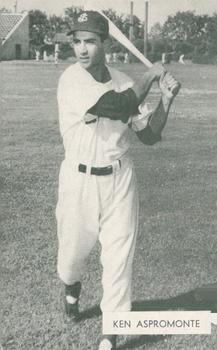

Ken Aspromonte

Brothers Bob and Ken Aspromonte were both graduates of Brooklyn’s Lafayette High School and both became major-league ballplayers. Ken was the eldest of the two, by nearly seven years, but Bob made the majors first, breaking in with the Brooklyn Dodgers (for all of one at-bat) in 1956. He didn’t return to the big leagues until 1960. Ken broke in with the Boston Red Sox in 1957 but he’d started his career years earlier, after signing with the Sox in 1950. Both played the bulk of the time as infielders.

Brothers Bob and Ken Aspromonte were both graduates of Brooklyn’s Lafayette High School and both became major-league ballplayers. Ken was the eldest of the two, by nearly seven years, but Bob made the majors first, breaking in with the Brooklyn Dodgers (for all of one at-bat) in 1956. He didn’t return to the big leagues until 1960. Ken broke in with the Boston Red Sox in 1957 but he’d started his career years earlier, after signing with the Sox in 1950. Both played the bulk of the time as infielders.

Bob Aspromonte had the longer playing career, but Ken supplemented his playing career with three years as manager of the Cleveland Indians, from 1972 through 1974.

The two faced each other only a few times, in 1962 and 1963. Bob spent his time exclusively in the National League, while Ken was an American Leaguer except for the second half of 1962 and the 1963 season, when he was with the Braves and Cubs respectively.

The first time they faced each other in a game was on August 2, 1962. The two teams had played the day before. Bob had played, but Ken had not. On the 2nd, they both played — and Bob won the game for the Colt .45s. He singled in the first inning, driving in two runs. Houston won the game, 3-0. Ken was 0-for-3. They were both in the same game again on August 10 (Ken was 0-for-2 and Bob was 2-for-5) and August 12, when Bob went 3-for-4 with an RBI, while Ken pinch-hit and was 0-for-1.

In 1963, after Ken had been traded to the Cubs, the two teams played each other 18 times, each team winning nine games. As for the brothers, they played each other on May 24 (Ken was 0-for-1 while pinch-hitting and Bob was 3-for-6 with an RBI.) On June 11, Bob rubbed things in a lot more; Ken walked as a pinch-hitter but Bob was 2-for-4 and won the game with a grand slam in the bottom of the 10th. Cubs manager Bob Kennedy never put Ken up against his brother again. After June 21, he never used him again. That was his last game in the majors.

In all, then, Ken had gone 0-for-7 with a walk in face-to-face games while Bob was 11-for-23 with nine runs batted in.

There was also a third brother who was briefly in baseball, the oldest of the three — Charles, who played in 1950 only, an outfielder for the Class-B Sunbury A’s (Interstate League) and the Class-B Kingston Colonials (Colonial League). He hit for a combined .230 batting average.

The elder sibling, Ken, was born in Brooklyn on September 22, 1931. He attended P.S. 248 in Brooklyn and then Lafayette High, with one year at St. John’s University. His parents were Laura and Angelo Aspromonte. Angelo (or Charles) worked as a bricklayer for 50 years, and had himself played sandlot baseball.1

“I grew up in Brooklyn,” he wrote over a bylined article in 1959. “I wanted to be a baseball player, but I didn’t want to be a Dodger. The other kids all wanted to be Dodgers. Not me. I wanted to be a Yankee. That meant life wasn’t dull for me. The other kids jockeying me all the time. These used to be some wonderful arguments at home. My father was a Dodger fan. An elder brother was a Dodger fan and signed with them. My father would explode, ‘Why can’t you be a sensible kid? Why do you hate the Dodgers? Why must you like the Yankees? The next thing, maybe, you’ll be rooting for the Giants, too?’ I’d grin and say, ‘Pop, the Dodgers don’t have Joe DiMaggio, He’s my boy.’”2 Ken added that one day while watching the Red Sox play the Yankees, he became entranced with Boston’s Bobby Doerr, in particular his drive and the impossible plays he made. “From that time I was a Doerr fan and imitator. I switched to second base and made him my model. He is still my idol. I hope I can come just close to being the guy he is on and off the field.”3

Ken was signed by the Boston Red Sox in 1950 by scout Frank “Bots” Nekola and Farm Director Johnny Murphy. He got in a lot of play that first season, first for the Oneonta Red Sox in the Class-C Canadian-American League (in 18 games, he hit .213) and then in Class D, where he played in 110 games for the Kinston (North Carolina) Eagles in the Coastal Plain League. He hit .295 and was named shortstop on the league all-star team.

He played for three teams in 1951 — Kinston, then another Class-C team for most of the year (the California League’s San Jose Red Sox), where he hit .299 in 93 games, and for Class-A Scranton (.216 in 31 games).

It was another three-team season in 1952, beginning in Triple A with Louisville, but again seeming to need more time to advance to a higher level. (He hit .241 in 12 games.) Then it was to the Roanoke Ro-Sox in Class B, where he hit .383 in 16 games. He settled in between with the Birmingham Barons (Southern Association, in Double-A ball), playing in 53 games and batting .247.

In 1953, Aspromonte spent the full season with the Louisville Colonels in the Triple-A American Association, hitting .243 in 96 games. At the end of the season, he was added to Boston’s roster. But Uncle Sam had other plans for him and he served in the US Army (Signal Corps) from December 1953 to October 1955.

Ken joined the Red Sox in Sarasota for early spring training in 1956, and was placed on the roster of their San Francisco Seals affiliate. Red Sox manager Mike Higgins was said to regard him as “the most versatile of his rookies, a second Billy Goodman.”4 Aspromonte was placed with the Seals and had a good year in the high-caliber Pacific Coast League. In 141 games, he hit .281 with three home runs, mostly playing second base but getting in several games at shortstop. In July, the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Ken’s younger brother Bob to a nonbonus major-league contract.

Ken had earned praise from former Red Sox second baseman Bobby Doerr, but his season was cut short by an emergency appendectomy at St. Luke’s in San Francisco on August 29. He was cheered in late September by an invitation to Sarasota for spring training 1957. Veteran pitcher Larry Jansen had seen him play and said, “Aspromonte was a pepper-pot with the San Francisco club all year. He deserves a chance to play in the big leagues — off his hustle alone.”5

Aspromonte got in some extra work by playing winter ball for Mayaguez in Puerto Rico. In February, he married Shirley Lorraine Ennis of Seattle.

In December Higgins had said shortstop was the team’s weak spot and he said the position was up for grabs between Billy Consolo, Ted Lepcio, and Aspromonte. Don Buddin was in the Army. Higgins was high on Aspromonte

As it worked out, Billy Klaus won the job by mid-March, and on April 2 Aspromonte was optioned back to the Seals.

He had his best year yet in 1957, playing under manager Joe Gordon, and was batting .334 with 73 RBIs when he was called up to the Red Sox after Ted Lepcio’s wrist was broken during the August 29 game in Detroit. The Boston Globe told fans that he “is a slick fielding second baseman who looms as next year’s regular at the position.”6

The Seals won the Coast League pennant, Aspromonte’s average won the Coast League batting crown, and he was named the league’s all-star second baseman.

His first appearance in the major leagues was at Fenway Park as a defensive replacement at second base in the ninth inning of the second game of the September 2 doubleheader against the Washington Senators. He fielded the last play of the game, securing an 8-7 Red Sox win.

Aspromonte’s first big-league base hit came on September 4 at Yankee Stadium. Given his first start, he grounded out his first time, hit a sacrifice fly and earned his first RBI, and collected three singles in the game, won 7-5 by the Red Sox in 11 innings. George Kell was impressed by the poise Aspromonte had shown during three games against the Orioles. “Aspromonte seems to have all the essential baseball instincts,” he said. “He always seems to be with the play, in the right place at the right time. That’s very important. He moves around gracefully and quickly. He runs bases, too. But he needs to stop pushing at bat and start pumping.”7 Jimmy Piersall added that Aspromonte was “the best second base prospect we’ve had since Bobby Doerr.”8

Aspromonte appeared in 24 games for the Red Sox, hitting a very respectable .269 while drawing 17 walks for a .396 on-base percentage. That winter he played in Venezuela for the Licoreros de Pampero.

But Don Buddin was back and the Red Sox acquired Pete Runnels in late January. Aspromonte battled hard in spring training, and Higgins decided to ride a hunch, naming him Red Sox starting second baseman for Opening Day. But in his first 18 plate appearances, all Aspromonte mustered was one single. After five games, the Red Sox losing four of them, Higgins benched him in favor of Billy Consolo. He had one more at-bat for the Red Sox, a pinch-hit single in the top of the bottom of the ninth in a 2-0 loss to the Washington Senators on April 25. A few days later, after more than a month of rumors, Aspromonte was a Senator, traded to Washington on May 1 for left-handed-hitting catcher Lou Berberet. The Red Sox were ready to go with Runnels (who hit over .300 the next five years and won two batting titles).

Aspromonte played in 92 games for the 1958 Senators, batting .225 with 27 RBIs. And then he played winter ball again, returning to Puerto Rico.

Reno Bertoia played 71 games at second base for the 1959 Senators; Aspromonte played in 52, and a couple of other players worked there, too — Johnny Schaive and Herb Plews. Manager Cookie Lavagetto seemingly never settled on any one player. The Senators finished in last place again. Aspromonte wasn’t happy about his playing time and wanted to be traded.9 Throughout his career, he was considered to be someone with a short fuse. In September 1960, Hal Lebovitz wrote, “His greatest enemy is his own temper. When he makes a mistake at bat or in the field, he fights himself.”10

Nonetheless, after the season, Aspromonte moved to Washington. And in late January he traveled to Europe with several others to give some baseball clinics under the sponsorship of the US Air Force.11

He pinch-hit three times for the Senators in April 1960, each time making an out. Billy Gardner had established himself at second base, so on May 15 the Senators made a move and traded Aspromonte straight up to the Cleveland Indians for outfielder Pete Whisenant.

He got his opportunity to play, and he excelled. He collected hits in six of his first seven games, and manager Joe Gordon was pleased. “I’ve liked him since I had him at San Francisco in 1957. I’ve always felt that if given a chance, he could play in the big leagues. Washington wasn’t playing him, so I went out and got him.12

Aspromonte played in almost all the remaining games — 117 of them — and batted for a .290 average, practically the best of his career, as well as setting career marks in both home runs (10) and runs batted in (48). He scored 65 runs, likewise a career high. He credited Gordon for having faith in him and giving him confidence.13

When the American League expanded by adding two new franchises for 1961, the Los Angeles Angels and a new Washington Senators (the team that had been the Senators in 1960 relocated to Minneapolis for 1961), the two new franchises were each able to select 28 players from the eight AL teams, at a price of $75,000 per player. Aspromonte was not among the players the Indians protected. On December 14 he was selected by the new Washington club as the 26th overall selection in the expansion draft, and was then traded on the same day to the Angels for Coot Veal.

He’d been miffed at being placed on the “rinky-dink list” — in other words, the list of those not protected — given that he had outhit every second baseman in the league both in average and home runs, but suggested that perhaps he’d done too well and thus shown up Cleveland’s GM Frank Lane because Lane had traded for Johnny Temple (from the Cincinnati Reds) and Aspromonte had beaten him out for the second-base slot. “I told my wife I’d end upon that list, and I did.”14

Aspromonte had to fight for what he achieved and he didn’t apologize for it. “Don’t ask me to smile when I play ball,” he said around this time with what one writer termed a growl. “When I’m on the ballfield I have no time for friends. This is a dog-eat-dog business.”15 The writer said he had a reputation of something as a hothead who “always took his baseball seriously — too seriously, many thought.”

This was something Aspromonte realized, later in life. “I grew up in Brookyn — Bensonhurst, New York — not Westchester County, in a neighborhood of tough kids where you had to fight your way through everything if you wanted to get to the top. Most of my friends were fighters, and I was one of them. But eventually I found out you don’t fight in professional sports. All you can do is try the best you can with whatever God-given ability you have and hope it’s good enough.” He added, “If there was any time in my life I needed someone to talk to, it was then, when I was in the big leagues. But in those days they didn’t have guys like that, guys who could sit down with you and talk to you and help you. They just threw you out there, and if you produced, fine. And if you didn’t produce, there were plenty of other players out there waiting for their chance. …

“Once I got to the major leagues I started fighting myself, primarily because I was never satisfied. I always wanted to be better. … I was one of those guys who could not shake off a bad situation. I analyzed myself to death, wondering what the hell I did that was wrong. Why I didn’t stick with any one organization. … Unfortunately, I didn’t realize until it was too late that it was my temper, my disposition that kept me from being the player I should have been. It’s something I’ve always regretted.”16

Aspromonte definitely got a chance to play for the Angels. And in mid- to late April, he said he was happy with his situation.17 He played in almost every one of their games, but wasn’t producing. After the first day of July, he’d been in 66 games but was batting only .223 with 14 RBIs. He was placed on waivers and selected back by the Cleveland Indians, for $20,000.

He played about the same for the Indians as he had for the Angels, batting .229 in 22 games, with five RBIs.

Building on the idea of the baseball clinics he’d taken part in for the Air Force, Aspromonte set up his own company named Major League Baseball Clinic for Boys. His board had more than a dozen major leaguers on it.18 Bob Turley, Gus Triandos, and Bob Nieman were the key others involved.19 The first clinic in the D.C. area drew 1,800 kids.

Aspromonte was only 30 years old but did not get off to a good start in 1962. The Indians played him in 20 games, with only 34 plate appearances, by the end of June. He was batting .143 with just one RBI. On July 1 his contract was purchased by the Milwaukee Braves. He had a much better second half, batting .291, albeit in only 34 games.

On October 16 the Braves assigned Aspromonte’s contract to Louisville. And on December 2, they traded him to the Chicago Cubs for Jim McKnight. The Cubs wanted him for bench strength.

Aspromonte’s last year in the majors was 1963, a year that also saw him return to the minor leagues. He was with the Cubs through the game of June 21, though after the first 10 games of the season he’d almost only been used as a pinch-hitter. He was batting .147, with four RBIs. On June 24, he was optioned to the Triple-A Salt Lake City Bees. He played in 64 games there, batting .236.

Aspromonte trained with the Cubs in 1964, but on March 30, he was placed on waivers for the purpose of giving him his unconditional release. Unclaimed, he was released on April 3.

On April 23, Aspromonte found a new home, signing with the Central League’s Chunichi Dragons of Nagoya, Japan. He had a good year, batting .282 in 101 games, and — at least as importantly — very much enjoyed the experience. He later told Russ Schneider of the Cleveland Plain Dealer, “When the game gets into your blood as it got into mine, you do everything possible to keep on playing.”20

After the season, Bud Collins of the Boston Globe caught up with Aspromonte and was told: “The only person higher than me in this country is the emperor. That’s the way it is here, being a major league ball player. You’re right below the emperor as far as the people are concerned. Most of them can’t name the top people in the government, but they know all the ballplayers, and they really idolize us. I never saw anything like this in the States.”21 He also took in the 1964 Olympics at Tokyo. The only bad feature, he said, was that his wife, Lorri, was lonely.22

Aspromonte was invited back for a second season, and was asked to do some scouting of other American players. Paul Foytack was one he brought to the Dragons for the 1965 season.23 Aspromonte hit .256 in 78 games.

In 1966 he played a third year in Japan, for the Taiyo Whales, and hit an Opening Day home run. He played in 116 games and hit for a .276 average, finishing his professional playing career on a high note. Getting a little older, he wasn’t able to play at the level he wanted to, so he retired from playing and took some time off. “I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I was getting offers to come back in baseball, but I didn’t think I wanted to do that.”24 He did a bit of broadcast work in Washington, but then got a call from Cleveland Indians farm director Hank Peters asking if he would take care of a need they had. On June 1, 1968, he signed to manage Sarasota, the Indians’ rookie league club in Florida. “It was a great experience for me. Just terrific.”

In 1969 Aspromonte was hired to manage the Class-A Reno Silver Sox in the California League, an Indians affiliate. They won 72 and lost 68, and Aspromonte got a promotion to Triple A, managing the Wichita Aeros of the American Association. He outlined the sort of work that a low-level minor-league manager needed to do — serve as trainer, traveling secretary, personal adviser, policeman — everything short of driving the bus — and then to write reports for the higher-ups, too. But he realized it was an apprenticeship. His goal was to become a major-league manager.25

They had two seasons of sub-.500 ball, but any manager is limited by the players he is provided. The Indians believed he had done a good job and in November 1971 he was named manager of the big-league club for 1972. He was taking over a team that had finished in last place in the AL East in 1971, with 102 losses, tied with the 1914 team for the most losses in franchise history.

One of the first moves the Indians made was a winter meetings deal to trade Sam McDowell to the San Francisco Giants for Gaylord Perry and infielder Frank Duffy. McDowell had been disaffected and even left the team for a week during the 1971 season. GM Gabe Paul said, “Duffy was the key man in the deal.”26

The Indians won 12 more games in 1972 than in 1971 and edged up to fifth place. Duffy didn’t help much with offense. Graig Nettles drove in 70 runs, leading the team in RBIs. They did need more offense. But Gaylord Perry had a terrific year, winning 24 games to lead the league (tied with Wilbur Wood), with a 1.92 ERA. There were charges all year that Perry was throwing a spitball, but the charges weren’t anything new, and no umpire ever found evidence.27 Perry was happy enough that people suspected something; he figured it gave him a psychological edge.

Immediately after the season was over, Aspromonte was signed again to manage in 1973. Right after Christmas, Gabe Paul went off to scout players in Puerto Rico and Aspromonte did the same in Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico.

In 1973 the Indians regressed as far as wins and losses, dropping 91 games and returning to the cellar. Perry was 19-19, his ERA up to 3.38. Duffy did better. Leading the team in RBIs, with 73, was left fielder Charlie Spikes. Nonetheless, Aspromonte was rehired, even earlier this time, in mid-September.

A new rule was put into effect before the 1974 season, allowing an umpire to use his judgment to charge a pitcher with throwing a spitter even if he couldn’t find any evidence. The first player charged was Gaylord Perry.28 It didn’t seem to negatively affect him; he won 21 games and he recorded a 2.51 ERA. The Indians improved by six games in the loss column, and they finished in fourth place. It was the highest they’d been since 1968. As late as July1, they’d been only 2½ games out of first. Aspromonte still received some boos from the stands, prompting his father, Angelo, to ask during a visit in August, “Everywhere, people tell me my kid is doing a good job, But here in Cleveland, everybody boos him the minute he pokes his head out of the dugout. Why do the people here do that?”29

It was hardly “everybody” that booed Aspromonte, of course. And he had earned the praise of fellow managers around the league — Dick Williams of the Angels said he “deserves to be rehired,” and that doing so in August might give the Indians players a positive boost. Chuck Tanner of the White Sox said, “You don’t turn things around this fast normally, but the Indians have. … They’ve had one of the greatest turnarounds in baseball history.”30 The one voice that remained conspicuously silent was that of GM Phil Seghi.

Just before the end of the season, it was announced that Aspromonte’s contract would not be renewed. For some reason, Seghi went a little further and said that Aspromonte would not be with the organization in any capacity. There was speculation that the Indians were going to hire Frank Robinson as the first black manager in the majors.31

Robinson was indeed hired. After his first year on the job, Robinson wrote a 1976 book with Dave Anderson of the New York Times. In the book, Frank: The First Year, Robinson said, “Shortly after I joined the Cleveland Indians for the last three weeks of the 1974 season, I realized this was a ball club in trouble. The dugout was virtually segregated. On one side was the manager, Ken Aspromonte, with almost all the white players. On the other side was Larry Doby, a black coach, with all the black players. I sat here and there, mostly in the middle. Any ball club that’s split along racial lines like that had to be in trouble.”32 The Plain Dealer article on the book noted that Aspromonte had privately claimed that Doby had undermined him, and that Robinson pretty much agreed. That’s why he chose not to retain Doby on the coaching staff. “I didn’t keep Larry Doby because he had shown me he wasn’t loyal to the manager. Doby was hoping to be the first black manager himself. But splitting the team racially wasn’t the way to do it.”33

Aspromonte said, “I tried my best,” and added that he could walk out “with my head up high.”34 Later, he was less diplomatic, saying that he had been left with a sour taste, noting that attendance had nearly doubled (from 615,107 in 1973 to 1,114,262 in 1974) and that Seghi had awarded himself a two-year contract.35

In January 1975 Aspromonte was hired as an official host at Caesars Palace hotel and casino in Las Vegas. He was “delighted by the thoughtfulness of 15 of his former players who stopped in Las Vegas to say hello when they were on their way to the Indians’ [spring-training] camp in Tucson.”36 Originally, in effect, a greeter, he said a couple of months after hiring that he was still a manager, “in the management process,” as he put it.37 He worked looking after VIP guests. His pay remained the same, with better fringe benefits, he said, and he acknowledged that being fired so suddenly, with there being no sense of loyalty, left him with the aforementioned sour taste.38

In November 1975, Bob and Ken Aspromonte were selected from among 950 applicants for the Coors Beer distributorship in Houston. Ken’s plans were to remain with his position in Las Vegas, while Bob was going to actively run the distributorship.39

He hadn’t given up on baseball, however, and was reported to have applied for open managerial slots in Milwaukee and Minnesota, and to become GM of the Houston Astros.40

In January 1976, Ken left his position with Caesars Palace and managed the Coors distributorship with brother Bob. In the early 2000s, Bob and Ken sold the majority of their interest in Aspromonte Coors Distributing, and Coors and Miller merged into Faust Distributing Company. “We had the distributorship for 27 years, Bobby and I. We sold it. I’m semiretired now, watching over my investments. I’m a pilot. I fly my own plane. I play golf once or twice a week. I work out, and take care of my health. That’s about it.”41

Asked where he flies, Ken said, “I fly over Louisiana, New Mexico, North Texas. I flew to Seattle. Sometimes we take care of those people who can’t get to a medical center, and we fly them back and forth. I fly a Cirrus. My plane is now about 10 years old. I bought it new in 2007. It’s a plane with a parachute. They’ve already saved over 100 people who lost control of their plane. You pull this lever above your head and a rocket goes off and this parachute goes off. The whole plane comes down and it’s like you fell from maybe eight or nine feet.”42

“Bobby’s got a little more of a problem. He’s got diabetes. It’s demanding.” The two brothers remain in very close touch. “He’s right here. I talk to him every day. We see each other every day.” Ken had no children but he and his wife, Shirley, have been married 60 years as of February 2017.

Like many former ballplayers, Aspromonte’s kept busy by people sending him baseball cards to autograph. He follows baseball, of course, but other than a few people like Dusty Baker and Bruce Bochy, he no longer knows that many people in the game, once Tommy Lasorda left, and Tony La Russa. He did enjoy coming back to Boston in 2012 when the Red Sox celebrated the 100th anniversary of Fenway Park and brought back over 100 former players for ceremonies. He remembered when he first was brought up to Boston, he was placed next to Ted Williams. The Red Sox slugger had three adjacent lockers, one for his civilian clothes, one for his bats, and his uniforms. “And I had three nails next to him. Nails! Johnny Orlando, the clubhouse guy was pretty tough to me. ‘You haven’t made it yet, kid.’ That was tough. But I enjoyed it.”43

Last revised: June 27, 2018

Acknowledgments

This bio was fact-checked by Carl Riechers and edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Aspromonte’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, Joe Wancho, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Phil Pepe, “Baseball Always a Family Affair for Aspromontes,” New York Daily News, May 27, 1972: 23C. Pepe called the elder Aspromonte “Charles.” Russell Schneider in the Cleveland Plain Dealer (1974) called him Angelo.

2 Ken Aspromonte, “Key to a Career,” Boston Traveler, March 27, 1958: 35.

3 Ibid.

4 Joe Cashman, Red Sox Kids Host to Cardinals,” Boston Record, February 18, 1956: 25.

5 Clif Keane, “Ex-Brave Thiel, Aspromonte Join Hose in Spring,” Boston Globe, September 28, 1956: 26.

6 “Sox Home for Twin Bill,” Boston Globe, September 2, 1957: 61.

7 Ed Rumill, “Baltimore Veteran Likes Sox Rookie,” Christian Science Monitor, September 9, 1957: 11.

8 Mike Gillooly, “Fans Predict Vernon Will Wind Up Yankee,” Boston American, January 30, 1958: 33.

9 Bob Addie, “Bob Addie’s Column,” Washington Post, September 27, 1959: C2.

10 Hal Lebovitz, “Hats Off … Ken Aspromonte,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1960: 23.

11 “3 Nats Play in Germany,” Washington Post, January 22, 1960: D1.

12 Ed Rumill, “Ken Aspromonte Key Utility Player in Flag Drive of Cleveland Club,” Christian Science Monitor, June 8, 1960: 16.

13 See, for instance, Milton Richman (United Press International), “Ken Aspromonte Is Surprise of American League Season,” Atlanta Daily World, July 29, 1960: 6.

14 Dave Brady, “Aspromonte Demands 100% Raise of Angels,” Washington Post, January 25, 1961: 22.

15 Norman Miller, “Aspromonte Likes Role of an Angel,” Jersey Journal (Jersey City), April 20, 1961: 14.

16 Russell Schneider, Whatever Happened to Super Joe? Catching Up With 45 Good Old Guys from the Bad Old Days of the Cleveland Indians (Cleveland: Gray & Company, Publishers, 2006), 71-72.

17 UPI, “ ‘Angel’ Aspromonte Happier With New Outlook on Game,” Los Angeles Times, April 21, 1961: C4.

18 Details of how the clinic planned to operate may be found at Bob Addie, “Bob Addie’s Column,” Washington Post, January 12, 1962: A23.

19 See also Dave Brady, “Baseball Needs More Youngsters and Aspromonte Is After Them,” Washington Post, January 21, 1962: C3.

20 Russell Schneider, “Manager’s Job a Back Breaker,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 29, 1969: 31.

21 Bud Collins, “Aspromonte Up With Hirohito,” Boston Globe, October 28, 1964: 21.

22 Bob Addie, “A Special Youngster,” Washington Post, December 20, 1964: C2.

23 UPI, “Paul Foytack in Japan for Comeback Try,” Chicago Tribune, March 7, 1965: B2.

24 Ken Aspromonte, author interview, April 20, 2017.

25 Russell Schneider.

26 “Tribe Trades McDowell for Giants’ Perry,” Washington Post, November 30, 1971: D1.

27 Ed Rumill, “For Perry, a Rumored Dab’ll Do It: ‘Let Them Holler,’” Christian Science Monitor, May 31, 1972: 12.

28 UPI, “New Spitball Rule Invoked vs. Perry,” Boston Globe, April 7, 1974: 64.

29 Russell Schneider, “The Boos … They Tear Up Aspro’s Mom, Dad,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 20, 1974: D1.

30 Russell Schneider, “Seghi Silent in Shower of Bouquets for Aspro,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1974: 19. Schneider, incidentally, was at one point “roughed up” by an Indians coach, “and it took place in the manager’s office with Ken Aspromonte present.” Chuck Heaton, Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 26, 1979: 50.

31 Associated Press, “Indians Fire Aspromonte,” Atlanta Constitution, September 28, 1974: 2C.

32 Dan Coughlin, “Player Conflicts Spice Robbie’s Diary,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 29, 1976: 29.

33 Ibid.

34 Gerald Eskenazi, “Aspromonte: ‘I Tried My Best,’” New York Times, October 10, 1974: 62.

35 Regis McAuley, “Fuse Finally Burns,” Cleveland Press, undated May 1975 clipping in Aspromonte’s Hall of Fame player file.

36 Jerome Holtzman, “ ‘Tardy’ Padres Saved $30,000,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1975: 54.

37 Byron Rosen, “Aspromonte Is Still a ‘Manager,’” Washington Post, March 13, 1975: E3.

38 Associated Press, “Aspromonte Sour After Losing Cleveland Job,” Los Angeles Times, May 6, 1975: OC-B8.

39 “Aspro Scores From New Base,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 12, 1975: 4A.

40 Russell Schneider, “More Trades Ahead,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 23, 1975: 50.

41 Ken Aspromonte, author interview, April 20, 2017.

42 For an explanation of how Cirrus’s parachute system works, see youtube.com/user/CirrusAircraft, and to see a video showing one deploy, see https://youtube.com/watch?v=az12JHwm7no.

43 Ken Aspromonte, author interview, April 20, 2017.

Full Name

Kenneth Joseph Aspromonte

Born

September 22, 1931 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.