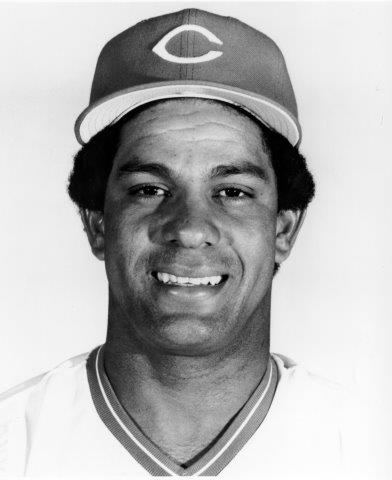

Mario Soto

With a population of just over 10 million, the Dominican Republic has produced approximately 450 big-league pitchers as of May 2021. Hall of Famers Juan Marichal and Pedro Martinez are easily the most famous, and most successful; however, no hurler from the Caribbean nation had a reputation as a harder thrower than Mario Soto.

With a population of just over 10 million, the Dominican Republic has produced approximately 450 big-league pitchers as of May 2021. Hall of Famers Juan Marichal and Pedro Martinez are easily the most famous, and most successful; however, no hurler from the Caribbean nation had a reputation as a harder thrower than Mario Soto.

A converted catcher, Soto caught on with the Cincinnati Reds on his fourth try, in 1977, and emerged over a six-year stretch (1980-1985) as one of the best right-handers in the majors, averaging 208 strikeouts per season while surrendering 6.8 hits per nine innings, the lowest of any starter active in those years.1 In his 12-year career, prematurely ended by arm and shoulder injuries, Soto (100-92) became just the third Dominican hurler to win at least 100 games, following Marichal and Joaquin Andujar.

Mario Melvin Soto was born on July 12, 1956, in Bani, the capital city of Peravia province, located on the south-central coast, about 35 miles southwest of the nation’s capital, Santo Domingo. When Soto was about 8 years old, his parents separated. His mother, Marta, raised Soto and his two siblings by working as a laundress. “We used to go down to the river at 6 in the morning, baskets of laundry on our heads,” recalled Soto of growing up with limited means, “and not come back until the evening.”2 Melvin, as Soto was called as a youth, quit school at the age of 14 and worked full-time in construction to help support the family.

Like many kids growing up in the baseball-crazed Dominican Republic, Soto idolized the country’s most accomplished player in the big leagues, Juan Marichal. Soto played baseball on local sandlots whenever he could, practicing in the evenings and playing games on Sundays. He started out as a catcher despite his tall and skinny stature, but had one flaw: “I couldn’t hit a lick.”3 Juan Melo, a longtime member of the Dominican national team, took note of Soto’s strong right arm and converted him to a pitcher at the age of 17. “I think [catching] helped me a little bit as far as pitching,” said Soto about his transition, which was easier than many expected. “I knew how the motion worked.”4 Soto immediately raised a few eyebrows with his bullets, but most major-league scouts combing the island for talent were uninterested in such an inexperienced hurler. One exception was Johnny Sierra, a bird-dog scout for the Cincinnati Reds. Sierra alerted team scout George Zuraw who traveled from the United States to check out the teenage Soto, who had been pitching for just two months. At a Reds tryout camp near Santo Domingo, Soto piqued Zuraw’s curiosity with his mechanics, delivery, and rhythm despite a fastball topping out in the low 80s and augmented by only a curveball. In late 1973 Soto accepted Zuraw’s offer of a $1,000 bonus and signed with the Reds. “Frankly, I wasn’t impressed,” said Zuraw years later, after Soto had become an All-Star with the Reds. “We signed him strictly on a projection basis. I’d be lying to you if I said I thought he would be great.”5

Soto’s transition to professional baseball in the United States was anything but smooth. Thrust into a country where he didn’t speak the language, know the customs, or have friends and family, Soto contemplated quitting and returning home on several occasions. To make matters worse, he broke his elbow at the Reds’ minor-league spring camp in 1974 and missed the entire season. In 1975, Soto was still plagued by arm pain and made only five appearances for the Eugene (Oregon) Emeralds in the Low-A Northwest League. Finally healthy in 1976, Soto discarded his curveball, which hurt his elbow, and rode his fastball, now in the low 90s, to a breakthrough season with the Tampa Tarpons, leading the Class-A Florida State League in ERA (1.87), innings (197), and strikeouts (124), while posting a 13-7 record. Mike Moore, general manager in Tampa, described Soto as “one of the best players ever to go through [the Reds’] organization.”6

The reigning two-time world champion Reds fast-tracked Soto to the big leagues, much to the pitcher’s detriment. He was added to the club’s 40-man roster after the 1976 season, and participated in his first big-league spring training in 1977. The Reds elevated the 20-year-old two levels, assigning him to Triple-A Indianapolis, where he was the fourth youngest hurler in the American Association. Facing mature players, many of whom had big-league experience, Soto blazed a trail, winning 11 of 16 decisions in 18 starts. When 37-year-old Reds starter Woody Fryman unexpectedly retired in early July to deplete an already thin staff, Soto was promoted. His debut on July 21 at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium was uninspiring; he yielded three hits and two runs in two innings of relief against the Pirates. Six days later, Soto tossed a complete game and struck out nine to win his first start, 6-2, against the Chicago Cubs. On August 7 he flashed his mid-90s heater to blank the Pirates, 9-0, leading skipper Sparky Anderson to gush, “Unless I’m totally crazy, the kid will be outstanding.”7 In that shutout, the first of 13 in his career, Soto also gave an inkling of the type pitcher he would become by knocking down Bill Robinson on consecutive brushback pitches in the first inning and letting one sail over the batter’s head in the sixth, precipitating a bench-clearing incident. A fatigued Soto (2-6, 5.34 ERA) pitched erratically thereafter and lost his next five decisions as the Big Red Machine finished in second place in the NL West.

Inconsistency, wildness, and injuries defined Soto’s next two seasons. He spent the 1978 campaign with Indianapolis, where he seemingly regressed (9-12, 5.01, 95 walks in 160 innings), followed by a brief September call-up. At the Reds spring training in 1979, he came down with severe back pain, necessitating hospitalization in late March. Back with Indianapolis to start the season, Soto was converted into a reliever and was recalled by the Reds in late June. His results for Cincinnati were disappointing: 30 walks and a 5.30 ERA in 37⅓ innings (25 appearances). Soto also made his one and only postseason appearance, tossing two scoreless innings against the Pittsburgh Pirates in Game Three in the NLCS. Soto’s status as a rising star was fading fast, as a quartet of 26-and-under right-handers had secured spots in the staff. Mike LaCoss won 14 games in 1979; 25-year-old Paul Moskau looked like a dependable starter, 21-year-old rookie Frank Pastore pitched well in the final two months of the season, and Tom Hume had been converted into one of the NL’s most dependable closers.

As he had after the previous four seasons, Soto joined the Leones del Escogido in the Dominican Winter League in 1979-80. He had spent the offseasons in Bani living with his mother, and seemed more relaxed and at ease pitching in Santo Domingo than in the United States. Hurling primarily out of the bullpen for manager Matty Alou, Soto posted a stellar 2.46 ERA in 80⅓ innings over 25 appearances. Nonetheless few predicted that Soto would translate that success to the Reds in 1980.

Cincinnati sportswriter Peter King suggested that if a film had been made about Soto’s 1980 campaign, it would be called “The Maturation of Mario Soto”;8 while Ray Buck of the Cincinnati Enquirer described Soto as the “sleeper of the staff.”9 Indeed, Soto’s midseason transformation from a meddling reliever, mop-up artist, and target of jeering fans’ anger and frustration to one of the most effective swingmen in baseball was stunning. The turning point came on July 5 when skipper John McNamara called on Soto (4.92 ERA at the time) to replace starter Bruce Berenyi, who had been knocked out after yielding six runs in one-third of an inning to the Houston Astros. Soto yielded three hits over 8⅔ scoreless innings, including setting down 16 batters in a row, to pick up his first victory in 10 months, 8-6. In his next outing, six days later, Soto was informed by McNamara just minutes before the game that he’d be starting in place of Frank Pastore. Soto tossed 130 pitches, scattering five hits over 8⅔ innings to pick up a 5-3 victory against the Atlanta Braves. He struck out 10 batters, the first of 27 times in his career that he whiffed 10 or more in a game.

Sportswriter Buck noted that the most difficult aspect for Soto was adjusting to the role of never knowing when he’d pitch, either as a starter or reliever.10 Reds pitching coach Bill Fischer was unequivocal in his praise of Soto, calling him “probably the best pitcher in the National League from July on.”11 Over the last six weeks of the campaign (beginning on August 13), Soto was “awesome,” according to teammate Johnny Bench.12 Soto seemed unhittable during that stretch, yielding just 35 hits (.147 batting average) and 11 earned runs (1.41) ERA in 70⅓ innings. Included were an overpowering complete-game 7-1 victory over the Braves on September 9 with a career-best 15 punchouts (one off the nine-inning team record set by Noodles Hahn in 1901 and tied by Jim Maloney in 1963; Maloney also fanned 18 in an 11-inning start in 1965) and a five-hit shutout against Houston in his next start. While Queen City sportswriter Lonnie Wheeler suggested that a strong case could be made for Soto as the team’s MVP instead of Ken Griffey, the lanky hurler settled for the Johnny Vander Meer Award, given by the Cincinnati chapter of the Baseball Writer Association of America to the team’s top hurler. It was well deserved as Soto (10-8, 3.07 ERA in 190⅓ innings) led the majors by allowing the fewest hits (6.0) and striking out the most batters (8.6) per nine innings.

Soto’s extraordinary emergence as one of the NL’s top hurlers can be directly attributed to his changeup, which players, coaches, sportswriters, and statisticians, including Bill James, considered not only one of the game’s best, but one of the best in history.13 “There’s no doubt that his changeup and his offspeed pitches with his fastball make him one of the best pitchers in all of baseball,” opined veteran Rusty Staub.14 Scott Breeden, the Reds’ minor-league roving pitcher instructor, is widely credited with teaching Soto the career-altering pitch. “Velocity is great, but movement on the ball is 90 percent of the battle,” said Ray Shore, a Reds scout. “[Soto] throws his changeup with perfect motion … but that thing drops right off the table. It’s almost like a spitter.”15

Soto relied essentially on two pitches, a fastball and changeup, throughout his career; he also occasionally showed a slider. His changeup, which was typically 10 to 15 mph slower than his mid-90s heater, froze batters and buckled their knees, leading to what sportswriter Tim Sullivan called “embarrassing” strikeouts.16 Bench once claimed that when Soto was in a groove and had command of both pitches, his fastball “looks like 120 [mph].”17 It was impossible for batters to tell Soto’s changeup and fastball apart when each left his hand. “I throw the changeup with the same motion that I throw the fastball,” said Soto.18 By 1980 he had enough trust in his changeup that it became his go-to pitch to either right- or left-handed hitters. “I get most of my strikeouts with the changeup,” said Soto bluntly.”That’s the pitch that’s made the difference for me.”19 Standing just 6 feet tall and weighing about 170 pounds, Soto might not have looked menacing like Bob Gibson and Don Drysdale, but he commanded the plate just as they did, and never shied away from throwing inside. Said batterymate Joe Nolan, “[Soto’s] just a little bit wild enough to keep batters from digging in.”20 All of those characteristics together made Soto one of the dominant strikeout pitchers in baseball. “If I had to build a pitching staff from scratch, I’d start with Soto,” said St. Louis Cardinals skipper Whitey Herzog, not known for hyperbole.21

Soto began the 1981 season widely hailed as the best pitcher from the Dominican Republic since Marichal. “We’re just going to turn him loose,” replied pitching coach Fischer when asked about his plans for Soto.22 Poor run support contributed to Soto’s rough start (1-5) despite pitching well. He won five of his next six decisions, each by complete game, punctuated by a stellar six-hit shutout with 12 punchouts against the New York Mets at Shea Stadium on June 10. Two days later the season was interrupted by the players’ strike, the fourth work stoppage in baseball since the players’ strike in 1972. When play resumed on August 9 with the All-Star Game, just over one-third of the season had been canceled. Soto picked up where had had left off, winning six of nine decisions. On the last day of the season, October 4, he spun a one-hit shutout against Atlanta at Riverfront Stadium with little motivation other than pride and honor. “Soto’s brilliance,” suggested beat writer Tim Sullivan, “was obscured by … the cloud of bitterness that hung over the Reds clubhouse.”23 Soto’s gem marked the Reds’ major-league-best 66th victory, but no one on the team rejoiced. Baseball owners had decided to split the season into two halves with the division winner in each half squaring off in a best-of-five playoff series. The Reds finished in second place in each half and were thus shut out of the playoffs. Prior to Soto’s performance the Reds salvaged some measure of dignity (and revenge) by unfurling a banner declaring “Baseball’s Best Record 1981.”24 Soto’s name was plastered among the NL leaders; he finished tied for third in wins (12), strikeouts (151), and innings (175), while tying for second in complete games (10) and first in starts (25). Soto and 36-year-old teammate Tom Seaver (14-2) formed the most potent one-two punch in baseball.

An aging Reds team hit rock bottom in 1982, setting a dubious franchise record with 101 losses. The NL’s worst team and the lowest-scoring club in the majors made pitching, and winning, a monumental task, all of which underscores Soto’s season as one of the best in Reds history. Named Opening Day starter for the first of five consecutive seasons, Soto displayed a performance that was an omen for what would unfold: He picked up the loss despite yielding just two runs in seven innings and fanning 10. Soto’s campaign reads like a highlight reel. He fanned 10 or more in a game nine times in 34 starts. On August 17 he equaled his career best with 15 punchouts, and did not issue a walk in a complete-game four-hit victory against the Mets.

Soto was durable, too. He went the distance 13 times; however, one of the best outings in his career, a 10-inning, three-hit, scoreless masterpiece, was good enough for just a no-decision in a 2-0 loss to Atlanta in 14 innings on June 27. Soto finished the season with a misleading 14-13 record, as the Reds scored two runs or less (18 total) in each of his losses. With a career-most 274 strikeouts, Soto broke Luis Tiant’s record for the most strikeouts in a season by a Latino player (264 in 1968) and eclipsed Maloney’s team record of 265 set in 1963. In a demonstration of control and power, Soto led the majors in strikeouts per nine innings (9.6), in the fewest hits/walks per inning (1.060) and in strikeout-to-walk ratio (3.86). Selected to his first of three consecutive All-Star Games, Soto tossed two scoreless innings, whiffing four. In the offseason he was named the Vander Meer winner by the BBWAA for the second time in three seasons.

Soto had a fiery and sometimes violent temperament on the mound. Despite his emergence as one of the best right-handers in baseball, he had a tendency to blow up after bad pitches, poor calls by umpires, hits, and runners on base. Recognizing Soto’s Achilles heel, opponents mercilessly bench-jockeyed him, further inflaming his rage. “[Soto] has the tendency to get mad and lose concentration, especially in close games,” said batterymate Alex Trevino.25 Hall of Famer Johnny Bench, who had caught his share of firebrands and loose cannons, such as Pedro Borbon and Ross Grimsley, tried to keep Soto level-headed and focused. “Sometimes he gets too fired up thinking of the strikeout title,” said Bench. “I try to get him to calm down. I say, ‘Stay back and figure out what you’re trying to do instead of starting to think in the middle of your windup.’”26 Soto’s temper got the best of him on May 31, 1982, against the Philadelphia Phillies at Veterans Stadium. He had yielded just one hit over six innings, but had also plunked two batters. When Phillies starter Ron Reed retaliated with Soto at bat in the seventh, an enraged Soto appeared as if he would sling the bat at the hurler, resulting in a benches-clearing brawl. Soto was ejected, but his reputation as a dirty player was cemented; however, Soto’s most publicized incidents were still two years off. His volatile on-field personality contrasted sharply with what Lonnie Wheeler of the Cincinnati Enquirer described as a soft-speaking, loner type persona away from the game.27

While Reds finished in the NL West cellar again in 1983, Soto fashioned yet another dominating season. Sportswriters noticed a change in his demeanor as the 26-year-old hurler won three of his first four starts despite a tender elbow in spring training and then blisters on his right fingers. “[M]aturity is his biggest asset now,” praised Lonnie Wheeler. He’s willing to handle some adversity.”28 In May, Soto went nine innings in each of his five starts, winning four of them by complete game, yielding just 22 hits (.148 batting average) and seven earned runs (1.40 ERA). “This is the best I’ve pitched over a long period,” said Soto, capping it off with a five-hit, 9-0 whitewashing of Pittsburgh. “[N]ot since the great double ‘play’ combo of Gilbert and Sullivan has anyone made the Pirates look so silly as Mario Soto,” wrote Sullivan ebulliently.29 On June 12 Soto flirted with a no-hitter, holding the Los Angeles Dodgers hitless for 6⅓ innings before Pedro Guerrero, his teammate with Escogido in winter ball, lined a single; Soto settled for a three-hitter.

Selected to start the All-Star Game at Comiskey Park in Chicago, Soto yielded two hits, two walks, and two unearned runs to pick up the loss. Days after he blanked Atlanta on three hits on September 13, the Reds announced that they had inked the hard-throwing righty to a five-year contract, widely reported to be the richest in Reds history at $6 million.30 The runner-up to Philadelphia’s John Denny for the Cy Young Award, Soto finished second in innings (273⅔) and strikeouts (242) to the Phillies ace Steve Carlton, and led the NL with 18 complete games, the most by a Reds hurler since Bob Purkey’s 18 in 1962. Soto was indeed the toast of town and the unequivocal center of Cincinnati’s baseball world. “He’s the kind of pitcher who intimidates hitters,” said Reds skipper Russ Nixon.31 A darling of the media, Soto pulled off a double at the annual BBWAA banquet in the Queen City, capturing his third Vander Meer award and the Ernie Lombardi Award as team MVP.

Buoyed by a multimillion-dollar contract, Soto jumped out of the gates in 1984, winning seven of his first eight decisions. On May 12 he was just one out from a no-hitter when George Hendrick of the St. Louis Cardinals spoiled it with a home run; Soto settled for a one-hitter as part of a career-best six straight winning starts. Everything changed for the emotional pitcher in a fateful start against Chicago at Wrigley Field on May 27, which Dave Parker of the Reds called “chaos and beyond.”32 Though Soto had shown signs of keeping his temper in check the previous season, he always appeared just a few bad calls away from a meltdown. In the bottom of the second, the Cubs’ Ron Cey belted a deep fly toward the left-field foul pole. Third-base umpire Steve Rippley ruled it a home run, beginning an ugly brouhaha that interrupted the game for 31 minutes.33 Soto immediately protested and had to be restrained by teammates. As the umpiring crew met to discuss the call, tempers on both sides simmered to a boiling point. About 20 minutes into the melee, Soto rushed into a scrum of players and coaches, heading for one of the umpires. At the last moment Reds catcher Brad Gulden tackled the outraged pitcher, hurling him into Cubs coach Don Zimmer; both benches simultaneously erupted into a nasty brawl. “If [Soto] had hit the umpire the way he was coming,” said Gulden, he probably wouldn’t play another game in his life.”34 When Soto was finally pulled away and led to the dugout, he was belted with ice from the stands. Soto went ballistic again, grabbed a bat, and attempted to climb into the box seats to confront the unruly spectator. Cey’s hit was ultimately ruled a foul, but the damage to Soto had been irrevocable.

When the NL suspended Soto for five days and fined him $1,000, it was the Cincinnati Enquirer’s turn to go ballistic. In a scathing editorial, the paper lambasted the penalty as “ridiculous” and harshly criticized Soto for his “intent on crude slugfest violence.”35 If Soto had a chance to redeem himself to the Cincinnati media and fans, it was lost three starts later, on June 16 in Atlanta, when he was inexplicably involved in another revolting incident that sportswriter Greg Hoard described as an “extraordinarily senseless act” and “out-and-out insanity.”36 The Braves’ Claudell Washington, already on edge from two brushback pitches from Soto earlier in the game, sent a not-so-subtle message when his bat opportunistically slid out of his hands and sailed toward the pitcher after a strike. Washington walked to the mound to confront Soto and a fight erupted.37 Soto’s inexcusable transgression occurred when the benches cleared. He violently tossed the baseball into the crowd on the mound; amazingly, no one was seriously injured. “When a pitcher fires the ball into the stack,” said home-plate umpire Lanny Harris after the game, “and hits an umpire and a coach, I think it is serious.”38 Soto was once again suspended for five days, and fined $5,000.

The two events marked a profound shift in the media’s portrayal of Soto, whose mental stability members of press openly questioned. Playing in a small market for mainly bad teams, Soto had undeservedly not gotten the national exposure he should have had. Now the national spotlight was on him, but for all of the wrong reasons. “I don’t care what they say about me,” said Soto unremorsefully. “Everybody is entitled to a few mistakes. Nobody is perfect.”39 Manager Vern Rapp defended his much-maligned hurler, and cautioned the media to consider Soto’s perspective. “I wish people knew where Mario comes from, how he had to fight to achieve what he has,” said the renowned player’s manager. “He still has to learn self-control, to act like a professional. Mario and I have sat down and talked about this. What he did this year had no malicious intent to it as far as I can see. I think he just became frightened, more than anything else. Somebody was trying to take away his livelihood.”40 Despite those words of encouragement, Soto retreated into a shell, finishing the season with a career-high 18 victories (seven losses) despite battling shoulder inflammation over the last six weeks of the season. He once again led the NL in complete games (13), but his ERA rose to 3.53 and his strikeouts dipped to 185 in 237⅓ innings.

Extremely sensitive to the fans’ and media’s criticism, Soto dug in during spring training. “If they’re going to hate me, they’re going to hate me,” he said.41 On the mound, Soto seemed to prosper in the four-man rotation ushered in by skipper Pete Rose and pitching coach Jim Kaat. He overcame some elbow tenderness and an altercation in an Atlanta nightclub to post an 8-3 record with a 2.48 ERA by June 4. Behind the scenes, it was a different story. “Yeah, I’m mad,” said Soto, directing his vehemence toward Rose and Kaat. “Why can’t I pitch on five days’ rest?”42 Claiming his fastball and changeup lost their effectiveness on less rest, Soto went into a tailspin beginning on June 9, losing eight straight decisions and 12 of his 16, while posting an uncharacteristically high 4.25 ERA. Equally noticeable to teammates and sportswriters was a profound change in Soto’s personality. “Somehow, some way, through a series of events and circumstances that only he knows,” opined beat writer Greg Hoard, “[Soto] has become withdrawn where he was once outgoing, and dispirited in performance, where he was formerly a vigorous competitor.”43 Soto took a me-against-the world posture, refusing any suggestion that he speak to the media about his slump. “When I pitch, this is my career,” he said defiantly.

“I have to handle it. I have to work it out myself. I don’t have to talk to anyone about it.”44 While the Reds unexpectedly challenged the Dodgers for the West crown, Soto missed several pivotal starts over the last five weeks of the season with toe and shoulder injuries. “There’s no reason to try [to pitch] when you’re not 100 percent,” he said.45 Sportswriters took Soto’s attitude for insouciance, and continued to bash the ailing hurler. “Soto’s legacy for the 1985 season,” wrote Hoard in an undeservedly scathing commentary, “will be that he and no one else lost the Western Division title for the Reds; that he lost heart, lost too many games.”46 Critics unfairly pointed to Soto’s losing record (12-15) as a sign of failure, while overlooking his durability (256⅔ innings) and strikeouts (214).

Soto’s ongoing battle with Cincinnati sportswriters continued to 1986. “[Y]ou just can’t keep going out there and have good years,” he said, trying to deflect incessant criticism, yet the comment only exacerbated the situation.47 Soto, a proud player who knew firsthand the personal sacrifice required to be a big leaguer, vowed not to speak to the press all season. By May 17, after his fifth consecutive loss, it was obvious that he was hurting, and not the same pitcher he was 12 months earlier. After he landed on the disabled list three times with shoulder pain, Soto’s career took another irreversible turn in late August when he underwent shoulder surgery by Dr. Frank Jobe in Los Angeles. Jobe diagnosed “erosion” in the pitcher’s wing, and not a rotator-cuff tear, but the damage to Soto proved to be permanent and career-altering.48 Soto (5-10, 4.71 ERA) missed the rest of the season.

Once one of the most overpowering pitchers in baseball, Soto was reduced to just 20 combined starts over the next two seasons. His velocity was noticeably down in 1987, and he spent much of season on the DL. After an unexpectedly productive spring training in 1988, Soto was tabbed by Rose to start his sixth Opening Day. He enjoyed a brief renaissance over the first six weeks, tossing a four-hit shutout against San Francisco in his second start and wining three of his first five decisions. With his last victory, a five-hitter against Chicago at Riverfront Stadium on May 20, Soto became the 17th Reds pitcher to notch 100 victories. Pain resurfaced in his shoulder thereafter, and he lost five straight starts, surrendering 34 hits and 21 earned runs in 23⅔ innings. On June 20, 1988, Cincinnati released him outright. Soto took offense to Rose’s disparaging remarks in the press, but otherwise saw the writing on the wall. A week later he signed as a free agent with the Los Angeles Dodgers. After just one outing with Bakersfield in the High-A California League, Soto was shelved for the remainder of the campaign.

Days after signing a minor-league contract with the Dodgers in December, Soto had second thoughts and announced his retirement. “I will definitely not recover,” he told El Caribe, a newspaper in Santo Domingo. “[I]t looks like my shoulder will not get better. I’ve already gone as far as I can go.”49 In parts of 12 seasons, Soto fashioned a 100-92 record with a 3.47 ERA in 1,730⅓ innings. His 1,449 strikeouts ranked second behind Maloney’s (1,592) as of 2020.

Since his retirement after the 1988 season, Soto has dedicated his life to helping young Dominican and Latino prospects realize their dream of making it to the big leagues. He organized a developmental baseball school near his hometown of Bani in 1991, and remained a staunch supporter of the Dominican Winter League, serving as GM of Leones del Escogides, a club he played on for 11 seasons.

In 2001 Soto was inducted into the Cincinnati Reds Hall of Fame, located in Great American Ball Park. He remained close to the Reds after his retirement, serving as a spring-training instructor, scout, and director of the team’s Dominican operations. In 2009 he was named a special assistant to the GM, and began working closely with Latino prospects in the Reds farm system, serving as a mentor, and helping them transition to a new country, language, and culture.

As of 2016, Soto still resided near Bani, in the Dominican Republic.

Last revised: October 29, 2022

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, and The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, and relied heavily on the Cincinnati Enquirer, accessed through newspapers.com. Special thanks to Bill Mortell for his assistance with genealogical research.

Notes

1 Nolan Ryan ranked second with 7.1 hits per nine innings. Dwight Gooden debuted in 1984 and surrendered 6.5 hits per nine innings over two seasons.

2 Steve Wulf, “His Bad Rap Is a Bad Rap,” Sports Illustrated, July 23, 1984. si.com/vault/1984/07/23/620158/his-bad-rep-is-a-bad-rap.

3 Tim Sullivan, “Some Changes Certain With Soto Pitching Today,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 5, 1982: D1.

4 Sullivan, “Some Changes Certain With Soto Pitching Today.”

5 Lonnie Wheeler, “The Changes in the ‘Two’ Lives of Soto,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 6, 1983: B1.

6 Jim Kaplan, “Soto Isn’t So-So Anymore,” Sports Illustrated, July 5, 1982. si.com/vault/1982/07/05/624641/soto-isnt-so-so-anymore

7 Bob Hertzell, “Reds Just Need a Few More Marios,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 8, 1977: 25.

8 Peter King, “Reds KO Braves Again as Soto Strikes Out 15,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 10, 1980: B1.

9 Ray Buck, “Magic-Man Soto Mystifies Dodgers, 6-5,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 18, 1980: B1.

10 Ray Buck, “Soto Cheered Not Jeered as Reds Rally to Whip Astros,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 6, 1981: C1.

11 Tim Sullivan, “Reds’ Plans for Soto Are Simple: Turn Him Loose,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 1, 1981: C1.

12 Peter King.

13 Bill James and Rob Neyer, Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers, (New York: Fireside, 2004), 35.

14 Peter King, “Soto Strikes Again! Marion Just Keeps Right On Whiffing,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 18, 1982: E1.

15 Tim Sullivan, “An Ace Isn’t an Ace When Soto Deals,” Cincinnati Enquirer, February 20, 1982: B1.

16 Tim Sullivan, “Soto Whiffs 11, Reds Zap Bucs,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 8, 1982: B1.

17 Peter King, “Reds KO Braves Again as Soto Strikes Out 15.”

18 Tim Sullivan, “Some Changes Certain With Soto Pitching Today.”

19 Tim Sullivan, “Soto Whiffs 11, Reds Zap Bucs.”

20 Tim Sullivan, “Soto Hurls Reds Past Mets, 2-0,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 11, 1981: B1.

21 Wulf.

22 Tim Sullivan, “Reds Plans for Soto Are Simple: Turn Him Loose.”

23 Tim Sullivan, “It’s Over and the Best Team Watches,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 5, 1981: D1.

24 Ed Reinke, AP Photo, Cincinnati Enquirer, October 5, 1981: D3.

25 Kaplan.

26 Kaplan.

27 Lonnie Wheeler, “The Changes in the ‘Two’ Lives of Soto.”

28 Wheeler.

29 Tim Sullivan, Soto Beats Bucs to Tune of 9-0,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 28, 1983: B1.

30 Wulf.

31 Lonnie Wheeler, “The Changes in the ‘Two’ Lives of Soto.”

32 Greg Hoard, ‘Suspension Looms for Soto After Brawl,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 28, 1984: D1.

33 A 33-minute clip of the entire melee can be found on You Tube. youtube.com/watch?v=qAhzFOBKrE8

34 Greg Hoard, ‘Suspension Looms for Soto After Brawl.”

35 “The National League Fell Short of Giving Soto What He Deserved,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 6, 1984: A16.

36 Greg Hoard, “Reds Will Appeal Soto’s Suspension This Time,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 21, 1984: B1.

37 The ruckus can be seen on You Tube. youtube.com/watch?v=bt0ftk6kFoA.

38 Lonnie Wheeler, “Reds Wind Up Winners, but Soto May be the Loser,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 17, 1984: C1.

39 “Soto Smiles Again With Giants Help,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 28, 1984: C8.

40 Wulf.

41 “Reds Notebook,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 5, 1985: B4.

42 Greg Hoard, “Soto Demands More Rest, Muddles Reds Pitching Scheme,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 16, 1985: D4.

43 Greg Hoard, “Soto Keeps His Troubles to Himself,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 30, 195: C1.

44 “Reds Notebook,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 22, 1985: B7.

45 “Reds Notebook,” Cincinnati Enquirer,” September 16, 1985: B5.

46 Greg Hoard, “Soto’s Certain He’ll Make a Comeback in 1986,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 8, 1985: D1.

47 Tim Sullivan, “Soto Embarks on a New Start,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 7, 1986: B4.

48 “Reds Notebook,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 24, 1986: C3.

49 Associated Press, “Shoulder Forces Soto to Retire,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 11, 1988: D1.

Full Name

Mario Melvin Soto

Born

July 12, 1956 at Bani, Peravia (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.