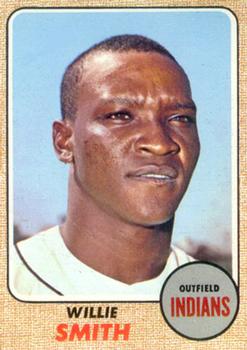

Willie Smith

Willie Smith is best remembered for his game-winning pinch-homer on Opening Day for the 1969 Chicago Cubs, but he surely deserves to be recalled for a much more enduring achievement: He was the last major leaguer — and the only African-American player ever — to have pitched and played different positions in the field in 15 or more games each in the same season.

Willie Smith is best remembered for his game-winning pinch-homer on Opening Day for the 1969 Chicago Cubs, but he surely deserves to be recalled for a much more enduring achievement: He was the last major leaguer — and the only African-American player ever — to have pitched and played different positions in the field in 15 or more games each in the same season.

Baseball is full of stories of players, mostly in the minors, who decided to try pitching rather than rely on their batting skills; Brooks Kieschnick among the most recent. Far fewer stopped pitching all together and made it as hitters; Rick Ankiel being the 21st century’s most successful convert. But you can count on your fingers the major leaguers who both pitched on a regular basis and frequently played other positions in the same season.

Obviously, the first who comes to mind is Babe Ruth, who in 1918 won 13 game on the mound and led the league in homers. Similar seasons are far more obscure: George Sisler‘s 1915 rookie year, Ray Caldwell’s 1918 or Johnny Cooney’s 1924, for instance.

Since World War II, however, just one player has had such a schizophrenic season: The left-handed pitcher-outfielder-first baseman from Anniston, Alabama: Wonderful Willie Smith. With the Los Angeles Angels in 1964, he hit .301 in 118 games, banging 11 homers. In 15 games over 31.2 innings as a pitcher, including a start, he had an earned run average of 2.84.

During his MLB career, Smith pitched in 29 games, starting three, threw 61 innings and compiled a 3.10 ERA. His switch to hitting clearly was not because he failed as a pitcher. Over parts of seven seasons in the minors, he was 49-27 with a 2.93 ERA — while compiling a .304 batting average in more than 1,200 plate appearances.

Smith grew up in the segregated South and first played professionally for the Birmingham Black Barons in the waning years of the Negro Leagues. He started the 1958 and 1959 East-West Negro American League all-star games at Chicago’s Comiskey Park.1 2 3

Willie Smith — he had no middle name — was born in Anniston on February 11, 1939. He was the youngest of four brothers and three sisters born to Tommie and Catherine Owens Smith. His parent separated when he was a child, and he was raised by his mother, who worked in a combination laundry-dry cleaner for a good decade to support the family. She died of complications from diabetes 10 days before the start of Smith’s 1963 season. 4 5

“I think my mom died just as much of hard work as diabetes,” Smith said in a 1964 interview with sports author Bill Libby for Baseball Digest. 6

Smith attended the segregated 12th Street School in Anniston for the primary grades and the all-black Calhoun County Training School in Hobson City, a section of Anniston, where he graduated in 1957. He was a star running back on the football team, but gave it up after breaking an arm. He recalled averaging about 17 points a game on the basketball team his senior year. His high school did not have a baseball team, but he played on local sandlot teams.7 Libby reported that Smith lost just twice pitching during his high school years, threw three no-hitters and hit over .400. Still, he apparently was not scouted. He boxed as a middleweight amateur in 10 bouts, winning eight, but having his nose broken three times put an end to that.8 9

Childhood friend Rendon Marbury of Leeds, Ala., said he often played against Smith, who began playing against adults before he reached high school and often was on the roster of at least three teams at a time.10 In the summer of 1957, Smith played on a local all-star team against the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. After a homer and two triples off Barons’ pitchers, he was offered a contract.11

The Barons’ players received a percentage of the ticket revenue, but by the late ’50s, the often barnstorming Negro League teams were not drawing large crowds. “If things were going good, we might make $200 a month. Many time, we’d play in the afternoon, get on the bus without showering, go on to the next town and play at night,” Smith told Libby.12

Anniston had its share of racial strife. In 1961, a bus that had carried members of the Congress of Racial Equality into town was burned by members of the Ku Klux Klan.13 Smith’s second wife, Dorothy “Dot” Smith, talking about her husband months after his death from a heart attack on January 16, 2006, said he faced the racism often directed at black players into the early ’60s during his first three years in the minors.

“He had to sit in the bus while other people got to go in and get their food. He said it made him more motivated to do what he wanted to do,” she said.14

Smith realized he was fortunate to get out of Anniston, a place where his brothers and his sisters’ husband all worked in the many metal-casting foundries in and around the town.

“If it weren’t for baseball, I’d be working with the others in a foundry today,” he told Libby.15

Smith did well enough for the Barons — pitching and playing the outfield and first base — that he attracted attention from scouts for the Chicago White Sox, Washington Senators, Cleveland Indians and Detroit Tigers.16 He was the starting pitcher on August 24, 1958, when the Negro American League’s all-stars played at Comiskey Park. Smith singled in the winning run.17 He also started the 1959 all-star game there and hit an inside-the-park homer.18

After his ’59 season with the Barons, Smith was signed by Detroit scouts Schoolboy Rowe and Jim Campbell (later the Tigers’ general manager). “The White Sox offered more money than Detroit, but the Tigers had a lot of older pitchers,” he said.”I thought my best shot at the majors was with Detroit. I got $1,500 for signing.”19

The Tigers sent Smith to Duluth-Superior in the Class C Northern League, where he was 10-6 with a 2.96 ERA in 1960. He pitched in just 20 of the 44 games in which he appeared, hitting .297 for the ’60 season. He spent the next two seasons at Knoxville, Tenn., in the South Atlantic League, where the pattern continued: He pitched in 55 games, with 23 wins, but appeared in 139 total, including pinch-hitting and playing in the outfield. He hit .272 in 1962.

Smith married the former Cleothus Elston of Anniston in April 1962, and the couple’s first child, Lester, was born later that year. Willie Jr. was born in 1964. A third son, Nicholas, was born in the early ‘70s before the couple divorced. Smith married his second wife, the former Dorothy Green, in 1977 and remained wedded to her until his death in 2006. He became the stepfather to three girls and two sons from her previous marriage.20

Smith was assigned to the Florida Instructional League in the fall of ’62, where he excelled against competition that included Pete Rose and Rico Petrocelli, among many future MLB stars. He compiled an 11-1 record with a 1.57 ERA and was named the league’s outstanding player.21

His manager in Florida, Phil Cavarretta, was among the first of many to comment on Smith’s affable personality. He’s “the kind of player who has the faculty of making friends and winning rooters,” Cavarretta told veteran sports writer Fred Lieb, who in turn described Smith as the player in the league with whom he was most impressed.22

Smith picked up the name “Wonderful Willie” in 1963, when he went 14-2 with Syracuse, the Tigers’ top farm club, and batted .380 (30 for 79). After his first eight victories (seven of them complete games), he was called up and made his major league debut on June 18, the day Charlie Dressen replaced Bob Scheffing as Detroit’s manager. Smith yielded a hit in two-thirds of an inning against the Boston Red Sox.23 On June 28, with the Tigers losing their 15th of 18 games, he was used a pinch hitter. He flied out. Two days later, June 30, he started for the Tigers against the Angels and pitched into the eighth inning. His first major league hit was an infield single. The Tigers won, 6-5, with a run in the bottom of the ninth.

Recalling his June 18 debut, “I walked out to the mound and …Carl Yastrzemski was coming to the plate. I almost lost my heart,” Smith said in 1990. After running the count to 3 and 1, “I managed to get a good curve over the outside corner, and he dribbled to second for the out.”24

On July 12, Smith entered the game as a pinch runner, then pitched a scoreless ninth to earn a save in the Tigers’ 7-6 victory over the White Sox. He won his only game of the year on July 19 with an inning of relief against the Angels. The next day, in an 11-2 Tigers loss, he pinch-hit for the second time, grounding out.

On July 23, in the first game of a twin bill, Smith made his second start. He failed to last three innings against the second-place White Sox. His ERA was over 5.00. He pinch-ran in the nightcap and again on the 25th. That was his last appearance with the Tigers until a September call-up.

Back at Syracuse, Smith was named the starting pitcher for the league’s all-star game against the defending champion New York Yankees. He blanked the Bombers over three innings, yielding no hits and one walk.25 Smith finished his two stints at Syracuse with a 2.11 ERA, best in the league by far, although he was seven innings short of qualifying as the official leader. Still, his winning percentage was tops in the league, and he was named the International League’s best pitcher for 1963.

After his recall, Smith earned his second save on September 23, fanning an aging Minnie Minoso with two runners on to preserve a 4-1 Tigers win over the Senators. He pitched two innings on September 25, lowering his ERA to 4.57. On the 28th, he made his final appearance of the season, scoring a run as a pinch runner. Early in his career, Smith was known for his foot speed. He had run the 100-yard dash in high school in 9.6 seconds.26

As the Tigers’ season ended, Dressen had high hopes for his young southpaw. “Smith should make the staff if he gets the hang of a new pitch in winter ball.”27 The suggestion didn’t go over well with Smith, however, although he did go with several Tigers prospects to play with Mayaguez in the Puerto Rican League.28

“Dressen was trying to get me to throw a slider,” Smith recalled in a 1990 interview. “I couldn’t get used to throwing it.” He said he thought this was a reason the Tigers traded him.29 Smith always conceded he didn’t have a great fastball. He threw curveballs about 75 percent of the time, with good control, mixing in the fastball and an occasional change-up.

“If I got a chance to pitch regularly in the big leagues, I’d be a pretty good pitcher,” he told Libby in 1964. “If I keep getting the chance, I’ll be a pretty good hitter here, too.”30

Despite his self-confidence, he was no braggart. He had been voted the most popular teammate three years in a row in the minors. His major league managers and teammates uniformly described him as a great clubhouse presence.

“It’s always good to have someone on the ball club who can keep the boys loose,” Smith told Jerome Holtzman during Willie’s time with the Cubs. “I’ve just been this type of fellow all my life. If some guy gets down in the dumps, I try to get him out of it, laughing, singing a few songs or cracking a few jokes.”31

But on-the-field performance keeps you in the majors, and by the spring of 1964, Smith found himself back in Syracuse. His break came April 28, when the Tigers traded him to the Angels for pitcher Julio Navarro.

“I remember he had a good swing,” Bill Rigney, Smith’s new manager, said. “But we didn’t get him for his bat.”32 The Angels were looking for bullpen help, which Smith provided immediately. In his first nine appearances, he fashioned an ERA of 1.80. His performance earned him a late-May start in which he yielded one earned run, departing with two outs in the sixth. It was the third time he pitched five innings or more.

On June 8, Rigney asked Smith to go to right field in the middle of a game. “I didn’t dare say I wouldn’t play out there,” Smith recalled in 1990. “The first ball that was hit in the inning was to me. I kept asking the Lord to let me catch the ball…. I made the catch, and I was okay after that.”33

In the bottom of the eighth, with the Angels leading the Indians 3-2, Rigney brought Smith in to pitch. With just the warm-ups from the mound, he yielded a two-run homer to Leon Wagner and a solo shot to Bob Chance.

“They used me as a relief pitcher. … I’m not one of these guys with a rubber arm who can throw seven or eight pitches and be ready,” he said in January 1970.34

Two nights before, he had given up two runs to the Yankees in the 15th inning after Dean Chance had thrown 14 scoreless frames. Those two outings put a damper on what had been until then a solid beginning as an Angels hurler. His last pitching stint came on June 15 in relief of Chance. It was uneventful. A week later, he was hitting cleanup.

In the nightcap of a June 14 doubleheader, Smith started in right field and hit his first big league homer. On June 23, he hit a two-run shot for a 2-0 victory over Washington. On June 24, he hit a three-run homer and a two-run triple. The Angels, meanwhile, went on an 11-game winning streak, with Smith responsible for key hits in five of those victories.

“Smith reminds me of Willie McCovey,” Rigney gushed. “He has the same quick wrists.”35

With the Angels in Boston during the left-handed-batting Smith’s hot streak, Ted Williams was watching on TV and jumped up when he first saw Willie. “Who is that batting?” he asked, according to a report by Angels beat writer Braven Dyer. Told it was Smith, the Splendid Splinter said, “Man, it’s been a long time since I’ve seen a swing like that. He’s really quick.”36

Smith finished 1964 hitting .301. All told, he had eight game-winning hits, four of them home runs. A free swinger, he drew just eight walks in 118 games, but he had 31 extra-base hits in 359 at-bats. That earned him a regular job as the Angels left fielder in 1965. He hit .261 with 14 homers in 498 plate appearances, but after the season, Rigney said he envisioned Smith as a bench player in 1966. With reduced playing time, Smith’s average fell to .185.37

Traded to the Indians, Smith was counted on as a backup first baseman and pinch hitter in ‘67, but after a slow start, he was sent to Portland, the Indians’ AAA farm team. There, he played much of the time at first base, but he pitched in five games, winning twice and striking out 12 batters in 12 innings. His earned run average was 0.75. At the plate, he belted 17 homers.

In 1968, Willie Smith finally got another chance to pitch in the majors. On June 1, with the Indians losing 5-2 to the Senators, Cleveland manager Alvin Dark sent Smith to the mound. He responded with two shutout innings. Three weeks later, on June 24, with the Tribe getting blown out by the Tigers, Smith pitched the last three innings, and again he didn’t allow a run.

Three days later, the Indians traded Smith to the Cubs. He pitched once for the Cubs, and again didn’t give up anything: two and two-thirds innings — no runs, hits or walks.

In 1969, Smith opened the season with the Cubs. In the season opener, on April 8 at Wrigley Field before a record crowd, they trailed the Phillies 6-5 with a man on in the bottom of the 11th when manager Leo Durocher called on Smith to pinch-hit. He homered into the right-field bleachers for the win. That put the Cubs in first place, where they would remain for 155 days.

“The man (Durocher) was kind of looking around between Al Spangler and me, and he kept shifting his eyes,” an unbylined Sporting News short quoted Smith as saying, “and finally he said, ‘Smitty, get a bat.”38 He almost didn’t make it to the plate. During a violent practice swing before coming up, he tweaked a muscle in his side. He paid a price for his heroics, too: A teammate spiked Smith’s foot during the celebration at home plate.39 In 2008, the Cubs’ web blog BleedCubbieBlue ranked Smith’s game-winner as the second most dramatic home run in Cubs’ history.40

On June 10, 1969, Smith hit another memorable home run. Pinch hitting in the top of the eighth against the Braves’ Ron Reed, he hit a 1-2 pitch into the upper deck of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. Just three other players later accomplished that same feat — Willie McCovey, Hank Aaron and Earl Williams.41 Teammate Ron Santo called it the hardest hit ball he had ever seen.42

With the Cubs, Smith was known, author Doug Feldmann wrote, as “easygoing, and everyone liked him. … He could always be heard humming a song or even making up his own lyrics to well-established tunes.” 43 Smith had been acquainted with Charley Pride, later to become a country music star, when Pride was playing for Memphis in the Negro American League and Smith was with Birmingham. Smith said he and other players used to make fun of Pride’s singing and guitar playing. Smith said he was shocked years later when he drove by a venue in Scottsdale, Arizona, and saw Pride’s name as the headliner.44

Smith was well aware of his own singing ability and said he actually considered professional crooning. He got a chance in July 1969. Along with teammate Nate Oliver, Smith shared lead vocals on “Pennant Fever,” a recording made by five Cubs, including Santo, Billy Williams and Gene Oliver. The inauspicious single didn’t keep the Cubs from losing the pennant to New York’s “Miracle Mets.”45

On May 12, 1970, Smith was in the Cubs’ bullpen when Ernie Banks hit his 500th home run. Braves outfielder Rico Carty retrieved the ball when it bounced out of the stands and tossed it to Smith, who ran it in to the Cubs’ dugout and presented it to Banks.46

After an offseason trade, Smith began 1971 with the Cincinnati Reds. He had nine hits in his first 30 at-bats, but he cooled off and was shipped to Indianapolis at the end of May.47 Although he tore up AAA pitching, hitting .467 in his first 137 at-bats and being named American Association player of the month for August, he knew he was unlikely to be recalled by the Reds.48 49

Again, he was called on to pitch, and threw three scoreless innings.

“I’ve sort of got it out of my system,” Smith said of his mound work. “But I still feel I could be a winning pitcher in the big leagues,” he told Dick Mittman for a Sporting News story.50

“Most of the guys coming down after seven years in the majors just don’t have to do it and won’t do it,” Smith said. “But since I’m down here, I might as well do my best.”51

That he did. After homering in the July 19 AAA all-star game, he went deep again in both ends of a doubleheader the next day. He finished the season at Indianapolis hitting .351, but nobody seemed to notice.

“Somebody, somewhere, I know I could help. If I continue to hit, somebody will want me.”52 It was not to be.

Promised more money than the Reds were offering,53 Smith decided to play in Japan in 1972, where he belted 24 homers for the Nankai Hawks. He pitched twice that season. He played for Nankai again in 1973, but regretted being so far from home.

Returning to Alabama, Smith made a few calls, hoping to get an offer from a major-league franchise. He chose not to go back to the minors, so his professional career was over. Living in Anniston, he was often called on by childhood friend Rudy Abbott, the longtime baseball coach at Jacksonville (Ala.) State University to help his players with their hitting.54 Like Abbott, Smith has a plaque in the Calhoun County (Ala,) Sports Hall of Fame, inducted posthumously in 2006.55 Smith worked in construction at nearby Fort McClellan before it was closed and at several jobs for the city of Oxford, Ala., near Anniston. He played for and coached a local semipro team, the Hobson City Tigers.56

Smith is buried in Maple Grove Cemetery on the outskirts of Anniston.

He never played in a World Series, despite being on one of Chicago’s best teams. “I wanted to do that,” he once said. “That’s the only thing I hate.”57

Smith clearly left an impression on the manager who almost got him to the World Series: Leo Durocher. In 1978, Jerome Holtzman recounted a story he said he was sure to be true: Late in a game, down by a run (in what would have to have been 1972), Leo barked, “Tell Willie Smith to get ready. I’m going to pinch-hit with him.” The bench fell silent. Eventually, veteran Jim Hickman got up and walked over to the manager, “and in a quiet voice said, ‘Skip, Willie Smith hasn’t been with us for the last two years, but if you want me to, I’ll find him and bring him here.’”58

“I love baseball,” Wonderful Willie Smith told the Anniston Star in 1977. “I sure do.”59

Sources

The three primary sources of material for this biography are:

Anniston (Ala.) Star, 1964-2016

Baseball Digest, September 1964

The Sporting News, 1958-1978

Smith’s MLB statistics are from Total Baseball and Baseball-Reference, which is also the source of most of his minor league statistics and the game accounts.

Notes

1 Willie’s Smith player page, minor/Negro/Japan statistics, www.baseballreference.com/register/player.cgi?id=smith-043wil Smith’s high school is misidentified, and Baseball-Reference lists Smith as a member of an independent black team in Cincinnati in 1946 and the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League in 1948. As he would have been 7 and 9 years old, this obviously must be another Willie Smith. Baseball-Reference makes no mention of his actual Negro American League playing career, 1957-59.

2 Cowens, Russ J., “East’s Four-Run Rally Decisive in NAL Star Game,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1958, 28.

3 Birmingham Black Barons rosters, www.bhamwiki.com (an encyclopedic resource about the Birmingham, Ala., region).

4 Libby, Bill, “The Amazing Transformation of Wonderful Willie Smith,” Baseball Digest, September 1964, 5.

5 Funeral notice, Anniston Star, January 21, 2006, 8.

6 Libby, “The Amazing Transformation…”

7 Pendergrass, James, “Willie Smith’s baseball career like movie script,” Anniston Star, July 8, 1990, 6B.

8 Libby, “The Amazing Transformation…”

9 Becker, Bill, “Willie Smith moves to the outfield; Angels move up,” The New York Times, June 28, 1964, 53.

10 Donovan, Rip, “A long trip to the Hall,” Anniston Star, June 17, 2006, 1C.

11 Libby, “The Amazing Transformation…”

12 Ibid.

13 www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1464 history of Anniston entry. There is no mention here of a disputed story, included in Libby’s Baseball Digest article, stating that segregationists burned down the Smith family’s house while Smith was playing for the Angels in 1964. Walter Winchell had written about it in his syndicated column, based an Associated Press account. According to a number of news stories in the Anniston Star, authorities found no evidence a fire that damaged the kitchen and garage of a vacant house adjacent to the Smith home was the result of arson. Smith’s wife said she had received no threats. The Smiths’ house was in what was described as “a colored neighborhood.” A U.S. Justice Department inquiry found no cause for the FBI to become involved.

14 Donovan, “A long trip to the Hall.”

15 Libby, “The Amazing Transformation…”

16 Ibid.

17 Cowens, “East’s Four-Run Rally Decisive .”

18 Sullivan, Floyd (ed.), Old Comiskey Park (McFarland Historic Ballpark Series, 2014).

19 Hester, Wayne, “Say Hey, Willie Smith!” Anniston Star, July 3, 1977, 1C.

20 Funeral notices for Smith, Anniston Star, January 21, 2006, 8, and for Joseph “Bo” Conley, father of Smith’s stepchildren, September 4, 2007, 5.

21 Lieb, Fred, “Tigers Hill Phenom Willie Smith Hailed as Loop’s No. 1 Gem,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1962, 32.

22 Ibid.

23 Reddy, Bill, “Willie Smith, Chief Hill and Bat Whiz, Wins Tiger Stripes,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1963, 27.

24 Pendergrass, “Willie Smith’s baseball career…”

25 Kritzer, Cy, “28,524 See I.L. Stars Halt Yankees on Two Hits,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1963.

26 Becker, “Willie Smith moves to the outfield…”

27 Spoelstra, Watson, “Tigers Concoct Southpaw Formula to Feed Yanks in ’64,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1963, 14.

28 “4 Tigers Accept Winter Bids,” (unbylined American League brief), The Sporting News, August 24, 1963, 29.

29 Pendergrass, “Willie Smith’s baseball career…”

30 Libby, “The Amazing Transformation…”

31 Holtzman, Jerome, “Willie Smith Loosens Up Cubs — ‘Like Dusty Rhodes, Says Leo,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1968, 16.

32 Dyer, Braven, “Angels Hide Willie’s Toeplate — Ex-Hurler Swinging a Potent Bat,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1964, 21.

33 Pendergrass, “Willie Smith’s baseball career…”

34 Plott, Bill, “Willie Likes Being a Cub,” Anniston Star, January 23, 1970, 1B.

35 Becker, “Willie Smith moves to the outfield…”

36 Dyer, Braven, “Smith, Piersall Triggermen for Angel Barrage,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1964, 21.

37 Newhan, Ross, “Walloping Willie Slated to Anchor Rig’s Thin Bench,” The Sporting News, January 8, 1966, 12.

38 “Leo makes right choice,” (unbylined National League brief) April 26, 1969, The Sporting News, 35.

39 Langford, George, “Record 40,796 See Cubs Win in 11th,” Chicago Tribune, April 9, 1969, Sports, 1.

40 Yellon, Al, “The Top 20 Cub HR of All Time,” www.bleedcubbieblue.com/2008/2/11/92853/7114

41 McCarter, Mark, “Smith feat noted at game,” Anniston Star, June 11, 1991, pg. 1B.

42 Donovan, “A Long Trip…”

43 Tutor, Phillip, “Wonderful Willie, our favorite Cub,” Anniston Star, October 28, 2016, 9 (quoting Feldmann, Doug, from Miracle Collapse: The 1969 Chicago Cubs (University of Nebraska Press, 2006).

44 Smith, George, “Anniston’s Willie Smith Can Still Swat ‘Em,” Anniston Star, March 10, 1974, 19.

45 Sullivan, Paul, “World Series shuffle: Unlike Bears, ’69 Cubs couldn’t back up boastful song,” Chicago Tribune, June 27, 2016 (www.chicagotribune.com/sports/baseball/cubs/ct-cubs-1969-pennant-fever-song-spt-0628-20160627-story.html)

46 Munzel, Edgar, “Banks, on 500th, Thought of Mom and Dad,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1970, 5.

47 Lawson, Earl, “Carbo’s Bat Dulled by Sophomore Jinx,” The Sporting News, May 8, 1971, 5.

48 Topps 12th Annual Minor League Player-of-the-Month Awards ad, The Sporting News, December 11, 1971, 45.

49 Mittman, Dick, “Indians Smith Providing Help With .467 Average,” The Sporting News, August 14, 1971, 37.

50 Ibid.

51 Ibid.

52 Ibid.

53 Hester, Wayne, “You Take Willie Smith,” Anniston Star, January 7, 1972, 8.

54 Strickland, Brad, “Former major-leaguer, Anniston native Willie Smith is dead at the age of 66,” Anniston Star, January 18, 2006, 1C.

55 Donovan, “A long trip…”

56 Strickland, “Former major-leaguer…”

57 Hester, “Say Hey…”

58 Holtzman, Jerome, “Kauffman to Revive the Royals’ Academy,” The Sporting News, July 1, 1978, 25.

59 Hester, “Say Hey…”

Full Name

Willie Smith

Born

February 11, 1939 at Anniston, AL (USA)

Died

January 16, 2006 at Anniston, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.