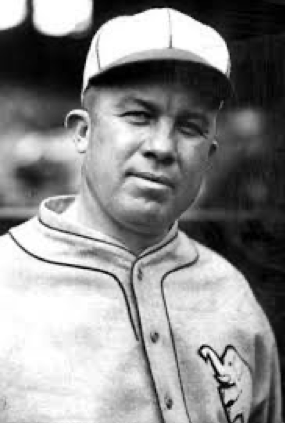

Joe Pate

Baseball has no player like Joe Pate today. He was a minor-league superstar, “the idol of Fort Worth baseball fans for a generation.”1 The burly left-handed pitcher won 257 games in 20 seasons from the bottom to the top of the minors. “Joe Pate was the greatest pitcher and put more money into the till than any other player in Texas League history,” said the circuit’s longtime president, J. Alvin Gardner.2 In 1972, he was inducted posthumously into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame.

Baseball has no player like Joe Pate today. He was a minor-league superstar, “the idol of Fort Worth baseball fans for a generation.”1 The burly left-handed pitcher won 257 games in 20 seasons from the bottom to the top of the minors. “Joe Pate was the greatest pitcher and put more money into the till than any other player in Texas League history,” said the circuit’s longtime president, J. Alvin Gardner.2 In 1972, he was inducted posthumously into the Texas Sports Hall of Fame.

His major-league stay lasted less than two years, but long enough to set a record for consecutive games pitched without a loss.

Pate was the ace of a Texas League dynasty. From 1920 through 1925 the Fort Worth Cats claimed six straight pennants and five Dixie Series against the Southern Association champions. Pate won at least 20 games every year and was the only pitcher in Texas League history to win 30 twice.

“Joe was what ball players call a pitcher—not just a thrower,” teammate Art Phelan wrote. “With every ball he pitched, he had an object in mind. … He didn’t have much of a curve ball, but he had perfect control of his fast and knuckle balls. He’s the only one I ever knew who could place his knuckle ball.” Umpire Larry Goetz said he threw a spitball, but two of his catchers denied that. “Pate didn’t need a spitter,” Ira Thomas said, because of his excellent knuckler.3

Joseph William Pate was born in Alice, Texas, on June 6, 1892, but he was always a year or two younger in “baseball age.” His parents, Mary (Edelbrock) and William Wesley Pate, moved the family to Fort Worth when Joe was three. He pitched and played quarterback at Central High and went on to Tulane University in New Orleans but quit school after two years to sign with Class-D Corpus Christi in 1911.

In six years, he had advanced to Class-A ball when World War I interrupted. He served with the Fifth Field Artillery, missing all of the 1917 season and most of 1918. Upon his return to civilian life, he signed with his hometown Fort Worth club of the Texas League, then in Class B. The team was officially named the Panthers but became known as Atz’s Cats after Jake Atz took over as manager in the ’teens, a job he held until 1929.

Pate’s run of excellence began in 1919, when he went 15-4 with a 2.10 ERA. From 1920 through 1925, while the Texas League moved up from Class B to Class A, and the Cats were winning five of six Dixie Series, Pate compiled a 153-63 mark and 2.80 ERA. He worked more than 300 innings every season and ranked among the leaders in strikeouts. He was 10-4 in Dixie Series play.

His pitching stablemate, right-handed spitballer Paul Wachtel, posted a 139-58 record in those six years. After the Texas League banned the spitter in 1921, Wachtel and other practitioners were allowed to keep using it for the rest of their careers. But the grandfather exemption didn’t apply to other leagues, so Wachtel couldn’t move up; he stayed in Fort Worth for 11 years.

The club’s offensive punch came from first baseman “Big Boy” Kraft, who slugged more than 30 homers in four straight seasons with a high of 55, the league record. The Cats won over 100 games in five out of six years.

Teammate Art Phelan described Pate as a control artist who worked slowly and took advantage of hitters’ impatience, “an absolute cake of ice on the pitching mound.”4 Another observer lampooned his “fidgety, delaying, annoysome [sic] tactics.”5

“Although he was a free-soul who reveled in the sheer fun of living,” writer Flem Hall commented, “the bull-shouldered pitcher was a fighter. He didn’t always snarl and kick and curse. Most of the time he only flattened out in a calm and businesslike manner and poured the poison with deadly effectiveness. Not infrequently though, he laughed as he fought from the sheer joy of the contest.”6

“They used to accuse Joe of cheating—of roughing the ball so he could control it better,” league President Gardner recalled. Pate said that was an act to get the hitters worrying about a scuffed ball. “Joe had very strong hands,” Gardner explained, “and could grip a ball so hard it would make the cover slip.”7 Pate stood 5-feet-10 with a listed weight of 184, but that was a fiction; he weighed in at 208 during the 1925 season and was often described as rotund.8

The good-natured hometown boy became Fort Worth’s biggest star. A large crowd was assured every time he took his turn on the mound. The local postmaster displayed a huge photo of Pate in the main post office, bigger than any “WANTED” poster. The powerhouse Cats and their ace lefty were the pride of Fort Worth, a small city fighting to shed its image as “Cowtown.”

While Pate appeared more than ready for the big time, he preferred to stay in Fort Worth. The club was paying him major-league money, about $7,000 a year.9 In addition, he had other business interests, including a store selling the latest technology: radios and batteries. He and his wife, Clara (Holden), had a young daughter, Mary Louise. He dodged the baseball draft with the connivance of several teams that helped the Cats skate around the rules.

Author Norman L. Macht documented several shady transactions in which Pate was sold to a major-league or higher minor-league club, but they were “phantom sales”—sham deals to allow Fort Worth to hang onto him.10 A sale to the Red Sox was voided because the pitcher “refused to report.” After Pate won 30 games for the first time in 1921, the Philadelphia Athletics drafted him, only to find out that the Toledo Mud Hens had already bought him. The San Antonio Evening News asked, “Was Joe Pate sold to Toledo to ‘cover him’ for Fort Worth team?”11 Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis answered “yes” and declared the transaction a fraud.

Pate contributed a legendary highlight to the Cats’ championship run. In Game Five of the 1923 Dixie Series against New Orleans, he was hit by a line drive that cut open his leg. Manager Atz announced that he was out for the rest of the Series, but Pate insisted he would pitch Game Seven “if I can stand.” He took the mound “on one leg” and limited the Pelicans to four hits in a 7-1 victory to clinch the championship.12

After the team won the 1924 Dixie Series, owner Amon Carter took Pate and Kraft to the big-league World Series in Washington and introduced them to President Coolidge. In the 1925 Dixie Series victory over Atlanta, Pate won his two starts, allowing only one run in 18 innings. That fall Connie Mack of the Athletics drafted him for real. Mack had seen Washington Senators owner Clark Griffith and manager Bucky Harris invent the relief ace with Fred Marberry and win back-to-back pennants in 1924 and 1925. He set his sights on Joe Pate to be his Marberry.

After drafting his man, Mack convinced him that the Athletics, long the American League doormats, were a team on the rise. With visions of a World Series dancing in his head and a contract for $7,500 tucked in his pocket (more than the A’s were paying young Lefty Grove), Pate agreed to join Philadelphia.13

The Athletics had bumbled through 10 straight losing seasons before they revived in 1925, buoyed by the additions of rookies Grove and catcher Mickey Cochrane plus second-year man Al Simmons, who hit .387. Seventeen-year-old Jimmie Foxx was serving an apprenticeship on the bench. Mack’s rebuilt club had spent more than half the season in first place before finishing second with an 88-64 record, and the Lean Leader was still spending money to forge a dynasty of his own that would win three straight pennants from 1929 to -1931.

Pate was 33 going on 34 when he reported for spring training in 1926, “the oldest rookie in captivity” (although some writers thought he was 31 or 32).14 Mack wanted a veteran in the key relief role, an experienced man who wouldn’t be spooked by pitching in clutch situations. He reportedly considered Guy Morton, 32, who had slipped down to A ball after 11 years with Cleveland, and Joe Martina, 36, who eventually won more than 300 games in the minors.15 Why he settled on Pate is unknown.

Mack wasted no time before testing his anointed relief ace with a game on the line. Pate made his debut in the season’s third game, against the defending AL champion Washington Senators. The A’s had taken a 4-0 lead, but starter Stan Baumgartner gave back three of those runs in the third inning. He left a mess: tying run on third, one out. Pate retired the side with the runner stranded.

After walking a batter, he went on to set down 14 straight before giving up his first hit in the eighth. While his teammates tacked on four more runs, Pate and his “shadowy curve” shut out the Senators for 6 2/3 innings to record his first big-league victory and Philadelphia’s first win of the season.16

Pate had relieved occasionally for Fort Worth, as was customary for starting pitchers in that era, but relievers were branded as second-rate. He still considered himself a starter and no doubt made his preference clear to his new boss. Mack gave him a start on May 6 against the St. Louis Browns. He lasted only three innings, giving up three runs. The Athletics came back to win in the ninth on Cochrane’s RBI single.

Four days later Pate got another start, again facing the Browns, after Philadelphia had won six in a row. This time he failed to survive the first inning. He loaded the bases and got his only out as a gift on a sacrifice bunt. Fred Heimach relieved and cleaned up Pate’s mess without allowing a run. The A’s hung on for their seventh straight victory.

That debacle ended Pate’s brief trial as a starting pitcher, but it began a stretch of 19 1/3 consecutive scoreless innings that lasted the rest of May and into June. During the streak, he came on in the second inning and shut out the White Sox for 7 1/3 frames to pick up his second win. He added another win and earned his first two saves (calculated years later) before he allowed a run.

He had established himself as the go-to late-inning reliever, but he was a finisher instead of a closer in the modern sense. Mack usually brought him in to pitch multiple innings in close games whether the A’s were ahead, tied, or behind. He pitched 45 times in relief and finished 33 of the games, working 109 2/3 innings with seven saves and just two blown saves. His 2.71 ERA (153 ERA+) was the best among major-league rookies in more than 100 innings.

On August 10 Mack summoned Pate in the ninth to protect a 3-2 lead over the White Sox, but he gave up a game-tying home run to Johnny Mostil. The Athletics bailed him out by rallying to win in 11 innings. The victory brought Pate’s record to 9-0. No one could recall any pitcher working so many games without being charged with a single loss all season.

“Pate doesn’t appear to have much stuff on the ball,” umpire and newspaper columnist Billy Evans wrote, “but his fast one has a little hop that makes the batters pop up, his change of pace is clever, and his knuckleball practically unhittable when he gets it over. But best of all Pate has nerve. He is what’s known in baseball as a ‘money pitcher,’ doing his best work when hardest pressed. The Athletics would have been lost without Pate this year. He is the 1926 model of Fred Marberry in the hero role.”17

Hero or not, Pate was unhappy with the role. The next spring, he held out briefly amid reports that he was pushing for a shot at the starting rotation. A rumor surfaced that he had threatened to quit unless he was sent back to Fort Worth. He denied that vehemently and was quoted as saying, “I don’t believe I ever heard of a major league pitcher who wanted to be shunted back to the minors.”18

After a talk with Mack, he signed his 1927 contract a couple of weeks late. The manager let him start two spring exhibition games. One was a disaster—four runs allowed in the first inning—while the other went okay. They were not auditions; Mack never wavered in his plan to use Pate out of the bullpen, but the distraction was unwelcome as the old man prepared to continue his pursuit of the Yankees, his pinstriped whale.

Fortifying his club for another pennant chase, Mack signed a pair of 40-year-old legends, Ty Cobb and Eddie Collins, and added a 39-year-old future Hall of Famer, Zack Wheat. After finishing third, just six games behind New York, manager Mack had high expectations for 1927. Owner Mack had to hope he was right, considering the money he was spending. Old and creaky as they were, Cobb, Collins, and Wheat didn’t work for Philly cheesesteaks. The Athletics’ payroll almost equaled that of the Yankees.

The season opened in just about the worst way possible. Philadelphia lost two at Yankee Stadium, with one tie. Pate relieved in all three games, and the last one was the beginning of the end of his time with the Athletics. They trailed by only 4-3 when Pate entered in the seventh to face the heart of the fearsome Yankee lineup. He walked Babe Ruth, then botched Lou Gehrig’s sacrifice bunt attempt for an error. A walk to Bob Meusel filled the bases. Tony Lazzeri’s single brought home two insurance runs that sealed the A’s defeat.

The club moved on to Washington and had built a 7-5 lead over the Senators when Pate relieved for the fourth straight day. He hit the first batter he faced, and after getting one out, gave up two singles to load the bases. Rube Walberg replaced him and let one of Pate’s runners score.

In those two appearances, Pate had retired one batter while allowing seven base runners and three runs (one unearned, but only because of his error). He didn’t pitch again for nearly three weeks. Mack complained publicly that he was out of shape. He returned for two appearances in May, then sat down for two more weeks. There was no report of any injury. Following his strong rookie season, Pate had been booted to the curb. Mack reportedly agreed to sell him to Shreveport of the Texas League but changed his mind.

Pate worked his way out of the manager’s doghouse. He gave up just one earned run in his first 13 1/3 innings in June and reclaimed the finisher role, registering three saves in four chances before the end of the month.

Pitching in his 71st major-league game on June 30, he still had not been charged with a loss, thanks to a lot of luck. His teammates had rallied to take him off the hook several times. That day in Washington, he blew a one-run lead and then gave up a walk-off RBI single to Goose Goslin in the bottom of the ninth to write “Losing Pitcher” next to his name in the box score. Later researchers confirmed that no pitcher had ever worked 70 consecutive games without a loss. The feat was more remarkable because it came in Pate’s first 70 games in the big leagues.

The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Jimmy Isaminger predicted that the record might stand as long as the pyramids. (It didn’t.) Noting that Pate had escaped defeat while often pitching in close games and inheriting runners on base, Isaminger concluded, his performance “proves his right to be called the rescuing king of baseball.”19

Isaminger’s awkward description of Pate’s role— “rescuing king” —points up the fact that the job didn’t have a name. It was a novelty to fans and sportswriters alike. Marberry had set a new standard in 1925 when he appeared in 55 games, all in relief. He topped that with 59 relief appearances the next year, but also started five games. Most pitchers did double duty, starting and relieving. Generally, only the weakest men on a staff were consigned to the bullpen. Even though starting pitchers completed less than half their games in the 1920s, few teams employed a relief ace, and the few who had the job didn’t want it because starters got the big paychecks. “Relieving,” late-inning specialist Ace Adams complained, “was the low dog.”20

Pate’s first loss came in his eighth appearance in 10 days. He seemed to be settling into a groove. In the first half of July, he recorded his fifth save but also was charged with another defeat. The five runs he allowed in the July 12 loss were unearned, but he was far from blameless. He was protecting a 3-2 lead over the White Sox with two out in the sixth inning when he loaded the bases on a single, a walk, and shortstop Joe Boley’s error. Then Pate surrendered two straight singles that brought in three runs to erase the lead. A fourth run scored when Pate threw wildly trying to stop a double steal. Neal Baker relieved him and allowed another of Pate’s runners to score. The A’s went on to lose, 8-5.

A week later, on July 19, Pate was charged with another loss, dropping his record to 0-3. Again, he had plenty of help. The Athletics took a 9-3 lead into the bottom of the ninth against the Tigers in Detroit. Then the wheels came off. Starter Walberg filled the bases with one out. Eddie Rommel relieved and immediately gave up a single and a triple to make the score 9-7. Mack brought in Pate to face Harry Heilmann, who was on his way to his fourth batting title. Heilman was a right-handed hitter; Mack replaced a right-handed pitcher with a lefty to face the most dangerous bat this side of Ruth and Gehrig. Heilman made him pay with an RBI double that cut Philadelphia’s lead to a single run. Pate recorded the second out, then walked two batters to load the bases again. Pinch-hitter Johnny Bassler delivered a two-run single to end the game and, as it turned out, end Pate’s major-league career.

After that demoralizing defeat, the A’s lost two out of three in Cleveland to fall 18 games behind the league-leading Yankees with more than two months remaining in the season. The next day Mack announced that he had released Joe Pate to Fort Worth. The manager gave no explanation. That left only speculation.

Jimmy Isaminger said the release was Pate’s choice. “Mack let him go when the southsider made it plain that he would like to go back to the Texas League,” Isaminger wrote, explaining that in Texas, “Pate is the ace-king of the baseball deck.”21

But conflicting stories emerged. According to one report, Mack had read the riot act to his players after the doubleheader loss in Cleveland, telling them that Pate wouldn’t be the only one packing his bags if they didn’t bear down. Another version said Pate had gotten into a dispute with Ty Cobb, who was a Mack favorite. Still another alleged that Mack had tired of Pate’s lax approach to conditioning.22

Pate himself said his release “came as a surprise,”23 a curious comment if it came at his request. Clearly, though, he had burned no bridges. “He left with everybody in Philadelphia wishing him the best of luck,” Isaminger wrote.24 And Pate never publicly acknowledged any problems with Mack or anyone else in Philadelphia, not even the notoriously abusive fans. “I can’t say anything against Connie,” he said the day after he was released. “He treated me squarely.”25 Still, he was happy to be going home. He sent a wire to a Fort Worth newspaper declaring, “Will say I am glad to get back where there are real folks.”26

He picked up where he had left off with the Cats almost two years earlier. For the rest of 1927, he pitched to a 2.07 ERA with a 6-3 record. But he had trouble readjusting to a starter’s workload and frequently needed help to finish games. When the problems carried over into the next season, Jake Atz began using him in relief. By August he was 11-8 with a 3.72 ERA.

With the Cats out of the pennant race, Atz loaned Pate to the Minneapolis Millers, who were very much in the race for the championship of the Double-A American Association. Pate agreed to go to Minneapolis, where he would be one step closer to the majors. The Millers wanted him as a reliever, and he gave them a boost down the stretch: a 1.50 ERA in 14 games. But the club fell short of the pennant.

Apparently still hoping for another shot at the majors, Pate agreed to stay with Minneapolis in 1929. At 37 he was strictly a junkman, “taking a world of time, making the batters fret and fooling them with twisters.” A Minneapolis writer said, “we are convinced he can and does do more things with a baseball than a monkey can do with a cocoanut.”27 The writer’s tongue may have been in his cheek, because it was in that year that umpire Larry Goetz said Pate was throwing a spitball, “one of the best.”28 In 52 games Pate posted an 11-5 record, but his ERA soared to 4.42 and the Millers released him at the end of the season.

He passed through five teams in the next three years, struggling to hang on. He was 40 when he finally conceded that he had nothing left and retired with a minor-league mark of 257-134. “You know, baseball was his whole life,” his wife, Clara, said later. “He was never the same after he stopped playing.”29 Pate stayed in the game for nine more years as an umpire, mostly in the Texas League.

His record streak without a loss stood for two decades. Cardinals right-hander Ted Wilks lost his last decision of 1945 and his first of 1948. For the two years in between, he went 12-0 in 77 appearances.30 The record has been broken many times since as relievers routinely began pitching only one inning or fractions of an inning.

After giving up umpiring, Pate owned a newsstand and domino parlor in downtown Fort Worth. A week before Christmas 1948, he came down with the flu, but insisted on going to work. When his wife begged him to stay home and call a doctor, he told her, “I’m like all old ball players. They never live much past 50 years. We give the best years of our lives playing ball and then we just seem to play out.” He shared Christmas dinner with Clara and died of a heart attack during the night.31 He was 56, but his obituary said 54.

Twenty years after he last played for the home team, Pate’s death was front-page news in Fort Worth. This sounds like a sportswriter’s fairy tale, but an eyewitness said it was true: As Pate’s casket was carried into the College Avenue Baptist Church for his funeral, two young boys stopped to watch. One said, “This is for Joe Pate, isn’t it?”

“Yeah,” his pal replied as they doffed their caps, “and my pop says he was the greatest pitcher ever in the Texas League.”32

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Bill Johnson.

Sources

Statistics from Baseball-Reference.com and The Minor League Register

Notes

1 “Joe Pate’s Funeral Plans Await Daughter’s Arrival,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 27, 1948: 1.

2 Associated Press, “Ex-Texas League Pitcher Is Dead,” Lubbock (Texas) Morning Avalanche, December 28, 1948: 4.

3 Goetz: Earl Lawson, “Goetz Scoffs at Roe’s Spitball Yarn,” The Sporting News, July 13, 1955: 4; Thomas: Don Donaghey, “Did Pate Use Spitter to Set Relief Mark for Rookie?” The Sporting News, July 13, 1955: 8. The Donaghey story said the spitball was legal when Pate was in the Texas League, but that is not so. The league outlawed the spitter in 1921, except for certain grandfathered pitchers. Pate was not one of them. William B. Ruggles, “Baseball Season to Open April 15,” Dallas Morning News, January 24, 1921: 3.

4 Art Phelan, “Never Met Anybody Who Disliked Joe Pate,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 27, 1948: 1.

5 Lorin McMullen, “Sports,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 27, 1948: 7.

6 Flem R. Hall, “The Sport Tide,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 27, 1948: 15.

7 Associated Press, “Ex-Texas League Pitcher Dead.”

8 Hall, “The Sport Tide,” March 11, 1926: 20.

9 Charles Johnson, “The Lowdown on Sports,” Minneapolis Star, March 30, 1929: Sports-3.

10 Norman L. Macht, Connie Mack, The Turbulent and Triumphant Years (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 404-406.

11 “Was Joe Pate sold to Toledo to ‘cover him’ for Fort Worth team?” San Antonio Evening News, November 2, 1921: 10.

12 “Telling How Cats Won Back Their Own,” The Sporting News, October 18, 1923: 5.

13 Macht, 406-407.

14 “Big League Highlights,” Hazelton (Pennsylvania) Plain Speaker, April 16, 1926: 18.

15 “The Old Sport’s Musings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 22, 1926: 12.

16 James C. Isaminger, “Macks Hand Rude Jolt to Senators,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 16, 1926: 24.

17 Billy Evans, “Pate of Athletics Becomes Champion Relief Hurler,” syndicated column in Pittsburgh Press, July 25, 1926: Sporting Section-3.

18 Elwood R. Rigby, “Rigby Says Cobb Will Get $55,000,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Record, March 9, 1927: 21.

19 Isaminger, “Pithy Tips from the Sports Ticker,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 3, 1927: 32.

20 Ace Adams interview by Brent Kelley, September 27, 1991, in the SABR Oral History Committee collection.

21 Isaminger, “Connie Could Use a Wee Bit of Luck,” The Sporting News, August 4, 1927: 3.

22 “Joe Pate Glad to Get Back to Fort Worth,” Fort Worth Record-Telegram, July 26, 1927: 13; McMullen, “Sports.”

23 “Joe Pate Glad.”

24 Isaminger, “Connie Could Use a Wee Bit of Luck.”

25 “Joe Pate Glad to Get Back to Fort Worth.”

26 “Telegram from Joe Pate,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram and Daily Record, July 31, 1927: 48.

27 Hall, “The Sport Tide,” September 7, 1928: 18.

28 Lawson.

29 Irvin Farman, “Joe Pate Dies at 54, Cat Pitching Great,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 27, 1948: 2.

30 Tom Ruane, “A Retro-Review of the 1940s,” Retrosheet.org, https://retrosheet.org/Research/RuaneT/rev1940_art.htm.

31 “Joe Pate’s Funeral Plans.”

32 “Teammates, Admirers Pay Graveside Tribute to Joe Pate,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 31, 1948: 2.

Full Name

Joseph William Pate

Born

June 6, 1892 at Alice, TX (USA)

Died

December 26, 1948 at Fort Worth, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.