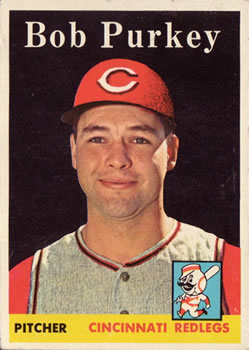

Bob Purkey

Right-hander Bob Purkey learned the knuckleball from Branch Rickey and fashioned a 13-year big-league career with a smorgasbord of pitches plus excellent control.

Right-hander Bob Purkey learned the knuckleball from Branch Rickey and fashioned a 13-year big-league career with a smorgasbord of pitches plus excellent control.

Robert Thomas Purkey was born in Pittsburgh on July 14, 1929. His father, Edward, was an insurance agent and his mother, Anna, a homemaker. The Purkeys had two other sons, Edward and Donald. Bob excelled at South Hills High School and signed with the hometown Pirates after graduation.

Starting his career at Greenville in the Class D Alabama State League in 1948, Purkey was an immediate star. He pitched a no-hitter on his way to a 19-8 record and a 3.01 ERA. The next year he moved up to Class B with Davenport in the Three-I League and contributed 17 victories. At the age of 20 he was promoted to the fast Double-A Southern Association and managed a 12-12 mark for fifth-place New Orleans. Since the parent Pirates had finished last in 1950, Purkey and his teammate Vernon Law had a good shot at the majors.

While Law made the big-league team in 1951, Purkey made the US Army team. He was drafted and assigned to Fort McNair in Washington, D.C.

Purkey had met Joan Latsko, a sister of a sandlot teammate, while he was in high school, but she refused to go out with him. When he came home in the offseason from minor-league ball, they ran into each other at a bowling alley. Bob didn’t call her, so Joan took action. She invited him to go on a hayride, and he accepted. Except there was no hayride—she had made it up. She called back to tell him it had been canceled and, as she had hoped (or schemed), Bob suggested they make other plans.[1] They were married on June 21, 1952, while he was on leave from the Army, and stayed together for 55 years while raising son Bobby and daughter Candace.

Military service took two years from Purkey’s professional career, but he pitched for an Army team that won the 1952 National Baseball Congress (semipro) championship. The team fielded several other professional players, including his Pirates teammate Danny O’Connell and the Braves’ bonus pitcher Johnny Antonelli. The soldier-ballplayers traveled to Japan to play that nation’s champions as part of the American diplomatic effort to cultivate friendly relations with the World War II enemy.

Discharged in the spring of 1953, Purkey spent another season in New Orleans (11-13, 3.41), earning a promotion to Pittsburgh in 1954. The Pirates were headed for their third straight 100-loss season. Purkey did his part with a 5.07 ERA and a 3-8 record while starting and relieving. He opened the ’55 season in the starting rotation and pitched strongly in three of his first four outings, including six perfect innings against the Dodgers. Then he came down with a sore shoulder. Trying to pitch through it, he lost six straight, was sent to the bullpen, and finally demoted to New Orleans in June. General manager Branch Rickey sent him down to work on a new pitch: “Mr. Rickey took me aside for ten pitches and taught me how to throw a knuckleball.”[2] His shoulder recovered, but a knee injury kept him in the minors in 1956 with Triple-A Hollywood.

The Pirates had moved up to seventh place in 1956, losing 88 games—their best record in seven years. Rickey was gone, but his strategy of stockpiling young players was paying off. Roberto Clemente, Dick Groat, and Bill Mazeroski were in the lineup, and Vernon Law, Bob Friend, and Ronnie Kline gave them three young starters, with Elroy Face anchoring the bullpen. Purkey was the favorite for the fourth starting spot in 1957, if his knee held up.

It did. By mid-June he was leading the league with a 2.20 ERA. The Pittsburgh Press’s Les Biederman wrote that the right-hander “has been the most valuable Pirate.”[3] Purkey won his tenth game on July 27, but his breakthrough season turned sour. He lost six straight and finished 11-14 with a 3.86 ERA. The Pirates lost 92 and again occupied seventh place.

In December Pittsburgh swapped Purkey to Cincinnati for an undistinguished left-hander, Don Gross. Purkey welcomed the trade: “As much as I like to play in my hometown, I also like to have some runs scored for me.”[4] He had read a news story naming Friend, Law, and Kline as the Pirates’ key starters for 1958, a sign that the club didn’t think much of him. “Cincinnati had a team that scored a lot of runs but didn’t have much pitching, so it was a good deal for me to go there,” he recalled.[5] Gross won only six games for the Pirates, while Purkey became a mainstay of the Cincinnati rotation. For years afterward Pittsburgh general manager Joe L. Brown regretted the deal as “the worst trade I ever made.”[6]

The Redlegs, as they were called during the anti-communist frenzy of the 1950s, had finished fourth in 1957 but recorded the league’s worst ERA. General manager Gabe Paul reshaped his pitching staff, adding Purkey and Harvey Haddix in the offseason and former Cy Young Award winner Don Newcombe in June 1958. Unfortunately for the pitchers, he gave up a big portion of the team’s power. Cincinnati finished fourth again, costing manager Birdie Tebbetts his job. Purkey emerged as the staff ace with a 17-11 record and a 3.60 ERA. At 28 he had come into his own.

By July Purkey had won eight games. The National League’s All-Star Game manager, the Braves’ Fred Haney (Purkey’s former Pittsburgh skipper), chose him for the team, although three other Cincinnati pitchers had lower ERAs. He did not appear in the game. He was a particular bane of the Giants, the Reds’ rivals for third place, holding them scoreless for 46 consecutive innings over four seasons. On September 14, 1958, the Giants accused him of throwing at Willie Mays and Leon Wagner. After Mays reached base and stole second, he and Purkey began jawing at each other. Purkey came off the mound and started for Mays, but an umpire stepped between them.

Purkey resisted being typecast as a knuckleball pitcher. He threw a slider, changeup, slow curve, sinker, and moving fastball. “I wouldn’t trade my fastball for a lot of others in this league that are thrown faster but straighter,” Purkey said. “My fastball moves ‘in’ to a right-handed batter.” He said it moved six inches, but some hitters thought it was even more. “I don’t depend mainly on any one pitch. My knuckler isn’t as good as Hoyt Wilhelm’s, my fastball not so overpowering as Ryne Duren’s, my curve not so sharp as Vernon Law’s. But put them all together and they give me a pretty fair repertoire…. If I’m right I can set up any batter with almost any type of pitch.” The variety of pitches frustrated hitters. The Dodgers’ Ron Fairly said, “He used to throw everything but the kitchen sink. Now he throws the sink, too.”[7]

The flamboyant Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince claimed Purkey could put his knuckler wherever he wanted to, but the pitcher disagreed: “If you throw a good knuckleball you have no idea what it’s going to do. I just tried to throw it down the middle. I was basically a sinkerball, slider pitcher. I didn’t have a great fastball, but I had pretty good location and that’s the most important thing. I started to throw the knuckleball because I needed a strikeout pitch for the big swingers.”[8] A big man at 6-feet-2 and about 180 pounds, he was never overpowering; his best pitch was a strike, followed by another one. He walked only 2.2 batters per nine innings in his career. Reds pitching coach Tom Ferrick commented, “You watch Purkey warm up, and you wouldn’t give a nickel for his chances of beating anyone. He’s not the overpowering type of pitcher who catches your eye. Instead he’s a cutey. His pitches are up and down, in and out. He keeps the batters off stride. Some guys impress you because they throw hard. Purkey, though, impresses you because he gets the hitter out.”[9]

As Cincinnati dropped to fifth place in 1959 and sixth in 1960, Purkey’s marks were 13-18 and 17-11. Despite the presence of young stars Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson, the Reds were an aging club going downhill until Bill DeWitt took over as general manager in November 1960 and blew up the roster. As Bill James pointed out, “DeWitt, in sum, simply kept everyone who hit better than .265 and had an ERA under 4.00, and got rid of everybody who didn’t.”[10] The key acquisitions were pitcher Joey Jay, who won 21 games, and third baseman Gene Freese, who hit 26 homers. Young left-hander Jim O’Toole, first baseman Gordy Coleman, and center fielder Pinson blossomed, Robinson won the MVP award, and the underdog Reds—who had finished 28 games behind in 1960—won 93 to claim the 1961 pennant. Purkey finished 16-12 with a 3.73 ERA

After Cincinnati and the Yankees split the first two games of the World Series, Purkey started Game Three at home in Crosley Field. He held New York hitless for the first four innings and shut them out through six. “Purkey was pitching as if he could go on forever, mixing sliders and flutterballs with fastballs so effectively the Yanks were slamming their bats into the dugout in disgust,” sportswriter Herb Kamm wrote.[11]

In the eighth Yankee pinch-hitter John Blanchard homered to tie the score at 2-2. Roger Maris led off the top of the ninth, six days after his historic 61st home run. Maris was 0-for-10 in the Series. The Reds’ scouting report recommended pitching him up and in, but Purkey had set him down three times with “slop sliders” low and away. This time he threw a hard slider and Maris hammered it far into the right-field seats to win the game for New York. “That pitch wasn’t too bad,” Purkey mused as he shaved in the clubhouse after the game. “Maybe I shoulda tried to get into him like they said.” He paused, with his razor hovering over his throat. “Maybe, that is.”[12]

It was the turning point of the Series. The Yankees never trailed again and beat the Reds decisively in Games Four and Five.

Purkey’s career peaked in 1962. He won his first seven decisions, was named National League Player of the Month in May, and was 14-2 at the season’s midpoint. But Cincinnati fell behind the Giants and Dodgers to finish third, although they won five more games than in their pennant year. (The schedule had been expanded to 162 games when the league added two new teams.) Relying more heavily on his knuckler, Purkey posted the league’s third-best ERA, 2.81, with a 23-5 record. But he got only one vote for the Cy Young Award as the Dodgers’ Don Drysdale won 25 and led the league in strikeouts to earn the honor. Purkey’s reward was a raise to around $40,000, said to be the highest salary ever for a Reds pitcher.

After winning 86 games and making three All-Star teams in five years, Purkey hit a wall in 1963. At age 33 he hurt his arm in one of the first workouts of spring training: “I got sharp pains in my lower right shoulder, and I couldn’t get any snap in my wrist,” He said.[13] He said it was the same injury as in 1955, when he had to go back to the minors. He didn’t pitch until May 7 and never rounded into form, as he was unable to regain command of his knuckleball and lost movement on his fastball. After his record fell to 1-4 in June, he studied home movies that his roommate, Joey Jay, had filmed during his successful 1962 season. He discovered that he had shortened his arm motion and wasn’t getting full extension when he threw the fastball. He pitched effectively in his next two starts, one of them a shutout on 76 pitches.[14] But he finished 6-10 and completed only four of 21 starts.

As the 1964 season began Purkey said his arm was fine, but his results were inconsistent. In May he and manager Fred Hutchinson broke out Jay’s home movies again, and he followed up with two strong complete games. He struggled along at 3-6 until July, when he went to the bullpen for three weeks. Restored to the rotation, he won five straight to finish with an 11-9 record and 3.04 ERA. It was his last season as an effective pitcher. In December the Reds traded him to St. Louis for veteran pitcher Roger Craig and outfielder Charlie James. Still fighting a sore arm, Purkey put up a 5.79 ERA for the Cardinals in 1965, though his record was 10-9, and they sold him to Pittsburgh before the 1966 season. When the Pirates released him in August, he said, “I have no regrets and I leave with good feelings all around. I’ve taken a great deal out of baseball and I only hope I have given something in return.”[15] His big-league career ended at age 37 with a 129-115 record and an adjusted ERA of 104, slightly better than average.

Purkey had prepared for life after baseball. Following in his father’s footsteps, he began selling insurance for teammate Bob Friend’s agency in the 1950s. Now he opened his own business, the Bob Purkey Insurance Agency, in the Pittsburgh suburb of Bethel Park. He ran the firm for more than 30 years while enjoying his family, golf, fishing, and hunting. A friendly, outgoing man, “Purk” was a natural salesman. He said his fame got his foot in the door, but he had to prove he knew his stuff to close the deal.

He did some broadcasting for the Pirates and was active in the team’s alumni association. He returned to Cincinnati for old-timers games; the Reds inducted him into their Hall of Fame in 1974. “If I could still run and still throw, I’d suit up and play tomorrow,” he said. “I loved the challenge of pitching.”[16]

Purkey’s son and namesake pitched for Gulf Coast Community College in Panama City, Florida. While the team was in Colorado for a tournament in 1973, 18-year-old Bobby collapsed while swimming and died of an undiagnosed heart ailment. His death devastated the family. The Bethel Park High School baseball field was named for him.

After their daughter Candy married, Purkey and his wife reveled in the role of grandparents to her two children. “When you’re raising your own kids, you’re trying so hard to make them perfect,” Bob said. “But when you’re a grandparent, they come perfect.” When Joan began having health problems, he sold his business in 1998 and retired, but told the company to keep a desk open for him, just in case.

He suffered from Alzheimer’s disease in the last few years of his life and died at 78 on March 16, 2008. Joan had passed away just a month earlier. In a eulogy his son-in-law, Bob Holland, said, “Purk had friends in high places, that’s true, but it’s not the whole story. Purk had friends in all places, and he treated them all the same, with dignity, respect, and love.”

[1] Personal information about Purkey and his family comes from e-mail exchanges with his daughter, Candace Holland, in 2010.

[13] “Cincinnati Reds: The Pennant Is Up to the Doctors,” Sports Illustrated, April 8, 1963, online archive.

Full Name

Robert Thomas Purkey

Born

July 14, 1929 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

Died

March 16, 2008 at Allegheny County, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.