Carl Yastrzemski

Saddled with the burden of replacing one of baseball’s legendary players, Carl Yastrzemski carved out his own iconic Hall of Fame career, eventually escaping Ted Williams’ extraordinary shadow to win three batting titles and seven Gold Gloves, and earn 18 All-Star selections. In Boston, where he played the entirety of his 23-year career, he is remembered especially for his Triple Crown season that led Boston to its Impossible Dream in 1967.

Born August 22, 1939, in Southampton, New York, Carl Michael Yastrzemski came of age in nearby Bridgehampton, Long Island (population 3,000) where he often played alongside his father in local semipro games. Yaz’s father Karol Yastrzemski (the name was Anglicized to Carl) and his uncle Tommy owned an inherited 70-acre potato farm, their work a “legacy from Poland, folks coming over here and doing what they knew from the old country.”1

In his first of two autobiographies, Yaz wrote, “I’m told that when I was 18 months old my dad got me a tiny baseball bat, which I dragged around wherever I went, the way other babies drag blankets or favorite toys. I vaguely remember playing catch with him as a very small boy, but my first clear memory is hitting tennis balls in the back yard against his pitching after supper every night when I was about six. Later we played make-believe ball games between the Yankees and the Red Sox, my two favorite teams…”2

Yaz’s dad loved baseball. He might have tried to make it in baseball himself, reportedly having offers from both the Dodgers and the Cardinals, but was “reluctant to leave the potato fields of Long Island to try baseball during the Depression.”3 Before Carl was born, Carl Yastrzemski Sr. actually formed a semipro baseball team, the Bridgehampton White Eagles; he played shortstop and managed the team. It was almost entirely a family team, with Carl Sr.’s four brothers on the team, as well as two brothers-in-law and three cousins. The team played on Sundays, and did so for years. By the time Carl himself was seven, he was the team’s batboy, his first “job” in baseball. He first played for the team at age 14 – young for a semipro player. Even at age 40, Carl’s father was still “the guts of the ball club, a good shortstop and the best hitter of the team.”4 His father played with drive and determination, but channeled his baseball ambitions into his son Carl. Still playing (and out-hitting his son) at age 41, Carl’s dad was doing it for his son. The younger Yaz wrote, “I could tell the only reason he played was on account of me, just as that had been the only reason he kept the White Eagles alive for so long.”5 From the very date Carl signed his first pro contract, the elder Yastrzemski never played again, but the memory lasted. “I loved his spirit and intensity when I played alongside him.”6

Some of Carl’s teammates with the Boston Red Sox saw the influence of Carl’s father in his son’s drive for success. Former Red Sox catcher Russ Gibson remembered one time early on: “Yaz and myself, and two other guys, shared an apartment in Raleigh [North Carolina] when his dad came for a visit. We were all just starting out, but Yaz was hitting about .390 at the time. We all went off to play golf while Yaz visited with his father. When we got back, all his things were gone. When I asked Yaz what had happened, he said, ‘My dad thinks I’m distracted living with you guys. He’s moved me into an apartment by myself.’”7

Carl’s father was quite a man himself. Scouted during the Depression, Carl Sr. never played professionally but he was a fierce advocate for his son.

Yaz attracted a lot of attention playing ball on Long Island. His last couple of years in high school, he played semipro ball for Lake Ronkonkoma, a team based about 60 miles from home. His father played for this team, too, always after work on the farm was done. It was around this time that Carl’s father began to boost him as a hitter more than as a pitcher – even though at a major-league tryout camp for the Milwaukee Braves, Carl faced nine batters and struck out all nine. The younger Yaz had the chance to sign on with a major-league team before he even got out of high school, but Carl’s dad had his eyes set on a sizable bonus and had been prepared to turn down offers he saw as inadequate. Come his senior year, Carl’s dad told his high school coach that Carl would not be playing football that year – there was too great a risk of injury, and that might hamper his development as a baseball player.

While Yaz was still a senior in high school, the New York Yankees made a pitch. Though not allowed to sign Yastrzemski to an actual contract until after he graduated high school, Yankees scout Ray Garland was still welcomed into the household to talk hypotheticals. He traded bonus numbers with Carl’s father, writing $60,000 on a piece of paper at the dining room table. Carl’s dad wrote out $100,000. Garland reacted dramatically, flipping his pencil in the air and hitting the ceiling as he exclaimed, “$100,000? Are you crazy? The Yankees will never pay that.” The Yankees never got the opportunity, despite even owner Dan Topping becoming involved. The elder Yaz told Garland, “Nobody throws a pencil in my house. Get the hell out and never come back.”8 That was it for the New York Yankees.

Red Sox scout Frank “Bots” Nekola had had his eye on Carl since he was a sophomore in high school. He never threw any pencils in the Yastrzemski household, but he wasn’t coming up with $100,000, either, and so Carl’s father sent his son off to college. They’d fielded full scholarship offers from a number of colleges, but chose Notre Dame, where he played on a scholarship that was half baseball and half basketball. Yaz completed his freshman year, without playing on the varsity team, but then the offers got more serious, even exceeding $100,000. The Red Sox didn’t make the largest offer, but the admiration of the local parish priest for Tom Yawkey counted for a lot, and Yaz’s father wanted him playing for an East Coast team, not too far from home. Yaz signed with the Red Sox in November 1958 for a $108,000 bonus, and their agreement to cover the rest of his college education. Sox GM Joe Cronin then met Yaz for the first time – and saw a 5’11”, 160-pound kid. He couldn’t help himself, blurting out, “We’re paying this kind of money for this guy?”9 Carl went back to finish up the fall semester at Notre Dame; after signing the six-figure contract, Yaz’s father increased his son’s weekly allowance from $5 to $7.50 a week.10

The first of many spring training camps was 1959 and Carl was assigned to the Raleigh Capitals in the Carolina League, a Class B team. The team switched him from shortstop to second base. He was struggling at the plate until manager Ken Deal got him in the box and told him to move up on the plate so he wasn’t lunging at balls on the outer half of the plate. He says he batted close to .400 for the rest of the year. After Raleigh’s season was over, he was invited to come to Fenway Park, not to play ball but to look in on the ballclub. Ted Williams greeted him and told him, “Don’t let them screw around with your swing. Ever.”11

Yaz then went on to Minneapolis to join the Millers as they entered the American Association playoffs. Researcher Wayne McElreavy notes that, oddly, Yaz was ineligible and there was a protest, but the league did not force a forfeit. The first time he faced Triple-A pitching, he went 7-for-18 in the six games it took to win the title. And then he traveled to Cuba to play the Havana Sugar Kings for the International League championship. Fidel Castro came to the ballpark, arriving by helicopter and landing near second base. The Sugar Kings won in the seventh game, but it was the last time (until the Baltimore Orioles played an exhibition game in 1999) that an American pro team played in Cuba.

In January 1960, Carl married Carol Casper. In February, they headed to Scottsdale so Carl could train with the big league ballclub. Carl lockered right next to Ted Williams, but Ted rarely spoke to him. The main thing Carl learned from 41-year-old Teddy Ballgame was how hard he prepared himself to play ball. The Red Sox had Pete Runnels at second base (Runnels would win the batting title in 1960), so they sent Carl back to the minors for one more year, the purpose being to train Yaz to play left field and get him ready to take over for Williams, the expectation being that Williams would probably retire after the 1960 season. Yastrzemski batted .339 for Minneapolis, just missing out on the title by three points, and began to show some skill in the outfield, recording 18 assists.

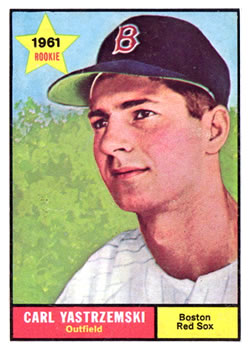

Ted Williams retired. Both the baton and the burden of replacing the great slugger were passed to Carl Michael Yastrzemski. Opening day 1961 was April 11, at Fenway Park, and there was Yastrzemski playing left field and batting fifth. Replacing Williams in left field and in the hearts of Boston Red Sox fans was a Herculean task for any player, let alone a 21-year-old with two years of professional baseball experience. Williams was a larger-than-life figure on and off the field, and had played for the Red Sox since 1939. Yaz singled to left his first time up, but ended the day 1-for-5. His first and second homers came in back-to-back games on May 9 and 10, but all in all, he struggled at the plate. “I started off very slow. I actually think that was on account of Ted. I was trying to emulate him – be a home run hitter and not be myself: just an all-around player. I could never be a Ted Williams as far as hitting was concerned.”12 When Yaz struggled, the Sox asked Ted to interrupt his fishing and come pay a visit. Williams complied, visited, and watched Yaz take extra batting practice. He told Yaz he had a great swing and to just go out and use it. “I think what dawned on me was that there can be a great swing that is not a home run swing at the same time.”13

Yaz batted .266 in his rookie year, with 11 homers and 80 RBIs, a good first year once he’d gotten back on track. There was no sophomore slump: Yastrzemski boosted his totals to .296, with 19 homers (and 43 doubles) and 94 RBIs. His third year, he made the All-Star team for the first time, and improved dramatically again, to win the American League batting championship with a .321 mark. He led the league in base hits, doubles, walks, and on-base percentage. All the while, Yastrzemski was improving in left field, honing the solid defensive play that he is remembered for today.

He continued to add to his totals, again making the All-Star team in 1965 and 1966. In 1965, he accomplished one of the rarest of hitting feats – Yaz hit for the cycle in the May 14 game, with an extra home run thrown in for good measure. Later that year, Yaz even faced Satchel Paige, who had come back to pitch one last time at age 59. Paige threw three innings and gave up only one hit – to Carl Yastrzemski. Yaz’s first six seasons in the major leagues had established him as one of the star players in the game. But his 1967 season would propel Carl Yastrzemski to a place among the elite players in the history of the game.

“One of the big differences in 1967,” Yaz recalled, “is that I was able to work out the preceding winter. In earlier years, I was finishing up my college work. But I had completed my degree at Merrimack College so I had time to focus on my conditioning. I reported to spring training in great shape.”14

By the time the 1967 All-Star Game rolled around, Yaz was among the top five in the American League in batting average, home runs, and runs batted in. The Red Sox were only six games out of first place at the All-Star break, and it was clear that the team had as good a shot at the American League pennant as anyone.

The 1967 Red Sox held New England fans spellbound all summer and into the fall, as they battled for first place in the most exciting pennant race in American League history. Their thrilling win over the Minnesota Twins on the last day of the season touched off one of the great celebrations in Boston history. While a different Red Sox hero seemed to emerge daily, the one constant was Yaz.

Former teammate George Scott remembers it this way, “Yaz hit 44 homers that year, and 43 of them meant something big for the team. It seemed like every time we needed a big play, the man stepped up and got it done.” In the final 12 games of the season – crunch time – Carl Yastrzemski had 23 hits in 44 at-bats, driving in 16 runs and scoring 14. He hit ten homers in his final 100 at-bats of 1967. He had ten hits in his last 13 at-bats, and when it came to the last two games with the Twins, with the Sox needing to win both games to help avert a tie for the pennant, Yaz went 7-for-8 and drove in six runs.

Yaz was no slouch in the playoffs, either, batting an even .400 (10-for-25) with three home runs and five RBIs in the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals. The storybook season came to an end when the St. Louis Cardinals won the World Series in Game Seven, but Carl Yastrzemski’s place was indelibly etched in baseball folklore. Yaz came within one vote of a unanimous selection as the Most Valuable Player of the American League. He was selected by Sports Illustrated as the “1967 Sportsman of the Year” at year-end. And he achieved baseball’s Triple Crown, leading the American League in batting (.326), runs batted in (121), and home runs (44). In all the baseball seasons that followed, no player had been able to match his Triple Crown feat until Miguel Cabrera did so in 2012, 45 years later.

Yaz also led the league in hits (189), runs (112), total bases (360), and slugging percentage, not to mention on-base percentage. His On-Base plus Slugging (OPS) was 1.040. How did a Triple Crown winner who brought his team to the pennant miss the MVP by one vote? One voter cast his first-place ballot for Cesar Tovar of the Twins. Tovar batted .267, had six homers to Yaz’s 44, and drove in 47 runs to Yaz’s 121!

The next year, 1968, Yaz won his third batting title, with a .301 mark. This was, for sure, the Year of the Pitcher, and Yaz was the only batter in the league to crack .300, 11 points ahead of runner-up Danny Cater. Only four batters hit .285 or above.

Between 1965 and 1979, Yaz was named to 15 consecutive All-Star teams. The game he remembers best is the 1970 All-Star Game held in Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati. Yaz had four hits, to go along with a run scored and an RBI to earn him MVP honors that year, even though his AL team lost to the NL in 12 innings. He and Ted Williams [1946] are the only two American Leaguers with four hits in an All-Star Game. When asked about this record Yaz, never one to focus on personal statistics, responded, “I never knew that before. To tell you the truth, I was so sick of losing to the National League that I didn’t pay much attention to that stuff.”15

It is sometimes written that Yaz had a “career year” in 1967, but never again approached that standard. It should be noted that in 1970 he led the American League in runs scored, on-base percentage, total bases, and slugging percentage; and – when rounded – he was .0004 out of the lead for the batting title. When coupled with his all-time high of 23 stolen bases, you have a year that would have been a career year for almost any other player.

Those 23 stolen bases made him only the second player in Red Sox history to steal more than 20 bases and hit more than 20 home runs in a single season. Former All-Star outfielder Jackie Jensen was the first Red Sox player to achieve this combination in 1954, and Jensen duplicated this feat during the 1959 season. Only five other Red Sox players have achieved this standard since.

In February 1971, Carl Yastrzemski signed a three-year contract that was reported to pay him $500,000 over the three seasons. At that time his contract was the largest in baseball history.

The year 1972 was a frustrating one. The season started late, due to struggles between players and owners. Teams agreed to simply play out the schedule without worrying about whether one team played more games than another. As fate would have it, the Red Sox entered the final three games of the year playing the Tigers in Detroit. There was no chance of a playoff tie. The Tigers had a record of 84-69 going into the October 2 game, and the Red Sox were a marginally better 84-68. Whichever team won two of the three games would win the pennant. The Tigers took a 1-0 lead in the first game, but Yaz doubled in the top of the third to tie it – and the Red Sox would have scored at least one more run (with Yaz safe at third with a triple) except that Luis Aparicio stumbled after rounding third and retreated to the bag where he met up with the oncoming Carl, who was called out. One never knows what might have been, but this was a pivotal play and the Red Sox lost the pennant by a half-game.

Yaz had a subpar year in 1975, batting just .269 with 14 homers and 60 RBIs, but his play throughout the postseason reminded fans that he had always been at his best in clutch situations throughout his career. His stellar play in the field and at bat carried over to the American League Championship Series against Oakland (he was 5-for-11, with a home run and two RBIs) to the World Series against the Cincinnati Reds. Although the Red Sox lost to the Reds in seven games in one of the greatest World Series ever played, Yaz had scored 11 runs and batted .350 during the ten postseason games. As in 1967, the Red Sox fell just short.

From 1976 to 1983, Carl Yastrzemski made the American League All-Star team six times. On July 14, 1977, he notched his 2,655th hit, moving past Ted Williams as the all-time Red Sox base hit leader. In 1979, he became the first American Leaguer to accumulate both 400 homers (he reached the plateau on July 24) and 3,000 lifetime hits (his September 12 single off New York’s Jim Beattie was #3,000). Back on June 16, he’d banged out his 1,000th extra base hit.

On October 1, 1983, the next-to-the-last game of the season, 33,491 of the Fenway Faithful gathered to pay tribute to Carl Yastrzemski. The pre-game ceremony lasted for about an hour, and then came Yaz’s turn to speak. After 23 years of never flinching in a pressure situation, Yaz broke down and cried when he stepped to the microphone. Once he regained his composure, he asked for a moment of silence for his mother and for former Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey. After thanking his family and everyone connected with the Red Sox, he finished with the words, “New England, I love you.”

Carl Yastrzemski had played in 3,308 major-league ballgames – the record until Pete Rose topped it the next year – and played for 23 years for one team: the Boston Red Sox.

A few months after Carl retired, his son Carl Jr. was drafted by the Atlanta Braves in the third round of the January 1984 draft.. Known as “Mike,” the younger Yastrzemski played five years of minor-league ball, making it all the way to a couple of years of Triple A, but not to the majors. He came back to work in Massachusetts but died of a heart attack in September 2004 at the age of 43.

Mike’s son Mike was drafted by the Orioles in 2013 and as of this writing in the summer of 2014, is playing in his second year of minor-league ball.

In January of 1989, in his first year of eligibility, Carl Yastrzemski was elected to Baseball’s Hall of Fame. His vote total that year was among the highest recorded in the history of the Hall of Fame. On August 6, 1989, the Red Sox retired his uniform number and it still hangs today, #8, overlooking Fenway’s outfield.

The baseball careers of Ted Williams and Carl Yastrzemski are inexorably linked. Their paths crossed directly for the last time when they were introduced before the 1999 All-Star Game at Fenway Park as two of the 100 greatest baseball players of the 20th century. The crowd reaction when Yaz was introduced shook the ballpark to its ancient foundations. The response of the crowd when Ted was driven from the far reaches of center field to a spot near the pitchers’ mound nearly equaled the decibel count of the jet fly-by following the National Anthem. At the home opener in 2005, Carl Yastrzemski and Johnny Pesky joined to raise the 2004 World Championship banner that flew over Fenway throughout the 2005 season.

Carl Michael Yastrzemski: the man we affectionately call Yaz.

A version of this biography appeared in “’75: The Red Sox Team That Saved Baseball” (Rounder Books, 2005; SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Cecilia Tan. It also appeared in “The 1967 Impossible Dream Red Sox: Pandemonium On The Field” (Rounder Books, 2007), edited by Bill Nowlin and Dan Desrochers.

Sources

Personal interviews with Carl Yastrzemski by Herb Crehan in May 1999.

Crehan, Herb, Red Sox Heroes of Yesteryear (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Rounder Books, 2005).

Total Baseball

Yastrzemski, Carl and Gerald Eskenazi, Yaz: Baseball, the Wall, and Me (New York: Doubleday, 1990).

Yastrzemski, Carl with Al Hirshberg. Yaz (New York: Viking Press, 1968).

Notes

1 Yaz: Baseball, the Wall, and Me, 7.

2 Yaz (1968), 37.

3 Yaz: Baseball, the Wall, and Me, 1, 8.

4 Yaz (1968), 46.

5 Yaz (1968), 50, 51.

6 Yaz: Baseball, the Wall, and Me, 11.

7 Personal interview with Herb Crehan, 1999

8 Yaz: Baseball, the Wall, and Me, 19.20.

9Yaz: Baseball, the Wall, and Me, 39.

10 Yaz (1968), 72. In the 1990 autobiography, Yaz remembers the increase being from $2 to $3. See page 40.

11 Carl Yastrzemski, Yastrzemski (New York: Rugged Land, 2007), 54.

12 Jim Prime and Bill Nowlin, Ted Williams: The Pursuit of Perfection (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2002), 102.

13 Ibid.

14 Personal interview with Herb Crehan, 1999

15 Ibid.

Full Name

Carl Michael Yastrzemski

Born

August 22, 1939 at Southampton, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.