Rod Dedeaux

When Rod Dedeaux hit an RBI single in his first major-league start for the Brooklyn Dodgers in September 1935, it seemed a good omen for the beginning of a successful major-league career. Having graduated from the University of Southern California a few months earlier, he had been tapped by a struggling Dodgers organization as a prospect to watch. However, his hit was the only one of an abbreviated two-game major-league career.

When Rod Dedeaux hit an RBI single in his first major-league start for the Brooklyn Dodgers in September 1935, it seemed a good omen for the beginning of a successful major-league career. Having graduated from the University of Southern California a few months earlier, he had been tapped by a struggling Dodgers organization as a prospect to watch. However, his hit was the only one of an abbreviated two-game major-league career.

Dedeaux didn’t make a name for himself in the majors or even in minor-league baseball, but that wasn’t the end of his story in the sport. He became one of the most renowned college coaches of all time at his alma mater, where he set the standard for modern-day collegiate baseball programs across the country.

Raoul “Rod” Martial Dedeaux (pronounced DAY-doe) was born in New Orleans on February 17, 1914. His father, Henry Dedeaux, of French descent, migrated from the Mississippi Gulf Coast to New Orleans, where he married Valentine Boada. Rod was the youngest of their four children. Public records listed his father’s occupation as an inspector in the farming industry. The records show Dedeaux’s family moved to California between 1920 and 1930.1

Dedeaux attended middle school in Oakland before the family relocated to Southern California. He was an all-city selection in 1930 and 1931 at Hollywood High School and led the city league in hitting twice. He earned a bat signed by Babe Ruth for winning the Babe Ruth Slugging Award.2 While in high school, he developed a relationship with Casey Stengel, who made his offseason home in nearby Glendale while he was then managing at Toledo in the American Association. He frequently worked out at Hollywood’s Griffith Park under Stengel’s supervision and then went to Stengel’s home to discuss baseball.3 That initial relationship fostered additional connections between the two later in Dedeaux’s career.

Dedeaux attended the University of Southern California, where he was a three-year starter from 1933 to 1935 and was elected the team captain for his senior season.4 He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in education in 1935.5 On the recommendation of Stengel, the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Dedeaux to a contract.6

Dedeaux joined the Dodgers in early May before he had a chance to attend his graduation ceremony and participated in several workouts with the team. Stengel was impressed with his fielding in practice drills and said of his protégé, “I like to see ’em make that play (after Dedeaux snagged a groundball far to his right in a fielding drill). When a shortstop can do that, he can do anything.”7 Dedeaux’s initial minor-league assignment took him to Dayton of the Middle Atlantic League, where he hit well enough (.290) to earn a late-season call-up with the Dodgers. In Stengel’s second season as manager, the Dodgers finished in the second division (fifth place) for the second time. He decided to assemble a group of veteran and minor-league players in September in order to preview his candidates for the team the next season. Dedeaux was among the prospects Stengel wanted to assess.8

Dedeaux made his major-league debut on September 28 as a late-inning defensive replacement in a game at Ebbets Field that drew only 194 fans. He subbed for shortstop Lonny Frey, who had homered and doubled. Dedeaux didn’t get an at-bat in the Dodgers’ 12-2 blowout of the Philadelphia Phillies. He played the next day in the second game of a doubleheader against the Phillies, starting in place of Frey. He went 1-for-4 with an RBI single off Hal Kelleher in the seventh inning of a game that ended in a 4-4 tie after eight innings because of darkness. Those two games were Dedeaux’s only ones in the majors.

In 1936 Brooklyn initially optioned Dedeaux to its Allentown affiliate (New York-Penn League).9 However, he and the Dodgers could not agree on contract terms, and his option was transferred to Hazleton, a Phillies affiliate in the league.10 He played in 42 games before a back injury ended his season. He was out of baseball in 1937, but then returned for parts of the 1938 and 1939 seasons for several teams in the Western International League and Pacific Coast League. Dedeaux said of his abbreviated major-league career, “I had a cup of coffee but with no sugar. I think about it every day.”11

With his baseball career in jeopardy, Dedeaux founded the DART (Dedeaux Automotive Repair and Transit) trucking firm in 1938 with an investment of $500 from his signing bonus with Brooklyn.12 The company eventually became DART Entities and grew into a million-dollar trucking firm specializing in worldwide distribution. Even until his death, Dedeaux served as the company’s president and was involved in its daily activities.13

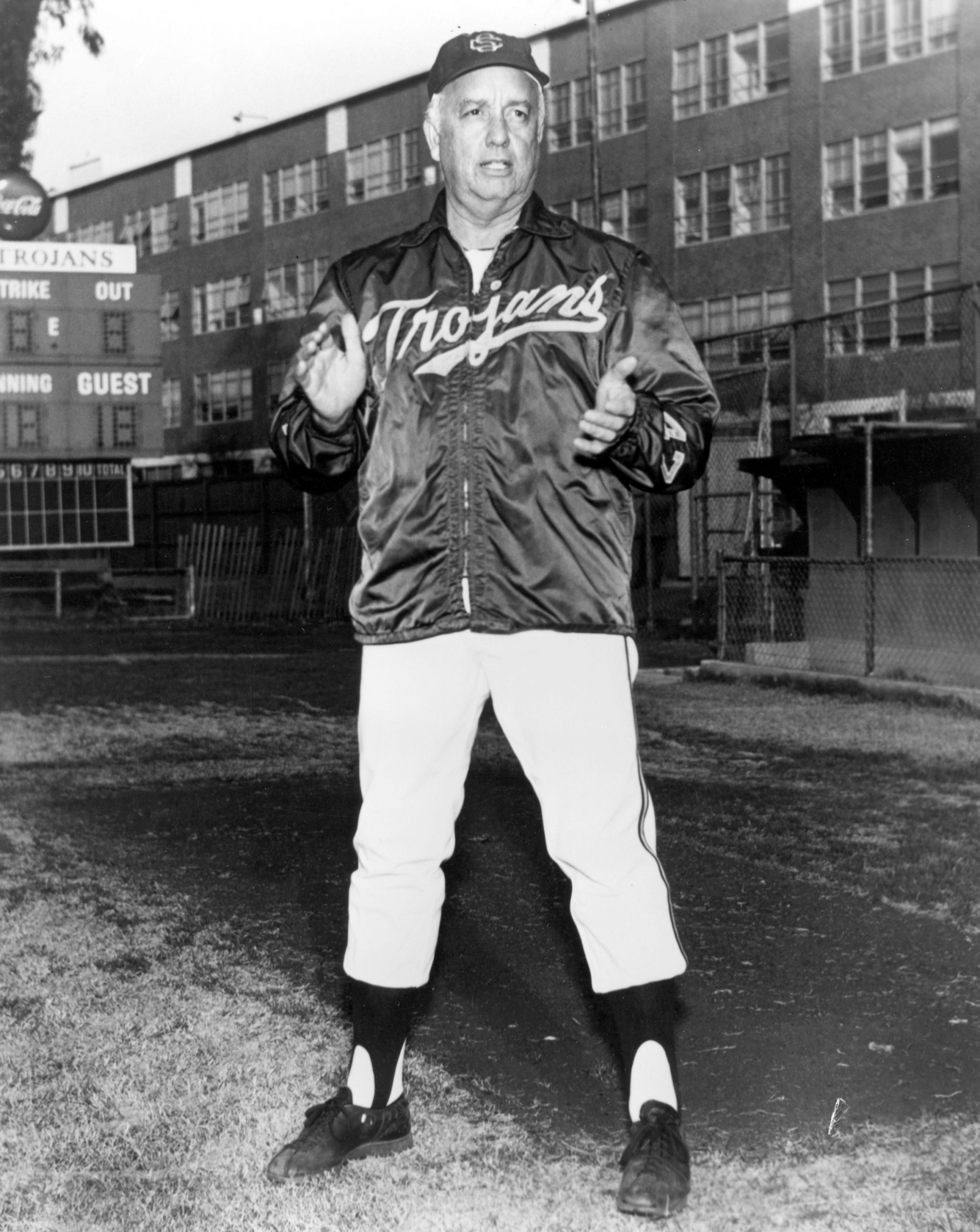

Rod Dedeaux during his playing days. (UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA)

But Dedeaux didn’t leave the sport entirely. He played for and coached semipro teams in the Los Angeles area, often competing in practice games against local colleges and military service-based teams.

USC lost several of its athletic department coaches to military service in 1942, and Dedeaux was named the interim head coach of baseball when head coach Sam Barry (who was also the head football and basketball coach) was assigned full-time duties in football during the spring.14 Then Barry was inducted into the Navy, and Dedeaux became the permanent coach. His first Trojans team won the California Intercollegiate championship in 1942.15 They finished second for the next three seasons. Dedeaux’s 65-year-old father died on the USC bench before the start of a Trojans game in 1943.16

When Barry returned from military service in 1946, they shared head coaching duties for the baseball program through the 1950 season. However, Dedeaux was the de facto head coach, as he was responsible for the major decisions for the team.17 In the College World Series in 1948, the Dedeaux-Barry coaching combination led USC over Yale in a best-of-three series for the first of 11 national titles under Dedeaux.

Another of Dedeaux’s connections with Stengel involved a 1951 preseason exhibition game on the USC campus between the Trojans and Stengel’s New York Yankees. Except for games played at West Point, the Yankees had never visited a college campus to play the home team. The Yankees had won the 1950 World Series, and the squad included Joe DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto, Yogi Berra, Johnny Mize, and Hank Bauer.18 The Yankees’ 15-1 victory included a mammoth home run by rookie Mickey Mantle that was measured years later by researchers to have been in the 650-foot range.19

Ten years after its first College World Series appearance, USC fought its way back from the losers bracket to defeat Missouri twice for the title. USC’s dominance continued with three CWS titles during the 1960s. Dedeaux’s Trojans captured a still unbroken record five consecutive championships from 1970 to 1974, including wins over other prominent national programs like Arizona State, Miami, and Florida State. In one of the most dramatic wins in College World Series history, the 1973 USC squad came from behind in the ninth inning to score eight runs and defeat Minnesota, 8-7. Gophers pitcher Dave Winfield had held the Trojans to one hit through eight innings. The 1978 team defeated Arizona State for the third time in the decade. As of 2020 Dedeaux still held the record with 11 College World Series championships as a coach.20

Dedeaux ended his 45-year tenure in 1986. His teams were 1,332-571-11 (.699), making him the then-winningest coach in collegiate baseball history.21

Dedeaux’s previous exposure to Stengel was evident in dealing with his Trojan players. He was known to clown around with them but found opportunities to mix in life’s lessons with his baseball teachings. Dedeaux said in a 1968 interview, “I have very definitely patterned my style after Casey’s. Thirty-odd years ago I figured he had the best brain in baseball. That was long before his success with the Yankees. I never had any trouble understanding Case.” Around USC, Dedeaux was sometimes called the Young Perfessor, a play on Stengel’s nickname the Old Perfessor.22

Dedeaux remained actively involved in his business during his coaching tenure at USC. During baseball season, he worked in the company’s office in the mornings and carried out his coaching duties in the afternoons. It was often joked that Dedeaux coached a baseball team in his spare time. After he retired, family members continued to operate the business.

He was responsible for building the USC program into a national power and helping to elevate college baseball across the country. Before Dedeaux developed his program at USC, major-league organizations didn’t look to collegiate baseball as a major source of amateur players. That changed with Dedeaux, who sent nearly 60 Trojans to the major leagues. Among the more successful players were Ron Fairly, Don Buford, Tom Seaver, Dave Kingman, Fred Lynn, Roy Smalley, Steve Kemp, Mark McGwire, Steve Busby, and Randy Johnson.23 Altogether, he sent nearly 200 players to professional baseball careers.

Los Angeles Times sports columnist Jim Murray called Dedeaux’s USC program, “the greatest farm club in the history of the major leagues,” adding, “[T]he most consistent supplier of major league talent the past 10 years is a franchise maintained at no cost to baseball. It finds and signs its own prospects, suits them up, develops them, refines them, weeds them out — and then turns them over to the big leagues fully polished and ready for the World Series.”24

The 1979 All-Star Game was indicative of Dedeaux’s influence in the majors. Four of his former players (Kemp, Kingman, Lynn, and Smalley) appeared in the game. An article in Collegiate Baseball Magazine quoted him, “I don’t believe any other school ever had that many all-stars in one game. I know it was one of the proudest moments of my life.” When asked what he attributed his program’s success to, he said, “First, you have to play smart baseball. … If you learn to do things right all the time, it doesn’t matter who you’re playing. Secondly, stay loose. When we work, we work hard; but we have fun, too. A little clowning always helps.”25

Dedeaux had opportunities to enter the major leagues as a coach or manager, but always chose to remain with his alma mater. Stengel was reported to have asked Dedeaux to take a coaching job with the Yankees so that he could be groomed to become his successor.26 Dedeaux did briefly hold a couple of jobs involving the majors, although not in the dugout. His Sporting News player contract card showed him as a scout for the Yankees in 1951, likely another result of his connection with Stengel. When the Brooklyn Dodgers relocated to California, they took advantage of Dedeaux’s popularity in the Los Angeles area by adding him to the Dodgers public-relations staff in 1958.27

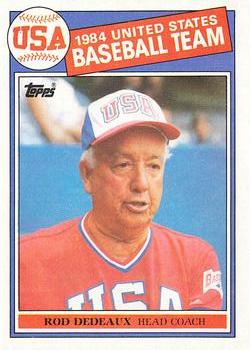

Dedeaux’s sphere of influence also extended to international baseball. He founded the USA-Japan Collegiate World Series in 1972 and was its chairman from 1972 to 1984. President Richard Nixon selected Dedeaux in 1974 to supervise a baseball clinic in Panama. He coached the US amateur team that played in Tokyo in conjunction with the 1964 Olympics. He was involved in bringing baseball to the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles as a demonstration sport and coached the U.S. team to a silver medal.28

Dedeaux’s sphere of influence also extended to international baseball. He founded the USA-Japan Collegiate World Series in 1972 and was its chairman from 1972 to 1984. President Richard Nixon selected Dedeaux in 1974 to supervise a baseball clinic in Panama. He coached the US amateur team that played in Tokyo in conjunction with the 1964 Olympics. He was involved in bringing baseball to the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles as a demonstration sport and coached the U.S. team to a silver medal.28

Among the many honors Dedeaux garnered during his career were Coach of the Century in 1999 by Baseball America and Collegiate Baseball. As part of the 50th anniversary of the College World Series in 1996, Dedeaux was named the head coach of the All-Time CWS team by a panel of former World Series coaches, media, and college baseball officials. He was named Coach of the Year six times by the American Baseball Coaches Association and was inducted into the organization’s Hall of Fame in 1970. 29

After retiring as head coach in 1986, Dedeaux took an administrative job as director of baseball at USC, where he advised athletic director Mike Garrett and head coach Mike Gillespie in the development of Trojan baseball. He also helped with fundraising activities for the program and worked as a spokesman for the sport at the collegiate and international levels.30

As chronicled in Robert Leach’s book about Dedeaux, Never Make the Same Mistake Once, Dedeaux’s accomplishments went far beyond a magnificent record as coach of a successful program. He was noted for his role in the development of his players into men, frequently using a set of maxims that had application on and off the field for his players.31

One of his more famous quips was “Some day there will be a pop fly that doesn’t come down.” It was his way of telling his players to always hustle down to first on a fly ball. It was also his way of instilling in his players a philosophy of never taking anything for granted in life.32

Marcel Lachemann attributed his major-league accomplishments as a player, coach, and manager to having played for Dedeaux. He said, “Rod was always an underlying influence. The number of things learned under Rod are very hard to single out, but if I had to pick one, it would be the ‘Never say die’ mentality that he instilled in all of us. We were never out of a game and thus produced some of the all-time come-from-behind victories ever seen.”33

Dedeaux’s son Justin had been a player for his father and was his assistant coach for several years. Rod wanted his son to replace him as head coach when he retired but ran into disagreement from the USC athletic director.34 His son Terry also played for USC.

Dedeaux was a fixture on the USC campus for 45 years and his legacy continued after he retired as the coach. The Trojan baseball field bears his name and a bronze statue of him ushers fans into the stadium. At the dedication of the statue in 2014, USC President C.L. Max Nikias said, “In the 134-year history of our university, very few people have had such a long and lasting impact on the University of Southern California community. Rod Dedeaux inspired our baseball players and enriched our campus spirit for more than half of the university’s history.”35

Dedeaux was married to Helen Louise Jones in 1940. In addition to Justin and Terry, their children included Denise and Michele. He died on January 5, 2006, at the age of 91.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Ancestry.com, and the following:

Glick, Shav. “Rod Dedeaux, 91; Led USC Teams to 11 National Baseball Championships,” Los Angeles Times, January 6, 2006.

Holmes, Tommy. “194 Pay Cash to See Dodgers Beat Phils, 12-2,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 29, 1935: D1.

Holmes, Tommy. “Casey Philosophizes: Dodgers Might Have Equaled Cubs’ Winning Streak in Longer Season,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 30, 1935: 18.

Hughes, Ed. “Raoul Dedeaux, New Dodger, Clever Fielder,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 3, 1935: 24.

Leach, Bob. “Never Make the Same Mistake Once: Remembering USC Baseball Coach Rod Dedeaux,” The National Pastime, 2011. sabr.org/research/never-make-same-mistake-once-remembering-usc-baseball-coach-rod-dedeaux. (accessed February 2, 2020).

Pietrusza, David, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman. Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia (New York: Total Sports Illustrated, 2000), 277.

Notes

1 Numerous sources about Dedeaux’s life omitted the exact year and reason for the family’s move to California.

2 David Rankin. Rod Dedeaux: Master of the Diamond (Monterey, California: Coaches Choice, 2013), 11.

3 Bill Becker, “Dedeaux Uses Stengel’s Style to Get Most Out of the USC Nine,” New York Times, June 23, 1968.

4 “Dedeaux Leads Trojan Nine,” Los Angeles Times, June 1, 1934: 2, 14.

5 “Trojans Lose Fifty-three Athletic Stars by Graduation Saturday,” Los Angeles Times, June 6, 1935: 2, 11.

6 Becker.

7 Tommy Holmes. “Cards’ Pilot on Sidelines, Feels Years,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 7, 1935: 14.

8 “Stengel Wavering on Youth Program,” The Sporting News, September 19, 1935: 2.

9 Howard W. Davis. “Pitching Is Big ‘If’ as NYP Loop Opens,” The Sporting News, April 30, 1936: 5.

10 Rankin, 14.

11 Rankin, 14.

12 DART Entities website. dartentities.com/about-us/our-history/ (accessed February 2, 2020).

13 2019 USC Baseball Record Book, s3.amazonaws.com/sidearm.sites/usctrojans.com/documents/2019/1/17/2019_record_book.pdf. (accessed February 2, 2020).

14 “Trojans Sign Shelby Calhoun,” Los Angeles Times, March 6, 1942: L, 19.

15 Paul Zimmerman, “Sport Postscripts, Los Angeles Times, May 1, 1942: L, 21.

16 “Dedeaux’s Dad Dies on Bench,” Los Angeles Times, April 24, 1943: 2, 8.

17 Rankin, 15.

18 Rankin, 18.

19 Robert McG. Thomas Jr. “Measuring a Blast,” New York Times, June 23, 1986: C2.

20 USC Baseball History & Archive. usctrojans.com/sports/2017/6/15/usc-baseball-archive.aspx. (accessed February 2, 2020).

21 Florida State University’s head coach Mike Martin retired in 2019 as the all-time winningest coach in NCAA baseball history with 2,029 victories. (https://seminoles.com/staff/mike-martin/).

22 Becker.

23 USC Baseball History & Archive.

24 2019 USC Baseball Record Book.

25 “Rod Dedeaux: A Coach for a Century,” USC News, February 1, 1999. news.usc.edu/9337/Rod-Dedeaux-A-Coach-For-the-Century/. (accessed February 2, 2020).

26 Mark Heisler. “Rod Dedeaux: Do You Measure This Man by Victories or Respect?” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 1986.

27 “Giles Loop Glint,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1958: 26.

28 2019 USC Baseball Record Book.

29 2019 USC Baseball Record Book.

30 “Rod Dedeaux: A Coach for a Century.”

31 Robert Leach, Never Make the Same Mistake Twice (Los Angeles: Figueroa Press, 2003), 12.

32 Leach, 69.

33 Leach, 104.

34 Heisler.

35 William Hanley, “Trojans Honor Former Coach Dedeaux,” Daily Trojan, February 18, 2014.

Full Name

Raoul Martial Dedeaux

Born

February 17, 1914 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

January 5, 2006 at Glendale, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.