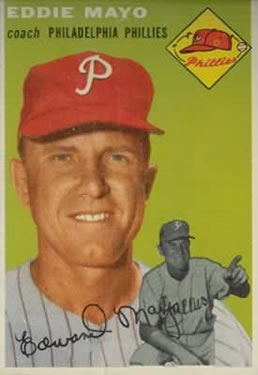

Eddie Mayo

In 1945, The Sporting News reckoned Eddie Mayo as “an excellent example of the Salvation Army adage, ‘A man may be down, but he is never out.’”1 Acquired by the Detroit Tigers a year earlier after he had failed in several attempts to stick in the big leagues, the 34-year-old infielder helped pace the club to within one game of the AL pennant. One season later Mayo captured The Sporting News MVP award while leading Detroit to its second world championship.

In 1945, The Sporting News reckoned Eddie Mayo as “an excellent example of the Salvation Army adage, ‘A man may be down, but he is never out.’”1 Acquired by the Detroit Tigers a year earlier after he had failed in several attempts to stick in the big leagues, the 34-year-old infielder helped pace the club to within one game of the AL pennant. One season later Mayo captured The Sporting News MVP award while leading Detroit to its second world championship.

Edward Joseph Mayoski was born on April 15, 1910, the youngest of four children of Polish immigrants Alexander and Sophie (Chalek) Mayoski, in Holyoke, Massachusetts, 90 miles west of Boston. His parents had met at a community dancehall after arriving separately in the United States in the 1890s. The young couple settled in New Jersey before moving to Massachusetts briefly around the time of Eddie’s birth. Around 1912 the family returned to New Jersey and settled in Clifton on the western outskirts of metropolitan New York City. At various points in his life Alexander, a versatile laborer, worked as a mechanic and carpenter. Years later both he and Sophie were employed as weavers at a Clifton silk mill. Sometime in the 1920s Alexander shortened the family’s surname to Mayo.

“We were an athletic family,” Eddie recalled years later. “My brother played [semipro base]ball, and one [of my] sisters . . . was kind of a tomboy. . . . We lived a block or two away from a beautiful [ball]park in Clifton.”2 Eddie eventually joined his brother in sandlot play. He attended Clifton High School where he was a standout athlete in baseball and especially basketball. After graduating from high school around 1928, Mayo received an athletic scholarship to play basketball for Providence College in Providence, RI. Inexplicably, there is no indication he accepted this offer. According to the 1930 US census, the 19-year-old was living with his parents in Clifton while working in a garage.

Mayo, a left-handed hitter, continued playing semipro ball, and in 1931 he attended a New York Giants tryout. Turned away due to his slight build, a year later he caught the attention of Tigers scout and former minor leaguer Michael McCully.3 Inked to a $175/month contract, Mayo was assigned to the Class-C Huntington (WV) Boosters in the Middle Atlantic League. He placed among the team leaders in nearly every offensive category, and spent the bulk of his time playing third base. Advanced to Class-A Knoxville Smokies in the Southern Association in the closing weeks of the season Mayo continued to impress. Mayo is a “fine young player . . . headed for the majors in another season,” wrote The Sporting News. “[H]e will be one of the leading lights next summer.”4

During spring training in 1933 Mayo developed a sore right (throwing) arm, the first of many injuries that would dog him throughout his career. The injury did little to slow his bat though as he split the season between the Smokies and the Johnstown (PA) Johnnies in the same circuit. Playing for the Johnnies on July 28 Mayo got four hits to lead his club to a 24-7 win over the Wheeling Stogies. He finished the season’s last 79 games with a .298 average. In April 1934, in a series of undisclosed transactions, Mayo was acquired by the AA Baltimore Orioles in the International League but returned to Johnstown shortly thereafter. When Johnnies player-manager Guy Sturdy jumped to the Orioles midway through the season, he tried to take Mayo with him. In the ensuing dispute between the Tigers organization and the Orioles, Mayo, on the cusp of an All-Star season, was declared a free agent by Commissioner Kenesaw Landis. Reclaimed by the Orioles, Mayo had played in only 17 games before suffering a broken finger on his right hand after taking a throw at second base. He ended up sidelined for the remainder of the season, but his short stint made a strong impression. Mayo’s work had impressed his manager, The Sporting News reported. “He hit hard and timely and handled himself well in the field.”5

Mayo’s work proved even more pleasing the following year. On April 28, he got three home runs and six RBIs in a rout of the Buffalo Bison. A month later he drove in four runs in a win over the Syracuse Chiefs. Then on June 30, Mayo lifted the Orioles into first place after his grand slam sent the Albany Senators to defeat. During the season, he particularly thrived on Sundays: 27-for-77 with 10 home runs. Mayo stirred the interest of several major-league clubs. He finished among the league leaders with career high marks in triples (10), home runs (25), and total bases (286), solid numbers stunted only by his insistence on playing through injury in the closing weeks of the season. Over the winter, he underwent surgery after learning the injury he had sustained was a hernia.

Baltimore couldn’t hold Mayo long. After a slow start to the 1936 season, he soon was hammering the ball at a .362 clip. On May 13, the Orioles traded him to the Giants for third baseman Joe Martin and $25,000.6 Promoted from Class-A to the big leagues before the season, Martin had been viewed as a potential replacement for aging veteran Travis Jackson. This experiment didn’t last: Mayo was now expected to fill this role. And on May 22, Mayo made his major-league debut in New York’s Polo Grounds against the Philadelphia Phillies. Spelling Jackson in a hopeless 15-0 drubbing, Mayo drew a walk in three plate appearances against Athletics righty Bucky Walters. A week later Mayo started in his first game against the Boston Bees and achieved his first major-league hit, an RBI single against veteran right-hander Ray Benge in the first inning.. Mayo collected two additional hits, scored two runs, and reached base four times that day as the Giants ran away with a 15-0 win.

On June 6, while in the middle of a five-game hitting streak, Mayo hit his first major-league home run, a second inning leadoff blow against St. Louis Cardinals righty Ed Heusser. A month later, he concluded a second five-game streak with his first triple, the fourth of four such blows in an inning that tied a NL record. But this second streak ended in a 3-for-34 slump that quickly relegated Mayo to the bench. He did not receive another starting assignment until the Giants clinched the pennant in late September. In the sixth and final game of the World Series against the New York Yankees, Mayo entered the eighth inning as a defensive replacement. Leading off the top of the ninth against reliever Johnny Murphy, Mayo popped out in foul territory to third baseman Red Rolfe in the Giants 13-5 loss.

Days after the Series ended, Giants manager Bill Terry hinted that Mayo’s days in New York might be numbered. “[T]he young Polish lad . . . hadn’t shown me enough,” Terry said.7 Several times in November as the Giants vainly attempt to acquire Cardinals flamethrower Dizzy Dean, Mayo’s name was floated alongside outfielder Hank Leiber, pitcher Hal Schumacher, and others. But on December 4 Mayo was sent to the Boston Bees for veteran infielder Mickey Haslin.

Boston saw the acquisition of Mayo as a godsend. Since the departure of Les Bell after the 1929 season, the Bees had trotted out no fewer than 21 third basemen during the following seven seasons. Mayo, the Bees anxiously hoped would arrest this revolving door. “I don’t believe that was a fair test for [him],” Boston manager Bill McKechnie said of Mayo’s time in New York. “I have had so many favorable reports on him from friends in the International League that I feel he is a better player than he showed.”8

But the Bees’ high hopes collapsed when Mayo started the 1937 season hitting only .175—11 hits in 63 at-bats. Now riding the bench following the team’s acquisition of veteran third baseman Gil English, Mayo made just three pinch-hit appearances in June. Mayo returned to the lineup after English was briefly sidelined in July, and the two platooned at third throughout the remainder of the season. On July 31, Mayo delivered a ninth inning pinch-hit RBI single with the bases loaded to lift the Bees to a 9-7 win over the Pittsburgh Pirates and finished the season with nine hits over 10 games. But his season numbers were terrible: .227/.293/.291 in 172 at-bats.

During the offseason Casey Stengel replaced McKechnie as manager, as the latter transferred to the Cincinnati Reds. The new manager, also an investor in the team, helped oversee a series of transactions that crowded the Bees outfield. On May 14, 1938, as veteran outfielder Debs Garms made his first appearance of the season at third base, Mayo was sold to the Chicago Cubs who assigned him to the Class-AA Los Angeles Angels in the PCL, an assignment Mayo initially balked at.. But shortly after he joined the club, Mayo’s bat got hot, and the Angels won 32 of 41 games to jump from sixth to first in the standings. Mayo finished the season with a .332 average and led the league in hitting. His play in the field also sparkled. Moved to second base, he established a league record 34 consecutive games without an error. Runner up to Seattle Rainiers right-hander Fred Hutchinson for the league’s MVP, the pennant winning Angels named Mayo the club’s most valuable player. During the offseason, The Sporting News contributor Bob Ray predicted that Mayo was “a cinch to go up to the majors” during the winter.”9

He forgot to say which winter, for despite major-league scouts regularly monitoring his progress, Mayo remained in Los Angeles for four more seasons. In 1940, he moved back to third base fulltime where his “inspired ball around the hot corner” contributed to a league record .983 fielding percentage.10 Two years later Mayo connected on three of his dozen season homers in consecutive at-bats, missing a fourth straight homer when he launched a pitch against the wall in Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field for a double. Mayo was beloved by teammates and fans alike. On “Eddie Mayo Night” on June 18, 1942, a large crowd reveled at the sight of their All-Star infielder being showered with gifts. Despite ankle, elbow, and other nagging injuries that occasionally sidelined him, Mayo earned the nickname “Steady Eddie” for his reliable presence both on and off the field. (For unknown reasons, he also earned the nickname “Hotshot.”)

The only downside to Mayo’s five-year tenure in Los Angeles came after a July 13, 1941, game against the Hollywood Stars in which he was ejected following a heated argument with the umpire on a close play at third. The next day he learned he was suspended from the league for one year after the umpire claimed Mayo spat on him, a claim that the veteran infielder vehemently denied. After receiving an avalanche of angry letters and petitions from fans and players alike opposing the suspension—a groundswell that included testimony supporting Mayo from the Stars players and manager—PCL president W.C. Tuttle conducted two hearings before upholding the decision. In August, Mayo flew to Cincinnati to appeal the suspension before the executive committee of the National Association. To his elation, the committee ruled in his favor a month later. “I told them if I hit the ball over the centerfield fence and the umpire calls it foul, I wouldn’t argue,” he cracked.11

One of the people who had been monitoring Mayo’s career in Los Angeles was Athletics coach and former PCL standout catcher Earle Brucker. On November 4, 1942, as Philadelphia sought to fill its service-depleted roster during the Second World War, Brucker convinced Athletics owner-manager Connie Mack to select Mayo in the rule 5 draft. Mayo and veteran outfielder Jo-Jo White went on to be appraised as “the backbone of the team” during the club’s Wilmington, DE, based spring training.12 But days before the start of the season, having won the third base job, Mayo suffered retinal hemorrhage in his left eye when a ricocheted throw in a spring training game struck him in the face. The hemorrhage spawned a blind spot that did not affect his fielding, but did compromise his hitting.13 Except for a three-week 26-for-82 hot streak in June, Mayo managed only a meager .219 for the season in 471 at-bats. On September 27, six days before the end of the season, he was traded to the Red Sox with veteran outfielder Johnny Welaj for 24-year-old righthander Norm Brown. Mayo was immediately assigned to the Class-AA Louisville Colonels in the American Association but did not report there.

Five weeks after the trade, as Mayo contemplated retirement, the Tigers selected him in the rule 5 draft, and for the same reason the A’s did a year earlier—insurance against the wartime draft. Luckily, Mayo’s blind spot cleared completely in the offseason, and he looked forward to redeeming himself in the 1944 season. He began the year at shortstop and moved to second base when Joe Hoover, a late report to spring training, was ready to resume play. On May 14, following a slow offensive start, Mayo hit a home run, double, three singles, and collected five RBIs in a doubleheader sweep of the Red Sox. A month later he delivered a seventh inning game-winning bases loaded single to lead the Tigers to a 7-3 comeback over the St. Louis Browns. Mayo played all 154 games of the season and was considered the “sparkplug in [the Tigers] rise in [the]flag race,” wrote Sam Greene in The Sporting News. “He’s a throwback to the old school, always hustling himself and always chipping in with conversation to keep the other fellows on their toes.”14

Even sweeter, Mayo’s defense was nearly flawless: he led the league, turning 120 double plays as a second baseman, and his 498 assists trailed only Cleveland Indians shortstop Lou Boudreau for the AL lead. Though the Tigers surged to the end of the season with 41 wins in their final 57 games, it was not enough to hold off the hard-charging Browns who won the franchise’s first and only pennant on the last day of the season. Mayo had just finished his best year ever: he hit .285, with 10 homers, a .752 OPS, and nice 4.6 WAR. He even managed to lead the big leagues in sacrifice hits with 28. In 1945 the Tigers left nothing to chance, never relinquishing a stake in first place after June 12. Three days earlier Mayo delivered a ninth inning two-run triple to lead the Tigers to a 7-6 comeback over the Chicago White Sox. On June 30, he practically supplied Detroit’s entire offense with two doubles, three RBIs, and a run scored in the team’s 4-1 win over the A’s.

Three weeks later, while in route to a league leading .980 fielding percentage for second basemen, Mayo started the league’s only triple play of the season after making a leaping catch on a liner from Washington Senators shortstop Gil Torres. (A year later, in what quite likely the only instance in major-league history in which two triple plays involved the same batter and fielder, Mayo snagged a liner off Torres’ bat and turned another triple-killing after the ball deflected off pitcher Hal Newhouser’s bare hand.) Mayo played every inning of every game through August 6 before being benched with a shoulder injury on a throw in the fifth inning of a doubleheader’s second game. This injury would plague Mayo for the rest of his career. Returning with a fury two weeks later, he collected 29 hits in 70 at-bats through September 8, including a ninth inning three-run homer against Yankees reliever Bill Bevens in a comeback win over New York.

Mayo was named to the AL All Star team and, though an official game was not played, he participated in several exhibitions on behalf of the war relief fund.15 The Sporting News chose Mayo, among the team leaders in nearly every offensive category, as the league’s MVP, but the BBWA deviated, however, and chose his teammate Hal Newhouser, a 24-game winner and future Hall of Famer. Mayo finished second. “He is the inspiration of our club,” said Detroit manager Steve O’Neill. “I’d like to have four infielders like him.”16

The Tigers required the full seven games in the World Series to dispose of the Cubs and capture the world championship. On October 10, Chicago shortstop Roy Hughes hit a ninth inning leadoff single in final game in a last-ditch effort to overcome a 9-3 deficit. Two outs later Hughes was forced at second to end the game. Mayo caught the ball from shortstop Skeeter Webb, and two reports indicate he walked into the clubhouse and either gave the ball to Tigers owner Walter Briggs directly or via O’Neill. But the Chicago Tribune reported that “Mayo caught the ball, dropped it on the field and Hughes picked it up. H[ughes] kept the ball and eventually donated [it] to the Ohio Baseball Hall of Fame. When the museum closed . . . Grant DePorter, who owns the Harry Caray restaurant chain,” ultimately acquired the ball for nearly $9,000.17 But because of this uncertain chain of custody, the identity of the “true ball” remains a mystery to this day.

Injury dogged most of Mayo’s 1946 season. Despite missing most of spring training with a back ailment—a recurring problem for Mayo over the preceding three years—he opened the season with a hot bat, getting six hits in his first 13 at-bats and delivering a 10th inning RBI double against future Hall of Famer Bob Feller on April 21 to give the Tigers a 3-2 win. A month later, during a remarkable stretch of wildness from White Sox lefthander Thornton LeeMayo got the only hit of the frame, a bunt single, during a second inning six-run outburst in the Tigers 6-5 win.

But in a June 3 game at Washington, Mayo and centerfielder Hoot Evers knocked each other unconscious in the third inning when they collided chasing a shallow fly ball. Carried off the field on stretchers, both spent several days recovering at Georgetown University Hospital. Sidelined until July 13, Mayo’s return got cut short by a second collision six days later, this time with Senators infielder Jerry Priddy, that injured his back. Mayo tried to persevere, making a pinch-hit appearance on July 25, before the pain became too much to bear. Attempts to return ended when he was diagnosed with a ruptured disk. On August 7, Mayo underwent surgery at Detroit’s Henry Ford Hospital.

In February 1947 Mayo, believing himself fully recovered from the operation and seeking a jump on his comeback campaign, reported early to the Tigers spring training. Valiant as his efforts were, his “play in exhibition games [was deemed] less than adequate.”18 These challenges continued into the regular season: he hit only .192 with one home run and seven RBIs in his first 151 at-bats. Though Mayo rebounded in the second half of the season, including a career best 20-game hitting streak, the Tigers were actively scanning the trade circuit for somebody to replace their aging 37-year-old.

Mayo surprised everybody as the 1948 season commenced. On the strength of a strong spring training, he wrestled the starting second base job from all comers. He opened the season with a 12-game hitting streak and flirted with a .300 average into near-mid May. But a week later he fell into a 3-for-45 slump that compelled O’Neill, albeit one of Mayo’s biggest backers, to start platooning him with infielder Eddie Lake. Around this same time, the Detroit front office offered Mayo and outfielder Dick Wakefield to the Cubs for second baseman Don Kolloway, a swap the Cubs reportedly declined.

With only 143 at-bats in the second half of the season, Mayo made the most of his limited opportunities. On July 25, he got a career high five hits in a 10-2 win over the Athletics. Mayo’s three RBIs on September 22 provided most of the Tigers offense in a 5-1 win over the A’s again. On October 3, his last major-league appearance, he got two hits and an RBI in a 7-1 win over the Indians. The Tigers had already concluded during the season that Mayo had slowed “to the point where he [was] a defensive liability.”19 In November, they asked him to retire and take a managerial posting in the farm system.

Not prepared to conclude his playing career, Mayo spent the offseason petitioning several clubs—unsuccessfully—for a shot to stay in the majors. Though committed to moving 27-year-old shortstop Neil Berry to second—a commitment lasting just 18 days when the club acquired Kolloway from the Cubs on May 7—the Tigers granted Mayo an opportunity to make the team in spring training. But in late March 1949, facing the possibility of an outright release after an injury-plagued camp, Mayo accepted an assignment to the American Association as player-manager of the newly-affiliated Triple-A Toledo Mud Hens.

Though realizing little success as a manager—a .422 winning percentage over two seasons, a performance that Tigers GM Billy Evans chalked up to the club’s poorly stocked farm—Mayo did get credit for getting “the ‘mostest’ out of the ‘leastest’ . . . [by] having the most aggressive club in the league.”20 After the 1950 season Mayo bolted the Tigers organization and accepted the third base coaching job for the Red Sox under his old manager and stalwart supporter Steve O’Neill (who had left Detroit three years earlier). In 1952, the pair switched leagues to join the Philadelphia Phillies. Mayo’s lengthy major-league tenure ended after the 1954 season, some months after O’Neill was fired.

During his career, Mayo spent at least one offseason barnstorming with Hank Greenberg’s All Stars before finding work outside of baseball. A favorite on the rubber chicken circuit, he joined Joe DiMaggio at the speakers’ podium during the February 6, 1945 BBWA’s winter meeting in Union County, NJ. Three weeks later Mayo was a guest speaker at the third annual Old Timers dinner in Patterson, NJ. In the 1930s Mayo had partnered with his brother-in-law in a milk delivery business, as both dreamed of becoming dairy farmers. During the the war, he worked in a munitions factory near his home in New Jersey. After baseball, Mayo returned to New Jersey and ran a successful tile business before venturing into ownership of several restaurants. In 1989, Clifton, the town which had once organized an “Eddie Mayo Day” at Yankee Stadium in September 1945, feted their hometown hero again by naming a baseball field in his honor.

In the decades following his baseball career Mayo enjoyed reunion events with former teammates in Detroit, Baltimore, and other cities. He retired from the restaurant business around 1989 and moved to the Eastern Shore of Maryland before eventually settling in Southern California. Once considered “one of the nicest guys inside or out of baseball,” in retirement Mayo continued to extend himself by working with several children’s charities.21 He had already earned that reputation during his playing career. Major-league infielder Eddie Miller—who never played with Mayo—and Tigers clubhouse attendant Alex Okray, for example, were both inspired to name sons after him.22

In 1936, Mayo met New York City native Margaret Mary Hussey at the Polo Grounds. Six years younger than he, she was not unfamiliar with baseball, her accountant-father had once owned several semipro clubs in New York in the early 1900s. In November 1937, the couple married and went on to have four children. In 1976, Margaret died in Salisbury, Maryland, and later that year Mayo married her older sister Virginia, herself a widow. This union lasted until her passing in 2000 in Banning, California, 80 miles east of Los Angeles. On November 27, 2006, seven months after his 96th birthday, Mayo died in Banning. At the time of his passing he was the oldest living Detroit Tiger. Mayo was buried in Fairfax Memorial Park, Vienna, Virginia.

Around the turn of the 20th century business magnate John D. Rockefeller claimed, “I do not think that there is any quality so essential to success of any kind as the quality of perseverance.” Mayo certainly represented this quality. After failed attempts to stick in the major leagues, he returned during the war years to capture both a World Series ring and a Sporting News MVP award.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Tom Schott and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com. The author wishes to thank Edward Joseph Mayo, Jr. and Dobb Mayo, the ballplayer’s son and grandson respectively, for their valuable assistance.

Notes

1 “What Makes Most Valuable Player?” The Sporting News, October 4, 1945: 16.

2 Richard Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It: The Golden Age of Baseball in Detroit (Detroit, MI.: Wayne State University Press, 1991), 315.

3 Other sources indicate that Mayo was signed by scout Billy Doyle or former major league infielder Ike McAuley.

4 Bob Murphy, “He Likes Knoxville and Says He’ll Stay,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1932: 6.

5 Randall Cassell, “Baltimore Just About Set,” ibid., January 31, 1935: 3.

6 Another source indicates $15,000.

7 Daniel M. Daniel, “Terry Disappointed at Losing Collins,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1936: 3.

8 Frederick G. Lieb, “McKechnie, Visualizing Honey of a Bee Mound Staff, Bemoans Conditions Making Him ‘Defensive Manager,’” ibid., March 11, 1937: 3.

9 Bob Ray, “Angels Glide to Flag on Wings of Six in Row,” ibid., September 22, 1938: 14.

10 Ibid., “Statz Trying to Smooth Rough Spots on Mound,” May 16, 1940: 1.

11 “Mayo ‘Welcome Home’ at Los Angeles, Sept. 16,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1941: 2.

12 Stan Baumgartner, “Pair of Young Phils Give Harris a Thrill,” ibid., April 15, 1943: 9.

13 Norman Macht, “Connie Mack and Wartime Baseball—1943,” 2013 The National Pastime. Accessed February 12, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2l2YiAl ).

14 Sam Greene, “Tigers’ Hi-Yo Spirit Laid to Eddie Mayo,” The Sporting News, June 8, 1944: 9.

15 “Tigers’ Triple Killing Against Nats Just a Re-Take of Play Last Year,” ibid., May 16, 1946: 24. In December 1945, Mayo joined Babe Ruth, Dizzy Trout, and other baseball celebrities at a Mt. Vernon, New York bowling tournament that raised $149,354 for a similar charity.

16 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Motor City Sparkplug and Hex Machine, Too,” The Sporting News, October 4, 1945: 10.

17 Kristen Bentley, “Detroit Tigers: You Never Know Who You’re Going to Meet,” Motor City Bengals, February 15, 2017. Accessed February 21, 2017 (http://bit.ly/2lHTqB9 ).

18 H. G. Salinger, “Tigers Visualize Vico as Star—But He’s a Year or Two Away,” The Sporting News, April 2, 1947: 6.

19 Watson Spoelstra, “Berry Looks Like Cream of Tiger Keystone Bidders, ibid., September 15, 1948: 8.

20 Sam Levy, “6 of 8 Association Pilots Likely to Stay,” ibid., October 4, 1950: 30.

21 Ned Cronin, “Eddie Mayo: Blinked Out Blind Spot in Eye to Roar as Tiger,” Ibid., January 4, 1945: 17.

22 Tom Swope, “When Miller Makes Error, It’s News,” ibid., February 22,1945: 5.

Full Name

Edward Joseph Mayo

Born

April 15, 1910 at Holyoke, MA (USA)

Died

November 27, 2006 at Banning, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.