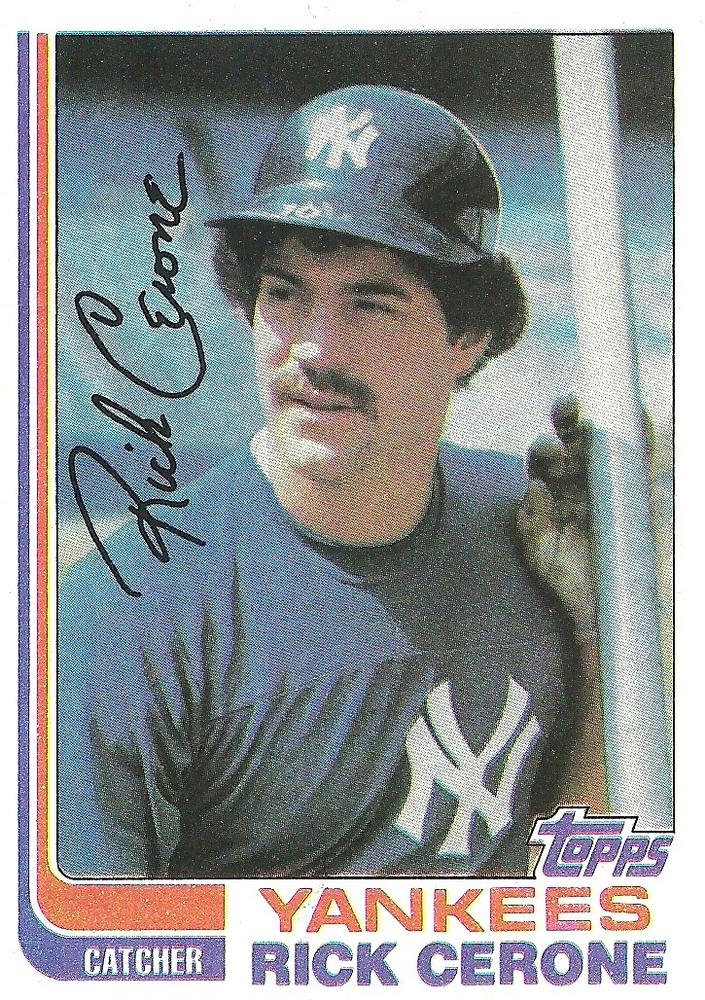

Rick Cerone

Catcher Rick Cerone had an 18-year career in the major leagues (1975-92), but he used his athletic talent and fame well beyond the baseball field. An excellent multiple-sport athlete in his youth, his real love was baseball. Prior to his major-league career, he was a college baseball star, and after his time in the majors, he worked as a broadcaster in both radio and television. Later, he became the owner of his own minor-league club. He loved his hometown of Newark, New Jersey, and used his prominence to help his hometown and to serve needy families. As a professional athlete, he was known for building strong relationships with his teammates and coaches, as his leadership qualities behind the plate allowed him to connect with pitchers and infielders.

Catcher Rick Cerone had an 18-year career in the major leagues (1975-92), but he used his athletic talent and fame well beyond the baseball field. An excellent multiple-sport athlete in his youth, his real love was baseball. Prior to his major-league career, he was a college baseball star, and after his time in the majors, he worked as a broadcaster in both radio and television. Later, he became the owner of his own minor-league club. He loved his hometown of Newark, New Jersey, and used his prominence to help his hometown and to serve needy families. As a professional athlete, he was known for building strong relationships with his teammates and coaches, as his leadership qualities behind the plate allowed him to connect with pitchers and infielders.

Richard Aldo Cerone was born in Newark on May 19, 1954, and grew up there. His father, Aldo Cerone, worked for the US Post Office for 38 years. His mother, Rosemary “Toots” Cerone (née Buccino), who lived to 97, was a waitress at Thomm’s Restaurant in Newark for many years.1 Rick described her as dressing like a queen and prettier than the queen. He had one sibling, an older sister named Patti.

As a youth, Cerone was a very active athlete. “They [his parents] never pushed me into sports,” he noted. However, they were always positive about his activities and attended his games.2

Cerone attended Essex Catholic High School, graduating in 1972. The school, private and all-male at the time, was run by the Congregation of Christian Brothers and sponsored by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark. At its peak, it had as many as 2,500 students, but declining enrollment ultimately forced it to close in 2003.3 Cerone was the starting quarterback for the football team, the star baseball player, and was part of the state champion fencing team. He earned All-State recognition in all three sports.4

Cerone dreamed of playing big-time football, but he wanted to attend a college where he could also play baseball. In spite of this, there was interest from baseball scouts about being drafted, and in the summer of 1972, he attended a tryout at Yankee Stadium. During the tryout, he didn’t perform as well as he expected – it was raining and he was soaking wet.5 He was offered 60 football scholarships, including one from Ohio State, but none for baseball. Said Cerone, “I wanted to play football and baseball in college and nobody in the big schools would let you.”6

Cerone originally signed a letter of intent to play quarterback at the University of Rhode Island.7 However, his heart was near home, and he decided to play for head coach Mike Sheppard at New Jersey’s Seton Hall University. Cerone explained, “So, the last minute, Mike Sheppard said, ‘Listen, I don’t have a scholarship, but we’ll find one if you want to stay home and just play baseball.’ And when you think about it, you have to make a decision that really affects the rest of your life.”8

Cerone helped lead Seton Hall to back-to-back College World Series appearances in 1974 and 1975. He also earned first-team All-America honors in 1975. When he graduated, he owned program records for most career doubles, most home runs in a season and career, all-time slugging percentage, and most RBIs in a season. He still ranks in the top 10 in Pirates history in career batting average and home runs. The catcher was also a two-time academic all-American.9 In 1982, he was inducted into the Seton Hall Athletic Hall of Fame and his number (15) was retired.

Despite his ultimate success at Seton Hall, his college career had gotten off to a disastrous start. Playing right field in the 1973 opener against Florida International, he did something to anger skipper Sheppard. “I must have popped off, and he yanks me out of the game and says, ‘Just go run.’” Cerone recalled. “I said, ‘What do you mean just go run?’ He said, ‘Run foul lines. I don’t want to see you; get away from me.’”10

So Cerone ran, and ran, and ran. “The team was on the bus afterward and I’m still running line to line,” Cerone said. “I must have been running for two-and-a-half hours, and someone finally said, ‘Hey Shep, what about Rick? The lights are going to go out and he’s still running out there.’”11

In 1975, Cerone was named to the College World Series’ All-Tournament team after hitting .462 with five RBIs over three games, which included an 11-0 romp over a 50-win Florida State squad. The Pirates, the only northeastern program in the bracket, narrowly missed defeating eventual champion Texas and advancing to the semifinals.12

“We deserved to be there as one of the best teams in the country, and we proved it,” Cerone said.13

Cerone entered the major-league draft after his junior year and was drafted by the Cleveland Indians with the seventh overall selection. Although the draft that year was considered weak, it included major-leaguers Lee Smith, Carney Lansford, and Dave Stewart. “I was actually in the big leagues in ’75, my junior year. But I did go back and graduate on time with my class of ’76,” said Cerone.14

After being drafted, he quickly signed with the Indians, who sent him to the Oklahoma City 89ers, their Triple-A team in the American Association. There he played in 46 games and hit .250. At Oklahoma City, he showed the Indians his ability to handle pitchers and displayed his strong throwing arm. He was called up to the majors in August and made his debut in a game against the Minnesota Twins on August 17, 1975, entering the game in the ninth inning as a pinch-hitter for Boog Powell. Facing Bill Campbell, he lined out to the shortstop.

After his callup to the big leagues, he played seven games that season. He got his first major-league hit on August 22, a single, against Kansas City pitcher Paul Splittorff.

At the conclusion of the season, Cerone returned to Seton Hall to finish his education degree, which included his student-teaching requirement. The Indians had wanted him to play winter ball in Mexico. “In Cleveland they said, ‘What do you think that degree is going to do for you? You don’t need that,’” Cerone said. “I said, ‘I’m going to need that degree for the rest of my life.’ Plus, it was a promise I made to my parents. I wanted to be a college graduate. Unfortunately, a lot of guys who sign as juniors don’t get that opportunity. To me it was very important.”15

Cerone spent most of the 1976 season playing in Toledo, Cleveland’s Triple-A affiliate in the International League. That December 6, he was traded along with John Lowenstein to the Toronto Blue Jays, a team that had been awarded an American League expansion franchise to begin play in 1977.

Cerone was named the starting catcher for Toronto’s inaugural game on April 7, 1977. Amid wintry conditions at Exhibition Stadium, he received the first pitch from a Blue Jays pitcher, a fastball, thrown by Bill Singer.

Five days later, he broke his thumb when it was hit by a foul tip off the bat of Detroit Tigers third baseman Aurelio Rodríguez, which sidelined him for more than a month. Upon his return, he was sent to the Charleston Charlies of the International League, where he played in 70 games before being recalled in August. Finishing the season in Toronto, he played in 31 games, hitting only .200. However, he hit his first major-league home run off Texas Rangers right-hander Nelson Briles in his first start after his recall.16

Cerone spent the entire 1978 season in Toronto, splitting time at catcher with Alan Ashby. 1979 saw him take over the catching duties full-time. For the season, he hit .239, slugging 7 home runs and driving in 61. His strength was his work behind the plate, as he continued to show capable handling of pitchers and threw out 41% of baserunners trying to steal.

In August 1979, New York Yankees catcher Thurman Munson tragically died in an airplane accident. On November 1, 1979, the Yankees, needing to replace Munson, traded first baseman Chris Chambliss to Toronto in exchange for Cerone. As difficult as it would be to replace Munson, the Yankees hoped that Cerone would complement his defensive catching skills with a productive bat, which they hoped was exemplified by his .261 batting average in the second half of the 1979 season.17 “He can handle it,” said Yankee coach, former catcher Jeff Torborg. “Rick has matured as a catcher and as a person. He’s aggressive and confident without being cocky.”18

Cerone understood the role he was taking on. “I’m not here to make people forget Munson because they won’t,” he said. “I don’t think the fans are looking for me to replace Thurman, but if I do the job the fans will understand. If they don’t…well I’m not interested so much in what the fans will think, I’m more interested in getting the respect of my teammates. If I have a doubt here, it’s getting the guys to accept me.”19

There were concerns about his youth and inexperience. “I’m only 25,” Cerone said, “but I already have four years in the big leagues. People don’t realize that because I spent three of those years in Toronto.”20 He added, “We had new pitchers coming in every week, it seemed,” he remembered. “They all have good arms, but they were usually wild. You really had to concentrate. It made me a lot better catcher.”21

Cerone, a local boy from just across the Hudson River, was ready for the challenge. “I always wanted to play for the Yankees,” he said. “I never thought it would happen because I wanted it to happen so badly.”22

That first season in New York was a success. Finishing seventh in the MVP vote, he had his best offensive season, playing in a career-high 147 games. He hit .277, slugged 14 home runs and drove in 85; all would be career bests. His defensive metrics remained strong, highlighted by his improved success in throwing out a league-leading 52% of would-be base stealers.

Cerone’s offseason contract negotiation with the Yankees was difficult. Having logged 4½ years of major-league experience, and now eligible for arbitration, he asked for a salary increase to $440,000, up four-fold from the previous year. The team offered $350,000.23 Cerone and the Yankees failed to reach a settlement, so they headed to an arbitration hearing. On February 12, arbitrator Jesse Simons, a New York lawyer and director of the city’s Office of Collective Bargaining, ruled in favor of Cerone. At the time, it was the second-largest salary award in arbitration.24

Following the decision, Yankees principal owner and general partner George Steinbrenner lambasted Cerone for being disloyal. “I don’t enjoy a young guy off one good year who was plucked out of Toronto showing so little regard for me,” said The Boss. “It’s not what I am looking for in my kind of guy. I don’t think Tommy John would do that, or Reggie Jackson or Lou Piniella.”25

Cerone, as expected, was pleased. Working out on his own in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, he said, “I’m extremely happy. Now I can go out and play a very happy round of golf this afternoon.”26

Thus began an up-and-down relationship with Steinbrenner – who, irked at losing the arbitration case, often went out of his way to highlight Cerone’s miscues and failures. He often suggested that the catcher’s future as a Yankee was tenuous. “There are guys here who are on trial, and Rick Cerone is one of them,” Steinbrenner said minutes before the Yankees lost 2-1 to the Milwaukee Brewers to even their best-of-five 1981 American League East divisional playoff at two games apiece.27

A few weeks before and during the playoffs, Cerone pointed out that he had been receiving threats, both by telephone and by telegram. He said the phoned threats had forced him to change his number and that of his parents, who had received one of the calls. He said he had also received calls during road trips. The threats had affected him a “little bit,” he said, adding, “The threats are vague. They never say, ‘I’ll kill you,’ or ‘You’ll be dead.’ They just say things like, ‘I’ll get you.’ What does that mean?”28

After his strong 1980 season, Cerone’s offensive production for the Yankees diminished – broken thumbs curtailed his playing time and his overall physical health was impaired. When healthy, he continued as the #1 catcher through 1982. After the season, the 28-year-old New Jersey native and resident said, “I went in to see George and I made it clear to him that I wanted to stay and he made it clear to me that he wanted me to stay. After that we were never far apart.”29 Ultimately, he signed a four-year, $2.4 million contract to remain a Yankee.

But in May 1982, the Yankees had acquired Butch Wynegar, who continued to split time at catcher in 1983 with Cerone. In 1984, he was relegated to backup catcher behind Wynegar, appearing in only 38 games and batting .208.

After the conclusion of the 1984 season, Cerone was traded to the Atlanta Braves for pitcher Brian Fisher. With this trade, Cerone began an eight-year journey around the major leagues, during which he played for seven teams, including two more stints with the Yankees.

In Atlanta, he split catching duties with Bruce Benedict. He hit only .216, and his defensive statistics were only passable, which didn’t make up for his weak offense. In spring training of 1986, he was traded to Milwaukee for catcher Ted Simmons. Once again, he split catching duties, this time with Charlie Moore; he was eventually released and granted free agency after the 1986 season.

Over the winter, as Cerone sought to continue his career, only Montreal showed interest in signing him. “I felt like last year shouldn’t be the end of the line, that I had a pretty good year in Milwaukee,” he said. “’But my biggest fear was that, if I wasn’t with somebody by the spring, that I would be out of sight and out of mind. I’ve been around 11 years, but I’m not old yet. I’m not ready to give it up.”30

Cerone realized that he had changed from being a regular starting catcher to respected journeyman. “I became a role player, and I understood that,” he said. “I accepted not playing every day. But you have to work twice as hard that way. The regular guy can work through his slumps and failures. But when you get up after not playing for a few days and don’t perform well, they don’t want to hear your excuses.”31

From his home in Cresskill, New Jersey, Cerone reached out directly to the Yankees to see if they would give him an opportunity to make the team. He said, “I called up George to ask if they would consider inviting me to camp. He was super about it. He said they had already turned down some other people and that it wasn’t their policy to do that, but that he would make an exception for me. All I wanted was an invite. Within a week’s time, all this happened. I couldn’t believe it.”32

Not only did Cerone make the squad, he also became the primary catcher for Yankee manager Lou Piniella. He hit .243 and played his typically good defense. In 1988, after the Yankees had fired Piniella, they rehired Billy Martin as their manager. Cerone was embroiled in a three-way battle with Don Slaught, the previous year’s backup catcher, and Joel Skinner for two open catching positions. On April 4, 1988, one day before their season opened, the Yankees released Cerone. Although he had batted just .200 in his 30 spring training at-bats, Cerone reacted angrily to the decision, particularly directing his criticism at Martin.

Cerone had played under Martin in 1983, and he said that when Martin was named manager for a fifth time that past October, “I felt I’d be in trouble.”33 During the spring, the Yankees had unsuccessfully tried to trade Cerone, so they asked him to go to their Triple-A affiliate in Columbus. “’I sure wouldn’t go to Columbus to help their situation out,” Cerone said before leaving. ‘” If it was a different manager, I’d consider it, but I won’t.”34

Martin insisted that two of the club’s coaches, Jeff Torborg and George Mitterwald, another former big-league catchers, were pivotal in deciding who stayed and who went. Cerone didn’t buy Martin’s contention, and he didn’t blame George Steinbrenner. “I don’t have any hard feelings for Lou or George. They brought me back as a free agent when I didn’t have a job, and somehow, I wound up catching 115 games last year.”35

Eleven days later, on April 15, Cerone latched on with the Boston Red Sox. There he spent the next two seasons splitting time at catcher with Rich Gedman. He played in 186 games total for Boston, batting .255 with seven homers and 75 RBIs. Released by the Red Sox after the 1989 season, he was again signed by the Yankees, who gave him a two-year contract at $600,000 per year. His third stint in the Bronx lasted only one season, during which he played in just 49 games as the backup catcher to Bob Geren. His season was marred when he underwent surgery to repair ligament damage to his left knee, causing him to miss two months.36

Shortly after he cleared waivers, he was signed by the New York Mets, becoming the 42nd player to have worn both the Yankees and Mets uniforms.37 The Yankees were obligated to cover the second year of Cerone’s two-year contract, so that limited the Mets’ financial responsibility to the league minimum, then $100,000. “I wanted to play for the Mets,” Cerone said from his Cresskill home. “I wanted to play for a contender. And I wanted to stay close to home.”38

He had a good season with the Mets, hitting .273 and remaining a successful defensive catcher. His 63 starts and 573 innings behind the plate were the most for any of the team’s catchers, But, by then 37 years old, he was granted his release by the Mets after the conclusion of the 1991 season.

As he opted to continue his career, Cerone signed with the Montreal Expos in February 1992, becoming the 21st major-leaguer to play for both Canadian teams.39 At 38, he appeared in only 33 games that season, as he was the backup to veteran Gary Carter; he was released by the Expos on July 16.

By August, Cerone had decided to retire. “My first life is over,” he told The Record of Hackensack, New Jersey. “My other eight lives are about to begin.” Cerone was rational about retirement and knew this day would come. “I started thinking about what I’d do after baseball in 1985.”40

Living in New Jersey, he tackled many ventures. He invested in a Kansas City Royals farm team, the Wilmington (Delaware) Blue Rocks. He served as an advance scout for the Yankees. He worked with Nicholas De Carlo, then his father-in-law, learning about the construction business. (Cerone and Michele De Carlo were married on October 29, 1983.41 By 1999, they were divorced.) He ventured into real estate and sports marketing and made public speaking engagements. In 1996 and 1997, he served as a color commentator for the Yankees’ broadcasts on WPIX.

In 1998, he joined the Baltimore Orioles’ broadcast team, which became a one-year stint away from home. “I made a huge mistake,” Cerone said of leaving the Yankees’ television booth to call games in Baltimore. “[The Orioles] called out of the blue, so they were hiring an announcer, not a former player, and maybe it was a little bit of an ego thing on my part … I think (George Steinbrenner) resented me for doing that. He was tough, but he took care of people. I can’t fault him, he valued loyalty. I wish I had never done that.”42 The work in Baltimore was intense, a daily grind that included pregame and postgame work, and kept him away from his New Jersey home.

In 1998, Cerone founded the Newark Bears. a member of the newly formed Atlantic League, an independent baseball circuit. In his effort to revive baseball in his hometown, he received a $34 million boost from Essex County to build a new stadium downtown, hoping it would help spur the revival of inner Newark. After six years of working to build interest in the team, he was exhausted and frustrated and sold the team. “My vision was to help bring people back to Newark, which the stadium has done,” he said. “But what I didn’t calculate was the competition for the entertainment dollar in North Jersey. Still, there are millions of people within a 15-mile radius of the ballpark. I don’t know, I don’t have the answer. I got a little tired.”43 He added, “With the Bears, we have a great product. We’ve had big-name players like Rickey Henderson. We’ve won the league championship and should have won another, and we have great sponsor support. The only thing missing in Newark are the bodies. I don’t know why.”’44

In August 2020, it was announced that Cerone would be inducted into the National College Baseball Hall of Fame, as part of a 12-member class including Jason Varitek and Paul Molitor. “Seton Hall University and Seton Hall baseball are very proud of Rick Cerone’s induction into the National College Baseball Hall of Fame,” said Seton Hall baseball head coach Rob Sheppard, whose father, Mike Sheppard, Sr., had been Cerone’s head coach beginning with his sophomore season. “Rick is one of the best players to ever wear a Pirate uniform. Rick has been a great ambassador of our program and continues to be faithful supporter of our program.”45

Though Cerone’s career at Seton Hall catapulted him to the major leagues, he claimed that he loved playing college baseball more than playing pro ball. Crediting his Jersey roots, he commented that along with owning the Newark Bears, the College Baseball Hall of Fame is his greatest accomplishment.46

In retirement, Cerone described himself as a former ballplayer who has always contributed his time and efforts to supporting others, especially in his native New Jersey. He resides in West Palm Beach, Florida, and spends his summers down the Jersey Shore, to be near his three adult daughters – Jessica, Carly, and Nikki. His first grandchild was born in 2020.

Last revised: March 3, 2025

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Rick Cerone for interviews on November 9, 2021.

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Rosemary ‘Toots’ Cerone,” Legacy.com, December 9, 2014.

2 Rick Cerone, telephone interview, November 9, 2021.

3 Our School – Essex Catholic, essexcatholiceagles.com

4 Rick Cerone BB, NJsports.com, https://www.njsportsheroes.com/rickceronebb.htm

5 Rick Cerone, telephone interview, November 9, 2021.

6 Jerry Carino, “Rick Cerone is a rarity in the College Baseball Hall of Fame, and darn proud of it,” Asbury Park Press, August 11, 2020.

7 Robert Fallo. “Pirate baseball great Cerone inducted to Hall of Fame,” Setonian, August 29, 2020.

8 News 12 Staff. “Former Seton Hall baseball star Rick Cerone inducted into College Baseball Hall of Fame,” News 12 Long Island, September 4, 2020.

9 “Former Seton Hall baseball star Rick Cerone inducted into College Baseball Hall of Fame.”

10 Carino.

11 Carino.

12 Carino.

13 Carino.

14 Carino.

15 Carino.

16 Kevin Glew, “Five things you might not know about…Rick Cerone,” Cooperstowners in Canada,com, https://Five things you might not know about . . . Rick Cerone – Cooperstowners in Canada, May 19, 2021.

17 Phil Pepe. “Heat’s on Cerone,” The Sporting News, May 30, 1980, 7.

18 Pepe

19 Pepe.

20 Pepe.

21 Pepe.

22 Pepe.

23 Joseph Durso, “Fisk Declared Free Agent; Cerone Wins Salary Case,” New York Times, February 16, 1981: A19.

24 Durso.

25 William Julianom “Yankees’ Arbitration History, or Why Rick Cerone Was Ungrateful and Don Mattingly Couldn’t Play Little Jack Armstrong,” https://captnsblog.wordpress.com/2010/11/24/yankees-arbitration-history-or-why-rick-cerrone-was-ungrateful-and-don-mattingly-couldnt-play-little-jack-armstrong/

November 20, 2010.

26 Durso.

27 Logan Hobson, “Rick Cerone was a man on his way to…,” UPI archives, October 10, 1981.

28 Associated Press, “Threats to Cerone,” New York Times, October 12, 1981: C4.

29 Murray Chass. “Cerone will sign 4-year Yankee Pact,” New York Times, November 4, 1982: D23.

30 Michael Martinez,. “Yankees Sign Cerone,” New York Times, February 14, 1987: 47.

31 Jan Hoffman. “PUBLIC LIVES; Cerone’s Back in the Minors, and Loving It,” New York Times, July 8, 1999: B2.

32 Hoffman.

33 Michael Martinez, “Cerone and Royster Let Go,” New York Times, April 5, 1988: A19.

34 Martinez, “Cerone and Royster Let Go.”

35 Martinez, “Cerone and Royster Let Go.”

36 Claire Smith, “Cerone Is Happy to Join Mets After Weak Year with Yanks,” New York Times, January 22, 1991, B11.

37 Smith.

38 Smith.

39 Glew.

40 Craig Murder, “#Card Corner: 1978 Topps Rick Cerone,” https://baseballhall.org/discover/CardCorner-1978-Topps-Rick-Cerone

41 “Michele De Carlo a Bride,” New York Times, October 30, 1983: 70.

42 Matt Gagne, “Former Yankees catcher Rick Cerone still talks one hell of a game,” New York Daily News, April 9, 2018.

43 Terry Golway,. “If You Build It, Will They Come?” New York Times Sunday Magazine, July 13, 2003: 48.

44 Golway.

45 Seton Hall University – 1982 Hall of Fame, SHU Press, August 6, 2020.. https://shupirates.com/news/2020/8/5/cerone-gets-the-call-to-the-national-college-baseball-hall-of-fame

46 News 12 Staff, “Former Seton Hall baseball star Rick Cerone inducted into College Baseball Hall of Fame,” News 12 Long Island, September 4, 2020.

Full Name

Richard Aldo Cerone

Born

May 19, 1954 at Newark, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.