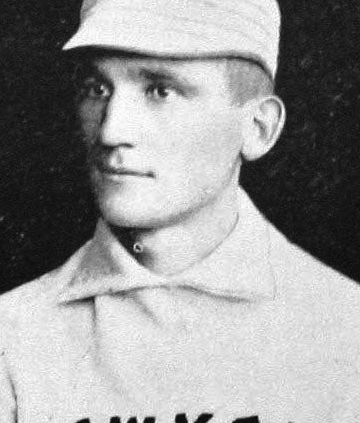

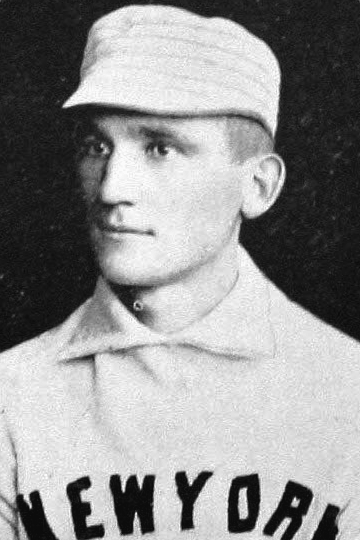

William Brown

The game of baseball attracts all types of personalities, from the angry to the stoic to the eccentric to the comedic and everything in between. William M. “Big Bill” Brown, who played in the majors from 1887 through 1894, definitely falls into the comedic category, though he was also quite serious about the game. Though he played more at first base in the majors, Brown may be best remembered as a catcher. In the latter role, he had a penchant for talking to batters, giving them bad advice. As historian David Nemec wrote, “the big redheaded backstop would also play on a batter’s nerves by pretending sotto voce to side with him in protesting an umpire’s questionable strike call.”1 Brown was doing what Yogi Berra made famous over a half a century later – though unlike his 20th century counterpart, Brown is all but forgotten.

The game of baseball attracts all types of personalities, from the angry to the stoic to the eccentric to the comedic and everything in between. William M. “Big Bill” Brown, who played in the majors from 1887 through 1894, definitely falls into the comedic category, though he was also quite serious about the game. Though he played more at first base in the majors, Brown may be best remembered as a catcher. In the latter role, he had a penchant for talking to batters, giving them bad advice. As historian David Nemec wrote, “the big redheaded backstop would also play on a batter’s nerves by pretending sotto voce to side with him in protesting an umpire’s questionable strike call.”1 Brown was doing what Yogi Berra made famous over a half a century later – though unlike his 20th century counterpart, Brown is all but forgotten.

Born to Irish immigrant parents in San Francisco, Brown’s exact month and date of birth are unknown. Those records may have been destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and the subsequent fire that destroyed 80% of the city. Brown was born around 1866, based on the 1870 US Census record. Both of his parents, Michael and Margaret Brown (née Besson) were born around 1835 (though the 1900 census states she was born in July 1830). It is unclear when they came to the United States. However, it had to be 1855 or before, because their eldest child, Andrew, was born in Pennsylvania that year.2 There is also a marriage certificate matching the couple’s names issued on January 30, 1856, in Chicopee, Massachusetts. However, it is impossible to determine if this is the same duo – both their given names and surname are very common. The large numbers of Irish immigrants coming to these shores during the early to middle part of the 19th century also support the possibility of a coincidence.3

Regardless, the Brown family can be found in the 1870 US Census living in San Francisco. Their second child, Mary, was born in California in 1857, putting their move to the state sometime between 1855 and 1857. Brown’s other siblings listed at this time were John, Annie, and Fanny. In the 1880 US Census, another brother, Tom, was added to the brood.4 In both census records, Michael’s occupation is listed as “Teamster”; the 1880 census lists Margaret’s occupation as “Keeping House.”5 This is the extent of information found on Brown’s pre-baseball years. In 1882 he entered baseball’s historical record.

On April 17, 1882, the San Francisco Daily Examiner published a box score of a game between the San Francisco Californians and the San Francisco Nationals of the California League. Catching for the Nationals is “B. Brown.” According to the writeup (though not documented in Baseball-Reference.com), he went 0-for–4 at bat, with one put out and one assist.6

From 1883-1885, Brown’s movements are a mystery as it stands. Based on currently available information, he didn’t surface again until the 1886 season, when he was playing for the Greenhood & Moran Nine (sometimes listed as just Greenhood & Moran), most likely sponsored by the store of the same name on Eleventh and Broad Way in Oakland, California.7 The team was also part of the California League.8 The earliest known box score containing his name that year can be found in the Oakland Daily Evening Tribune of July 12. Again, he went 0-for–4 at bat; in the field he had four putouts, five assists, and three errors. On this team was another future major-leaguer, George Van Haltren.9

It was during this time that Brown acquired one of his many nicknames, “Baby” or “Baby Brown.” Other nicknames were “California,” “Reddy,” “Will,” and “Sailor” – the most popular, “Big Bill” (or “Big Will”), because he was six-foot-two and 190 pounds, would soon follow.10 The clean-shaven redhead was a right-handed thrower and batter.

It was also at this time that his skills as a batter drew the attention of a team from the opposite coast, the New York Giants of the National League.11 Brown finished out the season in the California League but would soon head east on his way to the majors.

After playing with various California teams at the start of 1887, on March 23 Brown left San Francisco with a $300 advance to meet up with his new team, the Giants.12 He debuted as a right fielder on May 10, but soon moved behind the plate, his primary position during his first few years in the majors.13 He was the batterymate of future Hall of Famer Tim Keefe. Later, Keefe remembered how Brown would talk to batters, trying to psych them out. The pitcher stated that Brown would begin with something like, “Say, old sport, the people are beginning to think you can’t hit. I know you can. Keefe is pretty good today, but if you keep your eyes open, I’ll give you a tip what’s coming.” Then Brown would say, “Here comes a curve,” and the ball would come straight over the plate. The umpire would call a strike and Brown would say to the batter, “That was no strike. He’s roasting you. Now here’s a straight one coming.” Keefe would pitch a curve just outside, and as the batter missed it, Brown always said, “You just hit an inch over it. If you’d nailed it, you’d have made a homer.”14

Another example of his humor came from August 23 when a game at the Polo Grounds against Pittsburgh was rained out. The home team hung around the clubhouse and met their new third baseman, John Rainey. In typical fashion, Brown said, “Well, Mr. Rainy [sic], I am glad to see you, but I don’t like your weather.”15

Sparingly used that season, Brown wound up with a .218 batting average and a .914 fielding percentage over 46 games as catcher.

The 1888 season started out with a contract dispute between Brown and the Giants. Brown wanted $3,200 or he was staying in California.16 However, it didn’t take long to iron out a deal for $2,300.17 Over the next two seasons the Giants won back-to-back pennants. Brown was a useful reserve catcher behind the primary starter, Buck Ewing. In 1888, he was third-string behind Pat Murphy but became Ewing’s primary backup the next year. A writer from the Buffalo Sunday Morning News stated at the end of the 1888 season that “[Brown] can stand no end of punishment from wild pitchers without showing the slightest signs of pain. This season his work has surpassed that of 1887.”18

That same season, the Giants met the President of the United States, Grover Cleveland, in the East Room of the White House. When it came time to shake the President’s hand, Brown said to him, “No Chinese labor for me.”19 The exact meaning of this comment is unknown. It may have been a reference to the Chinese workforce found across the western half of the continent, particularly in California. However, we will never know for sure what he meant.

Brown was visible in postseason play in both 1888 and 1889. In the 1888 World’s Series against the St. Louis Browns, he got into eight of the 10 games as the Giants won, six games to four. New York defeated the Brooklyn Bridegrooms in the 1889 edition, six games to three. Brown took part in five of those games. Altogether, he went 6-for-13, including a double and homer in Game Five in 1889 off Bob Caruthers at Brooklyn’s Washington Park. Of that game, Sporting Life wrote, “Brown caught instead of Ewing. He made some excellent stops of wide-pitched balls and batted terrifically.”20

Though he loved to kid and play pranks, Brown could play some serious ball. Whether it was hustling to get King Kelly out, catching a foul pop from Doggie Miller, or putting on a battery exhibition with John Tener, Brown put his heart and soul into his work.21

The year 1890 was an odd one for baseball, with many players jumping to the Players League. Brown went with other Giants to the upstart association. He also owned a $1,000 “block of stock” in the new league from which he hoped to profit.22 However, while playing on a team in Los Angeles before the start of the season, Brown broke his nose. This would be the first of many injuries and absences to come.23

The Players League collapsed at the end of the 1890 season, Brown finished with a .278 batting average – including a career-high four homers in 60 games – and a .900 fielding percentage with the circuit’s New York franchise,

Brown re-signed with the NL Giants in 1891. It was reported in April that he was seriously ill and would be out for months; however, by the end of the month he was better. Also, he had signed with the Philadelphia Quakers after New York released him.24 In a 14-inning game on May 13, Brown had four hits and accepted 21 chances without an error. This game and the ability he displayed throughout that season led to the papers to observe that New York made a mistake letting him go.25

Brown got into 115 games in 1891, mainly at first base, and hit. 243 with no homers and 50 RBIs. However, that was the only season he spent with Philadelphia. In 1892, the Quakers released him. Brown was seriously ill in the early part of the season with an abscess on his leg, which caused him to lose 30 pounds in one month.26

Brown stuck to the West Coast and played for four teams that season. He started in the California League with the Oakland Colonels in May; in August he was in both the California League with the San Francisco Metropolitans and in the Central California League with the Oakland Morans and Vallejo.27

Illness again plagued Brown in the 1893 season, which started with him being signed and quickly released by the Baltimore Orioles. On April 9 it was announced that he was playing for Baltimore. However, by May 20 he was replaced by Jocko Milligan.28 The nature of his illness is unknown. Eight days later the papers announced that he had signed with the Louisville Colonels.29 Brown continued to occupy first base.30 While in Louisville he put up the best batting average of his major-league career: .304, bringing his mark for the season up to .292 in a career-high 118 games. His 90 RBIs were also by far the most he had in any season. He also gained a lot of weight, to the point that one paper called him “enormous.”31

More bad news and illness were to come for Brown in 1894. Though he started out well playing for Oakland in the California Players League, he came to Louisville and was released after only three games in May.32 The papers noted that manager Billy Barnie made an example out of Brown to show the team he was angry with their poor performance.33 Brown was picked up by St. Louis and released three days later, This was his final season in the majors. He finished with a .261 batting average and a .960 fielding percentage after seven seasons.

Brown stayed active in the minors with the Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Coal Barons of the Eastern League. Though it took him a while to warm up, he did well with a .288 batting average.34 Despite being popular with the fans, Brown also got into a bar fight and took a beer bottle to the eye.35 He also angered management when he refused to give back an extra $42 that he got in his paycheck. The Coal Barons had advanced Brown $42 when he came to Wilkes-Barre. When it came time to give him his salary, they forgot to deduct the advance. Refusing to refund the sum already paid, he was benched for what one paper called “ungentlemanly and indecent behavior.”36 He never played for Wilkes-Barre again. It is also unclear if he ever gave the money back.

The following year, 1895, Brown disappeared. The papers mentioned that he “dropped out of sight all together.”37 If or for whom he played baseball is unknown.

Brown’s final year in the game came in 1896, when he signed to play for the Seattle Rainmakers of the New Pacific League. One paper wrote that “he recovered and was now playing for Seattle.”38 This could be the reason for his absence in 1895, but it’s pure speculation. At this time, Brown was suffering from the early stages of tuberculosis and played only 15 games before having to quit.39

During the late 19th century there was no cure for TB. The usual treatments were going to a sanatorium, bleeding, or moving to a cooler mountainous climate with lots of exercise and fresh air. It should be noted that none of these cures really worked.40 Brown moved around. He went to Arizona, Mexico, Southern California, and the Hawaiian Islands, living in Honolulu for a time.41

Nothing helped. William Brown died on December 20, 1897, at his mother’s home in San Francisco.42 In the obituary published in the Wilkes-Barre Record, it was said that Brown had predicted that he would be a victim of lung trouble.43 His fear was commonplace – consumption (as the disease was then often known) was the scourge of late 19th century Irish-Americans, with many families being ravaged by it. Brown was first buried in Calvary Cemetery in San Francisco. However, the city council suspended any further burials in city limits; he and others were subsequently disinterred and reburied in Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery. He is in the family plot with his mother and father and marked only by a stone that reads “Brown.”44

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Tony Oliver.

Photo credit: Public domain.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and the following:

Ancestry.com

Findagrave.com

Newspapers.com

US Census Bureau, 1870, 1880, 1900 US Census

Notes

1 “Current Sporting Talk,” (New York) Sun, December 23, 1897: 4; David Nemec, Major League Player Profiles: The Ball Players Who Built the Game, Vol. 1, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press (2011): 295.

2 1870, 1880, and 1900 US Census.

3 Margaret Brown marriage certificate.

4 1870 and 1880 US Census.

5 1870 and 1880 US Census.

6 “Baseball,” Daily Examiner (San Francisco), April 17, 1882: 3.

7 “Home Hand Made,” Oakland Evening Tribune, July 3, 1886: 2.

8 “Diamond Dust,” Oakland Evening Tribune, November 6, 1886: 1.

9 “An Oakland Victory,” Oakland Evening Tribune, July 12, 1886: 2.

10 “Excelsior,” Oakland Evening Tribune, August 2, 1886: 2. “The Game,” Oakland Evening Tribune, October 11, 1886: 3.

11 Nemec, 295; “One of Bill Brown’s Jokes,” Boston Globe, August 24, 1887: 3.

12 “G. & M.’s Vs. Pioneers,” Oakland Evening Tribune, February 21, 1887: 2; “All Around Notes,” Oakland Tribune, February 28, 1887: 2, “Diamond Dust,” Oakland Evening Tribune, March 24, 1887: 2.

13 “The Score,” Sporting Life, May 18, 1887: 2.

14 “Brown as a ‘Jollier,’” Trenton Evening Times, December 23, 1887: 6.

15 “One of Bill Brown’s Jokes,” Boston Daily Globe, August 24, 1887: 3.

16 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, April 12, 1888: 4.

17 “The Ball-Players,” (Salisbury) Connecticut Western News, May 2, 1888: 4; “Bunched Hits,” Daily Examiner, October 15, 1888: 6.

18 “Top of the Heap,” Buffalo Sunday Morning News, October 14, 1888: 6.

19 “The Giants See the President,” San Francisco Daily Examiner, September 9, 1888: 16.

20 “The World’s Series,” Sporting Life, October 30, 1889: 3.

21 “A Bracer. The New Yorks Get It Somewhere and Do Up the Bostons,” (New York) World, May 9, 1889:1; “Short, But So Amusing,” The World, May 18, 1889: 1; “Extra, It’s Ours!” World, May 24, 1889: 1.

22 “The Colonel Take the Last Game of the Series from Los Angeles,” San Francisco Daily Examiner, March 17, 1890: 3.

23 “Baseball Gossip,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, April 20, 1890: 20.

24 “Base Ball Notes,” Boston Daily Globe, April 9, 1891: 9; “Sporting Gossip,” Burlington (Vermont) Free Press and Times, April 21, 1891: 2.

25 “Base Ball Notes,” Boston Globe, May 15, 1891: 9; “Is Buck Shirking,” Pittsburg Press, May 18, 1891: 5.

26 “Notes of the Game,” San Francisco Daily Examiner, April 23, 1892: 8; “Chat of the Diamond,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 2, 1892: 3.

27 “Baseball Notes,” Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1892: 6; “San Francisco’s Day,” San Francisco Daily Examiner, August 15, 1892: 4; “Lost by One Run,” San Francisco Daily Examiner, August 19, 1892: 8.

28 “Chat of the Diamond,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 9, 1893: 16; “World of Sports,” Waterbury (Connecticut) Evening Democrat, May 17, 1893: 4; “Notes and Comment,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 20, 1893: 5.

29 “Louisville Changes,” St. Paul Globe, May 28, 1893: 5.

30 “Baltimores, 5; Louisvilles, 3’” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 6, 1893: 5.

31 “World of Sports,” Waterbury Evening Democrat, September 9, 1893: 4; “Won Fifteen Games,” (Louisville) Courier-Journal, September 10, 1893: 10.

32 “Last of the Series,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 8, 1894: 5; “All Sorts from the World of Sports,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 1, 1894: 10; “Bill Brown Released,” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, May 9, 1894: 6.

33 “The Browns Were Not in It,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 10, 1894: 9.

34 “Ball Notes,” (Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania) Evening Leader, July 19, 1894: 2; “Ball Notes,” Wilkes-Barre Evening Leader, July 20, 1894: 2.

35 “Among the Base Ball Players,” Evening Leader, July 30, 1894: 6; “King Keenan Saved the Game,” (Wilkes-Barre) Sunday News, June 24, 1894: 4.

36 “Why Do We Lose,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Record, August 10, 1894: 7; “Ball Notes,” Evening Leader, August 11, 1894: 2.

37 “Base Ball Stars,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune, July 24, 1894: 7.

38 “On the Diamond,” Evening Leader, April 10, 1896: 7.

39 Nemec: 295.

40 “Early Research and Treatment of Tuberculosis in the 19th Century,” The American Lung Association Crusade, (http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/alav/tuberculosis)/

41 “About Ball Players,” South-Bend (Indiana) Tribune, August 11, 1897: 6; “Something about Bill Brown,” Evening Leader, December 27, 1897: 3.

42 “Has Played His Last Game and Lost,” Daily Examiner, December 21, 1897: 4.

43 “Something about Bill Brown.”

44 William Brown’s page on Findagrave.com (https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/81324295/william-m-brown)

Full Name

William M. Brown

Born

, 1866 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

December 20, 1897 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.