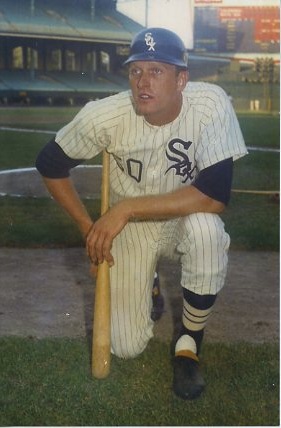

Cotton Nash

A superb college basketball player, Charles Nash became the University of Kentucky’s career scoring leader in the early ’60s. Yet baseball was his first love. “Cotton” — as he was known for his bright blond hair — was also a slugging first baseman/outfielder. He juggled the two sports as a pro, and though his time at the top levels was limited, he was still one of the rare men to play in both the NBA and the major leagues.1

A superb college basketball player, Charles Nash became the University of Kentucky’s career scoring leader in the early ’60s. Yet baseball was his first love. “Cotton” — as he was known for his bright blond hair — was also a slugging first baseman/outfielder. He juggled the two sports as a pro, and though his time at the top levels was limited, he was still one of the rare men to play in both the NBA and the major leagues.1

That pursuit proved detrimental. In 2000, Nash said, “It just got to be a grind because I didn’t have an off-season to recuperate. The mental and physical exhaustion from having to be at my very best every day hurt me in both sports.”2 In addition, a lingering ankle injury from his college days plagued him throughout his baseball career.3 While helping with this biography in 2010, Nash said that if he had to do it all over again, “I would probably have stuck with baseball. Hindsight, of course, is very clear.”

Charles Francis Nash was born on July 24, 1942 in Jersey City, New Jersey. His father, Frank Nash, was a safety engineer with Du Pont. Frank and his wife, Nell, also had a daughter named Francene. When Charlie was about 9 or 10 years old, an uncle started calling the towheaded youngster “Cotton-top.” The nickname stuck — even his wife calls him Cotton.

In 2008, Nash was interviewed by Ken Howlett for the Kentucky basketball website aseaofblue.com. He said, “The only sport we played in New Jersey was baseball. We had the Giants, Yankees, and Dodgers, and everyone dreamed of playing in the big leagues.”4 “My favorite was the Giants,” he said in 2010. “We all collected the baseball cards, and I just liked their cards better. But my favorite player was Mickey Mantle.”

At the age of 11, Nash discovered basketball when his family moved to Indiana, which — along with neighboring Kentucky — has a passion for hoops. When he went to Jeffersonville High School, his coach during sophomore year was Cliff Barker, a member of the Kentucky teams that won back-to-back NCAA basketball tournaments in 1948 and 1949. Jeffersonville is right across the Ohio River from Louisville, about 80 miles west of Lexington, where UK is located.

Frank Nash was transferred to Orange, in east Texas. The family found out that the Lone Star State had eligibility rules for high-school athletes — there was a one-year residency requirement. Since Louisiana was not as stringent, Frank decided that the family would live just across the border in Lake Charles. He made the sacrifice of commuting 40 miles each way every day for his son’s sake.5

At Lake Charles High, Nash became known as “The Bayou Bomber” for his basketball output. He was a star tight end in football, and even though the school had no baseball team, he still attracted scouts’ attention playing American Legion ball in the summers. In addition, he motivated himself to learn how to throw the discus and set a state high-school record. He could also run the 100-yard dash in around ten seconds.6

A Parade All-American in basketball as a senior, Nash had offers from more than 50 colleges around the country.7 When Ken Howlett asked him which options he considered, he responded, “Several Big 10 schools, Indiana and Michigan State, ACC schools. UCLA probably recruited me the hardest and longest.” Indeed, UCLA sought to entice the handsome young blond by offering a date with Jane Fonda! “I kinda had a crush on her and I mentioned this on my visit.”8

When it came down to it, though, Nash told Howlett, “I wanted to stay in the same geographical area. And if you were going to play basketball in the SEC, you had to play at Kentucky.” The Wildcats were coached by a basketball legend, Adolph Rupp. When Nash left Indiana, Cliff Barker had told Rupp to keep an eye on him.

In those years, freshmen could not play on the varsity, but while he waited, Nash set seven UK frosh records. As a sophomore, he immediately became a star. For lack of a true big man, Nash often served as a center, even though he stood just 6’5”.9 Yet he could and did play all positions. The game was not as specialized then; in particular, Rupp’s teams (by design) featured a balanced array of good all-around players. He could score from anywhere on the floor, with range up to 30 feet, a skillful lefty hook shot in the lane, and quick moves to the hoop. Atlanta sportswriter Furman Bisher raved after Kentucky beat Georgia Tech in a January 1962 game.

“You will seldom, if ever, see a boy so big with so much grace, so much agility, so much maneuverability and with so soft and velvety touch as Nash. There were times when Rupp was using this versatile young man to bring the ball down court when Georgia Tech pressed its defense. With his size and his massive hands, Nash gave the impression of a circus giant dribbling an orange.” Nash’s hands were the attribute that Rupp chose when he put together his ideal composite UK basketball player.10

“You will seldom, if ever, see a boy so big with so much grace, so much agility, so much maneuverability and with so soft and velvety touch as Nash. There were times when Rupp was using this versatile young man to bring the ball down court when Georgia Tech pressed its defense. With his size and his massive hands, Nash gave the impression of a circus giant dribbling an orange.” Nash’s hands were the attribute that Rupp chose when he put together his ideal composite UK basketball player.10

Since Nash was such a seemingly effortless player, inevitably some hypercritical fans thought that he wasn’t working hard. On the contrary, he said, “I just played as hard as I could for as long as I could.”11 Unfortunately, the Wildcats did not come close to winning an NCAA tournament in his time there. The field was much smaller back then, as only conference champions were invited. In 1962, Kentucky accepted the SEC bid because of Mississippi State’s “unwritten law” against playing integrated teams.12 They won one game and then lost to Ohio State as the great John Havlicek put his defensive clamps on Nash.

Hopes were high for the 1962-63 Wildcats — Nash made the cover of Sports Illustrated on December 10, 1962. In the accompanying article, Adolph Rupp said, “If I had my choice of one man in the country to build my team around, it would be Cotton Nash.”13 Mississippi State won the SEC title again in 1963, though, and this time the Bulldogs went to the NCAA tournament — despite efforts by segregationist forces to stop them.

By some accounts, Nash and Rupp clashed; by others, it was “an uneasy alliance.”14 When “The Baron of the Bluegrass” passed away in December 1977, though, Nash stated, “I just enjoyed playing for the man. I thought he was a very serious and upright coach. There were some players who quit and did not finish their four years. I was one that liked and took to his style of coaching and appreciated it. . .I, for one, wouldn’t have played for anyone else.”15 Over the years, Nash has often commented on how efficient and economical Rupp’s practice sessions were.

Nash hadn’t forgotten about baseball. “The fact that they let me play both sports” also led him to choose Kentucky.16 Rupp’s assistant, Harry Lancaster, was the head baseball coach. However, the NCAA basketball tourneys in 1962 and ’64 cut into his baseball time. “By the time I reported, there were only 15 or 16 games left.”17 Nash was called “a prospect in the $60,000 bonus class” in 1962.18 He pitched at UK and played the outfield, as well as a little shortstop.19 In 1963, he was the first baseman on the All-SEC team.

One amusing moment came against the University of Tennessee, as Vols coach Bill Wright remembered. “We had the winning run on second base when someone hit a fly toward Nash in left. Nash didn’t catch it, but he ran it down and made a strong throw in the general direction of home plate. At the end of the Kentucky bench was a water cooler and a big garbage can used for paper cups. Cotton Nash managed to throw that baseball into that can on the fly. I never saw anything like it, before or since.”20

In February 1963, there was rumbling that Nash might forego his senior year to play pro baseball. He said, “If something presented itself this summer, I’d have to think about it.”21 His family had moved yet again, to Leominster, Massachusetts — which meant that Nash played in the Cape Cod League in the summer of ’63. He helped Cotuit win the league championship.22 “It was just getting started then,” said Nash in 2010 (1963 was the first year of the league’s modern era). “Now it’s the premier summer league. It was a wonderful summer to spend, in that atmosphere. Scouts were talking to me, I could have gotten signed — but I did want to finish school.”

In Nash’s final year at Kentucky, he was SEC scoring champion again; the runner-up was future Cubs shortstop Don Kessinger of Mississippi (who stuck to baseball).23 For the third straight year, Nash was named an All-American. He was a consensus second-team pick as a sophomore and junior, but made the first team as a senior, also finishing a very close second in the voting for college basketball’s Player of the Year. In the NCAA tournament, though, after a bye it was “one and done” for the Wildcats. Nash had an off night in “the most astounding upset of the season.”24

Looking back on Nash’s college career, Cawood Ledford, the radio announcer who was “The Voice of the Wildcats” from 1953 to 1992, wrote, “I’ve never understood why Cotton Nash took so many knocks from the fans. Even though he was a three-time All-American, he was never able to satisfy everyone. As far as I’m concerned, they ought to build a monument to the guy. . .He absolutely carried the program on his back.”25 Nash averaged 22.7 points and 12.7 rebounds in 78 games on the varsity. As of 2018, he was still in the Top Ten in career scoring and rebounding for Kentucky.

Nash took part in trials for the U.S. Olympic basketball team in April 1964. Although he remembers being sick at that time, he was named one of seven alternates, ahead of stars like Billy Cunningham and Rick Barry. Making the 12-man squad at his position were other strong future NBA players: Bill Bradley, “Jumping Joe” Caldwell, and Jeff Mullins. The captain, Jerry Shipp from the Phillips 66ers, was yet another sharpshooting small forward. The international veteran was Team USA’s top scorer in Tokyo that October.

When asked if he would he have waited to turn pro if he’d made the first team, Nash responded, “Probably. I would love to have gone. I was very disappointed.”

On May 4, the Los Angeles Lakers selected Nash in the second round of the 1964 NBA draft. Twelve days later, he signed to play baseball with the Los Angeles Angels organization, which he chose over the Mets, Yankees, Reds, and Senators. The bonus was later disclosed to be $17,000.26 Money was not the central issue, however — Nash said, “I finally picked the Angels because I liked their representative (scout Carl Ackerman) and. . .[being] in the same city, I thought that way it might be easier to work something out to play two sports.” The Angels struck the normal contract clause about competing in another sport, and the Lakers did not object either.27

Nash first reported to Hawaii in the Pacific Coast League. He appeared in only two games, however, before the Angels moved him from Triple A to Single A. With the San José Bees, the new pro hit 11 homers in 86 games. Bees manager Rocky Bridges said, “Nash definitely has big-league potential. He stands deep in the box and swings with a wide arc. He just needs to make more contact. Around first base, it is mainly a matter of experience.”28

Nash reported to the Lakers that September, “barely taking time to change uniforms.”29 L.A. coach Fred Schaus, echoing his comments after the draft, said, “I like his [Nash’s] quickness. He looks like he might be a swing man between forward and guard.”30 The rookie made the team, but playing time was scanty. Nash was buried behind two of the greatest scorers in NBA history: small forward Elgin Baylor and guard Jerry West. The team also had another very capable veteran, Dick Barnett, and Don Nelson, who would later be an important part of champion teams with the Boston Celtics.

“I did play a lot in the exhibition season,” said Nash in 2010. “Elgin Baylor’s knees were bothering him. I carried around this thing called a hydroculator [a physical-therapy heating pad] for him. Then when the season started, all of a sudden his knees got better!” That November, the Los Angeles Times reported, “Close friends say Cotton Nash, the Laker-Angel rookie, is distressed over his lack of attention so far from Fred Schaus, and will soon quit the Lakers.31

A few days later, though, on November 18, Nash enjoyed his wedding to UK sweetheart Julie Richey. It took place in St. Patrick’s Catholic Church in her hometown, Mount Sterling, Kentucky.32 Cotton and Julie remained happily married as of 2018. Their three children — Patrick, John Richey, and Audrey — have given them eight grandchildren, including a set of triplets.

There were rumors that Nash would go to the San Francisco Warriors as part of a trade for Wilt Chamberlain, but Wilt went to Philadelphia instead. Nash wound up with the Warriors anyway, signing with them as a free agent a few days after the Lakers waived him in February 1965. He still didn’t get to play much — “it wasn’t a good situation for me. Their lineups were pretty much set. And I was really starting to feel it from playing all that baseball in the summer.” Nash’s only NBA season ended with an average of 3.0 points in 45 games played.

Nash spent the 1965 baseball season with El Paso in the Texas League (Double A). He hit well, with 22 homers, 77 RBIs, and a .294 average. The Warriors released him in early October that year, which put basketball on hiatus. “I decided to stay with my first love,” he said.

Moving up to Triple-A ball for 1966, although he hit some long homers, Nash endured a difficult year (.209-15-53). He split the season between Seattle, the Angels’ top farm team, and San Diego, which was in the Philadelphia chain. The Padres obtained him on loan in May but shipped him back in August after his ankle injury flared up.

Nash started the 1967 season back in El Paso. On May 6, the Chicago White Sox traded the veteran Moose Skowron to California, getting cash and Nash in the deal. Nash went to Evansville, also a Double-A team, and hit very well. The White Sox promoted him to Triple-A Indianapolis a little less than a month later upon recalling Ed “The Creeper” Stroud. He showed a lot of power, with 28 homers and 79 RBIs in just 100 games, while batting .274.

As early as June, though, Nash had one eye on basketball again. A new pro league, the American Basketball Association, had formed. One of the ABA’s tentpole franchises was the Indiana Pacers, and since he was in Indianapolis, Nash hoped to meet with them.33 Instead, he wound up with another ABA mainstay, the Kentucky Colonels. That August, Nash — “anxious to try out the new league” — signed with the Colonels.34 “They kept calling me and calling me,” he said in 2010. “They offered terms I couldn’t turn down.”

Chicago called Nash up when rosters expanded, and he got into three games during the pennant race. His debut came on September 1 at Fenway Park. With the Red Sox up 8-0, manager Eddie Stanky shuffled his lineup, and Nash entered the game at first base. He went 0 for 2 against José Santiago.

Nash’s greatest thrill in the game came just three days later. “We were at Yankee Stadium, out on the field for warm-ups. I looked over — and there he was, my childhood hero, Mickey Mantle.”

Nash’s next playing appearance, on September 10 in the first game of a doubleheader at old Comiskey Park, was his most notable in the majors: he helped save Joe Horlen’s no-hitter. In the ninth inning, Nash again replaced Ken Boyer at first. The first batter, Jerry Lumpe, hit a smash to second base. Wayne Causey made a diving stop and threw. In 1994, Causey said, “A faster runner might have beaten it out. I saw Lumpe’s foot coming down on the bag just as Cotton Nash took the throw.”35 Nash’s much longer stretch made the difference.

The ABA’s inaugural season started that October. Nash got more action than he did in the NBA, averaging 20 minutes and 8.5 points per game. He played forward, since the Colonels had a fine homegrown guard tandem in Louie Dampier and Darel Carrier. “I was in the starting lineup early in the season,” he said, “but then our coach [John Givens] was fired and the new one [Gene Rhodes] benched me the rest of the time.”36

After appearing in 39 games, Nash quit in January 1968. He told the Atlanta Constitution, “I didn’t feel I was helping the team very much, and I wasn’t playing too much either. Training camp begins soon, and I want to be in shape for the baseball season.”37 In 2010, he said, “I was thinking about halfway through that season, what have I done?”

Nash had a good camp with the White Sox — the Chicago Tribune wrote that “[his] fielding at first base improved greatly this spring and [he] was the only Sox player to hit two home runs in exhibition and inter squad play.”38 Incumbent Tom McCraw held the first base job, though, and after Nash went to the minors, the regular season was a washout. He hit just .179 in 42 games at Hawaii to start the year, and was sent down to Double-A Evansville, where things weren’t much better. “I’m still not sure why,” he said in 1970, but at some level he knew. “I decided that two sports was too much, that my baseball chances would be better if I gave up basketball.”39

In April 1969, the White Sox traded Nash to the Pittsburgh Pirates for pitcher Ed Hobaugh. He played 69 games for Columbus in Triple-A, but then the trade was voided as Hobaugh quit the Tucson Toros, Chicago’s new Triple-A team that year.40 Nash went to the Toros, but a week later, on July 15, he was dealt to the Minnesota Twins for a player to be named later (who turned out the following May to be Jerry Crider).

In 53 games with the Denver Bears, Nash was very productive in a new experimental role, designated hitter.41 Minnesota summoned him in September. He appeared in six games, notching his first big-league hit off Steve Barber of the Seattle Pilots at Sicks Stadium on September 25. The most intriguing note of that callup, however, was another experiment: manager Billy Martin tried Nash as a pitcher. “He had me throwing in batting practice almost every day for two or three weeks. When I wasn’t throwing, Early Wynn worked with me on the sidelines. I didn’t know whether to feel flattered or insulted. But I was in the big leagues then and I’d give anything to stay there.”42

Although the Twins fired Billy, putting an end to thoughts of Nash on the mound, they gave him a long look in spring 1970. However, he did not unseat Rich Reese at first base. At Triple-A Evansville, he hit 33 homers, leading the American Association. He earned his third and final cup of coffee that September, going 1 for 4 in four games. That brought his big-league totals to 3 for 19 (.188).

In 1971, Nash had his best year as a pro with the Twins’ new top affiliate, Portland. He was on pace for 50 homers in the early season and finished with 37, while driving in 102 and hitting .290. Yet the big club did not call him up at any point that season. “[Twins manager Bill] Rigney said in so many words he couldn’t use me this year, next year or ever. He said he’s got other guys who can play first base.”43 When Rich Reese hit poorly, Minnesota’s response was to shift Harmon Killebrew back to first for much of the year.

“Billy was fun to play for. He was a player’s manager,” Nash recalled with a chuckle in 2010. “After that, there was a lot of politics. There was the reserve clause then, you couldn’t play out your contract and leave. You were stuck. I don’t think they were real honest with me. I was just an insurance policy for Killebrew, [Tony] Oliva, and [Bob] Allison.”

Nash had asked to be traded, and the Twins obliged, sending him to the Boston organization in January 1972. It was a chance for him to perform for Kentucky fans once again, since the Red Sox had their top farm club in Louisville. But Nash was released (Cecil Cooper played first for the Colonels that year) and signed with the Texas Rangers chain in May. He played 64 games for Denver in the outfield and at first. He pitched once too, as he had done a couple of times in Portland.

After the ’72 season, Nash returned to his home and family in Lexington, where he was a real estate salesman. Early in his pro career, he had planned to become a dentist.44 “I was accepted to dental school, and I thought I’d try to do that along with baseball and basketball too, but there just wasn’t enough time to do three things.”

In February 1977, Nash returned to the diamond. His first organization, the Angels, hired him as a roving minor-league batting instructor. He told how it came about in 2010. “Back then the Cincinnati Reds, just up the road, were in all those World Series. I wanted to go, and I called the Reds about tickets. I was able to get them through the Angels office, and I wound up sitting with my old minor-league teammate, Tom Sommers. He had become the farm director.”

In 1978 Nash managed Quad Cities, California’s farm club in the Midwest League. He spent just one season as skipper, though — over 30 years later, he still sounded a little rueful about the experience.

“Let me tell you about managing. I had this Class A bunch, the youngest about 17, the oldest maybe 22. When we broke camp, I had 25 on the roster.45 I had one 21-year-old trainer, and that was the extent of my assistance. No pitching coach, nothing. Then they wanted to give me these five Dominicans they had signed, who didn’t speak a word of English. I just looked at them. The Dominicans went somewhere else.”

Nash owned his own real estate and investment company in Lexington, plus “a couple of other business ventures.” Lexington is “The Horse Capital of the World,” though, and Cotton and Julie have been breeding and owning standardbreds for around 30 years. Their horse Magic Shopper won the 1995 running of the Jugette, harness racing’s premier event for fillies. In the first decade of the 21st century, Miss Scarlett was their big winner. They later bred Rock N Roll Heaven, the horse that won the Little Brown Jug in 2010 and was named to the Harness Racing Hall of Fame in 2017.

In February 1991, an overdue honor arrived. The Lexington Herald Leader wrote, “Charles ‘Cotton’ Nash is still glowing about what happened to him last Sunday, when a University of Kentucky jersey bearing No. 44 was retired in his honor before the Georgia game. ‘For years I was basically ignored,’ Nash said. ‘It was really quite a shock, after all these years, to get some attention again.’ The credit goes to Athletics Director C.M. Newton, who has been working quietly to make things right.”46

That summer, Nash’s son Rich — who had played both basketball and baseball at Princeton — began a three-year minor-league career. Rich also spent a summer playing in Italy before establishing a career as an actor and writer under his full name, J. Richey Nash.

The Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame inducted Nash in 1993, even though his two years in Lake Charles were his only association with the state at all. Shortly after that honor, he also entered the Kentucky Athletic Hall of Fame. “I was surprised when I was informed,” he said.47 Yet he was too modest — over five decades after he graduated, people in the Bluegrass State still talk about Cotton Nash.

Last revised: March 27, 2018

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Cotton Nash for his memories (telephone interview, April 24, 2010). Thanks also to Ken Howlett for the introduction and to Richey Nash for the update (e-mail, March 27, 2018).

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett.

Sources

Online

www.baseball-reference.com

www.basketball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.bigbluehistory.net

www.capecodbaseball.org

Photo Credit

Courtesy of Cotton Nash collection

Notes

1 For discussion of who is on this list, see the biography of Chuck Connors by Charlie Bevis on the SABR BioProject.

2 Connie Aitcheson, “Cotton Nash, Kentucky All-America,” Sports Illustrated, February 21, 2000.

3 Mike Clark, “Nash To Return To Hardwood.” Kentucky New Era, February 24, 1977.

4 Ken Howlett, “Q&A with UK legend Cotton Nash.” Aseaofblue.net, July 2, 2008. (http://www.aseaofblue.com/2008/7/2/563388/q-a-with-uk-legend-cotton)

5 Dan Hruby, “Nash Keeps Two Irons in Fire; Baseball Rookie, Cage Prospect.” The Sporting News, August 22, 1964: 41.

6 Tev Laudeman, “Kentucky Makes Cage Hay as Cotton Shines,” The Sporting News, January 31, 1962: Section 2, 2.

7 “Kentucky Lands Star Netter Charles Nash,” Associated Press, August 16, 1960.

8 Cawood Ledford, Heart of Blue, Lexington, Kentucky: Host Communications, 1995: 58.

9 According to basketball references; baseball references show him at 6’6”. In Nash’s own words, “6’5” is a pretty good average.”

10 Russell Rice, Adolph Rupp: Kentucky’s Basketball Baron, Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 1994: 166, 207.

11 Howlett, op. cit.

12 SEC basketball did not become integrated until Perry Wallace of Vanderbilt won a scholarship in 1966 and joined the varsity in 1967.

13 “3 Kentucky,” Sports Illustrated, December 10, 1962.

14 Rice, Adolph Rupp: Kentucky’s Basketball Baron, 168. Tev Laudeman, “Kentucky’s ‘Little Guys’ Burn Up Court,” The Sporting News, February 1, 1964: 29. Tom Wallace, Kentucky Basketball Encyclopedia. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 1994: 152.

15 “Ex-Player Kron: There’ll Never Be Another Rupp,” Associated Press, December 11, 1977.

16 Howlett, op. cit.

17 Hruby, op. cit.

18 Hap Holbrooks, “What Next After Snow In Southern California?” Florence (Alabama) Times, January 23, 1962: 10.

19 Pete Swanson, “Nash, Triplet Homer King, Narrowly Escaped Hill Job,” The Sporting News, August 22, 1970: 35.

20 Marvin West, Tales of the Tennessee Vols, Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2002: 162.

21 “Will Nash Turn Pro? Kentucky Cager Hedges On Rumors,” Associated Press, February 20, 1963.

22 “Nash Two-Sport Pro,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1965:2.

23 “Several [NBA] clubs asked me, if they drafted me would I play basketball,” Kessinger said, “but I answered them honestly and said, ‘No, I want to play baseball.’” Lew Freedman, Chicago Cubs: Memorable Stories of Cubs Baseball, Champaign, Illinois, Sports Publishing LLC, 2007: 65.

24 Joe Gergen, “Ohio Oniversity stuns Kentucky in 85-69 upset.” Associated Press, March 14, 1964.

25 Cawood Ledford with Billy Reed. Hello Everybody, This Is Cawood Ledford, Lexington, Kentucky: Host Communications, 1992: 99.

26 Ross Newhan, “Angels Protect Cherub Talent, Vets Cut Loose,” The Sporting News, November 6, 1965: 21.

27 Hruby, op. cit.

28 Ibid.

29 “Cotton Nash Joins Lakers,” Los Angeles Times, September 9, 1964: E3.

30 “Nash Sparkles in Laker Drill,” United Press International, September 4, 1964.

31 Los Angeles Times, November 14, 1964: A3.

32 “Cotton Nash Is Wed to Excoed,” Associated Press, November 19, 1964.

33 “Nash Eyes Basketball,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1967: 31.

34 “Colonel Five Signs Nash,” New York Times, August 9, 1967: 35; “Cotton Busy on Day Off; Inks Pro Cage Contract,” The Sporting News, August 26, 1967: 33.

35 Jerome Holtzman, “Bob Locker Still in There Pitching for Old-Timers’ Relief.” Chicago Tribune, October 2, 1994: 11.

36 Dale McKean, “50-Homer Season for Nash No Longer ‘Ridiculous’ Goal.” The Sporting News, May 22, 1971: 39.

37 “Cotton Nash Quits Pro Basketball,” Associated Press, January 23, 1968.

38 “Sox Trim Six More Off Roster,” Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1968: B2.

39 Swanson, op. cit.

40 The Sporting News, July 19, 1969: 38.

41 “Nash Top DPH,” The Sporting News, September 6, 1969: 34.

42 Swanson, op. cit.

43 McKean, op. cit.

44 Hruby, op. cit.

45 His squad included five future big-leaguers: Brian Harper, Brad Havens, Daryl Sconiers, Alan Wiggins, and Mike Bishop. Bert Blyleven’s little brother Joe, also a pitcher, was there too.

46 “UK Honoring Nash Was Long Overdue,” Lexington Herald Leader, February 8, 1991: B1.

47 “Oh, What a Feeling: Nash Heads List of Athletes Tapped for Kentucky Hall of Fame,” Lexington Herald Leader, July 4, 1993; C12; “Nash helped put Wildcats on the basketball map,” The Advocate (Baton Rouge, Louisiana), June 23, 1993.

Full Name

Charles Francis Nash

Born

July 24, 1942 at Jersey City, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.