Yankee Stadium (New York)

This article was written by Vincent Cannato

In 1939, Yankee Stadium hosted the seventh All-Star Game between the American and National Leagues. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

The New York Yankees did not have an auspicious beginning as a franchise. Starting as the New York Highlanders, they played their home games at Hilltop Park in upper Manhattan from 1903 to 1912. In 1913 the Highlanders moved to the Polo Grounds and officially changed their name to the Yankees. (Before 1913, newspapers would often refer to the Highlanders with the nickname “Yankees” or “Yanks.”)1 The team played 10 uneasy seasons at the Polo Grounds, sharing the field with its owners, the New York Giants. From 1903 to 1915, the Highlanders/Yankees never won their division and had eight losing seasons.

In 1915 the Yankees were purchased by Jacob Ruppert, a beer magnate of German descent and a former congressman, and Tillinghast L’Hommedieu Huston, a wealthy engineer and contractor. They were determined to turn the Yankees into a winning franchise. To that end, they made two key decisions. First, they purchased the contract of Babe Ruth from the Red Sox in December 1919. Ruth had begun to revolutionize baseball by showing the possibilities of an offense geared toward the home run. In 1918, he led the league (with Tillie Walker) with 11 homers; in 1919 he led with 29 homers. In his first season with the Yankees, Ruth hit 54 home runs while playing his home games at the Polo Grounds.

With Ruth now a Yankee, Ruppert and Huston needed a new ballpark to showcase their star player. Attendance for Yankees home games more than doubled as the team began to outdraw the Giants, embarrassing the Giants owners, who made it clear that the Yankees should find a new home. That the Giants defeated the Yankees in both the 1921 and 1922 World Series did not lessen the fact that Babe Ruth proved a bigger attraction than the Giants.

Ruppert and Huston considered a number of locations for their new ballpark, including sites in Queens, the Inwood section at the northern tip of Manhattan, and 136th Street and Broadway in Manhattan. In the end, they settled on a 12½-acre lumber mill owned by the estate of William Waldorf Astor at 161st Street and River Avenue in the Bronx for which they paid $675,000. The site was directly across the Harlem River from the Polo Grounds. Ruppert and Huston relocated the franchise just as the population of the Bronx was exploding. Subway lines had begun to reach into the borough and with them came the building of apartments for the upwardly mobile middle class. The population of the Bronx increased from 200,507 in 1900 to 1,265,258 in 1930.2

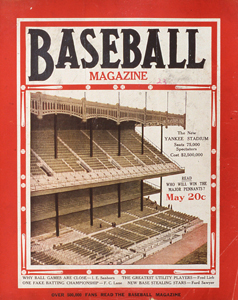

The groundbreaking for the new stadium took place in May 1922. The ballpark was completed in less than a year. The Osborn Engineering Company designed it. “Ruppert and Huston made it clear that they wanted Osborn to do something that went beyond all previous ballparks,” writes architectural historian Paul Goldberger. They wanted a stadium, not merely a ballpark, with a seating capacity bigger than any baseball venue in existence. Initially, the Osborn design called for a completely enclosed, circular stadium that would have looked like the multi-use ballparks of the 1970s. With decks completely surrounding the stadium, the plans called for a seating capacity of 80,000. In the end, the plans were modified and the upper decks ended at the flagpoles, allowing light and air to enter the stadium. The stadium cost the Yankee owners $2.5 million.3

The May 1923 issue of Baseball Magazine showed off the Yankees’ new $2.5 million stadium. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

White Construction Company was responsible for building the stadium, which required 30,000 cubic yards of concrete from Thomas Edison’s concrete company, 2,500 tons of structural steel, 2½ million feet of lumber shipped from the Pacific coast, and 16,000 square feet of sod. The signature of the new ballpark began as a minor detail: a copper frieze, which hung down 16 feet from the roof of the upper deck. Along with pinstripe uniforms, the frieze (later painted white) became an iconic symbol of the Yankees.4

Yankee Stadium was not the first to be called a “stadium” – Griffith Stadium in Washington was built in 1911 and Harvard Stadium in Boston was built in 1903 – but it was certainly the largest and grandest. It was the first triple-decker ballpark, consisting of field level, upper deck, and a 19-row mezzanine in between. There were, however, obstructed views caused by the upper-deck support beams.

Opening Day was a cool afternoon on Wednesday, April 18, 1923. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis took the subway to the game, and Governor Al Smith threw out the first ball. John Philip Sousa, the March King, and his band provided the pregame patriotic music. The papers estimated a crowd of 70,000 that day, but that was most likely an exaggeration, as the new park could hold only 60,000. Whatever the exact number, it was far and away the largest crowd ever to turn out for a baseball game. The Yankees defeated the Red Sox, 4-1, on Bob Shawkey’s three-hit complete-game win, but the day belonged to Babe Ruth. In the bottom of the third inning, with two runners on base, Ruth launched a home run into the right-field seats, the first home run in the new stadium. Sportswriter Fred Lieb dubbed the new stadium The House That Ruth Built. It was true in more ways than one, and the name stuck for more than eight decades.5

The stadium was built to accommodate the Yankees’ star slugger. Originally, the right- and left-field foul poles were 255 feet from home plate. From there, the outfield fences shot out to 423 feet in right-center and 474 in left-center with dead center 487 feet away. The deepest part of the ballfield came to be known as “Death Valley,” which began at 500 feet. The field benefited sluggers like Ruth who could hit the ball down the lines for a home run – although some argue that short foul poles cost Ruth homers, with umpires calling some of his shots foul. In fact, it could be argued that the dimensions of the Polo Grounds were better suited for Ruth.6

The stadium remained a work in progress. For its second season, the right- and left-field fences were moved back to 280 (left field) and 295 (right field) feet. This helped reduce the so-called “Bloody Angle” between the right-field foul line and bleachers, which caused many difficult bounces. Death Valley was brought in to 490 feet. In the 1930s the Yankees closed down even more of the vast outfield expanse by moving center field in to 449 feet and left-center to 461 feet. Before the 1928 season, the Yankees added second- and third-level decks from the left-field foul pole to the bleachers; in 1937 the same was done from the right-field foul line. The changes in the outfield seating originally increased the number of seats in the stadium to just over 67,000 in the late 1920s and 71,679 in the late 1930s.When chairs replaced concrete benches in the bleachers, stadium capacity was reduced back to 67,000 by the late 1940s.7

To cap off a successful first year in their new ballpark, the Yankees defeated their Manhattan rivals, the New York Giants, for their first World Series championship. Ruth hit 41 home runs that season and was named American League MVP. In the first six years at their new stadium, the Yankees, led by manager Miller Huggins, won four pennants and three World Series titles. In 1927 the Yankees won 110 games with the Murderers’ Row of Ruth, Gehrig, Tony Lazzeri, Earle Combs, and Bob Meusel, one of baseball’s greatest teams of all time. Attendance at Yankee Stadium averaged about a million fans a year until the Great Depression reduced those numbers somewhat. Between 1923 and 1964, the Yankees had only one losing season. The Yankees now had both a monumental new home and a successful franchise worthy of their new stadium.

The new stadium was not without its tragedies. On May 19, 1929, the Yankees had taken a 3-0 lead against the Red Sox on homers by Ruth and Gehrig. The game had begun in sunshine but a few innings later clouds rolled in and brought a light drizzle. By the bottom of the fifth inning, the skies opened and the stadium was deluged in a massive downpour. Thousands of fans in the right-field bleachers – nicknamed “Ruthville” because so many of his homers had landed there – tried to make it to the stadium exits. In the mad rush to avoid the rain, two people were trampled to death and 62 people, many of them youngsters, were injured.8

Even from its earliest years, the Yankees were tied to tradition, and that sometimes made them slow to innovate. The first night game at Yankee Stadium did not come until 1946, 11 years after the first night game in the majors. “The Yankees were even slow in holding Ladies Day for their female fans,” write Steve Steinberg and Lyle Spatz, with the first such event taking place in 1938.9 More importantly, the Yankees were slow to embrace racial integration. Not until 1955, eight years after Jackie Robinson broke the game’s color line, did the Yankees add their first African American, Elston Howard, to their roster.

Their slowness to integrate is ironic considering that the team had been welcoming Negro League games at the stadium for some time. The first Negro League game at Yankee Stadium took place on July 5, 1930, between the New York Lincoln Giants and Baltimore Black Sox. For the next two decades, Negro League teams regularly played games at Yankee Stadium. From 1940 to 1947, the New York Black Yankees called it home, but many other teams also used the stadium. From 1940 to 1946, a total of 145 Negro League games were played at Yankee Stadium, attracting 984,000 fans. For Negro League teams, playing games in Yankee Stadium meant prestige, large crowds, and, most importantly, bigger gate revenues, which helped keep those teams afloat.10

Ruppert died in 1939. Ed Barrow continued to run the team after Ruppert’s death, and Joe McCarthy continued as manager, having taken over in 1931. (McCarthy would continue as manager until he resigned during the 1947 season. Bucky Harris managed the Yankees in 1947-1948.) In 1945 Del Webb, Dan Topping, and Larry MacPhail purchased the Yankees from Ruppert’s estate for $2.8 million. (Webb and Topping bought out MacPhail two years later.) In 1947 George Weiss took over the operations of the team and in 1949 Casey Stengel became manager. In many ways, the postwar Yankees of Joe DiMaggio, Yogi Berra, Phil Rizzuto, Whitey Ford, and Vic Raschi were even more dominant than the prewar Yankees. From 1947 to 1964, the team reached the World Series in 15 out of 18 seasons, and won it 10 times.

Postwar exuberance brought attendance at the stadium to over 2 million, although, following larger trends, it dropped off in the 1950s. Even with that, attendance held steady throughout the 1950s and early 1960s, averaging about 1.5 million per season.

In 1953 Webb and Topping sold Yankee Stadium to Chicago businessman Arnold Johnson for $6.5 million. (Included in the deal was the Yankees’ minor-league stadium in Kansas City.) Johnson then turned around and sold the rights to the land below Yankee Stadium to the Knights of Columbus for $2.5 million. The Knights then leased the land back to the Yankees in a 28-year deal under which the team would pay the Knights $182,000 per year.11 When Johnson purchased the Philadelphia Athletics the following year, with plans to move the team to Kansas City, the commissioner’s office forced him to sell Yankee Stadium to avoid any conflict of interest. John Cox, a friend and business associate of Johnson’s, took ownership of the stadium and in 1962 would donate the stadium to his alma mater, Rice University – or at least it seemed that way. As was later discovered, Cox had only purchased an option to buy the stadium from Johnson, and did not actually own it. Therefore, as Jeff Katz writes, the “deed of gift from Cox to Rice was for his option to purchase stock, not outright stock.”12

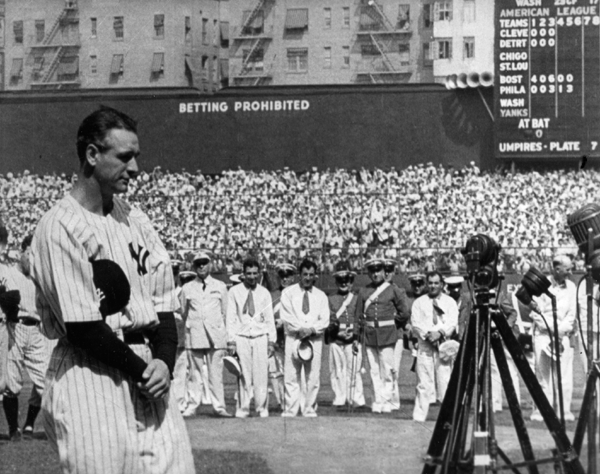

During the original Yankee Stadium’s first 42 years in operation, it witnessed 27 World Series (of which the Yanks won 20) and two All-Star Games (1939 and 1960). Some of the most iconic figures in baseball history called the stadium home. It was where Babe Ruth set the single-season home-run record of 60 in 1927 (breaking his own record of 59 set in 1921) and where Roger Maris broke Ruth’s record in 1961. It was where, on June 2, 1925, Lou Gehrig started at first base for Wally Pipp, the second game of his streak of 2,130 consecutive games. When Gehrig was too ill to play anymore, he bade farewell to fans on July 4, 1939, in one of the most memorable speeches in American history. Struggling with the effects of ALS, the disease that would kill him less than two years later at the age of 37, Gehrig called himself “the luckiest man on the face of the Earth.”13 The stadium also witnessed the only perfect game in World Series history when Don Larsen beat the Dodgers in Game Five of the 1956 World Series.

The Yankees also created what would become one of its greatest traditions. In 1947, the team held its first Old-Timers Day, featuring an exhibition game with retired players. Since then, it has been a way for the team and fans to honor those who once wore the pinstripes. Although other teams have held similar games, the Yankees are the only team to turn the event into a yearly celebration.

A packed crowd of 61,808 fans heard Lou Gehrig make his “Luckiest Man” speech between games of a doubleheader against Washington on July 4, 1939, at Yankee Stadium. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

Though baseball was the heart and soul of the stadium, it was never just an arena for the nation’s pastime. Fall and early winter meant football at Yankee Stadium. The football Giants called Yankee Stadium home from 1956 to 1973. It hosted three pre-Super Bowl NFL championship games, including one of the most famous football games ever played, the 1958 championship game between the Giants and the Baltimore Colts, when the Colts defeated the Giants in overtime on Alan Ameche’s one-yard touchdown run.14

College football also found a home at the stadium, most famously hosting 22 annual Army-Notre Dame games, which had been one of college football’s greatest rivalries. New York University and Fordham University also used Yankee Stadium as a home field. In the 1960s Eddie Robinson, the football coach at Grambling State University, persuaded Yankees officials to allow historically Black colleges to play a championship game each year at the stadium. Beginning in 1968, the New York Urban League Football Classic featured the best Black college football teams facing off at Yankee Stadium.15

Mid-century America’s other favorite sport was boxing. Over its 50-year history, the original stadium witnessed 29 title matches. Rocky Graziano, Sugar Ray Robinson, Rocky Marciano, and Floyd Patterson all fought to huge crowds in outdoor bouts. Perhaps the most famous fights at the Bronx ballpark were the two between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling. In 1936 the German fighter knocked out Louis in a victory that was celebrated in Nazi Germany. Two years later, Louis came back for a rematch and knocked out Schmeling, a victory widely celebrated in the African American community, helping turn Louis into a national hero.16

To see Yankee Stadium as purely a sports venue would be to miss another aspect of the monument’s social value. To many Americans, it was also a place of prayer and worship. In fact, the largest crowd in Yankee Stadium history did not occur during a sporting event, but rather at the Jehovah’s Witnesses Divine Will International Assembly on August 3, 1958. More than 122,000 people jammed into the stadium, filling both the stands and the outfield. Another 53,000 people assembled outside the stadium to listen on loudspeakers.17 The year before, evangelist Billy Graham had attracted over 100,000 people to the stadium, including Vice President Richard Nixon, for a religious revival as part of his long-running New York Crusade.18

The Catholic Church also had strong ties to the stadium. The highlight was Pope Paul VI’s visit on October 4, 1965, the first visit by a sitting pope to America. In addition to a speech at the United Nations and a visit to the Vatican Pavilion at the World’s Fair in Queens, the pope held a nighttime Mass for 90,000 worshippers at Yankee Stadium. The pope told the crowd, and the national audience tuned in to watch on television, “You must love peace.”19

As it entered its fifth decade of operation, Yankee Stadium had become one of the nation’s top sporting monuments. However, the stadium itself was starting to show wear. And so was the Bronx. And so were the Yankees.

***

It seemed appropriate that the great four-decade Yankee dynasty would end just as the City of New York was beginning its slow decline that ultimately led to its near-bankruptcy with the 1975 fiscal crisis. The year 1964 marked the Yankees’ last appearance in a World Series for the next 12 years. Attendance had already been declining. In 1961, 1.747 million had shown up to watch Mantle and Maris battle to beat Ruth’s home-run mark. Five years later, the last-place 1966 Yankees played before only 1.124 million fans.

In 1964 Dan Topping and Del Webb announced that they were selling the team to CBS. Corporate ownership was something new for the Yankees, but it was also a curious purchase for CBS. Buying the Yankees was CBS head Bill Paley’s attempt for status and prestige. “You certainly can’t expect to be the toast of such friends if you keep putting on … The Beverly Hillbillies,” an anonymous CBS executive explained. “On the other hand, if you own the Yankees … you’ve arrived.”20

CBS purchased the Yankees just as the team’s on-field performance was beginning to decline. To make matters worse, the Yankees fired a number of iconic figures, including manager Yogi Berra and announcer Mel Allen. In 1966 announcer Red Barber was told that his contract would not be renewed, allegedly after Barber insisted on pointing out the abysmally small crowd at a late September game in the Bronx. With a paid attendance of only 413, Barber called it the “smallest crowd in the history of Yankee Stadium,” noting that “the crowd is the story, not the game.”21

By the mid-1960s, the once great Yankees dynasty had fallen hard. Mediocre teams and an aging ballpark helped tamp down attendance, but there was another reason for the troubles at Yankee Stadium. Crime was skyrocketing in New York. In 1960 there were 435 murders in the city, and by 1965 that figure had climbed to 681. By 1970, the city suffered 1,201 murders. Burglaries, robberies, and car thefts all saw similar increases during those years.22

Legitimate fears of crime were mixed with the anxiety of White New Yorkers about the racial changes occurring in the Bronx. Although the population of both the city and the borough remained flat during the 1950s and 1960s, New York saw a flight to suburbia of middle-class Whites who were replaced in the city by a near equal number of lower-income African Americans and Puerto Ricans. The Bronx had been almost 90 percent White in 1950; by 1970 African Americans and Puerto Ricans made up 46 percent of the borough’s population.23

“There could be no denying that the Yankee Stadium neighborhood was changing,” wrote Marty Appel, former public-relations director for the Yankees.24 A symbol of the changes was the Grand Concourse, just three blocks east of Yankee Stadium. Long considered an elegant European-style boulevard, the Grand Concourse was beginning to fray by the mid-1960s. The Concourse Plaza Hotel at 161st Street, which for decades symbolized luxury and had once been home to many Yankees players, had by the late 1960s become a welfare hotel.25

In August 1970, at the annual Mayor’s Trophy Game between the Yankees and Mets, New York Mayor John Lindsay was seated with Mike Burke, who ran the Yankees for CBS. “Look, we’ve really got to do something for the Yankees,” Lindsay told Burke. “Will you come to a meeting next week at my office?” It was Lindsay who first approached the Yankees.26

Lindsay, whose mayoralty seemed to bounce from one crisis to another, did not want to see the Yankees leave New York. The New York football Giants officially announced their move to New Jersey in August 1971, as Lindsay and the Yankees were negotiating the deal over Yankee Stadium. Burke, for his part, happily responded to Lindsay’s offer by stating that the team’s preference was first for a domed, multipurpose stadium, in keeping with the style of new stadiums at the era. Barring that, the Yankees wanted a modernized stadium with improved parking and traffic flow to better accommodate its largely suburban fan base.27

In a letter to City Hall a few months later, Burke made clear the growing concerns about crime. “Given the apprehension about personal safety that grips all citizens, it becomes imperative that sports fans be able to drive private cars with relative ease directly to Yankee Stadium and to park within full sight and easy walking distance for it,” Burke wrote.28

Lindsay offered the Yankees a $24 million deal that would include the city acquiring both the land from the Knights of Columbus and the stadium from Rice University, as well as paying to renovate Yankee Stadium. The $24 million figure was what the city had spent a decade earlier to build Shea Stadium for the Mets.

In 1971 the city used the power of eminent domain to take both the stadium and the land on which it stood. It then proceeded to negotiate with Rice and the Knights for fair-value payment for their lost property. Meanwhile, the Yankees agreed to a 30-year lease with the city for the use of the new stadium.

Nobody believed that Lindsay’s $24 million offer was anywhere close to what the project would cost. In April 1973, Lindsay admitted that an additional $7 million would be needed for the project, but in private his budget chief was putting the total figure at closer to $80 million. Once Lindsay had made the deal to acquire the stadium and complete the renovations, the city was going to be on the hook for whatever the final bill was.29

The city’s generous offer was not enough to keep CBS interested in continuing its ownership of the team. Bill Paley had purchased the Yankees as a prestige project; now the Yankees had become more of an embarrassment. Paley quietly let it be known in the summer of 1972 that the team was for sale. Burke connected with a little-known Cleveland shipping executive, George Steinbrenner, and in January 1973 CBS announced that it had sold the Yankees to an ownership group headed by Steinbrenner for a cash deal of $10 million. CBS had bought the team for $13.2 million nine years earlier. While on paper it looked like an embarrassing loss for Paley and CBS, in reality with tax write-offs and depreciation, it turned out to be a wash.30

The last year in the old Yankee Stadium was 1973. The New York Giants, still waiting for their new Meadowlands stadium to be completed, played only their first two games of the 1973 season at Yankee Stadium before being forced to move to New Haven’s Yale Bowl.

The last game at the old ballpark was played on Sunday, September 30. More than 32,000 fans came out to see the Yankees lose to the Detroit Tigers for a disappointing cap to another mediocre season as the Yankees finished in fourth place with an 80-82 record. As soon as the last out was made, bedlam erupted as “fans set about taking Yankee Stadium home with them,” wrote Appel. “Those who didn’t storm the field for pieces of sod wiggled their seats loose from the concrete. …” At one point, first-base coach Elston Howard tussled with one of the unruly fans who was trying to grab first base out of Howard’s hands.31

The city wasted no time in continuing what those fans had begun on the last day of the season. The next day Lindsay was at Yankee Stadium for the groundbreaking of stadium renovations, which began with gutting the insides of the park. For the next two years, Shea Stadium was home until a new chapter at Yankee Stadium could be opened.

***

The Yankees returned to their newly renovated stadium on April 15, 1976, with an 11-4 victory over the Minnesota Twins before a sold-out crowd of 52,613. Bob Shawkey, the Yankees pitcher who won the first game at Yankee Stadium in 1923, threw out the first pitch. The Yankees held a pregame ceremony connecting the thread of the greatest memories from old park to the new park. DiMaggio, Mantle, Berra, Frank Gifford, and Joe Louis, as well as the widows of Ruth and Gehrig, were in attendance. Despite the Yankees’ win, it was Twins outfielder Dan Ford who hit the first home run in the renovated ballpark. (Newly named Yankee captain Thurman Munson became the first Yankee to homer in the ballpark, two days later.)32

By the time of the 1976 reopening, city officials were estimating that the stadium would end up costing the city at least $100 million, not including debt service, but they admitted that even that was not the final cost.33 The ultimate price tag for the Yankee Stadium renovations was never disclosed but estimated to be close to $150 million, almost six times Lindsay’s initial offer in 1971.

Whatever qualms there may have been about the public funding of the new ballpark, the newly renovated stadium was certainly an improvement. There was a 565-foot-long electronic scoreboard and escalators for the fans to reach the upper deck. There were no more obstructed views, since the old support posts were replaced by a cantilevered upper deck. There were fewer bleacher seats and the section of bleachers in dead center was blacked out so as not to distract batters. Not all of the changes were improvements. The famous frieze that lined the upper deck of the grandstand in the old ballpark was gone. All that remained was a replica frieze above the bleachers. Still, fans got more than 2,000 additional parking spots in a garage adjacent to the stadium, thus reducing the suburban fan’s exposure to the surrounding neighborhood. Blue plastic seats, a few inches wider than in the old stadium, replaced the old wooden seats. One of the most striking additions was a 138-foot smokestack in the shape of a baseball bat outside the main entrance to the stadium. Weighing 45 tons and made of stainless steel and fiberglass, the bat became a designated meeting place for fans.34

The renovated stadium held fewer seats than the old ballpark. Before the renovations, the stadium could hold 65,000 fans; the new ballpark held 57,145. The left-field foul line was moved out 11 feet to 312 feet, while the right-field line was moved out 14 feet, to 310 feet. The rest of the fences were moved in, including the infamous Death Valley. The deepest part of the ballpark in left-center field had once been 490 feet before being brought in to 461 feet in 1937. In the renovated ballpark, Death Valley now measured 417 feet (and would be moved in even closer to 408 feet in the late 1980s).35 In the old ballpark, Death Valley contained the monuments of Gehrig, Ruth, and Miller Huggins, which had stood in the field of play along with a flagpole. Now the monuments sat behind the outfield wall, paving the way for the creation of Monument Park. DiMaggio and Mantle received their own monuments there in the 1990s, with an additional 19 plaques going up between 1976 and 2008.36

The Yankees won three consecutive pennants and two World Series in their first three years in the new ballpark. A competitive team combined with a refurbished stadium with more parking in close proximity to the stadium helped draw more fans. Over 2 million people came to the Bronx ballpark in 1976, nearly double the crowds the Yankees drew in the old ballpark. By 1980, attendance had reached 2.6 million.

Despite the larger crowds, the situation in the Bronx had not improved. The borough lost 20 percent of its population during the 1970s. The South Bronx – the area immediately to the south of the stadium – was especially hit hard by waves of arson. During the 1970s, seven census tracts in the South Bronx lost more than 97 percent of their buildings to arson and abandonment; another 44 tracts had lost more than 50 percent of their buildings.37

This was brought home to baseball fans across the country on the night of October 12, 1977. It was Game Two of the World Series between the Dodgers and Yankees. Several times during the ABC telecast, cameras panned to a scene about a mile south of the stadium. A fiery blaze could be seen from the South Bronx – just one of the hundreds of fires that were decimating that section during the late 1960s and the 1970s. Announcers Howard Cosell and Keith Jackson discussed the fire at least five times during the game. Legend has it that Cosell said during the game: “Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning.” However, Cosell never actually said those words that night.38

Yet suburban fans were not deterred from coming to the Bronx to see baseball games. The question is what would happen when the Yankees stopped fielding competitive teams. The answer came during the 1980s and early 1990s. After the Yankees lost the 1981 World Series to the Dodgers, they failed to make the playoffs for the next 13 seasons. On top of that, crime continued to worsen during the crack epidemic of the late 1980s and early 1990s. Not surprisingly, attendance again tailed off, falling to 1.7 million by 1992.

Falling attendance at the stadium led Steinbrenner to make noises about taking his team elsewhere. A possible move to New Jersey was squashed in 1987 when that state’s voters rejected by a 2-to-1 vote a $185 million bond measure to pay for a new Yankee Stadium.

There was some debate about whether Steinbrenner would have actually moved the team from the Bronx. There was too much history there, and the Yankees were nothing if not tied to tradition. Although fears of relocating the team lingered throughout the late 1980s and the 1990s, the team’s changing fortunes in the mid-1990s quieted down such talk. After a 13-season drought, the Yankees finally made the playoffs in 1995, before losing to the Mariners in the Division Series. For 13 of the next 14 seasons, the Yankees made the playoffs, including winning the World Series in four out of five seasons from 1996 to 2000.

This mini-dynasty, led by the “Core Four” of Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Andy Pettitte, and Jorge Posada as well as skipper Joe Torre, helped revive the franchise. Just as the decline of the Yankees in the mid-1960s tracked the decline of New York City, the success of the late 1990s/early 2000s Yankee team mirrored the renaissance of New York City under the mayoralties of Rudy Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg. Crime and public disorder plummeted. The city no longer faced either looming bankruptcy or fiscal austerity and budget cuts. Between 1990 and 2010, the city’s population increased by more than 10 percent. The Bronx saw an even bigger increase in its population. These factors, plus the dominant Yankees teams of that era, brought more fans to the stadium. With 1.675 million fans in 1994, the stadium broke the 3 million mark in 2000 and the 4 million mark in 2005.

Despite all of this, Steinbrenner continued to make noises about moving his team out of the Bronx. In 1996 the architectural firm Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum (HOK) produced a study listing four possible alternative sites for a new Yankee Stadium: 1) Van Cortlandt Park in the northern Bronx; 2) Pelham Bay Park in the eastern Bronx; 3) the West Side Rail Yards along the Hudson River in Manhattan; and 4) its current site in the Bronx, either with a renovated stadium or a new stadium across the street. HOK strongly endorsed the West Side Rail Yard as the Yankees’ best option.39

The issue lay dormant for two years until April 13, 1998. A few hours before the Yankees were scheduled to play the Angels, a 500-pound concrete and steel beam fell and landed on Seat 7 in Section 22 of the loge level. No one was in the stadium at the time, but the games for that day and the following day were postponed. The fallen beam gave Steinbrenner ammunition to make his case for a new stadium.40

Steinbrenner was fortunate that Giuliani, who prided himself as the city’s number-one Yankees fan, was mayor of New York. The mayor became Steinbrenner’s key ally in finding the team a new stadium, keeping alive the idea of relocating the team to the West Side Rail Yards. Giuliani and Steinbrenner found little political support for a new stadium. Few believed that taxpayers should pay hundreds of millions of dollars to build a ballpark owned by wealthy private interests. The Yankees were also in the middle of what became one of the greatest seasons in franchise history in 1998. By the summer, perhaps recognizing the opposition to a new publicly funded stadium, Steinbrenner began to soften his stance. He opened up the possibility of the team paying some of the costs of a new stadium and said that if the city could guarantee 3 million fans per season, he would consider keeping the team in the Bronx.41

Giuliani had not given up on a dream of a new ballpark for the Yankees. Nothing more symbolized the close relationship between the Yankees and the Giuliani administration than when Deputy Mayor Randy Levine left his post at City Hall in 2000 to become president of the Yankees. In December 2001, a few days before he was set to leave office, Giuliani announced plans for two new stadiums, for both the Yankees and Mets. Both would have retractable domes. The stadiums were estimated to cost $1.6 billion each. The details of the financing were still not settled, but it was clear that the onus would fall on the city.42

Giuliani’s successor, billionaire businessman Michael Bloomberg, nixed the plan shortly after he took office, calling it “corporate welfare.” However, a few years later, a new stadium for the Yankees was back on the table. The city could either spend hundreds of millions of dollars to again renovate the stadium that it owned or it could find a way to get the Yankees a new stadium. In 2006 Bloomberg and state officials agreed on a plan for new stadiums for both the Yankees and Mets. Financing would come from a mix of city, state, and private funding. The new Yankee Stadium would be built across from the current stadium in Macombs Dam Park. Groundbreaking for the new stadium began in August 2006 and it was set to open in 2009.

The Yankees made 2008 a season-long celebration of the old ballpark. They drew a record 4.298 million fans that season, but the team missed the playoffs with a disappointing third-place 89-73 record. The final game took place on the night of September 21. An ailing 98-year-old Bob Sheppard, the Yankees’ public-address announcer for 57 years, recorded the starting lineup earlier that day from his home to be played before the game. The pregame ceremonies featured Yankees stars from previous decades. The Yankees defeated the Orioles that night, 7-3. Catcher José Molina hit the final home run at the Stadium.43

When the last out was completed, the fans did not run on the field as they did in 1973. (After the 1970s, increased stadium security, including the use of New York City police, had prevented fans from storming the playing field.) Instead, in 2008 most fans remained in their seats as the Yankees took the field one last time. Derek Jeter gave an impromptu speech thanking fans. “It’s a lot of tradition, a lot of history, a lot of memories,” Jeter said of the 85 seasons at Yankee Stadium. “Now the great thing about memories is you’re able to pass it along from generation to generation.” Jeter tipped his cap to the fans and then led his teammates for one final lap around the field as Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New York” played in the background.44

The refurbished, city-funded stadium had stood for 33 seasons from 1976 until 2008. During that time, it hosted 10 World Series (of which the Yankees won six) and two All-Star Games (1977 and 2008). This iteration of Yankee Stadium also had more than its share of baseball memories. In its first year, the stadium saw Chris Chambliss’s dramatic walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game Five of the ALCS against the Royals to send the Yankees to their first World Series in 12 years. As Chambliss rounded the bases, hundreds of jubilant fans took to the field, almost preventing Chambliss from reaching home plate.45

Another iconic game featured Reggie Jackson’s three home runs against the Dodgers in Game Six of the 1977 World Series.46 Dave Righetti threw a Fourth of July no-hitter against the Red Sox in 1983,47 and both David Wells and David Cone pitched perfect games, in 1998 and 1999 respectively. There were also controversies such as the 1983 “pine-tar incident,” when the Royals’ George Brett’s home run off Goose Gossage was called back because of excessive pine tar on Brett’s bat.48 Another controversy occurred during the first game of the 1996 ALCS against the Orioles, when 12-year-old Jeffrey Maier reached out with his glove to catch Derek Jeter’s fly ball to right field, yet the umpires ruled that Jeter had homered.

The renovated ballpark did not feature any NFL football, and the only college football was the Urban League Classic games between the best historically Black college football teams from 1976 to 1987. The renovated Yankee Stadium hosted, in 1976, the New York Cosmos soccer team, a team powered by superstars Pelé and Giorgio Chinaglia. (The old stadium had actually hosted the Cosmos in their inaugural season back in 1971.) Boxing also played less of a role, with the exception of the September 28, 1976, heavyweight fight between Muhammad Ali and Ken Norton when Ali successfully defended his title in a controversial 15-round decision.

Although Yankee Stadium appeared in a few movies, the small screen was perhaps the site of its most famous appearance. The popular 1990s sitcom Seinfeld contained a recurring storyline in which George Costanza worked for the Yankees as the assistant to the traveling secretary. The exterior of the stadium was often featured on the show, which also included an over-the-top rendition of George Steinbrenner voiced by creator Larry David.49

World leaders continue to pay visits to Yankee Stadium. John Paul II celebrated Mass for 80,000 worshippers on October 2, 1979, while his successor Benedict XVI would make it three papal visits to Yankee Stadium with a Mass on April 20, 2008. In June 1990 Nelson Mandela made the stadium the first stop on his American tour, just four months after being released from a South African prison. Wearing a Yankees cap and jacket, Mandela told the adoring crowd: “I am a Yankee.”50

Music was an integral part of Yankee Stadium. Concerts had been absent until the Beach Boys played in 1988. Beginning in 1980, Steinbrenner chose Frank Sinatra’s song “New York, New York” to be played over the loudspeakers after every home victory. Organ music was also an important part of Yankee games, with Eddie Layton playing the organ from 1967 to 2003. Robert Merrill, a longtime baritone for the Metropolitan Opera and a good friend of Steinbrenner’s, also became a fixture at Yankee Stadium starting in 1969. Wearing a Yankee pinstripe jersey with the number 1½, Merrill sang the National Anthem at Opening Day, Old-Timers Day, and other special occasions.

Apart from music, no other sound defined Yankee Stadium as the voice of Bob Sheppard, who served as the public-address announcer from 1951 to 2007. After Sheppard retired, Derek Jeter asked him to record the Yankees captain’s at-bat introduction to be used for every home at-bat. When the Yankees moved to their new ballpark in 2009, Paul Olden took over as the public-address announcer.

A large American flag is unfurled on the outfield by SUNY Maritime Academy cadets as the Yankees and Devil Rays are joined by members of the New York City Fire Department, EMS and Police Department during ceremonies honoring the victims of the World Trade Center terrorist attack. (MLB.com)

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, affected the entire nation, but especially New York City. Eleven days after the attacks, Giuliani asked Steinbrenner if the city could use the Stadium as the site of an interfaith memorial service called “Prayer for America.” Former President Bill Clinton, Oprah Winfrey, and singers Placido Domingo and Bette Midler were among the attendees.51 On October 30, 2001, at the start of Game Three of the World Series between the Yankees and Diamondbacks, President George W. Bush arrived to throw out the game’s first pitch. “What unnerved the fans was that they knew they were either in the safest place in the world at that moment or the absolutely most dangerous place in the world,” wrote Tom Verducci, “but they had no way of ruling out either choice with any certainty.” Wearing a blue FDNY jacket, Bush went to the pitcher’s mound and threw a perfect strike.52

In the wake of 9/11, all major-league ballparks began to play “God Bless America” during the seventh-inning stretch. Most stadiums dropped the tradition the following season, but it has continued at Yankee Stadium. For a number of years, the Irish tenor Ronan Tynan sang “God Bless America” in person until he was let go by the Yankees for making an anti-Semitic remark.53 The stadium also used a recorded version of Kate Smith’s rendition of the song, but that was ended in 2019 because of complaints that other Smith songs contained racist lyrics.54

***

Built across 161st Street from the original stadium, the new Yankee Stadium was an enormous structure, bigger than the old stadium, which was still standing on Opening Day and was not fully demolished until the following year. Whereas the renovated stadium had been painted white, the new stadium made from limestone, was a distinguished light brown. Tall, narrow, windowed arches wrapped around the exterior. Just inside the exterior shell of the new stadium was a seven-story, 31,000-square-foot grand concourse called the Great Hall lined with retail space and with 20 banners of Yankees greats hanging on the wall.

The final price tag for the new stadium was more than $1.5 billion. The Yankees financed their end of the deal from city- and state-backed bonds. Unlike many new stadiums, the Yankees never sold naming rights. The city and state spent $400 million on parking, parks, and improvements to the surrounding neighborhood. This included, for the first time, a Metro North train station for suburban commuters.

The south side of 161st Street, where the old stadium was located, was converted into a new, multi-use Macombs Dam Park, which includes four basketball courts, handball courts, and the Joseph Yancey Track and Field, with synthetic turf in the middle for football and soccer. The new park also includes three ballfields: one for baseball, one for softball, and one for Little League. The baseball field occupies the footprint of the old stadium field. In 2020 the field was named in honor of former Yankee Elston Howard.55

Luxury was the operative word for the new stadium. No expense was spared for the players’ clubhouse and training area. A high-end steakhouse was opened behind right field. High-definition video screens were everywhere. The new stadium had 56 luxury boxes. There were more than 4,000 premium field-level seats starting at $500 a ticket. The most expensive seats in the front rows cost $2,500 and included waiter service.56

However, not everything was perfect. The new stadium opened in the middle of a recession and the Yankees found it hard to sell all of their luxury boxes. Even worse, the front-row luxury seats were not filled for most games, with empty seats a common sight during televised games, forcing the team to cut the prices for all of their premium seats. There was another subtle difference between the ballparks. Verducci noticed that the new stadium was much quieter than the old one. The upper decks were sloped away from the field and did not feel on top of the ballfield as in the old stadium.57 Players noticed it as well. Jeter said that the new ballpark “had a different feel,” despite all the new amenities. The old stadium “was more intimidating,” he said. “The fans were right on top of you.” Mariano Rivera also complained that the new stadium “doesn’t hold noise, or home-team fervor, anywhere near the way the old place did.”58

Ruppert’s original Yankee Stadium was designed to make money by selling baseball to the burgeoning middle class. By contrast, the new Yankee Stadium, a sports venue geared increasingly toward the needs of the affluent, would become an emblem of a New York that Mayor Bloomberg once called a “luxury city.”

Ruppert’s Yankee Stadium was nothing if not grandiose, but it was also an original piece of architecture that the Yankees were able to fill with decades of memorable sporting and historical events. The Yankees have successfully transferred their 85 years of history – Monument Park, Old-Timers Day, Sinatra’s “New York, New York” – from the old ballpark to the new one. The question going forward is whether the new Yankee Stadium will be able to create traditions and memories of its own. If it does, then it too will become a national monument rather than a historical replica.

Notes

1 Marty Appel, Pinstripe Empire: The New York Yankees from Before the Babe to After the Boss (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012), 18-19.

2 Robert Weintraub, The House that Ruth Built (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2011), 23-32; Joseph Durso, Yankee Stadium: Fifty Years of Drama (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1972), 38-40; Paul Goldberger, Ballpark: Baseball in the American City (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020), 116-117; Neil J. Sullivan, The Diamond in the Bronx: Yankee Stadium and the Politics of New York (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 35-37; Steve Steinberg and Lyle Spatz, The Colonel and the Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 198.

3 Goldberger, 119-121.

4 Weintraub, 53-55.

5 Weintraub, 35-47; Appel, 130-132.

6 Philip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of All Major League and Negro League Ballparks, Fifth Edition (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2019), 213-214; Appel, 127; Weintraub, 91.

7 Lowry, 213-214.

8 “Two Dead, 62 Hurt in Yankee Stadium as Rain Stampedes Baseball Crowd,” New York Times, May 20, 1929: 1.

9 Steinberg and Spatz, 321.

10 For more on the Negro Leagues at Yankees Stadium, see Lawrence D. Hogan, “The Negro Leagues Discovered an Oasis at Yankee Stadium,” New York Times, February 13, 2011, and James Overmyer, “Black Baseball at Yankee Stadium: The House That Ruth Built and Satchel Furnished (with Fans),” in John Graf, Duke Goldman, and Larry Lester, eds., From Rube to Robinson: SABR’s Best Articles on Black Baseball (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2020), 59-76.

11 Christopher J. Kauffman, Faith and Fraternalism: The History of the Knights of Columbus Revised Edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992), 394.

12 Sullivan, 85-87; Jeff Katz, The Kansas City A’s & the Wrong Half of the Yankees (Hingham, Massachusetts: Maple Street Press, 2007), 158-159.

13 Ray Robinson and Christopher Jennison, Yankee Stadium: 75 Years of Drama, Glamor, and Glory (New York: Penguin Studio, 1998), 54-55.

14 Durso, 125-129.

15 Alfred Santasiere III, “Home of Champions, Part II,” MLB.com, November 1, 2013, https://www.mlb.com/news/yankee-stadium-college-football-history.

16 Durso, 90-94; “Memorable Fights at Yankee Stadium,” Sports Illustrated, October 20, 2010. https://www.si.com/boxing/2010/10/20/20-0memorable-fights-at-yankee-stadium#gid=ci0255c8fba00024a5&pid=yuri-foreman-vs-miguel-cotto.

17 “Jehovah’s Witnesses Rally 250,000 at Final Session,” New York Times, August 4, 1958: 1. Another 77,000 Jehovah’s Witness members gathered at the Polo Grounds at the same time, bringing the total at the two venues to over 250,000.

18 “100,000 Fill Yankee Stadium to Hear Graham,” New York Times, July 21, 1957: 1.

19 “Ninety Thousand Amens,” New York Times, October 5, 1965: SU2:1; Fourteen Hours: A Picture Story of the Pope’s Historic First Visit to America (New York: Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1965).

20 Sullivan, 124.

21 Barber quoted in Robinson and Jennison, 119.

22 Crime data comes from Kenneth T. Jackson, ed., The Encyclopedia of New York, Second Edition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 330.

23 Evelyn Gonzalez, The Bronx (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 110.

24 Appel, 360.

25 “Once-Grand Concourse: The Avenue, a Symbol of Prosperity Has Grown Old and Causes Concern,” New York Times, February 2, 1965: 35; “Grand Concourse: Hub of Bronx Is Undergoing Ethnic Change,” New York Times, July 21, 1966: 28; Young quoted in Tony Morante, “The Turbulent ’70s: Steinbrenner, the Stadium, and the 1970s Scene,” in Cecilia M. Tan, ed., The National Pastime: New York, New York: Baseball in the Big Apple (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2017), 111.

26 Sullivan, 117-119; Joseph Durso, “The $24-Million Picnic,” New York Times, April 5, 1971: 39.

27 Sullivan, 117.

28 Sullivan, 131-2.

29 “Memo Indicates City Obscured Stadium’s High Cost,” New York Times, February 3, 1976: 63.

30 Bill Madden, Steinbrenner: The Last Lion of Baseball (New York: HarperCollins, 2010), 9-13.

31 Appel, 394. The picture of Elston Howard and the fan fighting over first base can be found in New York Times, October 1, 1973: 50.

32 “Yankees Win First Game in Rebuilt Stadium,” New York Times, April 16, 1976: 57.

33 “Stadium’s Cost Now Seen as Loss,” New York Times, April 15, 1976: 69.

34 “Stadium’s New Big ‘Bat’ Proves a Hit in First Appearance Here,” New York Times, July 27, 1975: 34.

35 Lowry, 159-160.

36 Chris Landers, “The Long and Winding Story Behind Yankee Stadium’s Monument Park,” MLB.com, July 24, 2018, https://www.mlb.com/cut4/how-yankee-stadium-s-monument-park-was-created-c286873704.

37 Megan Roby, “The Push and Pull Dynamics of White Flight: A Study of the Bronx Between 1950 and 1980,” Bronx County Historical Society Journal, Vol. XLV, Nos. 1 & 2, Spring/Fall 2008, 34-55; Joe Flood, “Why the Bronx Burned,” New York Post, May 16, 2010, https://nypost.com/2010/05/16/why-the-bronx-burned/.

38 Jonathan Mahler, Ladies and Gentlemen, The Bronx Is Burning: 1977, Baseball, Politics, and the Battle for the Soul of the City (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), 330.

39 Sullivan, 165-166.

40 Murray Chass, “Beam May Be Lever for Steinbrenner’s Case,” New York Times, April 14, 1998: C1.

41 “As Gates Rise, Steinbrenner Softens on Bronx,” New York Times, July 9, 1998; “Steinbrenner Foes Buoyed by His Recent Comments, New York Times, July 10, 1998; “In First, Steinbrenner Offers to Help Pay for a New Stadium,” New York Times, July 29, 1998: B6; “Quit Whining and They Will Come,” New York Times, July 10, 1998: A14.

42 “In Bottom of the 9th, Giuliani Presents Deal on Stadiums,” New York Times, December 29, 2001: A1.

43 Appel, 552-556.

44 Appel, 556-7.

45 Joseph Wancho, “October 14, 1976: Chris Chambliss’ Home Run Delivers Pennant to the Bronx,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/october-14-1976-chris-chambliss-home-run-delivers-pennant-to-the-bronx/, accessed April 5, 2023.

46 Scott Ferkovich, “October 18, 1977: Reggie Becomes ‘Mr. October’ with 3 Home Runs in World Series,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/october-18-1977-reggie-becomes-mr-october-with-3-home-runs-in-world-series/, accessed April 5, 2023.

47 Bill Nowlin, “July 4, 1983: Dave Righetti Tosses a No-Hitter on Fourth of July,” SABR Games Project, https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/july-4-1983-dave-righetti-tosses-a-no-hitter-on-fourth-of-july/, accessed April 5, 2023.

48 Filip Bondy, The Pine Tar Game: The Kansas City Royals, the New York Yankees, and Baseball’s Most Absurd and Entertaining Controversy (New York: Scribner, 2015), 127-154.

49 Peter Botte, “How Larry David Turned His Yankees Pain into ‘Seinfeld’ Gold,” New York Post, April 11, 2020, https://nypost.com/2020/04/11/how-larry-david-turned-his-yankees-pain-into-seinfeld-gold/.

50 “Mandela Takes His Message to Rally in Yankee Stadium,” New York Times, June 22, 1990: A21.

51 Appel, 517.

52 Tom Verducci, “It’s Gone: The Passing of Baseball’s Cathedral,” Sports Illustrated, September 22, 2008, https://vault.si.com/vault/2008/09/22/its-gone-goodbye.

53 “Tenor Booted from Yankees Game after anti-Semitic Slur,” New York Post, October 16, 2009, https://nypost.com/2009/10/16/tenor-booted-from-yankees-game-after-anti-semitic-slur/.

54 “Yankees Drop Kate Smith’s ‘God Bless America’ After Being Told About Her Racist Songs,” USA Today, April 19, 2019, https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/yankees/2019/04/18/yankees-drop-kate-smith-god-bless-america-7th-inning-stretch/3510295002/.

55 New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, “Macombs Dam Park,” https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/macombs-dam-park/highlights/19804.

56 “Luxury Strikes Out,” Wall Street Journal, March 6, 2009: W1; “Red-Faced Yanks Cut Elite Prices,” New York Post, April 29, 2009: 5.

57 Verducci, “New Stadium an Instant Classic.”

58 Chris Smith, “Derek Jeter Opens the Door,” New York Magazine, September 21, 2014, https://nymag.com/intelligencer/2014/09/derek-jeter-private-photos.html; “Mo Rivera: Old Yankee Stadium Had Far Better Atmosphere Than New One Does,” CBS News, May 7, 2014, https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/mo-rivera-old-yankee-stadium-had-far-better-atmosphere-than-new-one-does.