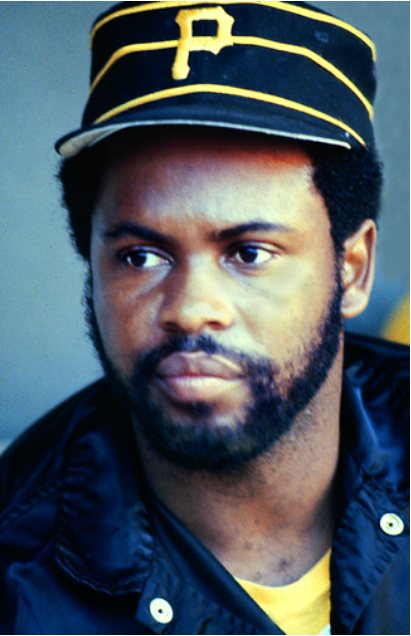

Bill Madlock

If one had to summarize Bill Madlock’s career in song, the best two numbers to choose would be Noël Coward’s “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” and Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing if You Ain’t Got That Swing.” The former because “Mad Dog” was his nickname, the latter because it took only one cut for a scout to see that Madlock did indeed have that swing. He also had a lot of intestinal fortitude, overcoming a difficult upbringing to become a four-time batting champion and the owner of a World Series ring.

If one had to summarize Bill Madlock’s career in song, the best two numbers to choose would be Noël Coward’s “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” and Duke Ellington’s “It Don’t Mean a Thing if You Ain’t Got That Swing.” The former because “Mad Dog” was his nickname, the latter because it took only one cut for a scout to see that Madlock did indeed have that swing. He also had a lot of intestinal fortitude, overcoming a difficult upbringing to become a four-time batting champion and the owner of a World Series ring.

Bill “Mad Dog” Madlock was born on January 2, 1951, in Memphis, Tennessee. His father had abandoned his mother, so she gave Madlock to her mother, Annie Polk, to raise when he was less than one month old. He and Annie moved to Decatur, Illinois, when he was 2, and his aunt and uncle, Sarah and Wardie Sain, helped bring him up.

Madlock was well “Iked” at Eisenhower High School in Decatur, earning nine sports letters. As an all-state halfback, he once scored five touchdowns in a game, each on a run of 50 yards or more. In basketball, he made the all-Capitol Conference second team. More than 100 colleges sent representatives to scout Madlock for a possible football scholarship, but simple self-preservation convinced him to focus on baseball.

“I didn’t want to have 6-foot-5, 250-pound guys bearing down on me, so I decided to play baseball,” he said.1

The year 1969 was eventful for Madlock. He married Cynthia Johnson while still in high school.2 He was drafted in the 11th round of that year’s amateur draft as a shortstop by the St. Louis Cardinals, but didn’t sign because he thought his playing time would be limited with Dal Maxvill manning the position for the big club. He also enrolled at Southeastern Iowa Community College in Keokuk, Iowa, to hone his baseball skills. That summer, after rejecting the Cardinals, he was back playing in Decatur when legendary baseball scout Ellsworth Brown, who was working for the Washington Senators at the time, took a different route home one night, thus changing Madlock’s life forever.3

“I’d been down in southern Illinois, and I was driving home to Beason,” said Brown. “Usually I go to Lincoln and back down the highway. This time I took a back road from Decatur through Chestnut, and I saw a ballgame going on right there in Beason. Lincoln’s Legion club was there against Decatur. It was the last inning. I saw this kid by the name of Bill Madlock swing one time, and I said, ‘Boy, he’s got that quick bat.’ I went to Lincoln’s coach, John West, and said, ‘How’d that kid do the last time up?’ West said, ‘He reached that fence out there.’”4

Brown passed that information on to the Senators, who drafted Madlock in the fifth round of the 1970 January secondary draft. After signing him on May 25, Washington sent him to the Geneva Senators of the Class-A (short season) New York-Pennsylvania League, where he hit a modest .269 with 6 home runs and 29 RBIs in 66 games. Madlock’s time in Geneva was stressful, because he had difficulty finding accommodation; no one wanted to rent to a black family. Nonetheless, the National Association of Baseball Writers voted him to the Class-A All-Star team as a shortstop. This feat was particularly impressive because the team included players from the Florida State, Carolina, and Western Carolina Leagues, as well as the New York-Pennsylvania League.

The Senators promoted Madlock to their Double-A affiliate, Pittsfield of the Eastern League, for 1971. He made an impression there early, securing the victory in the team’s second game with a two-run homer in the top of the 11th inning. The home run atoned for two errors he made earlier in the game, but it was also a harbinger of a disappointing season, in which he hit .234 with 10 home runs and 37 runs batted in.

“I would not have bitched if they had released me then and there,” said Madlock. “I was awful. I figured the quickest way to the majors was to be an infielder who hit home runs, when actually that was the quickest way back to Decatur.”5

Perhaps he was being tough on himself because he played and starred in the Eastern League All-Star game, going 3-for-5 with one RBI and three runs scored as he led his American Division team to a 5-2 win over the National Division All-Stars.

Madlock was also right in the middle of a disturbing incident near the end of the season. A huge brawl erupted in the seventh inning of an August 7 game between the Senators and the visiting Waterbury Pirates when Madlock proved he was no chicken by charging the mound after nearly getting beaned by pitcher Bob Cluck. What followed was a vintage NHL-style donnybrook that lasted almost half an hour, with some players bringing bats into the melee (The Berkshire Eagle said that nobody connected with them). Things got so out of hand that the ballpark announcer began playing the national anthem in an effort to restore order.

Madlock was suspended for the remainder of the season, but was reinstated after two weeks. Three other players, two from Waterbury and one from Pittsfield, were only suspended for three games each. Madlock returned with a flourish, going 3-for-5 in his first game back and making a great backhand stop at third base to prevent a hit.

The next rung on Madlock’s climb to the majors was a mile high, when he began the 1972 season, with the Denver Bears of the Triple-A American Association. He didn’t do well, playing only 26 games and hitting .213 with one homer and 9 RBIs before being sent back to Pittsfield. This move proved beneficial to Madlock’s career because Pittsfield manager Joe Klein gave him the at-bats he needed to learn how to be more selective. Madlock played in only 42 games for Pittsfield that year, but his average exploded to .328 with 4 home runs and 26 RBIs.

That extra time in Pittsfield created a terror at the plate, as Madlock moved up in 1973 to the Texas Rangers’ new Triple-A affiliate, the Spokane Indians of the Pacific Coast League.6 He hammered PCL pitching to the tune of a .338 batting average, and showed substantially improved pop with 22 homers and 90 RBIs. The home-run total proved to be the highest of his career.

Those numbers demanded a call-up to the majors, and that’s exactly what happened that September. Madlock made his major-league debut with the Rangers on September 7, going 2-for-3 with a walk and two runs scored while playing an errorless third base in a 10-8 win against the eventual world champion Oakland A’s. His first home run came September 17 off Jim Kaat of the White Sox, a two-run shot in the first inning of a 10-3 win. Overall, Madlock hit a most promising .351 in 77 at-bats.

The 1973 Rangers had the worst record in the major leagues at 57-105. They scored the fewest runs (619) and had the highest team ERA (4.64) in the American League. Since they had to improve in every facet of the game, they flipped a coin and decided to start with pitching. To do that, they sent Madlock and utility player Vic Harris to the Chicago Cubs for future Hall of Famer Ferguson Jenkins on October 25, 1973. After six straight 20-win seasons, Jenkins had gone 14-16 for the Cubs in 1973 and was starting to get up there at age 30. Madlock, of course, was an untested rookie.

The trade worked out well for both teams. Jenkins won 25 games for Texas in 1974, while Madlock, hit .313 with 9 home runs and 54 RBIs for the Cubs, despite the pressure of following Cubs legend Ron Santo at the hot corner. Madlock also finished third in Rookie of the Year voting behind Bake McBride of St. Louis and Greg Gross of Houston.

He also got into a fight with Cardinals catcher Ted Simmons as a result of the antics of St. Louis relief pitcher Al “The Mad Hungarian” Hrabosky. Hrabosky was famous for psyching himself up and annoying batters by taking a ball, rubbing it vigorously while walking off the mound toward second base, talking to himself and/or the goulash gods, and then firing it into his glove before returning to the mound to pitch with steam snorting out of his nose.

In a September 22 game at Busch Stadium in St. Louis, Madlock led off the ninth inning with Hrabosky on the mound. After Hrabosky finished his behind-the-mound ritual and returned to the hill, Madlock stepped out of the batter’s box. Home-plate umpire Shag Crawford told Hrabosky to pitch, which he did. Crawford called an automatic strike. Realizing what was happening, Madlock ran back to the plate just in time to duck a high hard one. As chaos ensued around home plate, Madlock and Simmons began jawing at each other and the fight was on. The dugouts emptied, but the dustup was over in a few minutes. Ironically, and perhaps appropriately, that was also the day that the Cardinals retired Dizzy Dean’s number 17.

“Madlock came back to the plate and just stood there staring at me,” said Simmons. “I asked him, ‘What are you looking at?’ and he said, ‘Nuts to you.’ “Then I went ‘wham.’”7

Whether Madlock said “nuts to you” or something less printable is a mystery lost to the ages. What can’t be refuted is the fact that he won his first batting title in 1975 with a .354 batting average, 182 hits, 7 home runs, and 64 RBIs, despite missing most of September with a bruised thumb. He also made his first All-Star team, which was no mean feat in an era that included Mike Schmidt and Ron Cey among National League third basemen. He showed that he earned the nomination by getting the game-winning hit, a bases-loaded two-run single in the ninth, as the National League defeated the American League 6-3 in the All-Star Game. He shared the outstanding-player award for the game with Mets pitcher Jon Matlack.

Madlock really blew it in September. Unfortunately, he overblew it, losing to Johnny Oates of the Phillies in the second round of the Joe Garagiola/Bazooka Bubble Gum Blowing contest. The competition was a light-hearted creation for the television show The Baseball World of Joe Garagiola, which included one representative of each team except the Detroit Tigers and Pittsburgh Pirates.8 This was just one example of Madlock’s lighter and community-oriented side. On September 28 of that year, for example, he and Cynthia were grand marshals for a bike-a-thon in Rolling Meadows, Illinois, to raise money for multiple-sclerosis programs.

This doesn’t mean that Madlock no longer blew his stack. He was fined $100 for throwing his batting helmet during one August game, then another $100 for saying, “Nuts to you” or words to that effect to umpire Art Williams. In September he was fined $250 for lunging at umpire Jerry Dale after being called out on strikes.

The Bill Madlock Bicentennial Brouhaha occurred May 1, 1976, at Candlestick Park in San Francisco. It all started in the third inning when Giants pitcher Jim Barr brushed back Cubs left fielder José Cardenal, who was batting one spot ahead of Madlock. Umpire Paul Runge warned Barr, but Cardenal threw his batting helmet at the pitcher and got ejected for his trouble. Barr then plunked Madlock when he came to the plate and the fun ensued. Madlock headed toward the mound, followed by San Francisco catcher Marc Hill, who was trying to restrain him, but Bill managed to reach around Hill and slug Barr as the benches emptied. Madlock was thrown out of the game after order was restored, but Barr was not (in what may be poetic justice, the Giants won the game 3-1 but Barr did not get the victory). Madlock was fined $500.

By the end of June, Madlock was hitting .311, but already had two more home runs, nine, than he had in all of 1975. He attributed his lower batting average to the 17 games he missed during spring training when the owners locked the players out in a labor dispute.

“The thing that hurt was a lack of spring training,” Madlock said. “Last year after spring training, the players were in shape, and even after an injury, you could get right back in the groove. That’s not the way it has been this season, especially for me.”9

Things turned around after the All-Star break. With the help of a 17-game hitting streak in August, Madlock won his second consecutive batting title with a .339 mark. He also had 174 hits, 15 home runs, 84 RBIs, and a .412 on-base percentage. And he won the title in style. On the last day of the season, he trailed Ken Griffey Sr. of the Cincinnati Reds by .0042 points, .3375 to .3333. Griffey began the Reds’ last game of the season against the Braves on the bench to protect his lead. Madlock went into his last game guns ablazing, going 4-for-4 against the Expos to raise his average to .339. Griffey entered his game when he heard what Madlock was doing, but must have been scared hitless because he went 0-for-2 (striking out both times) and ended up with a .336 mark.

Winning the batting title in that fashion showed that Madlock had a good sense of timing. So did completing his contract just as Major League Baseball was entering the free-agency era. But since this was the Cubs, owner Phil Wrigley was unwilling to open up the coffers and offered Madlock no more than $110,000 for 1977, far below his market value.10 The two sides couldn’t agree on a contract, so Wrigley traded Madlock and infielder Rob Sperring to the San Francisco Giants for outfielder Bobby Murcer, third baseman Steve Ontiveros, and minor-league pitcher Andy Muhistock. In essence it was Madlock for Murcer, and while Murcer had good numbers with the Giants in 1976 (.259, 23 homers, and 90 RBIs), he was almost five years older than Madlock at 31. Anyway, Madlock ended up signing a five-year, $1.3 million contract in San Francisco.

The only batting statistic that went higher for Madlock in 1977 was the number of groundball double plays he hit into, a league-leading 25. He did hit .302 with 12 home runs and 46 RBIs, but these were not the numbers the Giants expected when they traded for him. He attributed the decline in average to playing half his games at Candlestick Park.

“I’m just not going to hit as well at Candlestick Park as I did at Wrigley Field,” he said in a 1978 article. “A lot of balls I hit in the gap get held up by the wind at Candlestick, and you just don’t feel as comfortable batting in cold, windy weather as you do when it’s warm.”11

Madlock’s 1978 season confirmed that assertion, as he hit “only” .309, with 15 home runs and 44 RBIs. Madlock didn’t waste time fighting with opponents that year. He decided to fight with a teammate instead, when he duked it out with pitcher John “The Count” Montefusco during spring training. On March 7 The Count was being interviewed when Madlock interrupted the proceedings. The two started at it before teammates separated the combatants.

Another cornerstone of Madlock’s 1978 season, or keystone in this case, was his switch from third base to second, which allowed Darrell Evans to move from left field to the hot corner. Giants manager Joe Altobelli made the changes to improve team defense; the Giants were 11th in the league with 179 errors in 1977 (only the San Diego Padres made more). In 1978 the Giants had only 146 miscues and their record improved to 89-73 from 75-87.12

Madlock went from the agony to the ecstasy, from the ridiculous to the sublime in 1979. He arrived at spring training angry over an item in Dick Young’s column in The Sporting News that said Giants owner Bob Lurie had accused Madlock of trying to sabotage the team’s effort to sign free agent Rod Carew. Lurie denied making the statement, but Madlock was not mollified.

“Young wouldn’t tell me where he got it from but he said it was 100 percent true,” said Madlock. “He said he got it from a big man in San Francisco so I guess that means somebody in the front office.”13

Madlock said in the same article that he might request a trade after the season, but judging by his play early on, it was a case of the sooner, the better. After 69 games, he was hitting .267, with 7 home runs and 41 RBIs.

Matters came to a head on June 26. Madlock hadn’t been playing much in recent games, and during that time the grandmother who raised him passed away, so even though he was in the lineup that night against the Braves, he was a powder keg waiting to go off. In the sixth, after having avoided a few pitches aimed at his head earlier in the game, he threw an elbow at Braves reliever Bo McLaughlin and the donnybrook was on.

That was the last straw for the Giants, who engineered a six-player trade with the Pirates on June 28 in which they sent Madlock, utilityman Lenny Randle, and pitcher Dave Roberts to Pittsburgh for hurlers Ed Whitson, Fred Breining, and Al Holland.

Much has been said and written about how the 1979 Pirates were a family under the great leadership of National League co-MVP (with Keith Hernandez of the Cardinals) Willie Stargell. However, the Pirates would probably not have even won the East Division, let alone the World Series, without Madlock. Because of his grandmother’s death and a rainout, Madlock didn’t play his first game as a Pirate until July 2. Before that game, Pittsburgh had a 37-34 record and was tied with the Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies for second, 6½ games behind Montreal. The team went 61-30 the rest of the season on the road to the championship. Madlock, now back at third base, hit .328 the rest of the season (.298 overall), with an additional 7 home runs and 44 RBIs, plus .375 in the World Series.

“I think Bill Madlock was the best third baseman offensively and defensively in the major leagues last year,” said Pirates skipper Chuck Tanner in 1980. “It’s hard for a pitcher to go nine innings with a guy like him in our lineup.”14

It’s also hard for Madlock to go nine innings when he is suspended. And that’s what he was after an incident in Montreal on May 1, 1980, when he began arguing a called third strike with home-plate umpire Jerry Crawford. Since Madlock’s was the third out of the inning, a teammate brought him his glove so that he could take his place in the field. Madlock decided to use the glove to emphasize his point, right in Crawford’s face. National League President Chub Feeney suspended Madlock for 15 days and fined him $5,000, but Madlock appealed the suspension. Feeney dawdled on ruling about the appeal, which ticked off the umpires, who threatened to eject Madlock from every game he played. Feeney finally upheld the suspension, which prompted Players Association President Marvin Miller to appeal that decision to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn.

The whole situation was on the verge of exploding into a real mess when Pirates owner John W. Galbreath met with Madlock and his attorney, Steve Greenberg, after which Madlock decided to serve his sentence.15 He withdrew the appeal on June 6. The Pirates went 6-9 while he was gone.

The suspension was a regrettable part of a forgettable season for Madlock that included knee and thumb injuries in addition to the suspension. He hit .277 for the year, the lowest batting average of his major-league career to date, with 10 home runs and 53 RBIs.

Nobody could accuse Madlock of being a prognosticator. As a case in point, he said he didn’t think he would win the batting title in 1981 during a spring-training interview.

“I can’t get the batting title hitting down where I do in the lineup,” he said. “How many people win a batting championship hitting fifth or sixth? Not too many.”16

He nonetheless did win it, even though some luck was involved. Madlock played in only 82 of the team’s 102 games, missing the last two weeks of the strike-shortened season with an injury. He wasn’t even among the top 10 in hits, but his .341 average was the league’s highest in that bizarre season. He also hit 6 home runs, had 45 RBIs, and was an All-Star.

The batting title wasn’t the only good fortune that went Madlock’s way in 1981. After the season he signed a six-year, multimillion-dollar contract, thus avoiding free agency. And he won the Roberto Clemente Award as voted on by the Pittsburgh chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America as the Pirate who most exemplified the standards of excellence set by the Pirates legend.

Madlock got some media flak in 1982 for winning the 1981 batting title as he did, but one would think that a player who had already won two batting titles has earned a bit of slack. He responded to the comments and the pressure of a new contract by having arguably the best season of his career, combining average and power numbers as he never had before. His .319 batting average represented a drop from the previous season, but it was still second in the league behind Al Oliver of the Montreal Expos, who hit .331. He also hit home runs (19) and had a career high in RBIs (95), and his 181 hits were only one below his career high. He was in such a good frame of mind all season that he even defended the umpires after they received a letter from Feeney criticizing their performance.

“The umpiring has been outstanding,” he said. “If I don’t complain, nobody should complain.”17

Once everybody regained consciousness after hearing those comments, the Pirates chose Madlock to replace Willie Stargell as captain for the 1983 season after Pops, retired at the end of the 1982 campaign. Madlock was also named to President Ronald Reagan’s Council on Physical Fitness, which at the time was headed by former NFL coach George Allen.

He responded to the additional responsibility by winning his fourth batting title (.323 average) and playing in his third All-Star game. His power numbers were down from 1982, but still respectable (12 home runs, 68 RBIs). He did have injury problems, including a bout of phlebitis and a torn tendon in his left calf, but still managed to play in 130 games. Yet despite winning the batting title, Madlock wasn’t happy with his season.

“This may have been my worst season,” he said. “I was never able to do what comes natural to me.” 18

Age, injuries, and the loss of natural ability took its toll, because 1983 represented Madlock’s last dominating season in baseball. He had a disastrous year in 1984, hitting only .253 with 4 homers and 44 RBIs, while missing a third of the season after arm surgery. In 1985, he signed a six-year contract at the beginning of July to stay with the Pirates, only to be traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers at the end of August for outfielders R.J. Reynolds and Cecil Espy, plus first baseman Sid Bream. Madlock hit .360 in 34 games as Los Angeles won the NL West Division. In the NLCS, he hit .333 with three home runs but the Dodgers lost the postseason series to the Cardinals, four games to two.

The injury bug followed Madlock to sunny California; he was on the disabled list twice in 1986 and played in only 108 games. The Dodgers released him on May 29, 1987, and the Detroit Tigers signed him as a free agent on June 5. He retired from the major leagues after the 1987 season with a career.305 average, 163 home runs, 860 RBIs, and four batting titles.

Madlock stayed in the game after his major-league career ended. He played in Japan in 1988, batting .263 with 19 home runs and 61 RBIs for the Lotte Orions of the Japan Pacific League. He stopped playing altogether after a 55-game stint in the short-lived Senior Professional Baseball Association in 1989.

Madlock’s post-baseball life has been filled with ups and downs. He had difficulties with the Internal Revenue Service, caused, as it turned out, by his former attorney investing some of his money in sham tax-avoidance schemes. He was also arrested in 1995 for passing bad checks, fined $5,000, and ended up having to pay restitution and performing 200 hours of community service.

He still managed to find work in baseball, as a hitting coach with the Detroit Tigers in 2000-2001, and was named an assistant to the vice president of on-field operations in Commissioner Bud Selig’s office in 2002. He also managed and coached in independent leagues. In 2003 Madlock returned to Keokuk, Iowa, to receive a Distinguished Alumni award from Southeastern Community College.

As of 2015, Madlock lived in Las Vegas, Nevada, and teaches youngsters how to hit at The Dugout batting cage.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author accessed the following:

Baseball-reference.com.

Berkshire Eagle (Pittsfield, Massachusetts).

Biographical Dictionary of American Sports (New York: Greenwood Press).

Chicago Sun-Times.

Daily Herald (Chicago).

Oneonta (New York) Star.

News/Journal (Chicago).

Oneonta (New York) Star.

Sfgate.com.

Southern Illinoisan (Carbondale, Illinois).

State Journal-Register (Springfield, Illinois).

that70scard.com/the-joe-garagiolabazooka-bubble-gum-blowing-contest/.

Notes

1 Steve Wulf, “Glad Times for Mad Dog,” Sports Illustrated, May 9, 1983.

2 Together they had four children, Sarah, Stephen, William, and Jeremy. They later divorced.

3 Brown was inducted into the Baseball Scouts Hall of Fame in 2005 after a career of more than 50 years. Among the players he discovered was Hall of Famer Kirby Puckett.

4 “Beason’s Baseball King ‘Brownie’ Dies,” The Courier (Lincoln, Illinois), January 22, 2009.

5 Wulf.

6 The Washington Senators moved to Texas after the 1971 season.

7 Paul LeBar, “Hrabosky’s Ritual Sparks A Brawl,” Mount Vernon (Illinois) Register-News, September 23, 1974.

8 Kurt Bevacqua of the Milwaukee Brewers blew the field away with an 18¼-inch bubble. People can see the complete contest bracket on card #564 of the 1975 Topps Bubble Gum baseball card series.

9 Joe Mooshil, “Cubs’ Madlock Still Has Hopes for Batting Title,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1976.

10 Joe Rudi, for example, hit .270 with 13 home runs and 94 RBIs and won a Gold Glove with the A’s in 1976, then signed a five-year, $2,090,000 contract with the Angels.

11 Nick Peters, “Madlock’s Bat Picks Up Speed on Road,” The Sporting News, June 24, 1978.

12 They also went from seventh in runs allowed (711) to third (594), which was a factor in their improved record.

13 Associated Press, “Unhappy Madlock Speaks Out,” Santa Cruz (California) Sentinel, March 6, 1979.

14 Mike Tully, “Mad Dog Just Fit Buc Plan,” The Daily News (Huntington, Mount Union, and Saxton, Pennsylvania), March 25, 1980.

15 Steve Greenberg was Hank Greenberg’s son.

16 United Press International, “Madlock Can’t See Bat Title,” April 2, 1981.

17 Associated Press, “Feeney Receives Complaints but Players Say Umps Have Improved,” Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, July 24, 1982.

18 Alan Robinson, “Madlock Wins Fourth Batting Title,” United Press International, October 4, 1983.

Full Name

Bill Madlock

Born

January 12, 1951 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.