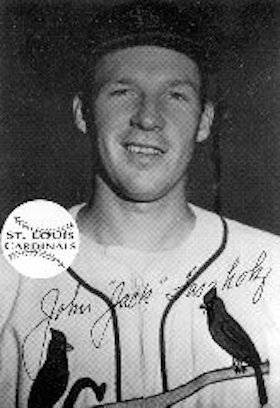

Jack Faszholz

A sleek passenger train pulled out of the Tampa, Florida, Union Station in late March of 1953. Stan Musial, Red Schoendienst, and other St. Louis Cardinals on board looked forward to the start of another baseball season. Longtime farmhand Jack Faszholz hoped to finally fulfill his major-league dream.

Faszholz, a 6-foot-3-inch, 205-pound right-hander, was nearly 26 years old and beginning his ninth season in professional baseball. He recalled pitching “just OK” at spring training that year for the Redbirds. “I think they figured I was worth a look-see, though,” he said. “I was passable.”1

The native St. Louisan ultimately appeared in four games and threw 11 2/3 innings in the majors, all with the Cardinals. He started once and relieved three times, ending up with a won-loss record of 0-0 and a 6.94 ERA. His entire professional baseball career, though, lasted 12 seasons. He won 128 games, including a record-setting 80 wins for the Rochester, New York, Red Wings of the International League.

Some sportswriters and fans liked to call Faszholz “Preacher.” They knew that in the offseason, he attended classes at Concordia Seminary in St. Louis and hoped to become a Lutheran minister after his playing days were over. Faszholz said that his faith helped him as he toiled all those years in the minors. “I sort of had a philosophy to work as hard as you can and realize any success you might have is by the grace of God,” he said.

John Edward “Jack” Faszholz was born April 11, 1927, the second child of Richard and Mamie Faszholz. Richard, an avid St. Louis Browns fan, worked as a bookkeeper for the E.I. Dupont Co. Dupont promoted him to a sales position in 1934, and the family moved to Seattle. There, Jack began playing softball and baseball. He even won his first award, competing in the popular, citywide Old Woody contest in 1937. The object? Stand 50 feet from a plywood frame (a.k.a, the Old Woody) and hurl a baseball through a small rectangular hole in the frame. Try to throw three strikes before throwing four balls. Jack recorded four K’s, finishing tops among 10-year-olds. He earned two tickets to a Seattle Indians PCL (Pacific Coast League) game.

In 1938, the Faszholz family packed up and moved again, this time to Berkeley, California, in the San Francisco Bay Area. Jack, along with his four brothers and one sister, played sports the year round at Live Oak Park in north Berkeley. Jack also worked on his game while at Garfield Junior High. Later, he starred in basketball and baseball at Concordia College High School in Oakland. (Faszholz spent just a couple of weeks at local Berkeley High. One of his classmates was future major-league player, manager, and brawler Billy Martin. Not surprisingly, Faszholz recalled him, in a word, as “rowdy.”)

On the Concordia baseball diamond, Jack started out as a shortstop. His older brother, Dick, talked him into trying his luck on the mound. Jack reluctantly agreed. ‘It was such a small school, and there wasn’t anyone else,” he said. “I really just wanted to play shortstop.”

During Jack’s junior season at Concordia, Esquire magazine sponsored a national high-school All-Star game, to be played at the Polo Grounds in New York City. A team comprised of players hailing from east of the Mississippi River would compete against a team made up of players from west of the Mississippi.

Several qualifying games led up to the big showdown. Faszholz competed in a contest at Seals Stadium in San Francisco. Major-league scouts filled the stands. Tommy Fitzgerald, a bird-dog scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers, offered Faszholz a contract and a $500 signing bonus. Charlie Wallgren from the Boston Red Sox countered with a $650 bonus offer. Jack signed the Boston deal after talking over both contracts with his dad. “I guess we goofed, though,” Faszholz said. “We should have gone back to the Dodgers and told them about the Red Sox’ offer.”

Faszholz didn’t advance out of Seals Stadium in the Esquire competition. Even so, in the summer before his senior year at Concordia, 1944, he traveled cross country and reported to the Roanoke, Virginia, Red Sox of the Class-B Piedmont League. The 17-year-old ran into a little culture shock along the way. One morning, Faszholz changed trains at a station in Bluefield, West Virginia. Looking around, he saw the “colored only” drinking fountains. “Coming from California, that was a little different,” he said.

Faszholz compiled a 2-6 won-loss record as a starter and reliever for Roanoke, which finished in last place. Second baseman Eddie Popowski served as the team’s player-manager. Roanoke, like most minor-league clubs back then, didn’t have a pitching coach. “About the only thing (Eddie) said to the pitchers was “Do your running,’” Faszholz said.

The teenager with a crop of blond hair did strike out the great Jimmie Foxx in one game. The Chicago Cubs had sent down “Double X” to manage their Piedmont team in Portsmouth, Virginia. (Foxx played just 15 games for the Cubs in 1944 and retired following the 1945 campaign, as a Philadelphia Phillie, with 534 career home runs.) Faszholz fanned Foxx on a series of well-placed fastballs after the slugger had inserted himself into the lineup as a pinch-hitter. Following the game, Faszholz said he overheard Foxx talking to reporters. The future Hall of Famer offered an alibi for getting whiffed by such a young hurler. “He said, ‘I don’t see how anyone hits under these lights,’” Faszholz said. “And, to be truthful, they were pretty bad. About as bad as the team that year.”

Faszholz sat out the 1945 season and completed his schoolwork at Concordia on an accelerated program in pre-ministerial studies. He reported back to Roanoke in 1946. This time, with several players returning from action in World War II, the team won the Piedmont League pennant. Roanoke lost in the playoffs to the Newport News, Virginia, Dodgers, a Brooklyn farm club that included future All-Star Gil Hodges and future Rifleman TV star Chuck Connors. Faszholz finished 8-5 and posted a sparkling 1.96 ERA over his 110 innings.

The Red Sox promoted their prospect the following season to Scranton, Pennsylvania, a Class-A team in the Eastern League. There, Faszholz struggled a bit, going 9-10; his ERA ballooned to 4.67. Boston ordered him back to Roanoke for the 1948 campaign, and he improved to 9-5 with a 3.29 ERA. In what would become a familiar pitching performance, Faszholz scattered nine hits in one game against Portsmouth and still tossed a 6-0 shutout, according to the Roanoke World-News. Later in the season, he surrendered 10 hits and beat the Richmond, Virginia, Colts, a New York Giants affiliate, by a 3-2 margin. “I’d do that a lot,” Faszholz said. “I’d give up the hits, but I didn’t walk many guys.”

By the end of the 1948 season, Faszholz had run of options with Boston. St. Louis drafted the 21-year-old and assigned him to Columbus, Georgia, in the South Atlantic League. Vern Mackie, manager of the Lynchburg, Tennessee, Cardinals, had recommended Faszholz to the St. Louis brass. The pitcher threw an impressive 13-inning game in a losing effort against Mackie’s squad.

Gene Faszholz, one of Jack’s younger brothers, played first base and outfield for Columbus. Gene got into every inning of every game in 1949. Jack, meanwhile, compiled a 20-14 won-loss mark and 3.01 ERA in what he called “my most enjoyable season in professional baseball.” Following that campaign, popular St. Louis Globe-Democrat columnist Bob Burnes featured a promising quote from Joe Mathes, the head of the Cardinals’ farm system. Mathes said this about Faszholz: “We consider him a good prospect … He takes charge of the ball game and works on every hitter. He has good control, and his curve is good. … He’s the kind of fellow you want to keep an eye on.”2 Besides featuring a fastball and curveball, Faszholz said he also threw a change-up. Later in his career, he added a forkball. “My fastball had a tendency to sail, like a slider,” Faszholz said. “I couldn’t consciously throw it that way. I just threw it, and it moved that way.”

St. Louis assigned Faszholz to the Red Wings in 1950. Thus began his long career with the Cardinals’ top farm team. He finished 5-3 with a 4.03 ERA that first season, starting in some games and relieving in others, and improved to 12-9 with a 3.41 ERA in 1951.

About then, word got around that Faszholz was taking Seminary classes during the offseason. One of the Rochester sportswriters began referring to him as “The Preacher” in print, and fellow players picked up on the nickname. “But, no one was asking me questions about Bible verses,” he said.

This was a busy time for Faszholz. On Oct. 25, 1951, he got married to Annette Gaebler. Jack had met his future bride while on a blind date at a St. Louis Flyers minor-league hockey game in 1949. Annette was studying nursing at the local Lutheran Hospital. The newly wedded Mr. and Mrs. Faszholz enjoyed a short honeymoon in Hannibal, Missouri, located about 110 miles north of St. Louis and famous as the boyhood home of writer Mark Twain.

Faszholz reported to Rochester in the spring of 1952 and enjoyed another big year. He posted a 15-8 won-loss mark and a 3.67 ERA. The Cardinals invited him to spring training that following February. Faszholz started the Cardinals’ spring-training opener at Al Lang Field in St. Petersburg, and shut out the New York Yankees over three innings. He even struck out a young Mickey Mantle in that one. Faszholz tossed a few more games in Florida, some good ones, some merely so-so. The Cardinals liked what they saw.

St. Louis, coming off a third-place campaign and an 88-66 record, opened the 1953 season on April 14 in Milwaukee. Faszholz sat in the dugout for the first several games and waited for his chance. Second-year manager Eddie Stanky finally called him into action on April 25, at Wrigley Field in Chicago. Rain had delayed the game by 30 minutes. Cardinals beat reporter Bob Broeg, writing in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, described it as a “gloomy afternoon.”3 Redbird starting pitcher Stu Miller probably would have agreed.

Chicago knocked around Miller for eight hits and six runs (all earned) in 3 1/3 innings. The Cubs built a 9-3 lead before Stanky brought in Faszholz to pitch in the bottom of the fifth. The rookie gave up a double to Toby Atwell, the first batter he faced, and then put away Paul Minner and Eddie Miksis. Frank Baumholtz followed with an RBI double. Dee Fondy flew out to end the inning. Faszholz said that Stanky asked him afterward, “When was the last time you cussed?” Faszholz gave him an honest answer: “When Baumholtz got that bleeding hit off me.”

The Cubs ended up winning 10-6. Miksis, Fondy, Preston Ward, and Bill Serena all drove in two runs to lead the Chicago attack. Red Schoendienst went 4-for-5 for the Cardinals. Broeg noted in his story that Faszholz was “making his first appearance as a Cardinal.”4

Faszholz did not get into another game for about three weeks. He made his only start in the big leagues on May 18 against the New York Giants at Busch Stadium in St. Louis. Sixty-three years later, Faszholz offered a play-by-play description of that spring afternoon. “Well, I remember (the game) almost pitch by pitch,” he said. Davey Williams led off with a walk. Alvin Dark knocked a bloop single down the third-base line.

Preacher Faszholz gave up two runs in the first inning before settling down. He retired the side in order in the second and allowed just lone singles in the third and fourth frames. Hank Thompson, though, ripped a two-run home run in Faszholz’ fifth and final inning. The Preacher still led 5-4 at that point, thanks to two RBIs from Schoendienst and one apiece from Steve Bilko, Enos Slaughter, and Ray Jablonski.

The Giants clawed back, scoring four runs against the St. Louis bullpen in the seventh and won, 8-6. Monte Irvin smashed the big hit, a three-run homer off Cardinals reliever Al Brazle. Faszholz walked one, struck out four and allowed six hits during his stint. Broeg wrote that “the handsome giant from Concordia Seminary did all right.” Stanky said in the article, “And, he’ll start again—soon.”5

That never happened. Faszholz’ next game came five days later, but in relief, at home against the Cincinnati Reds. He appeared in the ninth inning with the Cardinals already down, 5-0. Starter Cliff Chambers had given up three runs; reliever Eddie Erautt had allowed two. Faszholz surrendered two hits, one of them being Gus Bell’s second home run of the day. Cincinnati ended up winning, 6-0.

One week later, on May 30, Faszholz pitched his final game in the majors, once again at Busch Stadium, in the second game of a doubleheader against Milwaukee. The Braves took the opener, 5-2, thanks to a complete-game effort by Warren Spahn and three RBIs from left fielder Sid Gordon. Erautt started for St. Louis against Don Liddle in the second game. Neither pitcher made it out of the third inning.

Milwaukee tagged Erautt for five hits and three runs in 2 1/3 innings. Stanky signaled for Faszholz to provide some relief. The Braves, though, kept hitting. Faszholz pitched 3 2/3 innings and allowed six hits and three runs, all earned. Future Hall of Famer Eddie Mathews blasted a two-run homer. Faszholz said, “I think that one is still flying around on South Grand Avenue (outside the ballpark).” Broeg called Faszholz “Preacher” in his article, but acknowledged that “Preacher Jack Faszholz was pounded, too.”6 The Braves ended up winning 6-4.

Soon after that game, St. Louis sent a disappointed Faszholz back to Rochester. The Preacher went a tidy 10-6 for the Red Wings in 1953 despite missing nearly two months of action. The following year, Faszholz enjoyed his best International League campaign. He compiled an 18-9 record, pitched a career-high 225 innings and finished with a 3.20 ERA. As was the case in most seasons, he didn’t strike out many batters (62), but he didn’t walk many, either (50). In a guest column that he wrote July 9, 1954, for the Rochester Times-Union, Faszholz offered this revealing pitching tip: “Control is the key to good pitching in every league. … Don’t worry too much about an assortment of pitches. If you can develop a good fastball and even a fair curve, that’s enough.”7

While with Rochester, Faszholz pitched his home games at Red Wing Stadium, built in 1929. He remembered it as a “fair” ballpark, not really favoring hitters or pitchers. As often as he could, Faszholz worked on the edges of the strike zone and let his fielders do the work. Faszholz said that his success—both at home and on the road–sometimes baffled opposing hitters. He didn’t throw a blazing fastball. “I think some people surmised that I was getting some help from above,” he says. Red Wings manager Harry “The Hat” Walker, maybe with a sense of superstition, liked to pitch Faszholz on the Sabbath. He reasoned, Faszholz said, “You can’t beat the Preacher on Sundays.”

The Montreal Royals, Brooklyn’s top farm team, couldn’t defeat Faszholz on Sunday or almost any other day in 1954. Faszholz said he prevailed against the Royals five or six times that season. He recalled one at-bat that thoroughly frustrated International League slugger Glenn “Rocky” Nelson.

The left-handed hitter walked to the plate late in one game with Montreal trailing. Faszholz got behind in the count and didn’t want to surrender a walk. He grooved a pitch to Nelson, who hit a sharp liner to Red Wings first baseman Tom Alston. The hot shot ricocheted off the top of Alston’s glove, right into the glove of second baseman Lou Ortiz for an out. Moments later, Faszholz heard a ruckus coming from the Montreal dugout. Bats were flying, profanity filled the air. Suddenly, Nelson yelled out toward Faszholz, “You’re sure making a believer out of me!”

Faszholz’ big 1954 campaign earned him an invitation to spring training in ‘55. This time, he pitched eight innings in Florida and posted a sub-2.00 ERA. Once again, he hopped aboard the team train and prepared for opening day, scheduled for April 12 at Wrigley Field. Just hours before the first pitch, Faszholz roamed the outfield, shagging fly balls. A clubhouse boy walked up to him. Mr. Stanky wants to see you, the boy said. Stanky gave Faszholz the disappointing news. He told the veteran prospect to get on board the next train to Rochester. “Stanky said Harry the Hat wanted me back in Rochester to pitch the home opener,” Faszholz recalled, a bit glumly.

In 1955, the Preacher finished 13-11 with a 3.96 ERA in 193 innings. The next year, he fell to 7-13 with a 4.86 ERA over 124 innings and called it quits. He was 29 years old, his oldest child was about to start kindergarten, and he needed to complete just one more class at the Seminary. Plus, he added, “It didn’t look like I was going to get another opportunity.” Faszholz retired as the winningest pitcher in the history of Rochester Red Wings baseball, a title he still holds. During his eight seasons there, he compiled an 80-59 won-loss record (.576 winning percentage) and a 3.75 ERA in 1,145 innings. Faszholz struck out 350 batters as a Red Wing and walked 360.

Overall in the minors, he went 128-100 and retired with a 3.63 ERA over 1,891 1/3 innings. He fanned 707 and walked 638. In the majors, Faszholz gave up 16 hits and nine earned runs in his 11 2/3 innings of work. He struck out seven and walked just one batter.

In a talented athletic family, Faszholz stood out the most. Dick Faszholz, the oldest of the brothers, earned a spot on the USA men’s basketball team. He played in the 1951 Pan-American Games in Argentina. Tom Faszholz also played basketball and nearly made the St. Louis Hawks NBA squad. Gene Faszholz and Dave Faszholz both spent several years toiling in minor-league baseball, but neither got a call-up to the majors. Katherine Faszholz, meanwhile, was a pretty fair tennis player. “I think we all encouraged each other without really knowing it,” Jack said. “My older brother, Dick, encouraged me in sports. I encouraged Gene, and so on.”

The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod ordained Faszholz as a minister in 1958. He served many congregations through the years as an interim pastor, but spent most of his career as a teacher, coach, and athletic director. Faszholz led the baseball program at Lutheran High School South in St. Louis for nearly 20 seasons. He also completed his master’s degree work in physical education at Washington University. Later, Faszholz coached at Concordia University Texas in Austin for 12 years. He retired from that position in 1990, in part due to chronic hip problems.

The Red Wings inducted Faszholz into the team’s Hall of Fame in 1990. Concordia University did the same, in 2015, and honored him with a tribute video. Several of his former players offered kind words. Mike Tate, a former pitcher, said, “I would describe Coach Faszholz as a man of modesty, a man of humility, a man who taught us how to deal with adversity and challenges through the game of baseball.”8

Jack and Annette Faszholz settled in rural Belle, Missouri, following Jack’s coaching days. Rev. Faszholz served as associate pastor for several years at nearby Mt. Calvary Lutheran Church. In 2015, he and Annette moved to St. Louis, where they attended Salem Lutheran Church in the Affton area and where their six children reside. Faszholz’s Rochester Red Wings Hall of Fame plaque hangs in the couple’s tidy living room, along with other baseball memorabilia, including a photograph of Sportsman’s Park (renamed Busch Stadium), torn down in 1966. Faszholz looked back on his big-league career with bittersweet memories.

“I was disappointed it wasn’t a longer career, and I was really disappointed that I wasn’t given more of an opportunity in ’55,” he said. “But, as they say, there’s nothing like the Big Show.”

Jack Faszholz passed away on March 25, 2017, just a few weeks short of his 90th birthday. A memorial service was held in his honor on April 26 at Salem Lutheran Church in Affton, Missouri. Memorial services also were held April 29 at Mt. Calvary Lutheran Church in Belle, Missouri, and May 2 at Concordia University-Texas in Austin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Almanac.com, Baseball-Reference.com, RedWingsBaseball.com, the Roanoke Word-News, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, and the Seattle Times, as well as a Concordia University Texas tribute video to Jack Faszholz: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SkdLKG2LdgE.

Notes

1 Author interview with Jack Faszholz, June 16, 2016. All quotations from Faszholz, unless otherwise attributed, came from this interview or a follow-up interview on June 30, 2016.

2 Robert L. Burnes, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, date unknown.

3 Bob Broeg, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 26, 1953: 1D.

4 Ibid.

5 Bob Broeg, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 19, 1953: 4C.

6 Bob Broeg, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 31, 1953: 1C.

7 Jack Faszholz, Rochester-Times-Union, July 9, 1954: 19.

Full Name

John Edward Faszholz

Born

April 11, 1927 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

March 25, 2017 at Belle, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.