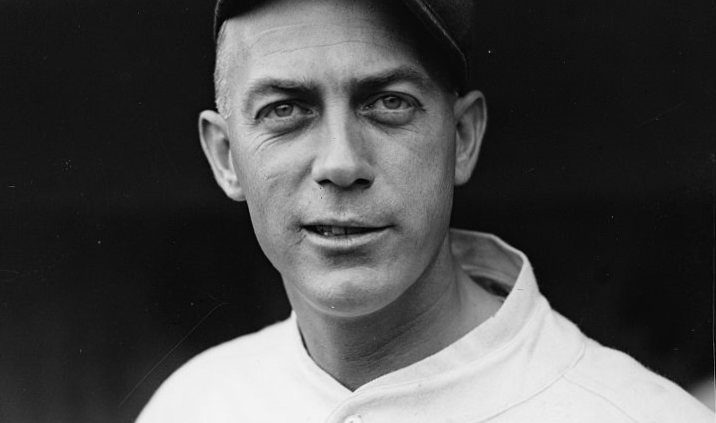

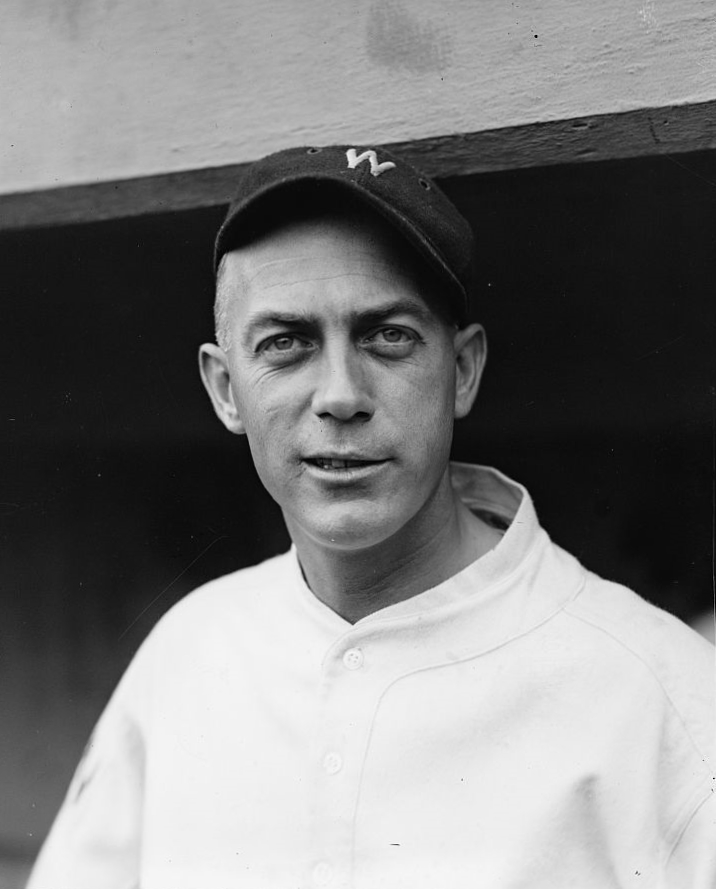

George Mogridge

The tall, lanky, left-handed pitcher George Mogridge is best remembered today as the answer to a trivia question: Who pitched the first no-hitter in New York Yankees history? Yes, the answer is George Mogridge, on April 24, 1917, against the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park. During his time in the major leagues from 1911 to 1927, however, Mogridge was known for more than just that one memorable pitching performance. No less an eminence than Babe Ruth, lamenting the trade that sent Mogridge from the Yankees to the Washington Senators, called him the “best left-hander in the league.”1 Hall of Fame center fielder Tris Speaker echoed Ruth’s sentiment: “George Mogridge is not only the best southpaw in this league, but also the best pitcher.”2 This “best pitcher in the league” never won more than 18 games in a season, and finished his career with a 132-133 record, but he helped the Washington Senators become pennant contenders in the 1920s and was a key figure in their World Series victory in 1924.

The tall, lanky, left-handed pitcher George Mogridge is best remembered today as the answer to a trivia question: Who pitched the first no-hitter in New York Yankees history? Yes, the answer is George Mogridge, on April 24, 1917, against the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park. During his time in the major leagues from 1911 to 1927, however, Mogridge was known for more than just that one memorable pitching performance. No less an eminence than Babe Ruth, lamenting the trade that sent Mogridge from the Yankees to the Washington Senators, called him the “best left-hander in the league.”1 Hall of Fame center fielder Tris Speaker echoed Ruth’s sentiment: “George Mogridge is not only the best southpaw in this league, but also the best pitcher.”2 This “best pitcher in the league” never won more than 18 games in a season, and finished his career with a 132-133 record, but he helped the Washington Senators become pennant contenders in the 1920s and was a key figure in their World Series victory in 1924.

George Anthony Mogridge was born on February 18, 1889, in Rochester, New York, to Charles Mogridge and the former Theresa J. Nobles. George’s grandfather had emigrated from England and settled as a farmer in the area. George had an older brother, Charles Joseph Mogridge. He attended Holy Family High School in Rochester and starred as a baseball player on sandlots in and around the city. After high school, he pitched for local semi-pro teams and for two years with the University of Rochester. In 1912, Mogridge told Chicago Tribune reporter Sam Weller that he took a course in penmanship at the college, so that he could be eligible to pitch for the school.3 During this period, Mogridge earned a living by working as a plumber4 and roofer.

In the spring of 1911, a catcher friend received a contract from the Galesburg, Illinois Pavers of the Central Association. He invited Mogridge to go along with him. Having $500 in the bank and nothing to hold him in Rochester for the moment, Mogridge agreed to go along. The day after he arrived, he had a chance to pitch for the Pavers, won the game, and became a regular part of the rotation. In 33 games he had a 20-9 record. His pitching attracted the attention of Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, who sent his manager, Hugh Duffy, on the 200-mile road trip to see him. Duffy was impressed and brought Mogridge back to Chicago with him.5

The 22-year-old Mogridge made his major league debut on August 17, 1911, in relief against the world champion Philadelphia Athletics. He impressed by working two shutout innings in a 5-1 White Sox loss. The next day, Mogridge was called on again; this time with the bases loaded, two out and the A’s star second baseman, Eddie Collins, at the plate. With the count 2-2, Mogridge unleashed a wicked curve ball that catcher Billy Sullivan and Chicago Tribune reporter I. E. Sanborn both swore cut right across the plate, but umpire Doc Parker called it a ball.6 Collins singled to center on the next pitch to score two. Mogridge followed that with two more shutout innings and the Sox eventually won the game for Big Ed Walsh, who relieved Mogridge in the seventh inning, with two runs in the eighth, 7-5. Mogridge appeared in only two more games that fall, having been worn down by pitching 33 games and 247 innings at Galesburg before coming to the White Sox.

Mogridge started the 1912 season on the White Sox staff, splitting his time between starting and relieving. On May 15, he beat the Cleveland Naps 2-1, scattering nine hits in a complete game, and defeated the New York Highlanders on June 9 with a five-hitter, again by the score of 2-1. By July, however, it was determined that Mogridge was not getting enough chances to pitch with the big club, and he was sold to the Lincoln, Nebraska, Railsplitters of the Western League. Thus began a three-year odyssey of stellar minor league pitching before Mogridge would return to the major leagues.

Mogridge recorded an 8-5 record in 14 games at Lincoln in 1912 and began 1913 in spring training with the White Sox in Oakland, California, where one scribe called him the “best of the youngsters” with a “beautiful curve” and a certain “coolness” on the mound.7 The White Sox farmed Mogridge out to the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association for the 1913 season, where he compiled a 13-10 record in 36 games. He began 1914 with the Millers again but was acquired early in the season by the Des Moines Boosters of the Western League, where he established himself as a dependable pitcher and a popular player. Always a good hitter, he had played the outfield for Galesburg when he wasn’t pitching, Mogridge hit two home runs for the Boosters in a game on May 28, 1914. He finished the year with a .333 batting average, third best in the league. No official account of his pitching statistics exists for 1914, but from newspaper accounts we can estimate that he compiled a 17-9 record with four shutouts for the season.8

Mogridge married the former Clara A. Mitchell, whom he had met while she was working in a Rochester bakery, in or about 1914. Their son, George J, was born in Des Moines in 1915 while Mogridge was pitching for the Des Moines club.

In 1915, Mogridge was Des Moines’ star southpaw with a 24-11 record and impressive 1.93 ERA in 307+ innings in 42 appearances. The Yankees, in desperate need of left-handed pitching, sent scout Duke Farrell to purchase Mogridge’s contract. Boosters manager Frank Isbell agreed to the sale on June 27 but would not release his ace pitcher until after Mogridge helped the Boosters win the Western League title. Finally, in late August with the title assured, Isbell released him to the Yankees.9

Mogridge made his debut with the Yankees on September 4 in the ninth inning of a tie game with the Washington Senators and promptly yielded the walk-off winning run on a Rip Williams single. In five starting assignments after that, however, Mogridge pitched well. He was beaten by a Ty Cobb two-run single in his home debut on September 14, but then threw a complete game shutout over the St, Louis Browns at the Polo Grounds on September 23. At 26 years of age, Mogridge filled a Yankee need for a left-handed starter and he was finally in the major leagues to stay.

A “sprained arm” delayed Mogridge’s start to the 1916 season (he did not appear in a game until May 5) and prevented him from taking a regular turn in the rotation at various times during the year.10 In 30 games, including 21 starts, he compiled a 6-12 record with a very respectable 2.31 ERA for the fourth-place Yankees. In 1917, the Yankees slipped to seventh place and Mogridge’s effectiveness slipped with them. While his record improved a bit to 9-11, his ERA rose to 2.98 and his ERA+ was just 90. The season did produce one major highlight, however, the no-hitter at Fenway Park against the World Champion Red Sox. The game was a tense affair throughout. With Mogridge squaring off against Boston left-hander Dutch Leonard, the contest was scoreless into the sixth. In the top of that inning, Yankee third baseman Angel Aragon doubled and scored when Lee Magee singled. Boston tied the game in the seventh. Sox player/manager Jack Barry drew a walk. Del Gainer than grounded to second baseman Fritz Maisel who threw to shortstop Roger Peckinpaugh at second base. Peckinpaugh muffed the throw for an error and runners were on first and second. Yankee manager Wild Bill Donovan ordered that Tillie Walker be intentionally walked. With the bases loaded, Barry called on Jimmy Walsh to pinch hit for Larry Gardner. Walsh launched a long fly to right fielder Frank Gilhooley, which scored Barry with the tying run. Mogridge then got Everett Scott to ground out to third.

In the ninth, the Yankees managed to get the go-ahead run. Peckinpaugh singled, stole second and moved to third when catcher Hick Cady’s throw went into the outfield. Les Nunamaker grounded to third, scoring Peckinpaugh. In the bottom of the ninth, Mogridge retired the first two batters easily and with two out, induced an easy ground ball to second from Duffy Lewis. Maisel fumbled the ball, however, allowing Lewis to reach first base and forcing Mogridge to face the dangerous Walker. With the game and the no-hitter on the line, Mogridge got Walker to ground into a force out.11

After the game Mogridge told Grantland Rice, “Now there is a world of rivalry between the Red Sox and the Yankees, and my first thought was to win the ballgame. I never realized [I had a no-hitter] until [manager] Bill Donovan came out [in the eighth] and said, ‘It would be a crime to lose this game for they haven’t gotten a blow off you yet.’ It was not until the last of the ninth that I suddenly realized I’d like to have at least one no-hit game in my kit – and especially a no-hit affair against the World Champs. It was not until two men were out that I got my shock. I had only one man to get and he tapped an easy one for an easy out. An error resulted, and with such a fine chance gone it occurred to me the next man up [Tillie Walker] was about due. It generally happens that way, leave an opening, and they nail you. That was the first nervousness I felt. I knew the side should be out and I should be on the way to the clubhouse with my no-hit game sewed up. But this time the upset didn’t work out.”12

Under new manager Miller Huggins, Mogridge had his best season as a Yankee in 1918, compiling a 16-13 record with a 2.19 ERA. Used as a reliever and spot starter, he led the league in appearances with 45, saves with seven and games finished with 23. On May 24, he pitched 11 innings of shutout relief against the Cleveland Indians, only to lose the game in the 19th on a Smoky Joe Wood solo home run. When given the chance to start, he often responded well. On June 24, he beat the Red Sox, 3-2, on a three-hitter. Mogridge had become a real Red Sox nemesis, beating the pennant winners six times in six starts without a defeat.

Mogridge filled the same reliever/spot starter role for the 1919 third-place Yankees. Despite a mediocre record, he held out in the spring of 1920, but his pitching declined further. With the addition of Babe Ruth, the Yankees improved to 95-59, but Mogridge contributed little, going 5-9 with a 4.31 ERA. After the season, rumors that Miller Huggins was looking to trade the 32-year-old pitcher circulated in the New York press. Speculation was that George might end up in Washington with Clark Griffith’s Senators. The trade was made On December 31. Mogridge and outfielder Duffy Lewis were sent to the Washington Senators for much travelled, bad boy outfielder Bobby “Braggo” Roth. The trade turned out to be a good one for the Senators. Roth played little for the Yankees in what would be his final season in the majors and, while Lewis did not contribute much to the Senators, Mogridge became a mainstay of the Washington staff for years to come.

With Washington, Mogridge became the consistent winner he had never been with the Yankees. Used almost exclusively as a starter, he had a banner year in 1921, winning 18, losing 14, with a respectable 3.00 ERA. He was Washington’s top pitcher, outpointing even the great Walter Johnson, who was 17-14 with a 3.53 ERA that year. In his first start against the Yankees in the second game of a doubleheader on May 30, Mogridge outdueled the old spitballer Jack Quinn, 1-0, allowing only two hits. On July 1, also in the second game of a doubleheader, Mogridge pitched a 12-inning, three-hit shutout to best Bob Hasty and the Philadelphia A’s, 1-0.

In 1922, Mogridge again won 18 games, losing 13. On April 12 he was the opening day starter for the Senators, receiving the ceremonial first pitch from President Warren G. Harding. That day, he beat the Yankees, 6-5. On August 3, he beat the White Sox, 2-0, at Comiskey Park, helping his own cause with the only home run of his major league career. Early in 1923, Mogridge was hit on his pitching hand by a line drive off the bat of the Yankees’ Joe Dugan. The blow broke his thumb. While it was predicted he would be lost for at least a month, he returned to the mound three weeks later, but was hit hard in his first three starts after the injury. He eventually recovered to have another solid season: 13-13 with a 3.11 ERA. Perhaps the best game he pitched that season resulted in a loss. On July 3, he faced off against Bullet Joe Bush of the Yankees at the brand-new Yankee Stadium. The game was scoreless until the bottom of the eighth when Bush, always a fine hitter, bounced a drive over the fence for a ground-rule home run. The Senators tied the game in the ninth when Patsy Gharrity singled and scored on a Joe Evans triple. Evans was cut down at the plate trying to score on a relay throw from Babe Ruth to catcher Fred Hofman. The game rolled into extra innings tied at one with neither pitcher yielding, until Ruth led off in the bottom of the 15th and beat Mogridge by smashing the first pitch he saw into the right field seats for the game-winning home run.

Nineteen twenty-four was a banner year for the Washington Senators. They captured their first- ever American League pennant and World Championship. Hall of Famer Walter Johnson led the team with a 23-7 record, but the 34-year-old Mogridge made a significant contribution, going 16-11 in 30 starts. On August 14 he pitched a two-hit shutout beating Joe Shaute and the Cleveland Indians, 1-0. However, he struggled somewhat during the season with shoulder problems and was not as effective down the stretch as the Senators fought to hold off the Yankees and Detroit Tigers in the pennant race. Speculation was that Mogridge was “temporarily burned out”13 by the stretch run and would not be used at all in the World Series against the National League Champion New York Giants.

Manager Bucky Harris, however, chose him to start Game Four, with the Senators behind in the Series two games to one. Mogridge, described by one reporter as “a lean and hungry Cassius on the mound,”14 responded with 7 1/3 innings of three-hit, three-run (two earned) baseball in leading the Senators to a much needed 7-3 victory.

In Game Seven, with the series on the line, Mogridge again played a key role. Fearing left-handed hitting rookie first baseman Bill Terry more than any other Giants’ hitter (Terry was batting .500 for the Series coming into the game), Harris started right-hander Curly Ogden. The plan was to get Giants manager John McGraw to start Terry, who at this point of his career was a platoon player, so that Harris could counter with the lefty Mogridge in the first inning. The plan worked. Ogden pitched to only two batters, Freddie Lindstrom, who struck out, and Frankie Frisch, who walked. When left-handed hitting Ross Youngs strode to the plate, in came Mogridge. Mogridge pitched four 2/3 effective innings and retired Terry twice on a groundball and strikeout. With Terry scheduled to face Mogridge a third time, McGraw sent up right-hander Irish Meusel to pinch hit. Harris then countered with right-handed reliever Firpo Marberry. The ploy had worked. Terry was not a factor in the game and was on the bench by the sixth inning of a game that would go on for twelve. Washington won the game and the series when they got four innings of shutout relief from Johnson and a walk-off RBI double from rookie Earl McNeely in the bottom of the twelfth.

In 1925 the aging Mogridge was ineffective in five starts for the Senators. On June 18 he was traded along with catcher Pinky Hargrave to the St. Louis Browns for catcher Hank Severeid. Mogridge was 1-1 in two starts for the Browns and then was shut down for the season, his pitching arm placed in a plaster cast after a diagnosis of “synovitis.”15 The next spring, the Browns traded Mogridge to the Yankees for catcher Wally Schang, Miller Huggins owed the St. Paul club of the American Association a pitcher due to an earlier deal, and he thought Mogridge would be just the man to send to the minor league club. But Mogridge, as a 10-year major league veteran, exercised his right to refuse to be sent to the minors and signed with the Boston Braves instead.16

Mogridge started the season in the starting rotation for the Braves but was largely ineffective. He worked out of the bullpen for the most part for the remainder of the year with mixed results. Back with the Braves in 1927, he pitched effectively in a relief role, until he was granted his release in July to become the manager of the Rochester Tribe of the International League. Braves’ manager Dave Bancroft said he did not want to stand in Mogridge’s way if he had an opportunity for “betterment.”17 In his final major league game, Mogridge lost to the Giants, 4-1, on July 2.

Mogridge was returning to his hometown with a three-year $30,000 contract as a player/manager for the Rochester club. He joined the team on July 4 and pitched in relief for them for the first time on July 8. Rochester was pleased to have the hometown boy return. They held a “George Mogridge Day” on August 22. On his “Day,” Mogridge pitched five innings and was the winning pitcher as his Rochester team beat the Newark Bears, 7-3. In January 1928, however, the Rochester team was sold to the St. Louis Cardinals. The Cardinals decided they wanted their own man, Billy Southworth, to manage the team, and Mogridge was out of a job. He reached a financial settlement with the Cardinals and tried to return to the Braves as a pitcher, but he found little interest from his former team. There was some lingering resentment in the Braves front office about the way Mogridge had left the team in the middle of the 1927 season.18 In May, Mogridge announced his retirement from baseball and opened a restaurant just outside Rochester, called the Mogridge Inn.19

Mogridge’s restaurant became famous for its fried chicken and for flaunting prohibition and gambling laws.20 The manager of the inn was reported to have paid fines for these violations at various times.21 The inn also featured a baseball field, which became the site of semi-pro games. Mogridge both managed and played for these teams in his retirement. During the 1930s, he led the organization of the regional “Mogridge League,” a semi-pro league which featured eight teams divided into Western and Eastern divisions. When a fire destroyed the Mogridge Inn in 1934, George opened a sporting goods store in Rochester. The Mogridge Sport Shop lasted until 1942, at which point George went to work for the Weathermaster Company selling storm doors. He remained with that company until his retirement in 1960.22 Mogridge spent much of his leisure time fishing. He owned a fishing cottage on the Bay of Quinte in Ontario, Canada.23

In 1936, Mogridge gave a remarkable interview to reporter Al C. Weber of the Rochester Times Union, concerning the use of foreign substances on baseballs. Apocryphal or not (Weber never quotes Mogridge), it highlights the ongoing controversy of “loading up” the baseball. In 1920, the American League in banning the spitball, also banned the use of resin, which was used to throw a “shine ball.”24 As Weber tells the story, Mogridge had always used resin to get a better grip on his big breaking curveball. To circumvent the new rule, George recalled an old trick he had learned while pitching in the minors. A pitcher can hide resin and keep it dry by dusting it on the inside of the bill of the baseball cap. Mogridge did this for the rest of his American League career, loading up his fingers to get the bite he needed for his pitches. Over the years, although hitters complained and umpires searched his clothing and gloves repeatedly, no one ever discovered where the resin was hidden.25 The American League lifted the resin ban in 1926.26

George Mogridge died of a heart attack on March 4, 1962. He was 73 years old. Mogridge is buried in Holy Sepulcher Cemetery in Rochester.27

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited below, the author consulted baseballreference.com and retrosheet.com.

Notes

1 Babe Ruth, “Ruth Sure Yankees Will Win; To Lead Cleveland by 5 Games,” Washington Times, May 27, 1921: 18.

2 “Speaker Likes Him,” Washington Times, August 15, 1921: 13.

3 Sam Weller, “George Mogridge Starts Baseball Career as a Student in Writing,” Chicago Tribune, February 29, 1912: 9.

4 U.S. Federal Census, 1910.

5 Weller.

6 I. E. Sanborn, “White Sox Army Whips Mackmen,” Chicago Tribune, August 19, 1911: 9.

7 Home Run, “White Sox to Be Stronger All Around, Says Callahan,” (Chicago) Inter-Ocean, March 13, 1913: 27.

8 These numbers were compiled from accounts in the Des Moines Register.

9 Sec Taylor, “Mogridge Goes to New York Yankees,” Des Moines Register, June 28, 1915: 6.

10 “Six Best Yankees Injured in Action,” New York Tribune, July 19, 1916: 13.

11 “Mogridge Turns in First No-Hit Game by a Yankee,” (New York) Sun, April 25, 1917: 13.

12 Grantland Rice, “The Sportlight,” New York Tribune, April 29, 1917: 18. As it turned out Mogridge’s gem was one of a spate of no-hitters in the first weeks of the 1917 season. Five no-hitters were pitched from opening day on April 11 through May 6 (Eddie Cicotte, Mogridge, Fred Toney, Ernie Koob, Bob Groom). This is the shortest span ever for five no-hitters, but in 2021 six no-hitters were thrown between April 9 and May 19 (Joe Musgrove, Carlos Rondon, John Means, Wade Miley, Spencer Turnbull, Corey Kluber).

13 John B. Keller, “Harris Confident of Winning World Title: Players Start Priming for Big Games,” (Washington, DC) Evening Star, October 1, 1924: 26.

14 “Knots Series Again,” Kansas City Times, October 8, 1924: 14.

15 Mogridge Has Arm in Plaster Cast, Bush Also Ailing,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 5, 1925: 11.

16 “Huggins Accused of Pulling a Boner,” Miami Herald, March 18, 1926: 33.

17 “Mogridge Said to Be Slated for Rochester,” Boston Globe, June 25, 1927: 8.

18 George Mogridge is Free Agent; Dickers with Boston Club,” (Rochester) Democrat and Chronicle, March 2, 1928: 10.

19 “Former Rochester Sandlotters Making Good with League Ball Clubs,” Democrat and Chronicle, May 2, 1928: 9.

20 Same as above

21 “Big Liquor Haul Made in Culver Road,” Democrat and Chronicle, December 31, 1929: 14.

22 “George A. Mogridge Dies: Played in World Series,” Democrat and Chronicle, March 5, 1962: 21.

23 Same as above.

24 W. J. Macbeth, “American league Legislates Against Use of Spitball Pitching After 1920 Season, New York Tribune, February 10, 1920: 12.

25 Al C. Weber, “Page Sherlock Holmes,” Rochester Times Union, March 28, 1936: 20.

26 Richard Vidner, “All Circuits Lift Ban on Resin Ball,” New York Times, January 30, 1926: 11.

27 George A. Mogridge Dies: Played in World Series,” above.

Full Name

George Anthony Mogridge

Born

February 18, 1889 at Rochester, NY (USA)

Died

March 4, 1962 at Rochester, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.