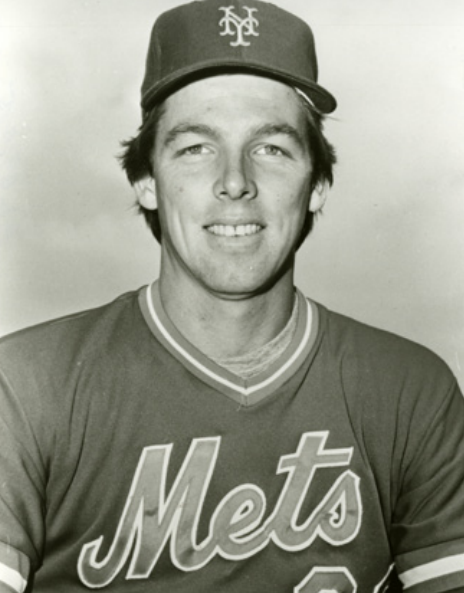

Ed Lynch

Never possessed of an overpowering fastball or a devastating curve, Ed Lynch relied instead on his command, and his wits. The latter, it was said, were among the sharpest of their time, and led to a second act as a baseball executive.

Never possessed of an overpowering fastball or a devastating curve, Ed Lynch relied instead on his command, and his wits. The latter, it was said, were among the sharpest of their time, and led to a second act as a baseball executive.

“I’m a competitive person and I have confidence in my abilities,” Lynch told the New York Times. “I wouldn’t have pitched seven years in the big leagues throwing 81 miles per hour if I couldn’t get the most out of my abilities.”1

The above remark—made as Lynch assumed the job of general manager of the Cubs in 1994—may have been an exaggeration but it was not a big one. And it was typical of the witty quips and one-liners that made for lively newspaper copy during Lynch’s big-league playing career, which spanned 1980 to 1987 for the New York Mets and Chicago Cubs. A small sampling of his way with words:

On the Mets’ pitching staff losing Tom Seaver to a surprise compensation draft pick by the Chicago White Sox: “The day he left the Mets it was like the president being assassinated. We all moved up a notch in our jobs but we’d rather it not happened.”2

On the wave of young talent that lifted the Mets into sudden contention in 1984: “They have no idea the Mets have been brutal for eight years. While we’ve been stinking up the league the Mets have built the best farm system in the majors. These kids are winners. They don’t care if we’re playing the Montreal Expos or the Bad News Bears.”3

On fan reaction to his pitching as compared to that afforded to his teammate, strikeout phenomenon Dwight Gooden: “What are they going to do for me? Put cards on the wall that say ‘4-3’?”4

When Mets teammate Ray Knight named his daughter Erin Shea: “It’s a good thing you didn’t play for the Giants.”5

Edward Francis Lynch was born on Feb. 25, 1956, in Brooklyn. He grew up in Westchester County, New York, and in Miami. He attended Christopher Columbus High School, a Catholic school in Miami where he was named All-City in basketball and baseball. It was the former sport in which he excelled. Lynch was not the best baseball player in the school, or even his family: That honor belonged to his brother Chris.

A year older than Ed, Chris Lynch, also a right-handed pitcher, impressed scouts enough to be drafted three times. The Cardinals selected him in the 13th round out of Christopher Columbus in 1972, but he elected to go to college at Miami-Dade instead. The Mets made him a third-round selection in the January 1973 draft, and the Dodgers picked him in the 20th round in 1974, but he didn’t sign, choosing instead to complete his college degree, then go on to law school.

Ed in the meantime rode his basketball skill to a scholarship at the University of South Carolina, only to wind up as a key member of the Gamecocks’ baseball squad. In 1977 South Carolina, under first-year coach June Raines, advanced to the finals of the College World Series, only to lose twice to champion Arizona State. Lynch started and lost the first of those games, a 6-2 complete-game decision.

Lynch, a 1977 business-management graduate, was one of four future major leaguers on that South Carolina squad. Ace starting pitcher Randy Martz was selected by the Cubs 12th overall in the 1977 June amateur draft and went on to a four-year big-league career with the Cubs and White Sox. Outfielder Mookie Wilson, a second-round draftee of the Mets that year, played in the big leagues for 12 years, while reliever Jim Lewis, signed as an undrafted free agent by Seattle, made appearances for the Mariners, Twins, and Yankees.

As for Lynch, he was selected by the Rangers in the 22nd round that year and assigned to their Gulf Coast League affiliate, where he went 1-4 with a 3.70 ERA. Lynch made rapid progress up the organizational ladder for Texas, getting an all-star bid with Asheville of the Class-A Western Carolinas League and a promotion to Double-A Tulsa during 1978. He won 10 games for the Triple-A Tucson Toros in 1979, including a complete-game, 6-1 victory over Spokane on August 8 notable for the fact that Lynch needed just 78 pitches to complete the effort.

Texas, on the outskirts of the AL West pennant race that summer, less than two weeks later traded with the reeling Mets for veteran first baseman-outfielder Willie Montañez. The deal called for the Mets to receive two players to be named: veteran utilityman Mike Jorgensen was one; Lynch was the other, assigned to the Mets after the end of Tucson’s season.

Lynch arrived in the Mets organization only months before new ownership and a new management team commenced a thorough and lengthy rebuilding. Lynch became a mainstay of the team as it rebuilt, enduring several grim seasons only to be traded months before it culminated in a 1986 World Series championship. As he succinctly put it, “It was like living with a family all year, then getting kicked out on Christmas Eve.”6

Lynch spent most of the 1980 season pitching for the Tidewater Tides, the Mets’ Triple-A team in Norfolk, Virginia, but was summoned to the big leagues in late August when Mets pitcher Craig Swan went down with shoulder trouble. Lynch made his major-league debut on August 31, 1980, in Candlestick Park, entering a game in which the Mets were trailing 6-4 in the seventh inning, and was hit hard—the first batter he faced, Mike Ivie, ripped a double to center field and by the time Lynch departed in the eighth he’d be charged with four runs in an inning and a third on four hits including a run-scoring triple by the opposing pitcher, Al Holland.

Lynch redeemed himself in his next appearance, a start at Shea Stadium on September 18, earning his first major-league win in a 4-2 victory over the Chicago Cubs. Lynch overall made five appearances in 1980 (four starts), with 1-1 record and a 5.14 ERA.

Lynch began the 1981 season with Tidewater but was summoned to New York in April, again after an injury to Swan, this time a broken rib suffered when he was struck by a ball thrown by catcher Ron Hodges, who was attempting to throw out Tim Raines stealing second. Lynch remained with the Mets until Swan returned in June, just two days before a strike interrupted the season. Lynch returned to the Mets in August, finishing the year with a 4-5 record and a respectable 2.91 ERA in 17 games including 13 starts.

The Mets fired manager Joe Torre after the 1981 season and replaced him with George Bamberger, best known as Earl Weaver’s trusted pitching coach with the Orioles teams of the 1960s and ’70s. Bamberger had a special admiration for the 26-year-old Lynch, who in his first full season at the big-league level provided reliable middle relief and 12 starts, finishing 4-8, 3.55 for a team that struggled through a 97-loss campaign.

“Eddie did everything you had to do to win,” recalled Marty Noble, a former beat writer for Newsday who covered that team. “He fielded his position properly. He always covered first base. He was one of the first guys I remember using the slide step, and he held runners very well. He could bunt and help himself. All those little things they talk about to help yourself, he did. And George Bamberger just loved him for that.”7

Although Lynch possessed the frame of a power pitcher (6-feet-6, 230 pounds), he was anything but. Lynch’s fastball rarely traveled faster than 84 miles per hour, but it had good sink, and he commanded it well, backing that up with a slider and changeup. He pitched to contact, striking out just 396 batters in 940⅓ innings pitched in his big-league career, and walking even fewer (229).

Batters combined to hit .284 off Lynch during his career, but some felt they could do better. Some opposing players referred to Lynch as “Ed Lunch,” feeling they could “fatten up” on his pitching,8 but Lynch could also be a frustrating opponent, as revealed in a nationally televised game from Dodger Stadium in September of 1985.

In that contest, hard-swinging Dodgers Mariano Duncan and Pedro Guerrero, each evidently fed up with Lynch’s slow-and-slower repertoire, told him as much. “I told him he didn’t have (bleep),” Guerrero told the Los Angeles Times. “I told him to stop throwing all that junk.”9 When Lynch struck out Duncan with a fastball in the sixth and punctuated it with a “take that,” Duncan instead of returning to the home dugout at Lynch’s invitation raced toward the pitcher’s mound, only to be intercepted by Mets enforcer Ray Knight.

“It’s no secret,” Keith Hernandez wrote in his book on the 1985 season, If at First…. “Eddie is sensitive to the charge that for being such a big guy, he doesn’t throw very hard. He would have fought Duncan gladly, if Knight hadn’t intervened.”10

The addition of veteran starters Tom Seaver and Mike Torrez to the 1983 Mets squad initially cost Lynch starting assignments, but he joined the regular rotation in May when back-end starters Scott Holman and Rick Ownbey faltered. Lynch won 10 and lost 10 in 30 games (27 starts) that year, while his earned-run average ticked up to 4.28. Under managers Bamberger (who resigned in May) and Frank Howard, the 1983 Mets finished in the National League East basement for the second straight year, although the midseason addition of All-Star Keith Hernandez and the promotion of rookies including Darryl Strawberry and Ron Darling during that year signaled the turnaround effort that would begin to bear fruit.

Under new manager Davey Johnson, who brought along sensational rookie Dwight Gooden, the Mets made a sudden surge into contention in 1984. Lynch, who became the senior member of the pitching staff when Mike Torrez was released in June, got off to a 7-1 start as the Mets mounted a surprise challenge to division-leading Chicago. Lynch served a “swingman” role for the team, making 40 appearances overall, including 13 starts.

“He’s the most consistent pitcher on the staff,” Johnson said of Lynch in June. “I know no matter what way I use him he’ll get the job done.”11

Lynch became a focal point of the burgeoning Mets-Cubs rivalry during an August 7 doubleheader at Wrigley Field, when after a five-run Chicago outburst in the fourth inning, he hit Cubs slugger Keith Moreland in the back with a pitch, inciting Moreland to charge the mound and take down Lynch with a flying body block. The Cubs got the better of the scrum, and the National League race, taking both games of the twin bill and all four games in the series as they pulled away en route to a division title. The Mets finished with 90 wins, 6½ games behind Chicago, and a fatigued Lynch faltered down the stretch, finishing with a 9-8 record and a 4.50 ERA.

Lynch found himself back in the Mets’ starting rotation in 1985 and turned in what was probably his best overall year, going 10-8 with a 3.44 ERA and setting career highs in innings pitched, complete games, games started, and strikeouts. His walks-per-nine-innings rate of 1.272 ranked third in the National League that year and his WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) of 1.126 was 10th. The Mets finished 98-64 that season, fighting the St. Louis Cardinals until the season’s final week, but falling just short of a division title.

Lynch by then had become familiar to New Yorkers for his humorous quotes, often highlighting the lighter side of baseball. Noting Lynch’s mastery of clubhouse slang, Noble of Newsday asked the pitcher to put together a “story” using such phrases. Decades before social media, it “went viral.” Baseball fans can buy toilet paper printed with the following quote today, Noble noted.

“The bases were drunk, and I painted the black with my best yakker. But blue squeezed me, and I went full. I came back with my heater, but the stick flares one the other way and chalk flies for two bases. Three earnies! Next thing I know, skipper hooks me and I’m sipping suds with the clubby.”12

Slowed by nagging injuries in spring training, Lynch made only one appearance for the 1986 Mets before going on the disabled list with a balky knee that eventually required surgery. When he regained his health, the steamrolling Mets—fortified over the offseason with the addition of Bob Ojeda—packaged Lynch in a deal with the Cubs, receiving two prospects, pitcher Dave Lenderman and catcher Dave Liddell. Liddell eventually made it to the Mets in 1990 and singled in his first—and as it turned out, his only —major-league at-bat.

There was some press speculation that Lynch’s departure was precipitated by an arbitration win over the offseason that provided him a $530,000 salary for 1986, a bump of $200,000 or 60.6 percent from 1985, while the Mets had proposed $400,000. When asked if he felt his salary was a factor, the normally loquacious pitcher responded with just two words: “No comment.”13

In any case, Lynch was crestfallen upon being traded to the Cubs, who would struggle to 90 losses while his former club was on its way to winning 108 games and a World Series. But he pitched adequately in a familiar swingman role in Chicago, going 7-5 with a 3.79 ERA. And the Mets made sure he wasn’t forgotten: While four members of the 1986 squad who made small contributions to that team—Terry Leach, Randy Myers, Tim Corcoran, and John Mitchell—were not awarded World Series rings, Mets general manager Frank Cashen made certain that Lynch received one.

A second season with the Cubs in 1987 was not as successful, as Lynch dropped to 2-9, with a 5.38 earned-run average in 58 appearances for a last-place team.

The 1987 season was the 31-year-old Lynch’s last in the big leagues. Although invited to camp by the Red Sox in 1988, he was cut shortly before the season began.

Putting his playing career behind him, Lynch, like his brother Chris, enrolled at the University of Miami in pursuit of a law degree. Shortly after obtaining it in 1990, he was hired as director of player development for the Padres by Joe McIlvaine, who then was San Diego’s general manager. McIlvaine and Lynch had first crossed paths in the Mets organization, where McIlvaine worked in the front office during much of Lynch’s tenure.

McIlvaine returned to New York to succeed Al Harazin as Mets GM in 1993, and shortly thereafter named Lynch his special assistant. The combination of McIlvaine’s tutelage, and Lynch’s personal charm, in October of 1994 earned Lynch an offer from new Cubs CEO Andy MacPhail to become general manager of the Cubs. At 38, he was then the game’s youngest GM.

“I was looking for a general manager who was young, bright, and enthusiastic, and Ed possesses all of those attributes, and has the added dimension of having pitched in the major leagues,” MacPhail said upon appointing Lynch to succeed Larry Himes.14

Lynch proposed founding a team behind speed, defense, and pitching, with mixed results. Inheriting a team that finished last in the National League Central in 1994, the Cubs improved to a winning record (73-71) and a third-place finish in 1995, and fell to fourth place (76-86) in 1996 and fifth place (68-94) in 1997, before a 90-win season in 1998 secured the team’s first postseason berth in nine years. (The Cubs advanced to the Division Series by defeating San Francisco in a one-game playoff, then were swept by Atlanta in three games in the NLDS.)

The 1998 club, fueled by Sammy Sosa’s phenomenal 66-home run season, included a number of veteran contributors acquired by Lynch in trades and through free agency, including Lance Johnson, Mark Clark, and Manny Alexander (all acquired in a 1997 trade with the Mets), Mickey Morandini, Henry Rodriguez, and Kevin Tapani. These players bolstered an inherited base of Sosa, Mark Grace, and Steve Trachsel, along with Lynch’s first draft pick, fireballer Kerry Wood, who was on his way to winning Rookie of the Year honors. The club was managed by Jim Riggleman, whom Lynch selected to succeed Tom Trebelhorn shortly after taking the reins.

Lynch had a special admiration for Wood, notably speaking out when the freshly drafted high schooler threw 177 pitches during a school playoff tournament. “It’s just unbelievable that a so-called coach would jeopardize this kid’s future,” Lynch said. “This kind of behavior is borderline negligence.”15 Critics point out that Lynch, however, was at times too careless with other Cubs prospects. He traded 1997’s top draft pick, Jon Garland, then a minor leaguer, to the White Sox for ineffective reliever Matt Karchner. Garland went on to have a 13-year big-league career. Kyle Lohse was a throw-in when Lynch traded for his former Mets teammate, Rick Aguilera, in 1999: Lohse’s big-league career was still going 15 years later.

While much of the same cast returned for the 1999 season, the Cubs nosedived in June, and the 95-loss, last-place finish cost Riggleman his job. When new manager Don Baylor and a host of newly acquired players—Eric Young, Damon Buford, Ismael Valdez, and Joe Girardi among them—got the Cubs off to a slow start in 2000, Lynch offered to resign, but MacPhail elected to give the team more time to coalesce. But things only got worse amid weeks of speculation over a potential trade of Sammy Sosa, and MacPhail accepted Lynch’s resignation in late July.

Lynch, succeeded by MacPhail on an interim basis, remained in the Cubs organization for another decade as a special assistant to the GM before joining the Toronto Blue Jays as a professional scout in 2010. Lynch married the former Kristin Ann Kacer in 1986 and raised two children in Scottsdale, Arizona. Their son James, an outfielder, was drafted by the Blue Jays out of Pima (Arizona) Community College in 2014.

Sources:

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following:

Ultimatemets.com.

Baseball-reference.com.

scouts.baseballhall.org.

Notes

1 Jennifer Frey. “Lynch ‘Flattered’ to Become Cubs’ GM,” New York Times, October 11, 1994. Lynch actually pitched eight seasons in the major leagues.

2 Joe Goddard, “White Sox ‘84 Rotation: The Best Ever?” The Sporting News, April 2, 1984.

3 Joe Gergen, “Darryl Strawberry,” The Sporting News, May 21, 1984.

4 Author interview with Marty Noble, September 23, 2015.

5 Noble interview.

6 Frey.

7 Noble interview.

8 Noble interview.

9 Gordon Edes, “Dodgers Fight Off Mets for 7-6 Win: Duncan Starts Melee in 6th,” Los Angeles Times, September 8, 1985.

10 Keith Hernandez and Mike Bryan, If At First… (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1986).

11 Jack Lang, “Dependable Lynch a Steal for Mets,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1984.

12 Noble interview.

13 Malcolm Moran, “View from Top Elusive for Lynch,” New York Times, July 24, 1986.

14 Joseph A. Reaves, “MacPhail Names Lynch Cubs’ GM,” Chicago Tribune, October 11, 1994.

15 Dwain Price, “Cubs upset with coach after overthrowing top pick,” Fort Worth Star Telegram, June 8, 1995.

Full Name

Edward Francis Lynch

Born

February 25, 1956 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.