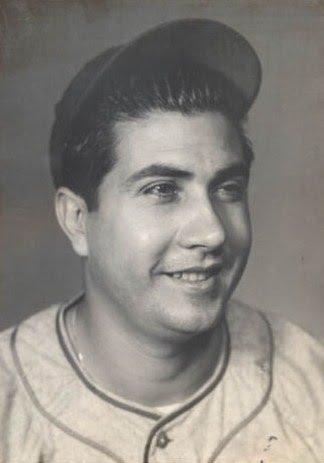

Rogelio Martinez

This slender sidearm righty appeared in just two big-league games, in 1950. Nonetheless his career is more significant than it appears. “Limonar” – so called for the country town where he learned to play ball – was one of the icons of Cuban amateur baseball in its most glorious, romantic, and competitive era, the early 1940s.

This slender sidearm righty appeared in just two big-league games, in 1950. Nonetheless his career is more significant than it appears. “Limonar” – so called for the country town where he learned to play ball – was one of the icons of Cuban amateur baseball in its most glorious, romantic, and competitive era, the early 1940s.

Author Roberto González Echevarría highlighted four pitchers – “revered amateurs and later professionals” – who made it to the majors.1 The most prominent was Conrado Marrero, who died in 2014, almost four years after Martínez – they were among the last living links to that time. Julio “Jiquí” Moreno, a dazzling flamethrower in his youth, was a distinguished runner-up. Sandalio “Potrerillo” Consuegra had the most success in the US, where he was known as Sandy. These three men and Martínez all started in the big leagues with the 1950 Washington Senators.

Rogelio Bautista Martínez Ulloa was born on November 5, 1918, in the town of Cidra. Located about 55 miles southeast of Havana in Matanzas province, Cidra was also the birthplace of Hall of Famer Martín Dihigo. Rogelio was the 14th of 15 children born to Antonino Martínez and Carmela Ulloa. The area was predominantly agricultural (sugarcane was the main crop), and it’s little surprise that this was Antonino’s work.

Rogelio played baseball from the age of seven. Limonar was the name of the initial team that he played with, and the fans gave him that as a nickname since the word was embroidered on the back of his uniform shirt. The town, roughly 10 miles east of Cidra, gave another great ballplayer to the world: shortstop Silvio García.

Roberto González Echevarría wrote, “A significant development in the thirties and forties was the emergence of players, mostly pitchers, from the provinces. . .white guajiros – country bumpkins.” He added that “the rural aristocracy of the Amateur League . . . fed on the nationalism of the period.”2

Even though white-only social clubs dominated that scene, the level of competition was high. An expert on Cuban baseball, Peter Bjarkman, described it as “a thriving tradition that grew up alongside Havana’s pro league and that, for much of the first half of the twentieth century, actually outstripped the pro game in island-wide popularity and fan stature.”3 Cuban all-star teams of the day also made a good showing against major leaguers. After the Boston Red Sox lost such a game in 1941, manager Joe Cronin reportedly said, “They may be amateurs, but many are better than our players.”4

In 1940 Martínez joined Deportivo Matanzas in the Amateur League. He remained there through 1944 or possibly 1945, posting a record of 49-22 and a 2.62 ERA. The 1943 season was noteworthy; at least one other expert, César López, viewed it as the best-quality season for the Cuban amateur league. It was a great race between Círculo de Artesanos, starring Jiquí Moreno, and Deportivo Matanzas. Amateur league games took place just once a week, and Moreno started virtually every Sunday for Artesanos. By contrast, Matanzas relied on three pitchers: Martínez, Consuegra, and Ángel “Catayo” González. The trio was known, without much imagination, as Los Tres Mosqueteros – The Three Musketeers.5

Given the schedule, one wonders how they stayed sharp, but manager Pipo de la Noval did not use them in rotation – rather, he gave them each three innings a game.6 González Echevarría called them “the best staff ever in Cuban amateur baseball.”7 He added, “All three were also feared batters.”8

Heading into the season’s final week, Matanzas had a record of 22 wins, 5 losses, and one tie. Artesanos was half a game back at 22-6. Jiquí Moreno struck out 14 (including eight in a row) to put his team ahead in the win column, but Matanzas responded with a victory of their own to take the title.

Martínez also starred in international competition for Cuba. He posted a 5-1 record in three Amateur World Series: 1941, 1943, and 1944. He was especially sharp in the 1943 edition (3-0, 0.96). A signature outing came when he shut out Mexico on just 63 pitches.

In June 2010, 92-year-old Andrés Fleitas – who handled Martínez with the national team in 1943 – described his batterymate. “Excellent control, he threw hard, and his delivery was from the side, so he was very difficult for right-handed batters.”9

The amateur stars were popular heroes in Cuba. As González Echevarría wrote, Marrero, Moreno, Consuegra, and Martínez “often appeared in magazines, sometimes even on the covers.”10 In the prevailing fashion, like many Hollywood stars, they sported pencil mustaches.

Rogelio was a loyal friend. When the Amateur League suspended Marrero in 1942 for a rules violation, Martínez was the first to declare that he would be very pleased to see El Premier pardoned.11

On December 20, 1943, Martínez married Olga I. Alonso, an elementary-school teacher whom he had met when she attended one of the games he was pitching. As Conrado Marrero remembered in 2010, her father owned a hotel in Matanzas. The duration of their marriage was remarkable: nearly 64 years. They had two daughters, Ileana and Olga. Limonar’s family was his greatest pride.

After Deportivo Matanzas won another amateur championship in 1945, Martínez turned pro. He played for the Saltillo franchise in Mexico’s short-lived and overshadowed Liga Nacional. This league operated from 1944 through 1946 and again in 1950; it joined Organized Baseball for part of the ’46 season. As historian Tito Rondón noted, though, “[Mexican baseball magnate] Jorge Pasquel leaned on the media to make them ignore the ‘other league.’”12

In the winter of 1945-46, Limonar played in Cuba’s professional winter league for the first time. With the Almendares Alacranes (Scorpions), he was 1-1 in 13 games. He returned to Saltillo for the following summer. Conrado Marrero (who had run afoul of Cuba’s Amateur Athletic Union again) had also come to the Liga Nacional. When he arrived in Mexico City along with his traveling companion Héctor Rodríguez, he found that Martínez and Olga were there in the same hotel, along with several other Cuban ballplayers.

Rogelio’s daughter Ileana recalls hearing that he won 25 games in Saltillo in 1945 and 20 more in 1946. Unfortunately, the league’s statistics are very scarce, and confirmation is still pending, but Conrado Marrero recalled that Limonar made the Southern Division’s All-Star team in 1946 for the Liga Nacional. Marrero, who was a big winner for the Indios of Ciudad Juárez, represented the Northern division.

The winter of 1946-47 saw Martínez pitching for the Matanzas club in La Liga de la Federación. This league sprang up after entrepreneurs Bobby Maduro and Miguelito Suárez built Havana’s new Gran Stadium. In response, Julio Blanco Herrera – the proprietor of the Cuban Winter League’s old ballpark, La Tropical – started a rival circuit. The Federation was in good standing with Organized Baseball, whereas the Cuban Winter League was using “outlaw” players who had jumped to Mexico in 1946. Attendance was poor and losses were heavy, however; the Federation folded as of year-end 1946. Martínez went 2-3 in six games.

For the summer of 1947, Rogelio joined the Havana Cubans, a franchise born the previous year. The Cubans, who played in the Florida International League, were a farm team associated with the Washington Senators. The principal shareholders were Senators owner Clark Griffith; Merito Acosta, a Cuban who had played for Washington back in 1913-18; and scout Joe Cambria, who operated in Cuba and signed numerous men from that country for Griffith over the years. The team moved from La Tropical to Gran Stadium.

That May, the Brooklyn Dodgers exercised a $20,000 option to claim three players from the Cubans, including Martínez. The Miami News wrote, “However, it is understood the Dodgers will leave the players in Havana until a farm team puts in a request for their services.”13 Later that month, United Press reported that the three men were suspended for refusing to report to Triple-A Montreal.14 Though supposedly they decided to go, they never did. In fact, Havana had to refund the $20,000.15

Martínez pitched well for Havana (9-4, 1.90), but to some degree the team’s business practices overshadowed his performance. Havana had listed him as a rookie, but George Trautman, president of the minor leagues, determined that he should have been classified as a “limited service player.” As a result, Florida International League President Wayne Allen removed three games from their win column and fined the club $150. Previously, the Cubans had also been fined $500 for alleged overpayments to Martínez.16

Cuba had a new league in the winter of 1947-48: La Liga Nacional, or Players’ Federation League. Limonar started with Santiago, but after that club disbanded on December 15, he went to Alacranes. His overall record was 2-6, 3.03. The league completed the season but was defunct thereafter.

Martínez did not play in the US in 1948. In all probability, it was because he had played alongside “outlaws” such as Sal Maglie and Max Lanier in La Liga Nacional. He returned to Mexico, going 12-7, 3.14 with Puebla. That winter was his most effective overall in the Cuban league: 4-1, 2.85 with Marianao.

Limonar rejoined the Havana Cubans in the summer of 1949. Rogelio had a fine year (19-9, 1.86), ranking second on the staff in wins behind Conrado Marrero’s 25. His winter season in Marianao was just fair overall (5-5, 3.66) – but it featured a career highlight. On February 15, 1950, against Almendares, Martínez pitched the seventh no-hitter in Cuban League history.17 Andrés Fleitas remembered, “I was the last batter in that encounter and I lined out to second base. All the Marianao players came running out to salute Limonar.”18

Rogelio continued to pitch well for Havana in 1950 (10-4, 1.72). In July, the Senators summoned him and sent down 21-year-old pitcher Bob Ross. The Associated Press reported that outfielder Roberto Ortiz sighed because now there were three countrymen for whom he had to translate with manager Bucky Harris: Marrero (who understood more English than he let on), Consuegra (who had come on board in early June), and Limonar. 19

The 31-year-old “rookie” arrived in Washington on July 11. Consuegra echoed Limonar’s feelings when he said, through Ortiz, “I know he can help Senators. He better pitcher than me and I already win three games in American League.” There were two other items of note: Martínez said that he was just 28 years old, and his height was given as 5-feet-10. 20 His family confirmed that he stood 6 feet tall, though, as listed in baseball references.

Two days later Limonar made his major-league debut at Griffith Stadium against the Detroit Tigers. He retired the last two batters of the game in a 5-2 loss. His only other appearance came on July 16, when he started the second game of a doubleheader against St. Louis. The Browns knocked him out of the box in the first inning, scoring four runs, and Martínez took the loss.

Three days before Washington called Rogelio up, he had hurt his knee, and he didn’t tell the club.21 It definitely affected him on the mound; he also had trouble running and covering bases. In 2010, Conrado Marrero recalled that he said, “Limonar, why are you coming here in this condition?” Martínez told him that Joe Cambria had insisted strongly and that he gave in to the demands.

The truth came out in the press; a week after his lone start, the Senators sent Martínez down and called up Julio Moreno (though Jiquí would not actually make it to Washington until August).22 Yet another Cuban hurler would join the club from Havana before the season was over: Carlos “Patato” Pascual, older brother of Camilo Pascual.

Most likely because of his knee, Limonar pitched mainly in relief for Marianao that winter. In 44 innings across 25 games, he was 1-1, 4.26. He did not play in the US in 1951. Instead, he went to the Dominican Republic, where the league played in the summer from 1951 through 1954. Cuban baseball historian Ángel Torres said that he posted a 4-1 record with Estrellas Orientales.23

The Torres story also notes that Martínez pitched in Venezuela for the club Pastora de Occidente, again going 4-1, ostensibly in 1951. This team was in the nation’s Western League (Liga Occidental), whose records in those years do not appear in the Venezuelan baseball reference books.

Marianao waived Martínez before the 1951-52 winter season, perhaps because he was hurting again. The Havana Rojos picked him up, and he got no decisions in very limited action (six innings in five games). The Reds, under Miguel Ángel “Mike” González, won their second of three straight Cuban championships. Martínez was on the roster for the fourth Caribbean Series, and in his only appearance, he got a win in relief against Panama as Cuba scored three runs in the bottom of the eighth inning.

Limonar made a comeback in 1952, posting a career high in wins for another FIL team. The Tampa Smokers offered him a better contract than Havana, and he rewarded them by going 20-12, with a 1.91 ERA.

Limonar’s Cuban winter action concluded in 1952-53 as he went 1-1 in 19 innings across 11 games for Havana. His career totals in the pro leagues at home were 16-18, 3.09. Martínez made one more brief and uneventful Caribbean Series appearance in February 1953.

One of Rogelio’s sons-in-law, Joe Fernández, heard that at some point Martínez appeared in Colombian winter ball too. Information on this league is largely limited to brief reports in The Sporting News, and it has not been possible to determine when this episode may have taken place.

Martínez was back in the States in 1953, but the season was a comedown for him. He was just 1-7 with a 7.69 ERA for Tampa and spent the bulk of the summer in Carolina League with the Shelby Clippers of the Tar Heel League. Against this lower-level competition, he was 12-10, 3.51.

In 1954, after four games for Tampa, the 35-year-old returned once more to Mexico. He had a respectable year with the Mexico City Blues (13-9, 4.19). The pro career of Limonar Martínez ended in 1955 with eight games for the Mexico City Tigres (2-4, 4.14).

After leaving baseball, Martínez worked in a textile factory in Cuba. He left his homeland in 1962, three years after Fidel Castro took power. According to his family, that year he was offered the opportunity to be a coach and a relief pitcher in Texas with a minor-league team in the organization of the Houston Colt .45s, today known as the Houston Astros. He did not accept because he believed that he could not perform at the high standards he was used to in the past. Joe Fernández added, “He got a number of calls about becoming a coach over the years, but he turned them all down. He was really a proud and shy man. He wasn’t like Tommy Lasorda that way.”

Instead, Rogelio and his family settled in New York City, living in Astoria and Jackson Heights, Queens. For many years he continued to work in the textile business in various companies as a mechanic. He retired in 1987.

Limonar remained a fan of baseball and in particular of the New York Yankees, who were big favorites for generations of Cubans. He enjoyed watching games with his son-in-law Joe and grandson Michael, who were the other fans in the family. In particular, he could look at pitchers and tell early when they didn’t have it.

Martínez participated in several Juegos de Recuerdo (Cuban old-timers’ games) at New Jersey’s Roosevelt Stadium. Some of the participants were Tony Oliva, Tony Taylor, Sandy Amorós, and Beto Ávila. Joe Fernández said, “He didn’t want to go down to the games in Miami. He would want to work out beforehand too because he didn’t want to look bad.”

In 2005, Martínez and his wife, Olga, moved in with his daughter Olga and her family, who lived in Waterford, Connecticut. In June 2007, Olga Alonso Martínez passed away. The death of his wife had a great impact on Rogelio’s emotional well-being, and his physical health deteriorated too.

On May 24, 2010, Rogelio Martínez passed away at the age of 91. He had suffered an internal hemorrhage after a fall – which, by bizarre fate, was prompted by his same old knee injury. 24 In addition to his two daughters and their husbands, five grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren survived him.

In June 2010 Conrado Marrero looked back nearly 70 years to recap his memories of Limonar Martínez. “A pitcher with very good control,” he said, “who was a very decent and serious man.”

An updated versin of this biography appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Joe and Ileana Fernández, and to Jesús Rubio for the introduction. Continued thanks to Rogelio Marrero for obtaining Conrado Marrero’s input.

Sources

Mexican baseball historian Jesús Alberto Rubio published two of several online obituaries of Limonar Martínez. The others are footnoted below, but the Rubio articles benefit from his Mexican sources and from Joe and Ileana Fernández’s input.

http://www.reydelosdeportes.com/DetalleColumna.aspx?IDarticulo=2604

http://www.conexioncubana.net/blogs/remehibe/limonar-martinez/

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted:

Figueredo, Jorge S., Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2003).

Figueredo, Jorge S., Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Press, 2003).

Treto Cisneros, Pedro, Editor, Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano (Mexico City, Mexico: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 1998).

Notes

1 Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 220.

2 Ibid., loc. cit.

3 Peter C. Bjarkman, Diamonds Around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2005), 6.

4 Bob Rubin, “Cuba relives big-league baseball ties,” Miami Herald, March 28, 1999.

5 Marino Martínez Peraza, “Un mosquetero del Deportivo Matanzas.” El Nuevo Herald, May 29, 2010.

6 Jorge Alfonso, “Amplitud del Horizonte (II).” Béisbol Cubano website (http://www.cubasi.cu/beisbolcubano/historia/amplitud-del-horizonte-II.htm), April 9, 2007.

7 González Echevarría, op. cit., 232.

8 Ibid., 246.

9 Jesús Saiz de la Mora, “‘Limonar’ Martínez: grande entre los grandes.” Libre Online website (http://www.libreonline.com/home/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=10640:limonar-martinez-grande-entre-los-grandes&catid=17&Itemid=68), June 2, 2010.

10 Ibid., 220.

11 Ricardo G. Menocal, “Pro-Marrero.” April 14, 1943. Clipping from Rogelio Marrero files.

12 Tito Rondón, “The League That Disappeared.” La Prensa del Beisbol Latino, Bulletin of SABR’s Latin American Committee, Autumn 2009: 7, 8.

13 “Dodgers Purchase Three From Cubans,” Miami News, May 4, 1947: 2-C.

14 United Press, “Cubans Join Royals,” May 22, 1947.

15 “Del Calvo takes Hill For Saints,” St. Petersburg Independent, July 2, 1947: 7.

16 Associated Press, “Havana Penalized For Second Time In One Week,” August 23, 1947.

17 Sources vary as to when this event took place. Figueredo cites February 15; Bjarkman and Martínez Peraza cite February 6.

18 Saiz de la Mora, op. cit.

19 Associated Press, “Senators Import Another Cuban, Pitcher Martínez,” July 12, 1950.

20 “Senators Happy As Third Cuban Goes To Work.” Expanded version of story cited in Note 17.

21 Martínez Peraza, op. cit.

22 Associated Press, “Senators Buy Julio Moreno,” July 23, 1950.

23 Torres, Ángel. “Sentido fallecimiento del lanzador cubano Limonar Martínez.” Diario las Américas website (http://www.diariolasamericas.com/news.php?nid=100420), May 28, 2010.

24 Martínez Peraza, op. cit.

Full Name

Rogelio Bautista Martinez Ulloa

Born

November 5, 1918 at Cidra, (Cuba)

Died

May 24, 2010 at New London, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.