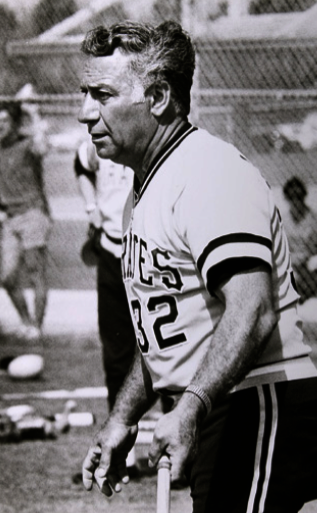

Joe Lonnett

A once-promising Philadelphia Phillies prospect, catcher Joe Lonnett collected fewer than 400 major-league plate appearances yet put in nearly 50 years in professional baseball. An avid fan of the Pie Traynor/Frankie Frisch-led Pirates who played less than 50 miles from his boyhood home, he manned the third-base coaching box during the franchise’s famous “We Are Family” 1979 championship season. A devoted family man, Lonnett was nicknamed “Fred Flintstone” for his uncanny resemblance to the cartoon character. Much beloved by teammates and fans alike, he was widely mourned at his 2011 passing.

A once-promising Philadelphia Phillies prospect, catcher Joe Lonnett collected fewer than 400 major-league plate appearances yet put in nearly 50 years in professional baseball. An avid fan of the Pie Traynor/Frankie Frisch-led Pirates who played less than 50 miles from his boyhood home, he manned the third-base coaching box during the franchise’s famous “We Are Family” 1979 championship season. A devoted family man, Lonnett was nicknamed “Fred Flintstone” for his uncanny resemblance to the cartoon character. Much beloved by teammates and fans alike, he was widely mourned at his 2011 passing.

Born February 7, 1927, in the Rust Belt community of Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania (in the western part of the state less than 20 miles east of the Ohio border), Joseph Paul Lonnett (pronounced \lon-ETT\) was one of seven children born to Frank Rocco Lonnett and his wife, Rose (Barberio) Lonnett. Around 1910 the Lonnetts (a family of three at the time including Joseph’s oldest sister) immigrated to the United States from Italy. Frank found employment in the steel mills while Rose was a stay-at-home mother. Joe, their youngest son, became an accomplished athlete and sports enthusiast. His Beaver Falls High School yearbook cited his prowess on the basketball court above that of his baseball exploits. Graduating in 1944, Lonnett joined the US Navy and served on the battleship Arkansas.

After the war Lonnett was signed by the Cincinnati Reds, but was released in 1947 after batting .221 as an outfielder for Lockport in the Class D PONY League. In 1948 Lonnett was signed by either Phillies scout Eddie Collins Jr. or George Savino, a scout and minor-league manager. Sent to Bradford in the same Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League, Lonnett faced release again, and his manager, Savino, suggested a switch behind the plate. The move worked as Lonnett rebounded to place among the league leaders in nearly every offensive category, and Lonnett embarked on a 22-year affiliation with the Phillies in a wide variety of roles — as a player, scout, coach, and minor-league manager.

Lonnett caught the attention of Phillies farm director Joe Reardon and his corps of coaches, the consensus opinion being: “[Lonnett] has a fine arm, is fast, handles himself like a veteran … [and] can hit. … He looks like a ‘comer.’”1 Lonnett was poised to step into the Phillies’ catching mix the following spring, but on October 30, 1950, he was drafted by the US Army during the Korean War. Assigned to transportation duties in Newport News, Virginia, Lonnett maintained his catching prowess playing alongside Willie Mays on the Fort Eustis (Virginia) baseball squad while occasionally making the 600-mile round trip to Philadelphia to participate in Phillies workouts. Discharged on October 29, 1952, Lonnett joined the catching competition at spring training in Clearwater, Florida, in 1953. Despite a strong spring, he was optioned to the club’s Triple-A affiliate in Baltimore on March 22. “He was as good a receiver or better than either [of our existing catchers] Stan Lopata or Smoky Burgess,” explained manager Steve O’Neill. “But he needs a full year’s work to put on the finishing touches.”2 But a full year’s work was not in the offing. The bulk of catching responsibilities for the International League’s Baltimore Orioles went instead to veteran receivers Martin Tabacheck and Al “Moose” Lakeman and, with little use, Lonnett’s numbers suffered accordingly.

The season had actually started promisingly for the 26-year-old. Injury and prolonged illness had sidelined the older catchers at the start of the campaign and Lonnett capitalized on the opportunity. A grand slam in his first starting assignment, on April 24, sparked a 6-2 win over the Buffalo Bisons. Six of his first 11 hits were home runs, including a second bases-loaded jolt. But Lonnett suffered a jammed finger on May 23 and a subsequent knee injury, and the healthy return of Tabacheck and Lakeman resulted in less than 200 plate appearances for the season. Despite limited play, he and righty hurler Jack Sanford (an eventual National League Rookie of the Year) were projected to make the jump to the Phillies the following spring, with director of player personnel John Nee reportedly “a big booster for the dark-haired backstop.”3

After a successful winter league campaign in Colombia, Lonnett batted near .300 in the Grapefruit League. Determined not to lose playing time, he had a fractured finger taped and continued playing. Trade rumors had Lopata or Burgess being sent to Milwaukee for a reserve infielder, but nothing came of this. Despite his inclusion in the list of prized rookies published in April by The Sporting News,4 manager O’Neill reassigned Lonnett to Triple-A Syracuse after having persuaded him to accept a lower-than-sought salary. Excluding a brief promotion in May after Lopata was injured and a September call-up (in neither instance did he get into a game), Lonnett spent the entire 1954 season with Syracuse.

And what a season that would be! The Chiefs became the first team to win the International League playoff championship after a fourth-place finish in the regular season. This success was realized largely on the shoulders of Lonnett. Playing in only 98 games because of the call-ups and time lost to injury, Lonnett still placed among the league leaders in home runs and finished the campaign with a batting line of .268-21-63. A poll of the 16 major-league farm directors rated him one of the league’s top prospects. But an advance to the majors was put on hold the following spring when his knee was found to have torn cartilage. Lonnett lost two months when he went under the knife in April 1955, then reinjured the knee on July 13. He ended his second season in Syracuse with just 60 at-bats in 26 games.

Lonnett’s long-awaited promotion to the Phillies came in 1956 but not before another injury in spring training, a broken nose from a pitched ball (the injury-prone backstop sustained yet another injury that summer). Under the direction of manager Mayo Smith, who took over the reins the preceding year, the Phillies planned to use Lonnett as a reserve catcher behind 13-year veteran Andy Seminick and move Lopata to first base. This plan worked only until the 35-year-old Seminick demonstrated that his best hitting years were behind him (.146 after May 30). Smith returned Lopata to the starting position behind the plate and designated Seminick as his backup. Relegated to occasional pinch-hit duties, Lonnett made only seven plate appearances after June 5.

No further consideration was given to moving Lopata to first base in 1957 with the advent of powerful left-handed-hitting rookie Ed Bouchee. Meanwhile, Seminick retired, leaving the backup catching responsibilities solely to Lonnett, who had a career-high 160 at-bats. Though he hit only .169, Lonnett’s safeties seemed to come in a most timely manner. On June 16 his double in the sixth inning of a scoreless duel between Curt Simmons and Milwaukee’s Lew Burdette robbed the Braves righty of a no-hit bid, then Lonnett scored from third base after a sacrifice fly to provide the margin of victory in a 1-0 contest. When Lopata was sidelined by muscle strain beginning in late June, Lonnett flourished in the starting role. On July 4 his first major-league home run (the first of four within a 10-day span) helped the Phillies sweep a doubleheader from the New York Giants. Described as one who would “never win any sprint races,”5 he managed an inside-the-park four-bagger at Wrigley Field against the Chicago Cubs on July 29 that contributed to a 6-0 win. But Lonnett’s real contributions came with the glove. For the second of three consecutive seasons, Lopata placed among the league leaders in errors for a catcher. Meanwhile, Lonnett played error-free until, with only 11 games left in the season he was called for interference. His.997 fielding percentage led NL catchers with 200 or more putouts.

An encouraging start to the 1958 season — .333 in 15 at-bats while still serving as Lopata’s backup — succumbed to 29 hitless plate appearances. On June 13, after he started a game in San Francisco, the Phillies traded Lonnett to the Braves for catcher Carl Sawatski. Assigned to Milwaukee’s Triple-A affiliate in Wichita, Lonnett didn’t resurface in the majors for more than a year.

Fred Haney, manager of the National League champion Milwaukee Braves, sought to enter the 1959 season with three catchers. Among those Lonnett found competing against him that spring was Stan Lopata, traded to the Braves on the last day of March. Failing in his attempt to stick with the Braves, Lonnett was assigned to Triple-A Louisville, where he hit .291 in 86 at-bats. However, on May 28 Lonnett was sent to the Detroit Tigers organization in a multiplayer swap involving minor leaguers. Lonnett refused to report to the Triple-A Charleston (West Virginia) Senators. Perceiving the trade as a means by which the Braves could forgo an agreed-upon restoration of a $3,200 pay cut if he produced well in Louisville, Lonnett instead went home to Beaver Falls and the trade was nullified. The Braves organization sought to have Lonnett placed on the disqualified list, but the Phillies organization stepped back into the picture.

The Phillies’ Buffalo affiliate was threatened by a series of injuries. On June 18 the Phillies purchased Lonnett’s contract and agreed to pay him about half the money he felt he was due from the Braves. Lonnett picked up at Buffalo where he’d left off in Louisville, then on June 10 was called up to Philadelphia after catcher Valmy Thomas was injured in a home-plate collision. Two days later he swatted a three-run home run during a loss to the Cubs. He got most of the starting assignments over the next 29 games, during which the last-place club was 16-13. Lonnett drew credit for his handling of the pitching staff but when he again lost his hitting stroke — .089 in his final 56 at-bats — he was again relegated to backup duties. On September 26 he had what turned out to be his final three major-league at-bats, against the Braves’ Warren Spahn, and was assigned to Triple-A Buffalo at the end of the season.

Never one to escape injury (both on the field and in a car accident in 1959), Lonnett continued in the minors for portions of four seasons, including an all-star campaign in the International League in 1960. His last season was in 1963 with the Arkansas Travelers, where he was teamed briefly with a young slugger whose high-school basketball games he once officiated, Richie “Dick” Allen. “I felt closer to [Lonnett] than anyone,” Allen said.6 Lonnett returned to Beaver Falls, where he scouted for the Phillies in and around western Pennsylvania. In June 1965 he took over the reins of the Huron (South Dakota) Phillies in the short-season Northern League. The next year Lonnett became the first professional manager of another budding slugger, Larry Hisle.

The careers and lives of Lonnett and Chuck Tanner are remarkably similar in many ways. Born 17 months and 23 miles apart, they both spent about the same number of years lingering in the minor leagues. Though Tanner spent twice as many years in the majors, neither player ever attained the level of full-time regular. A lifelong kinship was forged when they were teammates on a barnstorming squad roaming Pennsylvania after the 1957 season. In 1970 Tanner, after taking the reins of the Chicago White Sox, Tanner hired Lonnett as his third-base/catching coach.

From 1971 to 1984, Lonnett and fellow coach Al Monchak accompanied Tanner from Chicago to Oakland to Pittsburgh. The trio won the praise of White Sox general manager Roland Hemond, who told The Sporting News, “Tanner has done the best job of managing I’ve ever seen. With coaches … Joe Lonnett [and] Al Monchak … to help, [they’ve] molded the talent we’ve been able to acquire into a high-spirited, enthusiastic and aggressive ballclub.”7 Lonnett was largely credited with shepherding the catching careers of Brian Downing, Ed Ott, and Steve Nicosia, while his humor was oft cited for breaking the monotony of a long season. Assessing the poor playing conditions in Comiskey Park after the White Sox had replaced the AstroTurf infield with natural grass in 1976, Lonnett suggested, “They must have used bumpy blades.”8

In the spring of 1978 White Sox pitcher Wilbur Wood “turned an extra exhibition game with the Pirates into an eventual farce when he glued down the personal effects of Pittsburgh coach Joe Lonnett. [Joe] had the last laugh when he pinch-hit and, after ducking a Wood lob at his head, singled. He … scored on a single … laugh[ing] all the way home.”9

Described as a “fellow who takes charge,”10 Lonnett called on his Roman Catholic upbringing to help maintain a strong sense of right and wrong. As the salary dispute with the Milwaukee Braves indicated, he was no wallflower when it came to expressing his views. In the winter of 1953, while playing in Colombia, he was one of four players protesting for better living arrangements for himself and his teammates. Years later his actions spoke volumes when he left a restaurant that would not serve African-American star Dick Allen. Allen once referred to another as “a good baseball coach, like Joe Lonnett.”11 On this occasion, Lonnett was teaching something more than just baseball.

Lonnett’s tenure with the Pirates ended after the 1984 season. He declined an offer to manage the Prince William (Virginia) Pirates in the Class A Carolina League. He instead spent his later years as a roving minor-league instructor for the Pittsburgh and Toronto organizations. In the 1990s, as he approached his 70th birthday, Lonnett could be found participating in the fan-favorite Legends of Baseball spring exhibitions.

Lonnett was inducted into the Beaver County (Pennsylvania) Sports Hall of Fame in 1980. In 2004 he attended the 25th anniversary celebration of the 1979 championship team at PNC Park. On those few occasions when Lonnett was not attending to baseball-related functions, he enjoyed shooting pool and bowling, sporting a 200 average in the latter while possessing the ability to run the table in the former. “He was good at anything he did both athletically and otherwise,” his daughter Barbara remembered. In later years Lonnett battled Alzheimer’s disease and was cared for by Alvida, his wife of 56 years. He died on December 5, 2011, two months shy of his 85th birthday. He was survived by Alvida, five daughters, and six grandchildren.

Former pitcher Kent Tekulve said of Lonnett, “He was that universal personality in the clubhouse who would make you happy just looking at him. You would be happy about being a Pittsburgh Pirate. You would be happy about being part of this team and you would be happy about getting to work with Joe Lonnett.” Former pitcher and later Pirates broadcaster Jim Rooker said, “There are people with big hearts, but Joe he had a mega-heart. … He was such a wonderful person.”

A player who never cracked .200 in his major-league career, Lonnett often quipped that if a kid found his baseball card lying in a ditch he’d keep walking. Lonnett will never be Cooperstown-bound. But should a Hall of Fame be established for beloved and generous human beings Lonnett would undoubtedly be a first-class inductee.

This biography appears in “When Pops Led the Family: The 1979 Pitttsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bill Nowlin and Gregory H. Wolf.

Last revised: September 29, 2023 (zp)

Sources

The author wishes to thank Lisa Smith-Curtean, a volunteer at the West Waco (Texas) Library and Genealogy Center, for her helpful support researching the 1940 census. Further thanks to Barbara Lonnett and the extended Lonnett family for their valuable input, and Rod Nelson, chair of the SABR Scouts Committee.

triblive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/sports/pirates/s_770986.html#axzz2dvD72XRg

youtube.com/watch?v=58C7-7gRSKI

Lonnett, Barbara, email correspondence (from which all unattributed quotes derive), September 2013 to April 2014, and June 22, 2015.

Notes

1 “Lonnett, Phil Kid Catcher, Called Comer,” The Sporting News, January 21, 1953: 21.

2 “Kazanski, 80-Grand Kid, Given Shot at Shortstop Job on Phils,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1953: 20.

3 “Phillies Flash Wide Grin Over Record Harvest,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1953: 14.

4 “Power, Lynch Tabbed Prize Rookies,” The Sporting News, April 14, 1954: 2.

5 “Vintage Trio Joins Rookies as Phillies’ Surprise Packages,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1957: 4.

6 “Allen, Fast-Stepping Traveler, Beating Path to Phillies’ Door,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1963: 31.

7 “‘Alger’ Hemond Major Exec of Year,” The Sporting News, December 2, 1972: 35.

8 Dick Young, “Young Ideas, The Sporting News, June 19, 1976: 18.

9 “White Sox Left With Raw Receivers,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1978: 20.

10 “’54 Phillies to Be Restyled Into Junior Whiz Kid Model,” The Sporting News, November 11, 1953: 8.

11 Dick Young, “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1974: 14.

Full Name

Joseph Paul Lonnett

Born

February 7, 1927 at Beaver Falls, PA (USA)

Died

December 5, 2011 at Beaver, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.