camp. The veteran also scouted for the Yankees from 1962 through 1974 and, after a time away from the game, he scouted for the Tigers from 1988 through 1996.

In effect, Steve Souchock was a man for all seasons, the kind of major leaguer that young boys used to love to read about in the newspapers, hear about when their favorite team’s games came on the radio, emulate on the dusty ball fields of yesteryear, and collect baseball cards to be preserved in shoeboxes or drawers.

I know, because I acquired Steve “Bud” Souchock’s cards from Bowman bubblegum packs in 1953 and 1954 during my schoolboy years in Flint, Michigan. For me, Souchock was a Tigers’ hero.

Last revised: October 5, 2017

Sources

The author published a shorter version of this article in Oldtyme Baseball News, Volume 8, Number 4 (1997), pp. 35-39: “In Search of Lost Heroes: Cot Deal, Bennie Huffman, Rudy Meoli, Steve Souchock”

Books

Baseball Encyclopedia 9th ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1993

Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball 2nd ed. Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America Inc., 1997

Official 1954 Baseball Register. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1954

Smith, Fred T., Tiger S.T.A.T.S: Statistics, Trivia, Alumni, Trades, and Stories. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Momentum Books Ltd., 1991

Articles

“Gordon, Etten Reported as Storm Center Within Ranks of Uneasy Yankees,” Washington Post (hereafter cited as WP), July 16, 1946

John Drebinger. “Souchock’s 4 Hits Pace 10-4 Victory,” New York Times (hereafter cited as NYT), July 28, 1946

“Bombers Prepare for 1948 Campaign,” NYT, October 11, 1947

John Drebinger, “Yanks Have Five-Man Battle for Position of First Baseman,” NYT, March 5, 1948

John Drebinger, “Reynolds, Bevens and Paige Win, 5-0,” NYT, March 13, 1948

—, “Unlucky Souchock Loses Another Homer in Rain,” NYT, June 22, 1952

—, “Homer By Tiger In Ninth Beats Yankees, 3-2,” Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1952

“Grand Slam by Souchock Beats Yanks,” WP, July 27, 1952

John Drebinger, “Trucks of Tigers Hurls No-Hitter, His Second of Season, Against Yankees, NYT, August 26, 1952

“Tigers Triumph, 10-2,” NYT, July 29, 1954

“Herb Score Wins for Indians, 7-3,” NYT, April 16, 1955

“Sain, Slaughter Go To Athletics,” NYT, May 12, 1955

“Souchock to Manage,” Hartford Courant (hereafter cited as HC) June 25, 1955

“Rebs’ Steve Souchock Marries in Nashville,” August 9, 1956, courtesy of HOF.

“Trade Rumors Dominate Minor League Meetings,” Christian Science Monitor, December 5, 1956

“Stengel To Open Yanks’ Prospect School, Feb. 14,” HC, January 7, 1957

“Baseball Winter League For Rookies Seen Success,” HC, December 16, 1958

“Yanks List 31 Training Games; Drop Spring School for Rookies,” NYT, January 7, 1959

“Sturdivant and Kucks Pitch Impressively in Yankee Squad Game,” NYT, March 5, 1959

“Yanks Crush Richmond, 10-2, In Wind-Up of Exhibition Tour,” NYT, April 9, 1959

“Highly Skilled coaching Staff Makes Task Easier for Berra,” NYT, February 26, 1964

“Yankees to Open Florida League With 23 Players,” Los Angeles Times, September 27, 1968

Online

Baseball Reference.com – http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/f/frailke01.shtml

Gary Bedingfield’s Baseball in Wartime – http://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/souchock_steve.htm

SABR: Souchock’s scouting information comes from the Scouts Committee’s Scouts Roster Database

Interview

This article is based in part on a telephone interview with Steve Souchock on January 16, 1997.

Other

Copy of Marriage License of Steve Souchock and Shirley Botkin, August 8, 1956, Sumner County, Tennessee, courtesy of National Baseball Hall of Fame (hereafter cited as HOF).

Picture of the headstone of Shirley Magee Souchock, dated 1919-1988, courtesy of Karen Bergeron.

Full Name

Stephen Souchock

Born

March 3, 1919 at Yatesboro, PA (USA)

Died

July 28, 2002 at Westland, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.