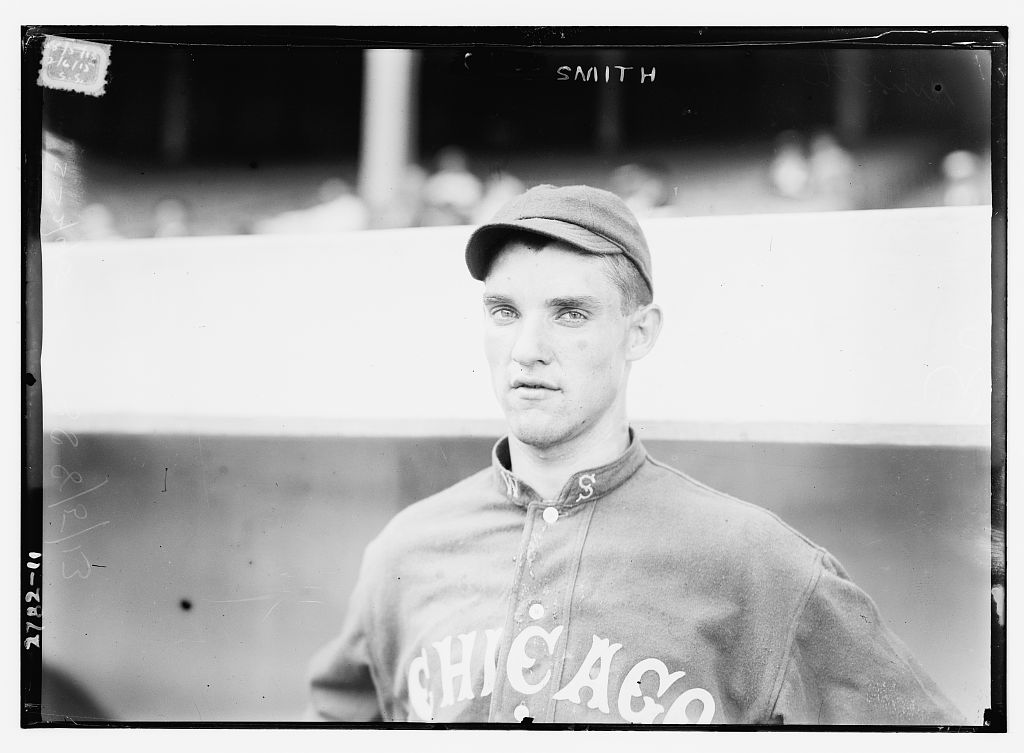

Pop-boy Smith

A teenaged soda vendor at the new Birmingham minor-league ballpark, a low minors “doubleheader” workhorse, a victor over Walter Johnson, and a tragic victim of tuberculosis at 31, Pop-Boy Smith is an enigmatic figure in the Southeast baseball scene from the 1910s and early 1920s.

Clarence Ossie Smith was born on May 23, 1892 in Newport, Tennessee, to William Bruce Smith, a building contractor, and Margaret Cynthia (Dennis) Smith. Clarence was the fourth of seven children in the family, and the only male. The Smith family relocated to Birmingham, Alabama, early in the new century. The 1900 census still shows their residence as in Tennessee.

By the time Clarence was a pre-teen, he’d gravitated towards watching minor-league games of the hometown Barons of the Southern Association. He quickly grew, circa 1903, to be an admirer of Baron and future Chicago White Sox pitcher Frank Smith.1 Clarence started working selling peanuts and later sodas for Baron home games — a so-called “pop-boy” vendor. Barons manager Carlton Molesworth allowed Smith to “chase fungo hits to the outfield and pick up balls which missed the mitts of the catchers.”2 He gained the attention of Barons hurler Earl Fleharty, who taught young Smith about the game, occasionally letting the youngster work out with the team.3

By 1910, Smith was pitching batting practice for the Barons,4 and mastering a quality curve ball. He even listed his occupation in the 1910 census as “ballplayer.” Eventually, Barons catcher Rowdy Elliott vouched that the “youngster had enough ‘stuff’ to win a ball game every now and then and suggested that he be farmed out to a smaller league.”5 Molesworth agreed, so the Barons signed Smith, invited him to spring training in 1911, then sent him east an hour to Class-D Anniston of the Southeastern League on an option.

Smith won his professional debut for Anniston against Selma 6-5 on May 10, striking out 10 Centralites. Barely 19 years old, Smith won the seven-inning second game of a doubleheader 3-1 on June 6 over Gadsden.6 One month into his professional career, Smith was already being labeled “a lifesaver” for the Models.7 Even an opponent’s newspaper acknowledged that “this Anniston Smith has our goat.”8 Less than two weeks later, Smith won his first complete doubleheader, twirling all 14 innings in two seven-inning victories for Anniston, 4-1 and 6-1, over Decatur (Georgia).9 Three days later he finally proved mortal; it was the “first time Smith was unable to save our life.”10

Incredibly, teenager Clarence started seven doubleheaders for Anniston in 1911, earning his first nickname of “Doubleheader” Smith. Newspaper boxscore research shows that he tallied a 24-15 record for the Models, which won the Southeastern League title with a 68-38 mark.11 Smith was selected the top pitcher in the circuit.12 Birmingham exercised their option, and young Pop-Boy was back in Ham Town.

By the summer of 1912, Smith was “the best youngster in the Southern League.”13 In August, “Kid” Smith was second in the Southern Association, just behind Rudy Sommers, with a .765 winning percentage based on a 13-4 mark.14 Before season’s end, Smith was signed by the Chicago White Sox.15 Smith posted a 15-8 record in 1912 for the Barons, which won the league title.

During spring training in Paso Robles, California, the youngster made a solid impression, even with the owner. Charles Comiskey commented that “of the young pitchers, Smith and (George) Mogridge look the best. Smith…has an excellent delivery and remarkable control.”16 Recruit pitchers Smith, Mellie Wolfgang, and outfielder Jimmy Johnston were grouped with the starting squad in most exhibitions.17 Smith pitched a memorable eight innings against the Portland Pacific Coast League team in a March exhibition in Visalia, a central California town, only to be pulled before the ninth inning. The over 1,500 in attendance, including the town sheriff, “demanded” that the star attraction “Big” Ed Walsh, who had been umpiring, pitch to finish the game.18

Clarence broke camp with Chicago in 1913, and “showed some effectiveness”19 in mop-up duty during his major-league debut for the White Sox against the Cleveland Naps on April 19. Smith relieved another Smith, first name Bob, who was making his first major-league appearance (he later resurfaced in the Federal League). Clarence, the “youthful flinger from Birmingham,” went “three rounds…giving the Naps one run, which they didn’t deserve.”20 Smith made three relief appearances in May, sandwiched around his marriage. Smith tied the knot with Lena Elizabeth Lehman from Nashville on May 20.

Smith earned his first start against the Detroit Tigers on May 30 in the first game of a doubleheader, a week after his 21st birthday. It did not go well. As the Detroit Free Press put it, manager Jimmy Callahan “experimented with a recruit pitcher for a few minutes in the opening game.”21 Smith retired the Tigers in order in the first inning. Then, to begin the second inning, he was taunted by Ty Cobb, the Tigers right fielder and cleanup batter, as Smith walked him on four erratic pitches.22 With Cobb continuing to jockey from first base, Smith then allowed a single to Bob Veach, before being pulled by Callahan23 after only five batters of an eventual 3-2 White Sox defeat.

Smith did not take the mound in the entire month of June, before making six relief appearances in July. On July 20, he tossed the final four innings without allowing a hit or walk in a 5-1 defeat to the Washington Senators. Unbeknownst to the fans and Callahan, that was the second game Smith had pitched that Sunday. He had steered the semipro Coulon Athletics to victory earlier that morning, and thought that moonlighting in Sunday leagues was acceptable practice.24 Fortunately for Smith, American League president Ban Johnson showed leniency for the transgression, and didn’t suspend the pitcher, stating that he “was just a youngster, knew no better, and had been forgiven.”25

Smith was also pulled in the second inning of his only other start of the season, on August 6 against the Senators’ Johnson, who pitched one-hit shutout ball over the first four innings to earn his 25th victory. Still, young Smith pitched fairly well for the Pale Hose in 1913, posting a 3.38 ERA in 32 innings of work, without surrendering a single home run. Remarkably, however, the White Sox went 0-15 in Smith’s 15 appearances that season. Forever unfazed from his starting flop, the impetuous Smith stated that his “one ambition is to tie up with Walter Johnson and beat him.”26

Smith began 1914 spring training with the White Sox again on the West Coast. The Alabama lad did not enjoy his second spring in California. After being chided by San Francisco Seals fans during an exhibition matchup, Smith responded by boasting: “No worry, we’ll be back in the United States next week.”27 Smith, however, did not make the trip east with the White Sox, being sold to the Venice Tigers of the Pacific Coast League on March 30,28 while also garnering a new nickname of “U.S.” Smith. Manager Hap Hogan was looking forward to being able to “size him (Smith) up.”29 Smith would be reunited with his former Birmingham mentor Fleharty and Barons catcher Elliott.30

By July, however, Smith was “chafing under his enforced idleness,”31 being left behind on a Venice road trip to Sacramento. Things soured so for Clarence that he engaged in a September dugout fight with teammate Babe Borton, with the reports giving “the decision to Smith.”32 Smith posted a poor 6.42 ERA in only 16 games for Venice in 1914, allowing 71 hits in 47 2/3 innings. After the season, his contract was sold to another PCL team, Portland.33

Smith, however, “wanted more money than Portland was disposed to offer him.”34 Instead, he headed back south, signing with New Orleans for the 1915 season. He fired a 12-inning two-hit shutout on August 17, beating Atlanta, 1-0.35 With a 20-12 record, he paced the Pelicans, who won the Southern Association pennant. His rotation mate was Jim Bagby, who won 19 games and also married Smith’s sister Maggie. After the season, Smith organized and recruited an all-star team to barnstorm against other Southern teams, before setting sail for Cuba in December to battle the Havana Reds and Almendares squads.36

The 1916 season was another solid one for Smith, as he led New Orleans with 23 wins. He threw an early-season no-hitter against Little Rock.37 Pop-Boy beat Burleigh Grimes and Birmingham 2-1 on July 19.38 Another one of Smith’s victories was a 2-0 shutout of Chattanooga on August 8, aided by second baseman Henry “:Cotton” Knaupp’s unassisted triple play.39 Smith earned promotion to the Cleveland Indians in September, being sold for $7,000.40

His Indians debut on September 15 was memorable, and not just from the mound. After tossing shutout eighth and ninth innings, his single in the bottom of the ninth gave the home side a 3-2 win over the Philadelphia A’s, thus “celebrating his return to the big show.”41 By today’s rules, Smith would have earned the victory. Yet according to the rulebook at that time, Ken Penner got his only major-league win (Smith was credited with a save retroactively).42

On September 21, Smith finally had his wish come true. He beat Big Train Johnson and the Senators, 3-2, recording his only win in the majors. Again, the rules in place at that time gave the W to someone who would not be the pitcher of record today. Smith hurled the first nine innings of what turned out to be a 13-inning affair. The Washington Herald wrote that the Senators “were unable to accomplish much against the slick curving of ‘Pop Boy’ Smith, the New Orleans rookie righthander. Smittie bent ’em over in bewildering style for nine rounds.”43

Four days later, Smith pitched fairly well for five innings but fell to another premier opposing pitcher: Babe Ruth, then with Boston. The final score was 2-0.44 Smith’s season concluded with a loss in relief to the White Sox on September 30.

Smith broke camp in 1917 with the Indians, still under manager Lee Fohl, but appeared in only six games, the last being on May 2. He recorded one loss in relief, bringing his final record in the majors to 1-4.

Smith was released on May 7 to New Orleans,45 beginning his third season with the Pelicans, where he posted a 15-13 record. He also claimed a war draft exemption because his wife was dependent on him. The Smiths relocated to the Nashville area, with Pop-Boy co-organizing a community holiday dance charity fundraiser attended by over 300 people.46

Still, Pelicans president A.J. Heinemann tried to unload Smith to Little Rock (and possibly other teams) before the 1918 season, but Travelers owner R.G. Allen was not interested, mainly because of Smith’s reputation as “a troublemaker”47 and being “temperamental.”48 Smith thus started 1918 in the Big Easy for a fourth season. His game-winning single in the bottom of the ninth after 1 2/3 innings of scoreless relief handed New Orleans a 3-2 win over Nashville on May 17.49 Smith beat the same Volunteers twice more, in a doubleheader, just three days later.50 These performances thwarted a proposed trade of Smith to Fort Worth announced earlier that week.51

He later tossed a two-hit masterpiece on June 21, beating 18-year-old rookie Waite Hoyt of Nashville 1-0 in an hour and 10 minutes.52 However, in his last game for New Orleans, Smith walked eight batters with two wild pitches in a 7-4 loss to Birmingham.53 He ended up 8-6 for the Pels in 1918. On June 28, the Southern Association disbanded owing to lack of local interest and the government’s “Work or Fight” order.54

A week later, Smith was in a new time zone, back in the Pacific Coast League, this time with the Salt Lake City Bees. His manager was Walter “Judge” McCredie, who’d been skipper of the Portland team that Smith had spurned back in 1915.55

Smith’s career in Salt Lake spanned exactly two games. He was rocked for eight runs and 12 hits in six innings in his Bees debut on July 5 against Sacramento, part of a 23-5 drubbing. He was then ejected a week later in the third inning against Vernon on July 12 for throwing a ball at an umpire’s face,56 following a dispute over which ball to use. He drew a $250 fine and suspension for the remainder of the season. Just two days later, though, the PCL also shut down because of the war.

Smith was slated to begin 1919 in the PCL again, ostensibly for Portland, where McCredie had moved back as manager.57 Instead, Smith initially reported to Fort Worth of the Texas League.

However, he was too ill to participate. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis and later committed to a sanitarium in Asheville, North Carolina.58 Former Chattanooga manager Billy Smith, now at the helm of Shreveport in the Texas League, visited Clarence. He then penned a letter to other Southern Association teams to help the “penniless” family out financially.59 Multiple teams, including Nashville and Chattanooga, passed the proverbial hat at home games to assist Clarence and his pregnant wife.60 Still, the Smiths welcomed daughter Mary Margaret Smith into the world on October 1, 1919 in Nashville.

Miraculously, Smith recovered in 1920. He announced that he was in “excellent condition, weighs 180 pounds, and believes he can play this season.”61 Smith was signed in March by J.F. Thompson, President of the Gorman, Texas team, to play in the newly formed six-team West Texas League (Class D).62 Former Waco infielder Walt Malmquist was recruited to manage the Buddies, but he elected to play in Canada instead, so Smith was handed his first managerial gig.

Statistics are very scanty for this circuit, but it appears that Smith pitched just on occasion in 1920, his last year as a player. He tossed five innings against Ranger on May 20.63 Exactly one month later, his squad claimed a doubleheader over the same Ranger team, with the player-manager tossing three innings.64 Gorman and Abilene were “fighting for first place,”65 tied at 20-11 early in June. Records through mid-July reveal Smith nominally leading the WTL pitching table with a perfect 3-0 mark. His slugger, left fielder Chink Taylor, was batting .413.66

Gorman did not draw well, however, so, in August, Smith helped engineer a move of the franchise to Sweetwater, Texas.67 He remained as manager and appeared in the first game for the rechristened Syrups.

Later that month, Smith spearheaded a massive player sale, moving four main Sweetwater players, including Taylor (who ended up at .400) and Guy Sturdy (who hit .362), to Texas League teams Fort Worth and Dallas, respectively. Abilene won both halves in the WTL to claim the 1920 pennant. After the season, Smith announced he was opening up a sporting goods store in Sweetwater, with — what else — a soda fountain being installed.68

Before the 1921 season, Smith was spotted in Fort Worth “doing a bit of gumshoeing for his Sweetwater club.”69 Now called the Swatters, Smith’s team again sat near the top of the first-half standings. However, poor league records and management caused mass confusion about who won the first half. Finally, president Walter Morris controversially awarded the first-half pennant to San Angelo, much to the consternation of Smith.70 In response, he wrote a lengthy op-ed on behalf of his aggrieved team.71

Eventually, it was decided to hold a one-game tiebreaker to decide the first-half champ, and Sweetwater won. They then lost to second-half champion Abilene in the finals. Even after the controversy, Smith was strongly considered for the president of the West Texas League following the 1921 season, but he later withdrew his name from consideration.

During the 1922 season, Smith graciously agreed to release his Sweetwater shortstop, Jimmy Flagg, so the latter could become manager of league rival Ranger. Sweetwater finished fourth in the league, which had expanded to eight clubs. Amarillo won the pennant.

After that season, Smith agreed to take over operations of the Sweetwater franchise, assuming that continued local support could be mustered. As it turned out, the West Texas League disbanded, so Smith slid over to manage the new Clovis, New Mexico team in the fledgling Panhandle-Pecos Valley League. The Cubs finished third in the four-team league, which itself folded after the season. In early July, however, W.A. Fuller was summoned from Oklahoma to take over the team.72 The assumption is that health issues led to Smith’s departure.

Clarence Smith succumbed to pulmonary tuberculosis on February 16, 1924, at the young age of 31. He is buried in Elmwood Cemetery in Birmingham, Alabama.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and MyHeritage.com Birth, Draft, Wedding, and Death Records.

Notes

1 Sam Weller, “Sox Pitcher Former Popcorn Vendor; Clarence Smith Has Good Curve Ball,” Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1913: 16.

2 “From Pop Boy to Slab Star is Record of Clarence Smith,” Nashville Banner, August 6, 1912: 14.

3 “From Pop Boy to Slab Star is Record of Clarence Smith.”

4 Nashville Banner, July 18, 1912: 14.

5 “From Pop Boy to Slab Star is Record of Clarence Smith.”

6 “Anniston Wins One and Loses Another,” Anniston (Alabama) Star, June 7, 1911: 6.

7 “Game Notes,” Anniston Star, June 9, 1911: 6.

8 “Game Notes,” Anniston Star, June 10, 1911: 6.

9 “Doubleheader Taken by Anniston’s Models,” Anniston Star, June 21, 1911: 6.

10 “Game Notes” Anniston Star, June 24, 1911: 6.

11 “From Pop Boy to Slab Star is Record of Clarence Smith.”

12 “Southeastern All-Star Clubs,” Chattanooga News, September 14, 1911: 10.

13 “From Pop Boy to Slab Star is Record of Clarence Smith.”

14 Nye, Jack “Rudy Summers Best Pitcher,” Nashville Banner, August 6, 1912: 14.

15 (Cedar Rapids, Iowa) Gazette, August 17, 1912: 8.

16 Handy Andy, “Young Pitchers Promising,” Chicago Tribune, March 26, 1913:13.

17 “Cal Decides on Lineup of Sox for Exhibitions,” Inter Ocean (Chicago) March 4, 1913: 13.

18 Sam Weller, “Visalia Sheriff Must See Walsh,” Chicago Tribune, March 19, 1913: 15.

19 “Naps Lick Sox,” Joliet (Illinois) Evening Herald-News, April 20, 1913: 12.

20 “Smith Goes to Slab,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1913: 29.

21 “Used Youngster,” Detroit Free Press, May 31, 1913: 12.

22 “Cobb’s Chatter Helped Tigers Win,” Montpelier (Vermont) Morning Journal, June 27, 1913: 6.

23 “Lange Succeeds ‘Kid’ Smith,” Chicago Tribune, May 31, 1913: 13.

24 “Smith ‘Unknown’ Hurler,” Indianapolis News, July 22, 1913: 10.

25 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 26, 1913: 7.

26 “Clarkson’s Sox Notes,” Chicago Examiner, August 22, 1913: 7.

27 “Smith’s ‘Exile’ to Be Much Longer,” Lincoln Star, March 31, 1914: 7.

28 “Clarence Smith Sold to Venice by Chicago,” Chattanooga (Tennessee) News, March 31, 1914: 12.

29 San Francisco Examiner, April 7, 1914: 15.

30 “Coast Leaguers Come from South,” St. Louis Star and Times, June 6, 1914: 16.

31 Oakland Tribune, July 31, 1914: 18.

32 Los Angeles Evening Express, September 5, 1914: 12.

33 “Transactions,” Bakersfield Morning Echo, December 3, 1914: 3.

34 Louis Kennedy, “New Bee Hurler Kidded Himself into Nickname,” Salt Lake Telegram, July 5, 1918: 4.

35 “Pop Boy Smith Right,” (Nashville) Tennessean, August 18, 1915: 10.

36 “All-Stars to Play in Cuba,” Oregon Daily Journal (Portland), December 5, 1915: 17.

37 Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock), July 11, 1916: 7.

38 “Pelicans Reap Victory on Two Little Bingles,” Birmingham News, July 21, 1916: 12.

39 https://www.sabrneworleans.com/publications/derbygisclair/pelicanbriefs/8-8-1916.pdf

40 “Clarence Smith Sold to Indians,” Los Angeles Times, September 3, 1918: 61.

41 “Recruit Twirler Wins for Indians,” Akron Beacon Journal, September 16, 1911: 11.

42 “Recruits Win for Indians With Single in Ninth,” (Elmira, New York) Star Gazette, September 16, 1916: 8.

43 “Indians Land Final Game with Griffmen” Washington Herald, September 22, 1916: 8.

44 “Indians Shut Out by Red Sox,” Boston Globe, September 25, 1916: 7.

45 “Baseball Notes,” Indianapolis News May 7, 1917: 12.

46 “Dance Given for Charity a Success,” Nashville Banner, December 24, 1917: 5.

47 “Two Pel Players Put on Market,” Daily Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock) February 14, 1918: 10.

48 “Knaupp Will Not Join Travelers,” Arkansas Democrat (Little Rock) February 23, 1918: 13.

49 “Smith’s Hit Defeats Vols,” Nashville Banner, May 18, 1918: 8.

50 “‘Popboy’ Smith, in Iron Man Role, Downs Ellamites in Both Games, 2 to 1 and 2 to 0,” (Nashville) Tennessean, May 20, 1918: 12.

51 A. M. Keisker, “Kike’s Komment” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 20, 1918: 6.

52 “Hoyt Loses Great Duel to Pop Smith,” Tennessean, June 22, 1918: 10.

53 “’Pop Boy’ Smith Easy Picking for Moley’s Men,” Chattanooga Daily Times, June 27, 1918: 8.

54 Celia Storey, Celia “Old News” 100 Years Ago in Little Rock, Baseball Halted Patriotically,” Arkansas Democrat Gazette, June 25, 2018: online. https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2018/jun/25/baseball-halts-patriotically-20180625/

55 Louis Kennedy, “New Bee Hurler Kidded Himself into Nickname,” Salt Lake Telegram, July 5, 1918: 4.

56 Vancouver Sun (Vanocouver, British Columbia), July 13, 1918: 11.

57 “Same Old Story,” Arkansas Democrat, March 28, 1919: 15.

58 “Neat Sum for ‘Pop Boy’ Smith,” Nashville Banner, June 16, 1919: 12.

59 “Fans Will Get a Chance Today to Aid Unlucky ‘Pop Boy’ Smith,” Chattanooga Daily Times, June 8, 1919: 22.

60 “Neat Sum for ‘Pop Boy’ Smith,” Nashville Banner June 16, 1919: 12.

61 Billy Bee, “Oil Belt Club Has Players in ‘Training Camp’,” Fort Wort Star-Telegram, March 16, 1920: 16.

62 “West Texas League Starts,” Houston Post, April 30, 1920: 11.

63 “Gorman 12, Ranger 8,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 21, 1920: 8.

64 “Gorman Takes Two,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram June 21, 1920: 13.

65 Billy Bee, “Buzzin’ Around with Billy Bee,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram June 5, 1920: 7.

66 “Taylor, of Gorman, Leading West Texas League Batter; Swats .413; 18 Hit Over .300,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 25, 1920: 23.

67 “Syrups 6, Ranger 1,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, August 9, 1920: 10.

68 “’Pop Boy’ Smith is Now Business Man,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, December 30, 1920: 3.

69 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, March 8, 1921: 15.

70 “Prexy Morris Gives Pennant to San Angelo,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 6, 1921: 12.

71 “’Pop Boy’ Smith Explains Why Swatters Won’t Play Game Against San Angelo,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 6, 1921: 12.

72 Woodward (Oklahoma) Democrat, July 19, 1923: 1.

Full Name

Clarence Ossie Smith

Born

May 23, 1892 at Newport, TN (USA)

Died

February 16, 1924 at Sweetwater, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.