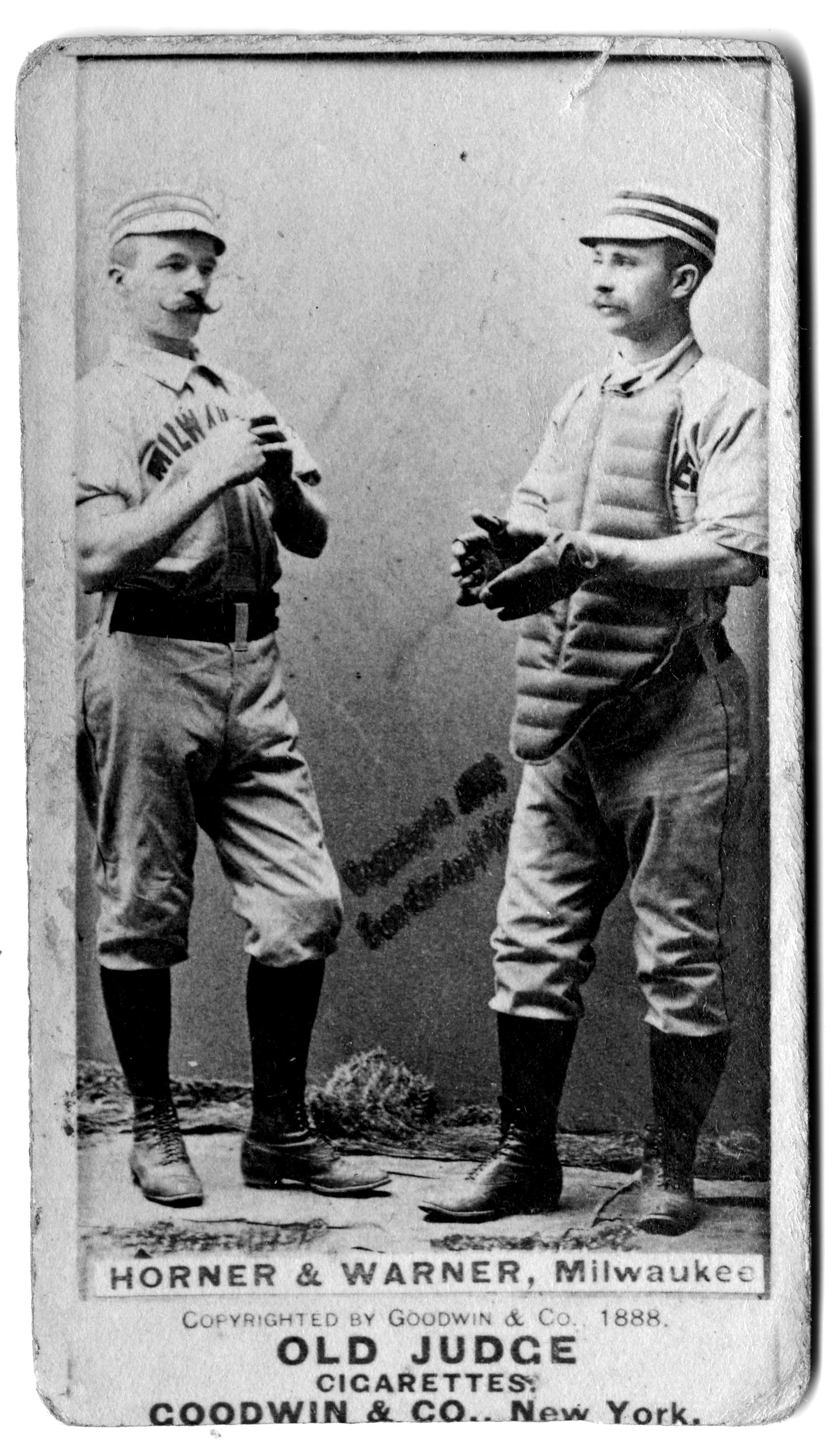

Jack Horner

“Horner and Warner are a strong team… [Pitcher] Horner’s delivery is very quick, he controls good curves and he is a magnificent fielder… Warner, as catcher, is likewise good. He is as agile as a cat and throws with a precision that is not often seen.” — Fort Wayne (Indiana) Gazette, April 6, 1884

“Utica and Toronto both offered a good round sum for Horner, but had no place for Warner, and the electric pitcher could not be tempted into signing without his catcher who has supported him so long and so cleverly. In fact, the success of one depends on the other—each forming a part of a harmoniously working machine.” — Buffalo Truth, January 2, 1887

In the 1970s, Steve Carlton preferred to pitch to his “personal catcher,” Tim McCarver. In the 1920s, catcher Hank DeBerry was Dazzy Vance’s favorite target.1 And in the first decade of the 20th century, Lou Criger caught Cy Young and Osee Schrecongost caught Rube Waddell.

In the 1970s, Steve Carlton preferred to pitch to his “personal catcher,” Tim McCarver. In the 1920s, catcher Hank DeBerry was Dazzy Vance’s favorite target.1 And in the first decade of the 20th century, Lou Criger caught Cy Young and Osee Schrecongost caught Rube Waddell.

The pairing of pitchers and catchers was common in the 1880s,2 but the collaboration of pitcher Jack Horner and catcher Ed Warner was uncommon. After teaming on Baltimore sandlots as teenagers, they toured the minor leagues together from 1884 to 1889. Dubbed “the Baltimore battery,” the duo played for teams in Indiana, Ohio, Virginia, New Jersey, Ontario, New York, Wisconsin, and Connecticut.

William Frank “Jack” Horner was born in Baltimore on September 21, 1863. He was the eldest child and only boy among the seven children of Robert and Anastasia Horner. In the early 1880s, Jack was “the most prominent of the amateur twirlers” in Baltimore.3 He organized and pitched for a team known as “Our Boys,” and Warner was his catcher. He and Warner were the same age. The youthful pair left Baltimore in the spring of 1884 to play for the Fort Wayne, Indiana, team of the Northwestern League.

Horner was a right-hander, 5-feet-10½ and 155 pounds.4 He and Warner did not set the world on fire at Fort Wayne. Horner’s won-lost record was 4-15, albeit with a fine 1.90 ERA. He batted .182 and Warner hit .179. The team disbanded in August, and the battery mates moved on to Ironton in the Ohio State League. After the Ironton team disbanded in September, they headed east to Norfolk, Virginia, where they were sensational.

On September 30, 1884, Horner and Warner played for a Norfolk squad in an exhibition game against the Toledo team of the American Association, then a major league. Pitching for Toledo was Hank O’Day, who would later gain fame as an umpire. The game was a nine-inning scoreless tie. O’Day allowed three hits, and Horner allowed only one.5

If anyone thought that was a fluke, Horner and Warner proved otherwise ten days later. Against Columbus, the second-place team of the American Association, Horner threw a three-hit shutout in a 5-0 Norfolk victory. What’s more, he struck out 13. Warner contributed two of Norfolk’s seven hits off Columbus pitcher Al Bauer.6

In two more games against Toledo, Horner won one and lost one.7 And on October 22, he allowed three hits and fanned 10 but was edged, 5-4, by the Baltimore Orioles, another American Association team.8 Sporting Life called Horner a “phenomenal young pitcher.”9

The Horner-Warner show made two stops in 1885, at Trenton, New Jersey, and Toronto. And in the spring of 1886, they went to Upstate New York to play for the Rochester Maroons of the International League.

On June 5, 1886, Horner hurled a three-hit shutout in Rochester’s 9-0 romp over Oswego, New York.10 He followed that with a four-hitter against Hamilton, Ontario, on June 9, a three-hitter against Oswego on June 28, and a four-hitter against Buffalo on July 2.11 Horner “has the excellent support of Warner, his clever catcher,” noted Sporting Life.12 However, on September 1, Horner alone was acquired by Oswego,13 and the battery mates were temporarily separated. In the offseason, Horner refused offers from several teams until he found one—Hamilton—that would sign both him and Warner for the 1887 season.

A doubleheader was played at Hamilton on June 21, 1887, to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, the 50th anniversary of her accession to the throne. In the first game of the twin bill, Horner dueled Toronto’s Ed “Cannonball” Crane and came out on top, 1-0.14 In a rematch nine days later, Horner beat Crane, 7-1.15

Warner caught other Hamilton pitchers besides Horner, though Horner pitched only to Warner. Horner demonstrated his versatility by playing in the outfield, or at second base or shortstop, when not pitching. According to Sporting Life, he was an excellent infielder and an energetic player who put his heart and soul into every game.16

Horner pitched a four-hit shutout at Newark on August 17. But all was not rosy. In consecutive starts a week later, he was battered in Buffalo, losing 13-6 and 14-3.17 At season end, he had a 15-12 record.18 He hit .304 and Warner batted .241. It was a hitters’ league with a .324 league average.19

In November it was reported that “Horner and Warner want $250 a month each from Hamilton” to return for the 1888 season, and “one will not sign without the other.”20 They didn’t get it from Hamilton but did get it from Milwaukee of the Western Association, and so the Brew City was the next stop on their tour.

The Milwaukee team had several up-and-coming players, including Jimmy McAleer, Bobby Lowe, and 18-year-old Clark Griffith, a future Hall of Famer. Horner and Griffith would become lifelong friends.

The Western Association was a pitchers’ league; the league batting average was .232 in 1888.21 Horner hit .162 and Warner batted .173.22 Horner’s won-lost record was 8-8 when he and Warner were released by Milwaukee in August. Later that month Horner pitched in two games for Omaha without Warner.

In the spring of 1889, Horner and Warner joined the New Haven, Connecticut, team of the Atlantic Association. Unfortunately, Warner threw his arm out that spring. He had married Carrie V. Whitter of Baltimore in December 1888, and now with a bad throwing arm, he decided it was time to retire from baseball. He and Carrie settled in Baltimore where he worked as a carpenter.23

Horner continued on and pitched for New Haven for three seasons, 1889-91. In 1890 he achieved an impressive 30-16 record. He coached the Yale baseball team in the spring of 1890 and 1891. His best pitcher on the 1890 Yale squad was Amos Alonzo Stagg, who would go on to an illustrious career as a college football coach.

The New Haven team disbanded in August 1891, and Horner accepted an offer to pitch for the 1892 Oakland Colonels of the California League. He and Lester German formed Oakland’s two-man pitching rotation, and they endured a brutal workload: 595⅓ innings pitched by Horner and 655 by German. Horner’s record was 30-34 with a 1.77 ERA. He was “considered the best fielding pitcher as well as the most brainy twirler in the California League.”24

Horner, with his dashing handlebar moustache, was popular with the ladies. The Oakland Tribune said he was “the handsomest player in the California League.”25 In February 1893 he married Catherine “Kate” Houghton, a California native. The young couple would have two daughters: Catherine Estella, born in 1895, and Anastasia Ruth, born in 1897.26

Horner and Clark Griffith formed Oakland’s two-man rotation in 1893, and each won 30 games before the California League folded in August. Horner logged 438 innings in league play and continued to pitch for an Oakland team until December. This included a series of exhibition games against the barnstorming Boston Beaneaters, the reigning National League champions.

In San Francisco on November 1, 1893, Horner pitched against the Beaneaters and nearly pulled off an upset. His team led, 2-1, entering the bottom of the ninth. Could he close out the heart of the Boston batting order? Hugh Duffy lashed a line drive that was snared by third baseman Jerry Denny for the first out. Tommy McCarthy singled and Jake Beckley doubled, putting runners on second and third. Horner uncorked a wild pitch and both runners scored, giving the Beaneaters a 3-2 victory.27

In four other contests against the Beaneaters, Horner dueled Boston ace Kid Nichols. Horner pitched well in each but won only one, on December 17 in San Francisco by a 5-2 margin.28

Horner pitched overhand and underhand (submarine style). Danny Long, scout for the Baltimore Orioles, was impressed. Long said:

“While Horner is a right-handed pitcher, his success against the left-handed batters of the Boston League team and those of the California League has been remarkable. He has absolute control of his slow ball, good raise and drop balls and a fast in-raise, which is very effective. Against left-handed hitting teams like Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Cleveland, he ought to be a star.”29

The Orioles signed Horner to a contract in January 1894. The good news was that he was going to the major leagues and getting a chance to play for his hometown team. The bad news was that he had worn his arm out, pitching more than a thousand innings in two seasons.

Horner was bothered by a sore arm at spring training with the Orioles, but by early May he declared that he was ready to pitch. In Baltimore on May 7, with the Orioles holding a 15-0 lead over the Washington Senators, manager Ned Hanlon put Horner in for his major league debut. He pitched the final three innings without allowing a hit. “He had not much speed, but his slow curves and twisters kept the Senators guessing,” said the Baltimore Sun.30

Four days later, Hanlon gave Horner his first major league start, against the Philadelphia Phillies in Baltimore. The Phillies won, 12-7. Horner went the distance, surrendering 14 hits and six bases on balls. “His slow, creepy curves bothered” the Phillies “for a few innings,” said the Sun, “but he had no speedy ball to sandwich in between them, and in the last half of the game the visitors hit him as they pleased.”31 The Philadelphia Times reported that Horner “had lots of funny curves, but he found a great deal of trouble in putting them over the plate and had [catcher Wilbert] Robinson dancing about trying to stop his erratic shoots.”32

It was apparent that Horner’s arm was not in condition. Hanlon advised him “to go to Atlantic City and take salt water baths” to help his arm, and return to the team when he was ready to pitch.33 Horner did as instructed and returned in June, and pitched well in an exhibition game on June 17.34 Unconvinced, Hanlon farmed him out to the Springfield, Massachusetts, team of the Eastern League.

Horner pitched in seven games for Springfield with little success. During the evening of July 29, he was out partying with teammates James Dolan and Roscoe Coughlin. The details of “their frolic” were not reported, but their behavior was somehow egregious. Horner and Dolan were fined $75 each by the Springfield club and released; Coughlin was fined $50 but retained.35 Horner finished the season on the Petersburg team of the Virginia League, and in late August it was reported that “his arm is gone.”36

Horner pitched in seven games for Springfield with little success. During the evening of July 29, he was out partying with teammates James Dolan and Roscoe Coughlin. The details of “their frolic” were not reported, but their behavior was somehow egregious. Horner and Dolan were fined $75 each by the Springfield club and released; Coughlin was fined $50 but retained.35 Horner finished the season on the Petersburg team of the Virginia League, and in late August it was reported that “his arm is gone.”36

Horner went to spring training with the Orioles in 1895 and was farmed out to the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association. With renewed strength, he compiled an 11-9 record and helped the Crackers win the pennant.37 He shut out Little Rock twice, with a one-hitter on May 29 and a five-hitter on June 11.38

The following spring, the Orioles sold Horner’s contract to Scranton, Pennsylvania, of the Eastern League. He tossed a four-hitter in Scranton’s victory over Springfield on May 2, 1896,39 but struggled mightily after that. He was “punished” by Providence hitters in a 12-3 loss on May 14 and “slaughtered” by Wilkes-Barre in a 22-6 debacle on June 2.40 The Scranton team was in last place on June 12 when Horner and his manager, Mike McDermott, were released.

McDermott became manager of the Bangor, Maine, team of the New England League and brought Horner with him, but Horner fared poorly and was released in July. He finished the season with Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in the same league and returned to Pawtucket the following season. At practice on July 1, 1897, he was struck in the face by a batted ball and knocked unconscious; it looked quite serious at first, but he recovered. Pawtucket, though, released him “to reduce expenses.”41

On March 3, 1898, Horner’s longtime friend and battery mate, Ed Warner, died of tuberculosis, leaving his widow and two sons.42 The end was at hand for Horner’s baseball career. He pitched briefly in 1898 for Taunton, Massachusetts, and Pawtucket before calling it quits.

In 1899 Horner was employed at city hall in Providence, and the next year he worked as a hotel clerk in New York City. He lived in Florida in 1904 and pitched for semipro teams in Jacksonville and Ocala, then found a permanent home in Atlanta in 1905, where he was the proprietor of a cigar store and a bartender in a saloon. He was a friendly and popular guy who umpired local baseball games, including spring exhibitions played by major league teams.

Horner also scouted for the Detroit Tigers. On July 14, 1910, while in New Orleans on a scouting assignment, he died at age 46 of a skull fracture he received when he slipped and fell onto the marble floor of a hotel. In a short obituary, Sporting Life noted that Horner started out in baseball accompanied by a catcher named Warner. “The two earned much fame as the ‘Horner and Warner’ battery, and for years they were inseparable.”43

Horner was buried at the Greenwood Cemetery in Atlanta.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Ancestry.com (accessed March 2020).

Photos: 1888 Old Judge baseball card of Jack Horner and Ed Warner (special thanks to Bob Richardson for providing the image); and Jack Horner later in life, Atlanta Constitution, July 15, 1910: 10.

Notes

1 Thomas Holmes, “Pitchers Trust to Luck and a Fast Outfield; Moore and DeBerry Star,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 24, 1929: 24.

2 Peter Morris, Catcher: How the Man behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009), 358.

3 “Ball Players Arriving,” Baltimore Sun, March 22, 1894: 2.

4 Baltimore Sun, January 23, 1894: 6, and March 22, 1894: 2.

5 “Base Ball,” Norfolk (Virginia) Landmark, October 1, 1884: 1.

6 “The Norfolks Cover Themselves with Glory,” Norfolk Landmark, October 11, 1884: 1.

7 Sporting Life, October 22, 1884: 6, and November 5, 1884: 4.

8 “Base Ball,” Norfolk Landmark, October 23, 1884: 1.

9 Sporting Life, November 26, 1884: 5.

10 “Rochester to the Front,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, June 6, 1886: 3.

11 Sporting Life, June 16, 1886: 2, and July 7, 1886: 8; “Five Runs and All Earned,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 3, 1886: 6.

12 “Threetees’ Meditations,” Sporting Life, June 16, 1886: 3.

13 “Hits Outside the Diamond,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 2, 1886: 6.

14 “Lost to Coal Heavers,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, June 22, 1887: 7.

15 “Ball Games, Good and Bad,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 1, 1887: 5.

16 “From Baltimore,” Sporting Life, August 31, 1887: 4.

17 Sporting Life, August 31, 1887: 6, and September 7, 1887: 6.

18 “Games and Pastimes,” Buffalo Commercial, October 10, 1887: 3.

19 Computed by the author from batting statistics published in Sporting Life, November 9, 1887: 3.

20 “The Season on the Diamond,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Leader, November 20, 1887: 2.

21 Computed by the author from batting statistics published in Sporting Life, December 12, 1888: 5.

22 Sporting Life, December 12, 1888: 5.

23 “Death of Ex-Catcher E.H. Warner,” Baltimore Sun, March 4, 1898: 6.

24 “Editorial Views, News, Comment,” Sporting Life, October 29, 1892: 2.

25 “The Umpire,” Oakland Tribune, December 14, 1892: 8.

26 1900 US Census.

27 “One More for Boston,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 2, 1893: 5.

28 “J. Frank Horner Plays Ball,” San Francisco Examiner, December 18, 1893: 5.

29 “Base-Ball,” Baltimore Sun, January 23, 1894: 6.

30 “A Batting Fusilade,” Baltimore Sun, May 8, 1894: 6.

31 “Philadelphia Again,” Baltimore Sun, May 12, 1894: 6.

32 “Once More Philadelphia,” Philadelphia Times, May 12, 1894: 8.

33 “Hanlon’s Hope,” Sporting Life, June 2, 1894: 3.

34 “The Field of Sport,” Baltimore Sun, June 18, 1894: 6.

35 “Diamond Points,” Fall River (Massachusetts) Evening News, August 2, 1894: 4.

36 “Chasing the Pennant,” Norfolk Virginian, August 28, 1894: 2.

37 Marshall D. Wright, The Southern Association in Baseball, 1885-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002), 57.

38 Sporting Life, June 8, 1895: 17, and June 22, 1895: 17.

39 “Scranton Won Saturday’s Game,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Times, May 4, 1896: 3.

40 “Horner Punished,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Republican, May 15, 1896: 3; “Yellowest Kind of Ball Playing,” Scranton Times, June 3, 1896: 3.

41 “Pawtucket Points,” Sporting Life, July 10, 1897: 6.

42 Baltimore Sun, March 4, 1898: 6; 1900 US Census.

43 ‘Horner Killed.” Sporting Life. July 23, 1910; 7

Full Name

William Frank Horner

Born

September 21, 1863 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

Died

July 14, 1910 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.