Dean Stone

Left-hander Dean Stone spent parts of eight seasons in the major leagues, pitching for six different teams and compiling a career record of 29-39 with a 4.47 earned run average in 686 innings. His most celebrated moment was almost certainly his being the winning pitcher of the 1954 All-Star Game without officially facing even one batter.

Left-hander Dean Stone spent parts of eight seasons in the major leagues, pitching for six different teams and compiling a career record of 29-39 with a 4.47 earned run average in 686 innings. His most celebrated moment was almost certainly his being the winning pitcher of the 1954 All-Star Game without officially facing even one batter.

Stone, who had replaced the injured Ferris Fain on the AL team, actually did pitch to a batter in that game before 69,751 fans at Cleveland Stadium on July 13 – Duke Snider of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The score was 7-7 after five innings. The AL took an 8-7 lead in the bottom of the sixth. In the top of the eighth, Willie Mays singled and pinch-hitter Gus Bell homered, tipping the balance to 9-8 in favor of the National League. With two outs, an error and a single put Red Schoendienst on third base and Alvin Dark on first. AL manager Casey Stengel called in the southpaw Stone, the sixth pitcher he’d used, to pitch to Duke Snider. Stone threw his warmup pitches, while third-base coach Leo Durocher whispered to Schoendienst at third.

“He’s just a kid,” Durocher told Schoendienst. “He might balk. I’ll draw a marker down the line and you come that far, maybe on the first pitch or two. Then if he is still watching Dark on first, go the next time.”1 That’s just what happened. Stone was keeping a watchful eye on Dark before each of his first two pitches. Just before the third pitch, Schoendienst took off for home plate, hoping to steal an insurance run. But Yogi Berra made the tag, and he was called out by plate umpire Bill Stewart.2 Inning over. Snider was left standing at the plate. Both Durocher and first-base coach Charlie Grimm protested that Stone had balked, by hurrying his pitch and not coming to a set position before he pitched. The argument was to no avail.

With one out in the bottom of the eighth, Larry Doby pinch-hit for Stone and homered to tie the score. Mickey Mantle singled, Berra singled, and Al Rosen drew a walk. Mickey Vernon struck out, but Nellie Fox singled to center, driving in both Mantle and Berra and the American League had an 11-9 lead. Virgil Trucks pitched a scoreless top of the ninth and got the save, while Stone earned the win. (It was the highest-scoring midseason classic before the raucous 13-8 affair in Denver’s Coors Field in 1998.) The victory marked the only time in All-Star history in which a pitcher was awarded a win without retiring a batter. Moreover, Stone joined four-time All-Star righty Dutch Leonard as the only Senators pitchers to ever win the midsummer classic.

Darragh Dean Stone was born in Moline, Illinois, on September 1, 1930. He was the middle child of five who were born to Lyle Alfred and Frances Elizabeth (Goddard) Stone. The Stones lived in Hampton, Illinois. Lyle Stone worked as a steam fitter at a farm implement factory. Frances and Lyle were both Illinois natives apparently willing to give unusual names to a couple of their children: Hilbert, Lynn, Darragh, Paul, and Allen.

Where Dean grew up, softball was common but baseball was not. His four brothers pressed him to pitch in softball, but he said he could never get used to underhand pitching. “I just couldn’t throw the legal way and so I couldn’t pitch. So they moved me to first base on the softball team and that’s where I stayed.”3

When the family moved to a farm in East Moline, Dean went to United Township High School. He went out for the baseball team as a sophomore and was finally able to throw overhand. “Before that, I had never seen a baseball game of any kind.”4

He had been encouraged by his father, Lyle, reportedly a right-handed pitcher who “once turned down an offer from the Cubs and has regretted it ever since.”5 Dean’s mother, however, remembered Lyle as a semipro second baseman, and Lyle’s father as a pitcher or catcher of some local renown.6

Dean was a left-hander who grew to be 6-foot-4, listed at 205 pounds. He first signed with the Chicago Cubs sometime before the 1949 season, and pitched two innings on May 3 for the defending champion Clinton Steers of the Class-C Central Association in an 18-6 loss at Burlington. Stone had an early season “hand issue” and, after three weeks, was released.

Back home in June, Stone “walked, cap in hand, into a tryout school conducted by Washington scouts Jack Rossiter and the late Mike Martin, in Streater, Illinois. They liked Dean’s determination and delivery and signed him to a Class D contract.”7 He reported to the Orlando Senators of the Florida State League. There he got to work in eight games; he was 1-4 with a 6.08 ERA.

On November 29, 1949, the beanpole pitcher with an uncanny resemblance to future Democratic presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson married high school classmate Margaret “Peggy” Scott.

In 1950, Stone returned to Orlando and saw work in 24 games. His record was 6-7 with a 4.47 ERA. He was moved up a class in 1951, to the Class-C Erie Sailors in the Middle Atlantic League. There he worked even more innings and games, and produced an 8-3 record with an improved 4.10 ERA. But his struggle with control—324 walks over his first 321 career innings, including a league-leading 158 with Erie—did little to endear him to the organization. The coaches continued to work to tame his lively fastball and their patience paid off in 1952. He went to spring training with the Senators for a “long look” but was returned to Chattanooga on March 24.8 Stone spent most of the year with the Charlotte Hornets in the Class-B Tri-State League (17-10, 3.18) – and worked one inning in one game for Chattanooga in Double A. On May 28 he pitched a no-hitter – with 14 strikeouts (including seven in succession) – against Gastonia, with only one ball being hit out of the infield. During an August tour of the farms, Senators GM Calvin Griffith cited Stone among the franchise’s most promising pitchers. He threw another no-hitter later in the year, on September 7 against Anderson in the playoffs. Teammate Bob Danielson had also thrown a no-hitter in the playoffs just days earlier.

“Stone will make it to the majors . . . in a large way,” Senators farm director Ossie Bluege predicted before the start of 1953 spring training. “Even allowing for the fact he was pitching . . . in a B league last season . . . I don’t see how he can miss.”9 Stone’s strong Grapefruit League play appeared to bolster Bluege’s predictions before two challenging appearances at the end of March caused the Senators to reconsider. Stone opened the season with Washington, but he saw no action and on May 12 was optioned to Chattanooga. He was 8-10 with a 3.33 ERA for the offensively-challenged Lookouts. He was recalled to Washington in September and got a taste of big-league ball. His debut came in relief against the Tigers on September 13. The score was 6-0 with a runner on first base and nobody out when he entered the game. The inherited runner scored and he gave up two runs of his own before getting out of the inning. He finished the game, working 4 2/3 innings, and was charged with three runs. He pitched a hitless inning on September 20 and then was given a start on September 26. He gave up five runs in three innings, and was replaced. He was 0-1, 8.31.

He asked for, but was denied, “permission to pitch winter ball below the border.”10

During spring training 1954, manager Bucky Harris said he believed Stone had shown that he was good at pitching himself out of trouble. “I think Stone has matured to the point where he’ll give us a lot of help.”11 Indeed he did. He won his first four decisions and was 6-1 at the end of June, including a superb five-inning no-run, two-hit performance against the Philadelphia Athletics on May 23 to register his first major-league win. (A poor career hitter, Stone aided his cause with an eighth-inning two-run triple; four months later he would connect for his only major-league homer.) Stone’s emergence proved pivotal in providing an instant replacement for slumping Senators starters Spec Shea and Connie Marrero.

The Washington Post’s Bob Addie explained that the 23-year-old left-hander’s sudden success may have been driven by necessity:

If it weren’t for a broken-down car, Dean Stone, the Nats’ newest pitching sensation, may not have been with Washington this season. Here’s the way it happened: Dean drove to the Nats’ Florida training camp from his home in Illinois. On the way, his car had a cracked block. I recall Stone sitting around the lobby of the Nats’ hotel in Orlando the first day and recounting some of his woes. ‘That car is going to cost money to fix,’ he said. ‘I’ve got to make good now.’ There have been many athletes who have become great when prodded by financial necessity. Many baseball and fight managers will tell you that’s the best kind of athlete—a hungry one. Stone, incidentally, still looks the part. He appears to be a fugitive from a good meal, but who can be superior when contemplating his fine record this far?12

This was the year he was named to the All-Star squad and won the game.

He lost four games in August, but it was for lack of run support; the offense was shut out twice and scored only one run in another game. On September 11 he delivered his first major-league shutout with a 5-0 win against the Baltimore Orioles. Six days later Stone followed with a three-hit whitewash of the Boston Red Sox. The twin blankings contributed to a string of 32⅔ consecutive innings in which the lefty did not surrender an earned run. By season’s end, he was 12-10 with a 3.32 earned run average. Stone finished among the club leaders in nearly every pitching category; his inclusion in the rotation marked the first time in major-league history that four left-handed hurlers made up a significant portion of a club’s rotation (20 or more starts each—a feat matched only by the White Sox in 2013 and 2015). In a deep rookie class that included future HOF outfielder Al Kaline and 20-game winner Bob Grim,13 Tigers broadcaster and former All-Star hurler Dizzy Trout selected Stone among the most promising. Many others appear to have agreed with Trout as, throughout the offseason, the Senators were inundated with trade offers for Stone. The queries ended only after Griffith announced the lefty as untouchable—the only rookie among the four so classified on the Senators roster. It was by far the best year he would ever have in the majors.

Stone’s 1955 season saw him post a 6-13 record (an astonishing seven of his losses came in games the Senators were shut out), though his ERA of 4.15 shows he wasn’t pitching quite as well. Moreover, the control problems seemingly once conquered resurfaced as he placed among the league leaders in walks (114) and wild pitches (9). Despite the disappointing season, Stone remained widely sought after by other clubs. The Senators offered additional compensation if he would forgo his offseason job as a switchman for the Rock Island Railroad to rest for the following season.

After his rookie season Stone rarely did much with the bat to help his cause. In 60 plate appearances in 1955, he had two hits. His career batting average was .088, with 12 RBIs (nine of them in 1954 and only three in the other years put together). He was a good fielding pitcher who didn’t make an error in any of his first three seasons – though he then made five in 1956. He only made two more errors in his career.

Measured by earned run average, 1956 was Stone’s worst season. He was a holdout in spring training because he’d been asked to take a pay cut from $10,000 to $8,000, an unfortunate way to start the year.14 Matters were resolved, with him reportedly accepting $9,000.15 He worked in 41 games, 21 of them starts, but rarely pitched long, recording only 132 innings. He was 5-7 with a 6.27 ERA for the year. A glimmer of hope surfaced on July 29 when he was one strike away from his fourth career shutout before a Bob Kennedy home run forced Stone to settle for a 4-1 complete game win against the Tigers. He’d started the season with a complete-game 8-4 win, with only two of the runs being earned, but throughout the season had a mixture of starts and relief appearances and had only one other complete game all year.

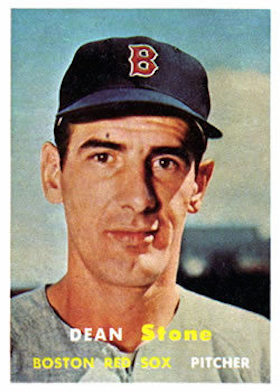

He began the 1957 season with the Senators again, but after three relief appearances (and an ERA of 8.12), he was traded on April 29 to the Boston Red Sox with pitcher Bob Chakales, for Milt Bolling, Russ Kemmerer, and Faye Throneberry. Chakales was the key to the deal for the Red Sox, whose pitching coach, Boo Ferriss, was high on him. “We were fortunate to add a pitcher of Chakales’ experience,” Ferriss told Ed Rumill of the Christian Science Monitor.16 The team had four starters but was looking to supplement them with a spot starter.

Stone lost his first two starts for the Red Sox, though the team only scored two runs in the first loss and none at all in the second. From mid-June on, he worked out of the bullpen save for one spot start against the Yankees, a game he lost, again without run support, 4-1. He was 1-3 with a 5.08 in 17 games (eight starts). He resumed work as a railroad switchman during the offseason.17

Stone was expected to return to the Red Sox in 1958 and trained with them in the springtime, but near the end of the first week of April, he was asked to return to the minor leagues. Optioned to the Triple-A Minneapolis Millers, he had a very good 13-10 (3.18) season. The Millers won the American Association pennant and played in the Little World Series against the International League champion Montreal Royals. In Game Two, on September 27, Stone pitched and won, 7-2, helping his own cause with a home run and a double accounting for two RBIs. The Millers swept in four games.

On March 15, 1959, the Red Sox traded Stone to the St. Louis Cardinals for pitcher Nelson Chittum; both had cleared waivers. Chittum reported to the Minneapolis club; Stone joined the Cardinals at St. Petersburg. “It was not a sensational move,” acknowledged GM Bing Devine of the Cardinals, “but any time we get a chance to look at a pitcher who might augment our left-handed staff, you’ve got to consider it.”18 He started the season in Triple A, this time with the Omaha Cardinals, where he was 9-6 in 24 games, with 18 starts and an ERA of 3.75. Selected to the American Association’s All-Star team, he did not play because he was recalled to St. Louis and got into his first game on July 11. He worked in 18 games, exclusively in relief – except for one start, which he lost 6-0, against the Milwaukee Braves on July 31. In the majors, it was his only decision of the year. His ERA was 4.20, slightly better than the team’s 4.34. In what appears to be the first of several ventures in winter ball, Stone joined the Valencia Industrialists in the Venezuelan Association.

Stone spent 1960 and 1961 in the International League, first with the Rochester Red Wings, where he was 9-7, 3.67, in 56 appearances (11 of them as a starter). In 1961, Rochester became a Baltimore Orioles affiliate and the Cardinals’ affiliate was the San Juan, Puerto Rico/Charleston, West Virginia Marlins. (On May19, San Juan moved to Charleston.) Stone was 12-8 with a 2.73 ERA in 40 games, just over half of them (21) starts. Stone’s improvement did little to earn a promotion but it did garner some trade interest. In December 1960 his name surfaced in a rumored trade to the expansion Senators, a large package that included future HOF righty Bob Gibson. Washington turned down the deal. A year later Stone appeared destined for the New York Mets in the NL expansion draft but he was not selected.

When it came time for the Rule 5 draft in November, Stone was selected by the Houston Colt .45s on November 27. At 31, he found his way back to the major leagues. He got off to a brilliant start, baffling the Chicago Cubs with back-to-back shutouts, a 2-0 win in Houston on April 12 and then, a week later, a 6-0 win at Wrigley Field. The Chicago Tribune observed, “The Cubs are vulnerable to southpaw hurling.”19

He only lasted four innings in his third start, a game that ended as a 5-5 tie after 17 innings.

His fourth time out, he only lasted a third of an inning, tagged for five runs and, ultimately, the loss in the game. Through June 23, he was 3-2 with a 4.27 ERA. On the 25th, he was traded to the Chicago White Sox for Russ Kemmerer (technically, they both cleared waivers in their respective leagues and were sold at the waiver price to the other team), the second time the two of them had been involved in a trade. This time, it was just the two of them. For the White Sox, Stone had only one decision, a win earned on July 15 by facing one batter – Norm Cash – and getting him to fly out to right field. While Stone was still the pitcher of record, the White Sox scored twice in the bottom of the eighth and went on to win, with Dom Zanni in relief. Stone was lifted for a pinch-hitter after the two runs had scored in the bottom of the eighth. His ERA with the White Sox in 30 1/3 innings in 27 appearances was a very good 3.26.

On January 14, 1963, his contract was purchased by the Baltimore Orioles, apparently part of a complicated transaction which sent Luis Aparicio and Al Smith to Baltimore in exchange for the contracts of Hoyt Wilhelm, Ron Hansen, Dave Nicholson, and Pete Ward. In 17 appearances in 1963, all in relief, he was 1-2 (5.12). Though he hadn’t given up a base hit in either of his last two appearances, the last one – his final big-league action — was on June 21.

He was optioned out on June 29. Though he announced his retirement (he had an interest in a propane gas company and was planning to go into construction), he soon changed his mind and worked in 19 games for the Rochester Red Wings, again all in relief. He was 1-1, 4.36.

In 1964, Stone’s last year in professional baseball, he pitched in Kawasaki for the Taiyo Whales. There he threw only 12 innings in six games without a win or loss. He became a free agent on July 10.

Looking back on his career in 1979, he said his biggest thrill in the game hadn’t really been becoming the winning pitcher in the 1954 All-Star Game, but instead was “walking into Yankee Stadium the first time I played there. I can’t remember any of the details of my first game there, but just playing in Yankee Stadium was my biggest baseball thrill.”20

By 1979 he and Peggy had two children – Mary Ann and Dean – and three grandchildren. (Another son died in infancy.) He had his own landscaping business in Silvis, Illinois, just east of East Moline. His son worked with him in the business. He also worked in construction. “I built five homes in Silvis and did all the carpentry on them.” He added, “My big thing is honey bees. For the last three years I’ve been making and selling honey. I’ve got 14 colonies of bees and there are 35,000 to 65,000 bees in a colony.”21

He enjoyed collecting antiques and playing golf and was occasionally accompanied in the latter pursuit by his former Venezuelan winter ball teammate R C Stevens. Stone was a frequent participant in Old Timers Games around the Midwest. In 2005 he was inducted into the Quad Cities Athletic Hall of Fame. Stone became very involved with youth baseball in Silvis, and in 2014 the town’s Little League field was named after him.

“Do they really still talk about it?” Stone asked with a measure of incredulity in 1979 when The Sporting News associate editor Joe Marcin tracked the former hurler to his home to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the only no-pitch All-Star win.22

He died at the age of 88 on August 21, 2018.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Stone’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Joe Marcin, “When Dean Stone Made All-Star Trivia History,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1979: 7.

2 Ed Rommel had been the plate umpire at the start of the game, but in the fifth inning, the umpires changed positions and Stewart assumed duties at home plate.

3 Dean Stone, “How I Started,” Boston Traveler, June 6, 1957: 49.

4 Ibid.

5 Herb Heft, “‘Hungry’ Stone Makes Surprise Pitch for Rookie Prize,” Washington Post, June 13, 1954: C5.

6 Paul Carlson, “Dean Stone Worked Himself to Majors,” Boston Globe, May 5, 1957: A17.

7 Ibid.

8 United Press, “Senators Send 2 Rookies to Minors,” Daily Illinois State Journal, March 25, 1952: 15.

9 “Nats to Take New Look at ‘New’ Sima,” The Sporting News, January 14, 1953: 8.

10 Shirley Povich, “Nats See New Vernon Story for Gil in ’54,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1953: 13.

11 Burton Hawkins, “Dean Stone’s Hurling in Pinches Convinces Harris He’s Matured,” Washington Evening Star, March 20, 1954: 8.

12 “Quotes,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1954: 16.

13 The NL countered with sluggers Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks.

14 United Press, “Washington’s Stone Confirmed Holdout,” Greensboro Record, February 23, 1956: 35.

15 Bob Addie, “Stone Accepts Pay Cut, Three Nats Still Unsigned,” Washington Post, February 24, 1956: 57.

16# Ed Rumill, Christian Science Monitor, May 7, 1957.

17 Bill Cunningham, “Sox Guide Rich with Interesting Data,” Boston Herald, February 21, 1958: 39.

18 “Cards Get Stone for Chittum,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, March 15, 1959.

19 Richard Dozer, “Stone Hurls 2d Shutout in Succession,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1962.

20 Joe Marcin.

21 Dennis Lustig, “Whatever Happened to Dean Stone?,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 12, 1971: 32.

22 Joe Marcin.

Full Name

Darragh Dean Stone

Born

September 1, 1930 at Moline, IL (USA)

Died

August 21, 2018 at East Moline, IL (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.