Rocky Bridges

Rocky Bridges an All-Star? “They were close to launching an investigation,” he said after being named to the 1958 American League All-Star team.1 Bridges made the squad as the token representative of the last-place Washington Senators, but for most of his 11-year big-league career he was the designated comedian for seven teams, a utility infielder who delivered more one-liners than line drives to the amusement of teammates and sportswriters who could always count on him for a quip and a quote.

Rocky Bridges an All-Star? “They were close to launching an investigation,” he said after being named to the 1958 American League All-Star team.1 Bridges made the squad as the token representative of the last-place Washington Senators, but for most of his 11-year big-league career he was the designated comedian for seven teams, a utility infielder who delivered more one-liners than line drives to the amusement of teammates and sportswriters who could always count on him for a quip and a quote.

He was instantly recognizable by the mammoth chew of tobacco swelling his cheek and a clownish face that “looks like a blocked punt,” as writer Dick Miller described it.2A baseball lifer, Bridges managed in the minors for 20 seasons from rookie league to Triple A. At one of his stops, he said, “I managed good, but boy did they play bad.”3

Everett Lamar Bridges Jr. was born in Refugio, Texas, on August 7, 1927, nearly 20 years before the town’s most famous son, Nolan Ryan. His parents were Annette Edith (Franz) and Everett L. Bridges, an oilfield worker, but the boy was raised by his paternal grandmother Adelia Bridges, in Long Beach, California. The available record reveals nothing else of his Depression-era upbringing.

He attended a Brooklyn Dodgers tryout camp in 1946 but heard nothing from the team afterward. He spent his last nickel on a streetcar ride to see scout Tom Downey and beg for a job. Downey signed him, but didn’t offer even a five-cent bonus, so young Bridges had to walk home.

Before he could begin his baseball career, he was drafted into the army. That lasted only a few months, until he contracted rheumatic fever and was granted a medical discharge. Joining the Dodgers’ Class-C farm club in Santa Barbara, California, in 1947, he played in only 39 games before a broken leg ended his season. The next year, at Class-A Greenville, South Carolina, he picked up his enduring nickname. Either a teammate or a broadcaster or a public address announcer (he told it all three ways at different times) explained that he looked like he should be called “Rocky.”

By any name, he looked like a prospect. Bridges was the Sally League’s all-star shortstop at Greenville in 1948 and two years later finished second in the Triple-A International League MVP vote at Montreal. The honors mostly paid tribute to his glove work; at 5-feet-8 and around 170 pounds, he was only a fair hitter with little power, but could steal bases and draw walks. Montreal Gazette writer Lloyd McGowan described him as “no beauty, just all ballplayer.”4

After just three full seasons in the minors, Bridges won an invitation to major-league spring training in 1951. He was given little chance of making the team, because the Dodgers had Pee Wee Reese entrenched at shortstop and his heir apparent, Bobby Morgan, in a utility role. Bridges stood out for his hustle and his stream of tobacco juice and wisecracks, “a tobacco-chewing, cigar-smoking hunk of muscle,” veteran writer Tommy Holmes called him. “He’s just a spare infielder, technically a shortstop,” Holmes wrote, “but he’s got more fire, more spirit, more get up and go on the field and more balance both on and off the diamond than most fellows ever thought of having.”5

Manager Charlie Dressen agreed: “He’s the one who showed the most life out there. He loves to play ball and I’m going to give him a chance.”6 Bridges was the Opening Day starter at third base, but after six games he had amassed just two hits and went to the bench. For the rest of the season, he served as a utility infielder, filling in at second, third, and short while compiling a .634 OPS in 63 games. The next year he played even less often, mostly as a defensive sub, with only 66 plate appearances in 51 games. His OPS fell to .536.

Midway through the 1952 season, Bridges was sent down temporarily when three of Montreal’s infielders got hurt. Just one hitch: he was scheduled to get married eight days later. “If any of you guys get to my wedding,” he told teammates, “let me know what happened.”7 Fortunately, his emergency assignment in Montreal lasted only five days, and he returned to Brooklyn to marry Mary Alway with Reese as his best man.

During the winter, the Dodgers let Bridges go in a trade involving five players and half the teams in the National League. Bridges went to the Boston Braves as part of a package for pitcher Russ Meyer. Boston then flipped him to Cincinnati for a powerful young first baseman, Joe Adcock, who was blocked behind Ted Kluszewski in the Reds’ lineup.

It looked like a lopsided deal: a backup infielder batting .196 for a slugger who had hit 13 home runs as a part-timer and would go on to hit 336 homers in his career. But Cincinnati manager Rogers Hornsby wanted Bridges. “That Bridges is my kind of player,” he told sportswriters. “He fights. He likes to win. He never gives up. Six guys like him can win you a pennant over a bunch of prima donnas with talent to spare and nothing up here”—he pointed to his heart. The sour-tempered Hornsby seldom showed such enthusiasm for any player. “One thing I know,” he added, “(Grady) Hatton or (Johnny) Temple will never chase Bridges off second unless they go all-out. For that’s the way he plays—all out.”8

Hornsby staged a springtime competition for the second base job pitting Bridges against Hatton, the incumbent, and the rookie Temple, but he sounded like he had already made up his mind. He awarded the position to Bridges alongside the smooth shortstop, Roy McMillan. “Those two kids will give us the best double-play combination in the majors this season,” the manager declared.9

While their gloves sparkled, their bats sputtered. Bridges hit .227, McMillan .233. Cincinnati sank to sixth place for the fourth straight year, and manager Hornsby didn’t last the season. In 1954 new manager Birdie Tebbetts turned second base over to Temple. Bridges was again a utility man for the next three years.

He was approaching his 30th birthday early in the 1957 season when the Redlegs put him on waivers and sold him to the Washington Senators. Bridges said he was glad to spend four years in Cincinnati because “it took me that long to learn how to spell it.”10 The deal was arranged by his former Dodgers manager Dressen, who had just been relieved of his duties managing Washington and kicked upstairs to the front office.

The Senators installed Bridges as their regular shortstop, although he hit only .228 after the trade. The next year he got off to a hot start and was batting over .300 in June. The waiver pickup became an All-Star. He finished third at shortstop in the voting by players and coaches, behind Chicago’s Luis Aparicio and the Yankees’ Tony Kubek, and All-Star manager Casey Stengel chose him as Washington’s only representative on the team. “For me, it was as big a thrill as being in the World Series,” he gushed. He didn’t play in the game, but reveled in sitting alongside the other substitutes such as Ted Williams, Yogi Berra, and Al Kaline. 11

Bridges didn’t get much time to savor his brush with immortality. In his first plate appearance after the All-Star break, a pitch from Detroit’s Frank Lary broke his jaw. He missed more than a month while suffering the tortures of damnation. With his jaws wired shut, he couldn’t chew tobacco or smoke a cigar. Nor eat solid food; when he returned to action, he was weak, and his final batting average fell to .263.

The Senators, evidently following advice to “buy low, sell high,” traded their All-Star shortstop to Detroit at the winter meeting, but failed to acquire an adequate replacement. Bridges got off to another strong start with the Tigers in 1959, hitting close to .300 at the All-Star break, before another injury ruined his season. Torn tendons in his left ankle cost him most of the second half and pulled his average down to .268.

That ended his days as a regular player. Detroit acquired Chico Fernandez to play short in 1960 and swapped Bridges to Cleveland in July. The Indians passed him on to St. Louis in September, and the Cardinals released him after the season.

Major league expansion extended his career. The new Los Angeles Angels signed him as a free agent, adding him to their collection of castoffs found wanting by other teams. Bridges signed for $12,500, his biggest salary. Los Angeles sportswriters welcomed the arrival of a man who always made good copy; one writer called him “the baggy-pants comedian of the baseball diamond.”12 He opened the season on the bench, but soon got regular playing time at short and second as manager Bill Rigney shuffled players in search of a winning combination. The Angels won 70 games, the most ever by a first-year expansion club, with Bridges contributing a .240 batting average in 84 games.

His highlight was Fourth of July fireworks. He hit his first home run in more than two years, a three-run shot off Kansas City’s Bill Kunkel that gave the Angels the lead in the second game of the holiday doubleheader. The home crowd rewarded him with a standing ovation, and he flexed his muscles as he crossed the plate. “It wasn’t very dramatic,” he said. “No little boy in the hospital asked me to hit one. … I hit it for me.”13

At the end of the season, the team released the 34-year-old, and then signed him as a coach. His big-league playing career spanned 447 games at shortstop, 270 and second, 191 at third, and 1 1/3 innings in left field during 11 seasons with seven teams. “I’ve had more numbers on my back than a bingo board,” he quipped.14

When the Angels soared to a third-place finish the following year, Bridges remarked, “The ’62 club got a big break. I retired and became a coach.”15 He coached first base and third in 1962 and 1963, then the Angels sent him off on his second career as a minor-league manager. Over the next 25 years, that career wound through nine stops from Buffalo to Honolulu. His teams won 1,301 games and lost 1,358.

He managed in four organizations — the Angels, Padres, Giants, and Pirates — littering the landscape with one-liners along the way. His favorite drink was two jiggers of Scotch and one of Metrecal: “So far I’ve lost five pounds and my driver’s license.”16 Making fun of his appearance, he said, “It’s an upset when I don’t make the all-ugly team.”17

He rejoined the Angels as a coach from 1968 through 1971. During that period, he moved his wife and four children to a farm outside Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, because “Up here they don’t know a damn thing about me, so I can tell them how great I was.”18

Bridges’ longest stint was nine seasons managing the Giants’ Triple-A club in Phoenix. For the first eight of those years, he walked three miles from his hotel to the ballpark every day. In his ninth season, he lived in the clubhouse. The Phoenix Giants won one pennant, and Bridges was twice named Pacific Coast League manager of the year. Finally, the Giants brought him up as a major-league coach in 1985. The team’s young shortstop, José Gonzalez, decided his name was too common for him to stand out, so he began using his mother’s surname, Uribe. “He’s literally the player to be named later,” Bridges observed.19

Bridges’ return to the majors lasted only a year before he was fired in a change of managers. The Giants hired five managers during his time in the organization, but he apparently never received serious consideration. In the competition for those jobs, Bridges’ personality was a handicap. “He’s one of those people who has a reputation more for being a character than his baseball knowledge,” said his friend and Pirates manager Jim Leyland. “But he knew the game…. If he said a guy couldn’t play, he couldn’t.”20

Bridges also had a reputation as a player’s manager because he never rode his charges too hard. He believed too many teams were guilty of “overcoaching,” even at the big-league level. “I think sometimes we fill them up with too much stuff instead of just letting them play,” Bridges said. “I think everybody is a hitting coach now and I haven’t seen a hitter made yet.”21

He finished his managing career with four years in the Pittsburgh farm system, then stayed with the Pirates as a roving minor-league instructor until he retired at 68 in 1995. He admitted that in the final years he struggled to connect with young men who chewed sunflower seeds instead of tobacco. “I’m afraid my players will start molting,” he said, “or going to the bathroom on newspapers.”22

Bridges was 87 when he died on January 28, 2015. He had no trouble naming the highlight of his long career. “Being there,” he said. “Being where a lot of people would have loved to have been.”23

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Photo credit

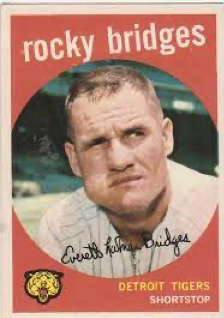

Courtesy of The Topps Company.

Notes

1 Jerry Crowe, “For Bridges, baseball really was fun and games,” Los Angeles Times, July 25, 2011: C2.

2 Dick Miller, “Rocky Recalls Angel Milestones,” The Sporting News (hereafter TSN), March 13, 1971: 49.

3 Crowe.

4 Lloyd MGowan, “Bridges Being Boomed as Next Royals Shortstop,” Montreal Gazette, March 18, 1949: 32.

5 Tommy Holmes, “About a Couple of Real Dodgers,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 27, 1951: 14.

6 Joe King, “Scrappy Spirit Speeds Up Rocky’s Road,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1951: 5.

7 “Loan Bridges to Montreal in Emergency,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 18, 1952: 12.

8 United Press, “Bridges Battles Hatton, Temple for 2d Base Slot,” Brooklyn Eagle, March 2, 1953: 13.

9 Lou Smith, “Cards Will Be Better, Stanky Says,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 14, 1953: 30.

10 Ross Newhan, “Angels Holding Sides; Rocky’s Back in Town,” TSN, December 23, 1967: 30.

11 “Rocky Bridges Gets His ‘Greatest Thrill,’” Washington Post and Times Herald, July 9, 1958: A17.

12 “Angels Sign ‘Our Rocky,’” Long Beach (California) Press-Telegram, January 14, 1961: C-1.

13 Newhan, “Angels Holding Sides.”

14 Newhan, “Angels Holding Sides.”

15 Miller, “Rocky Recalls Angel Milestones.”

16 Crowe.

17 Bob Addie’s Column,” Washington Post and Times Herald, June 2, 1957: C2.

18 Crowe.

19 “Hammaker to Open, Giants Still Juggling,” San Francisco Examiner, March 30, 1985: C4.

20 Tracy Ringolsby, “From humor to knowledge, Bridges a vintage baseball guy,” mlb.com, January 30, 2015.

21 Dan Weaver, “Rocky Recalls ‘Beer-Crowd’ Boys,” Spokane Chronicle, November 10, 1982: D1.

22 “Names and Games,” Pittsburgh Press, June 5, 1989: D2.

23 Howie Stalwick, “Bridges Retires Still One of a Kind,” Baseball America, April 2, 1995, in Bridges’ file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

Everett Lamar Bridges

Born

August 7, 1927 at Refugio, TX (USA)

Died

January 28, 2015 at Coeur d'Alene, ID (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.