Justin Fitzgerald

Justin Fitzgerald was small. Had a bad arm. Even a bad leg. Even caught the Spanish Flu. Yet he managed to hit over .300 for close to a decade with the San Francisco Seals, winning acclaim as one of the fastest and most exciting players in the Pacific Coast League in the 1910s. He was a reserve outfielder with the New York Highlanders (1911) and Philadelphia Phillies (1918). The baseball lifer also taught players how to play the game — hard. Leave it all on the field.

Justin Fitzgerald was small. Had a bad arm. Even a bad leg. Even caught the Spanish Flu. Yet he managed to hit over .300 for close to a decade with the San Francisco Seals, winning acclaim as one of the fastest and most exciting players in the Pacific Coast League in the 1910s. He was a reserve outfielder with the New York Highlanders (1911) and Philadelphia Phillies (1918). The baseball lifer also taught players how to play the game — hard. Leave it all on the field.

Justin Howard Fitzgerald (who has been called “Mike” in some baseball references1) was born on June 26, 1891, in San Mateo, California. He was the youngest of five children born between 1881 and 1891 to Thomas and Teresa Fitzgerald. Irishman Thomas was a teamster and American Teresa was a housekeeper. Teresa likely cleaned houses for some of the wealthy San Franciscans whose mansions served as weekend and summer homes after the San Francisco and San Jose railroad opened. It took 37 minutes to go from the City to San Mateo.2 Eldest son Alfred (born Harold T.) was an electrician in his late teens. Three daughters then followed — Ellen, Amelia, and Margarete (Reta).

San Mateo, which Justin would call home for most of his life, was a sleepy town of 10,000 when he was born. It grew to over 100,000 people by the time of his death in 1945. The town benefited from the 30-minute train ride south from San Francisco and also grew following the Great Quake and Fire of 1906, when residents wanted to leave the big city behind.3

Little is known of Justin’s youth. He attended San Mateo High, which in 1907 had 90 students enrolled. It had lost no class time from the Great Quake because the school building was one of the first to be repaired4. His first professional experience came at 19; he commonly “punched out three hits a game,” and led the Three C League at .410 for Watsonville in the summer of 1910.5 Fitzgerald was discovered by Highlanders manager Hal Chase in a pickup game at Santa Clara College in January 1911. Chase sent his friend William Benson to sign the speedy outfielder. This established a common theme throughout Fitzgerald’s career: always looking for a better deal. He wanted to finish college and his relatives were “dead set against” a baseball career. He said that if he changed his mind, the Highlanders would get first crack.6

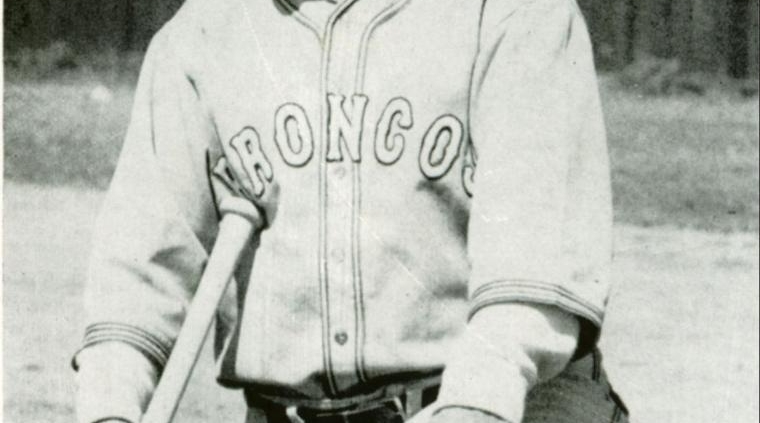

Fitzgerald graduated from San Mateo High in 1910. He patrolled center field for Santa Clara College for one season in 1911, hitting .444 for the 9-9-1 Broncos7 under Coach Bobby McHale. The leadoff hitter “proved himself marvelously fast getting [to] difficult flies.”8 He would later coach at Santa Clara and USF and his teams would take on the persona of their coach.

By April 1911, Fitzgerald had turned down offers from six big league teams, including the Cubs and Highlanders.9 He was “very fast on his feet,” but stood only 5-foot-9 and weighed 155 pounds.10 Considered one of the “greatest ballplayers in amateur or semiprofessional circles” in California,11 he finally signed a New York contract for $385 per year, the largest for an amateur on the West Coast.12 The available records show that Fitzgerald went straight to the majors. He made his debut as a substitute left fielder on June 20, 1911, going 0-for-3 with an RBI against Red Sox right-hander Charley Hall. Fitzgerald entered the game in the third and his RBI groundout in the ninth put two outs on the board in what was then, an 8-5 Red Sox lead. New York did not make another out, scoring four times for a 9-8 win.13

For the prior week or so, Fitzgerald had sat on the bench. He realized that to stay in the big leagues “you have to know the game backward.” He expected to ride the pine for five years, saying to a friend that many of his teammates were in the “same boat” as him.14 Instead, he started five straight games in left from June 21 through June 24. He hit safely in each of those games, and as a pinch-hitter in his next assignment, raising his average to .381. He stole three bases as well, including two in one game off Washington catcher Gabby Street in the second game of a doubleheader on June 24. Almost immediately after that game, however, his right arm was sore. He pinch hit in seven of eight games from June 27 through July 13, going 2-for-12.

The arm never healed. “An outfielder without a good arm can’t find a berth here,” he told an Oregon paper.15 In July he was traded with Ed Klepfer and cash to Sioux City in the Western League. Shortly after the trade, he said in a letter to a friend, “[T]here are a bunch of older men on the [New York] team, however, and I guess [Chase] didn’t want to take a chance on me developing.”16 He hit .240 in 29 games for Sioux City before returning to New York in late August. (No record was found of the terms of his return.)

Fitzgerald had two hits against the Browns in St. Louis in a pair of starts on August 28 and August 29. He appeared twice more for New York and finished his season with the 1911 Highlanders batting .270 with six runs and six RBIs in 16 games. On September 15 he was sent to Jersey City in the Eastern League. He robbed an opponent of a home run in his first game there but struggled at the plate. He then filed a claim with the National Baseball Commission for his salary with the Highlanders from September 25 to October 8 — and eventually won that claim.17

Another controversy arose the following winter. He was traded to the Oakland Oaks for Harry Wolverton. Believing he was getting his release, Fitzgerald went hunting (and got blood poisoning on the trip).18 He refused to play for the Oaks and what he called their “pork and beans” lowball contract.19 His options became playing for an independent outlaw team in San Jose,20 if he was given the same salary as in organized ball, or a semipro team out of Watsonville called the Snowden Giants. He chose Snowden before joining Portland in the Coast League in July 1912.21

In Portland, the “speed merchant” was beating out bunt base hits and hitting .330 (14-for-40) as of late August.22 In one memorable game he stole second, third, and home in the 10th inning, and finished the doubleheader sweep of Sacramento by going 4-for-6.23 His speed was being noticed. To Oaks manager Bud Sharpe, he was the “fastest man in the Pacific Coast League… You have to be alert to catch Fitzgerald on an infield tap. I never realized that he was so fast until I saw him play against us.”24 He hit .355 with 13 steals, 26 runs, and seven doubles in half a season with the Beavers.

During the winter, Fitzgerald saw an arm specialist while also coaching at St. Thomas College, a small school in San Francisco. By the season’s start, Portland manager Walter McCredie was relieved that no one picked him up, saying, “[If] that lad isn’t worth $5,000 to some big league club, he isn’t worth a cent.”25 Fitzgerald was becoming a fan favorite as well. One fan wrote he was a “daring base runner (taking)… advantage of every misplay.”26 Another said he was “away from the plate like a flash.”27 He was also starting to get his business affairs in order, purchasing property at Hayward Park in the Bay Area for $3,000.28

Though his arm continued to hurt, he refused surgery. He worked even harder each morning, “pounding the ball around” batting practice but also striking out.29 After appearing in 35 games with the Beavers, in June he was sent down to the Portland Colts in the Class B Northwestern League. In his first game, he had two hits, two steals, and made a nice catch.30 The “hardest man to pitch to in the Northwestern League” walked 32 times in 47 games.31 But he was released in early August, hitting just .266, tthen caught on with Spokane in the same league a few days later. With a “touch of revenge,” he had a ninth-inning RBI against Portland soon after.32 Towards the end of August, Fitzgerald hurt his leg and called it a year in Spokane. He ended up in the semipro Trolley League for Chico in September with a handful of prospects in Northern California.33

Fitzgerald became a carpenter in San Mateo, figuring he was done in pro ball, but manager Del Howard and the 1914 San Francisco Seals needed an outfielder. The fourth-place Seals took a chance and assembled an outfield of five players under 25 in training camp.34 Though the Seals had found a piece of their championship puzzle, the former carpenter could not rebuild his right arm. He began experimenting with throwing left-handed.35 At times throughout the rest of his career he would spend 15 minutes a day throwing with his left arm. It was not unheard of: both Edd Roush and Tris Speaker changed throwing arms and excelled in the majors.36

From 1914 to 1921 the Seals produced six winning seasons, winning the PCL championship twice (1915, 1917). One of the two losing seasons (1918) came when Fitzgerald was with the Phillies. The other, 1919, was a year after Fitzgerald was recovering from the Spanish flu. The 1914 Seals were off to a hot start, and Fitzgerald was hitting .400 through the first 28 games. The Seals were on the heels of Venice for the Coast League lead.37 Hitting .337 in late June, Fitzgerald cooled, finishing at .308 as the Seals’ prospects sank to third. He amazed Coast fans by stealing four bases in one game, including, second, third and home against the Beavers.38

Fitzgerald signed to play winter ball in Hawaii for three weeks with Happy Hogan’s Venice Tigers.39 The Honolulu trip began a scouting career. He saw a left fielder named Lang Akana, whose mother was Hawaiian and father was Chinese. Fitzgerald sent a letter to Beavers manager McCredie about a hard-hitting, good-fielding, fast player on the island. Akana’s dark skin did not allow him much of a chance in professional baseball, but three years later, he was the first Chinese player to play pro baseball in America.40

During his time with San Francisco, other Fitzgerald scouting finds included:

- Infielder Sam Bohne, who joined the Seals in 1915 at age 18 and eventually became a four-year starter for the Reds in the 1920s.

- Catcher Forrest Cady, who signed with the Seals in 1919 and ended up being a backup catcher for seven years in the major leagues.

- Second baseman Lew Fonseca, who started with the Seals in 1920 and whose 12-year big league career included a .316 average and 103 RBIs in 1929 for the Indians.41

Fitzgerald began 1915 as the team’s leadoff hitter and right fielder. Out of spring training, Ping Bodie, Biff Schaller, and Fitzgerald formed “one of the hardest-hitting outfields in the league.”42

His bum arm sometimes surprised opponents. Against Venice in early April he “saved the day by his perfect throw [home]” and catch against the outfield wall.43 He scored 23 runs in the first 26 games; by June he was third in the league in steals (19) and second in runs (53) while hitting .345 for the first-place Seals. A leg injury in late June caused him to miss about 20 games, but San Francisco nonetheless secured the Coast title, and Fitzgerald’s athleticism in the outfield showed during the September push, as he made a seemingly impossible catch by climbing up the piping against Portland.44 The Seals finished in first place with 118 wins. Fitzgerald posted a .321 batting average with 28 doubles, nine triples, and nine homers.

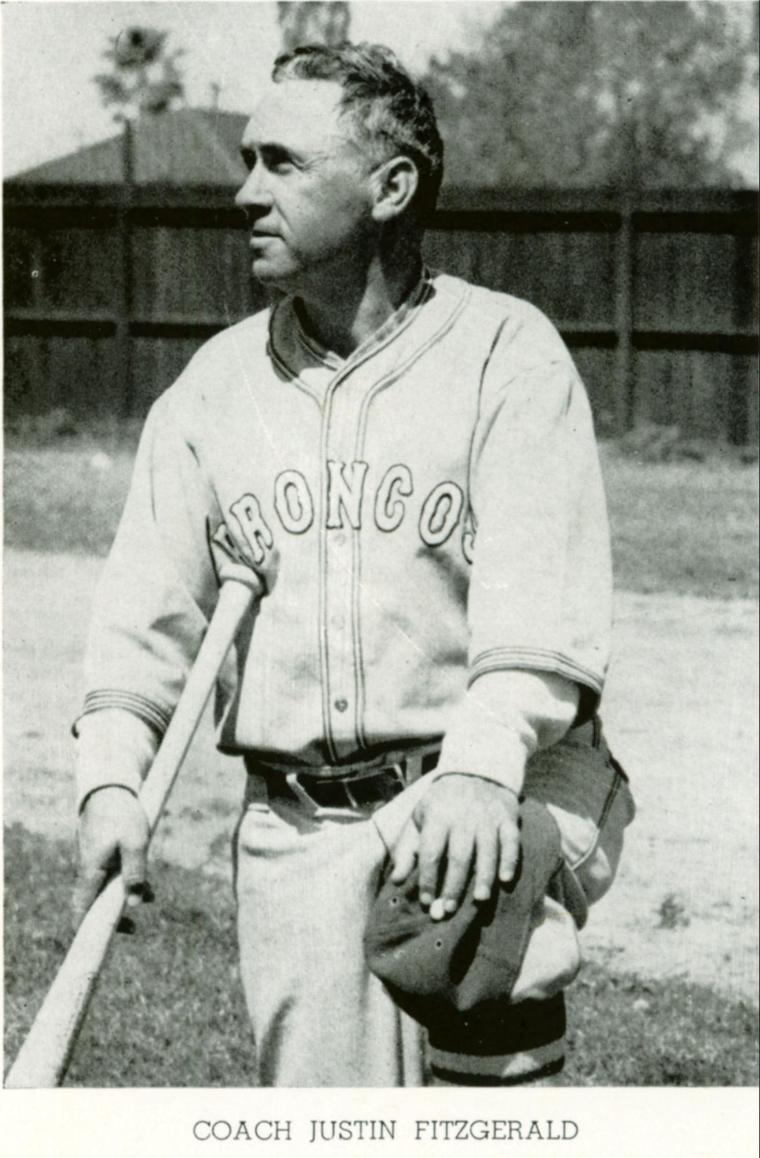

The 1916 Seals outfield again featured Schaller and Bodie — and eventually Fitzgerald, who secured head coaching duties at Santa Clara and again was a holdout. He trained with the Seals in the morning and then took the train down to Santa Clara, where practice did not begin until 3:30 p.m.45 Fitzgerald coached the Broncos off and on for the next 24 years between 1916 and 1939. He not only taught his teams the fundamentals but also “instilled into them that fighting spirit [that] made them battle until the last man was out.”46

Fitzgerald again was the fastest man in the PCL in 1916. He was batting .353 with a league-leading 17 steals when he tore a ligament sliding into second base in mid-May. It was feared he would be out for the year.47 One paper reported that it took the rest of the Coast base stealers a month to catch him in steals.48 In June, Connie Mack’s Athletics were interested in the outfielder. He was still just 26, but his arm “prevented him from ranking with the greatest stars of the game.”49 Working out in mid-July in Los Angeles, he reinjured the leg and was delayed a few more weeks.50 He finally returned to the lineup on August 12 as a pinch hitter and finished the 1916 season at .316.51 His reputation became one of a “frail ballplayer” who might never return to the majors.52

Ahead of the 1917 season, Fitzgerald again was in no hurry to sign. He finally did so in late January.53 He found another interest as a fight promoter at San Mateo’s Rose City Athletic Club, and continued promoting bouts into the season, sometimes with outfield mate Bodie as judge.54

In July, hitting .350, he was subject to being drafted by the Army for World War I.55 By September, another draft, this time the Rule Five draft, had him going to Philadelphia — but the Phillies rather than the A’s.56 The Phillies were coming off a second-place finish. Manager Pat Moran expected Fitzgerald to be a regular in the outfield with Irish Meusel and Cy Williams.57 However, Fitzgerald returned his first contract unsigned, and the Phillies countered by threatening to blacklist him and cancel the draft.58 He then returned the second and third contracts as well.59 Meanwhile, the Phillies were losing players in St. Petersburg to injury, sickness, and the military.60 Fitzgerald finally signed.

Over his first month, he hit .255 with 11 starts in the 19 games in which he played. On May 29, Fitzgerald was granted the day off and married Ruth Woolley of Salt Lake City. Meusel and his wife served as best man and matron of honor. The following day, Fitzgerald delivered a pinch-hit single in a 6-3 loss to the Giants.61 In late June he was called a key pinch-hitter for the club who should start.62 However, he did not get another start until late July, and finished the year at .293, the only year he would finish below .300 between 1914 and 1921.

Fitzgerald returned to the Bay Area in late September and was playing for the Mare Island military team when he became one of the first to catch the Spanish flu in October 1918, while his wife was pregnant.63 Cases jumped in San Francisco from 169 to 2,000 in just one week in mid-October as Mayor James Rolph put social distancing and later masks in place and the city shut down “all place of public amusement.” With 3,000 eventual deaths, it was one of the harder hit U.S. cities.64

Before the 1919 season, Fitzgerald felt like “a chicken with the pip” who could not shake the “languid feeling.”65 He had negotiated his release from the Phillies in February, and signed with the Seals.66 Fellow Santa Clara alum and manager Walter Graham needed two outfielders. The Seals were coming off their first losing season in six years (51-52), and Fitzgerald had a family to think about.67 On March 23, he welcomed his firstborn, Justin, Jr. In celebration, he “danced around the depot platform.”68

Proving at age 28 that he could still “win as many ball games on the bases as any outfielder in the League,” Fitzgerald was among Coast leaders in runs and steals.69 In an August game against Vernon, he stole second and third and then scampered home on a wild pitch in a 5-4 win in the 11th inning.70 Five days later he made a sensational catch in right field, causing a father to jump up in excitement, knock over a water bucket meant for a fire, and drench the fans as the “grandstand resembled an arm of the Pacific Ocean.”71

The Seals’ top hitter at .334, he quickly signed a 1920 contract despite rumors that he would be used only as a pinch hitter.72 For the next two seasons the “fastest old man in baseball”73 continued to hit above .300 for the Seals. In 1922, with his arm just about gone, he was traded to Sacramento for former journeyman major league outfielder Pete Compton.74 Fitzgerald continued to hit hard grounders and beat out infield singles. He even was acting manager in place of Charlie Pick after Pick broke his leg. Fitzgerald finally quit baseball in late July.75 Ten years later he told the Santa Clara student publication The Redwood, smiling, “When your arm is shot, you’re through.”76

Fitzgerald continued to serve as a scout for the Detroit Tigers. His most notable find: third baseman Marv Owen, whose play for the great Tigers teams of the mid-1930s led owner Walter Briggs to consider Owen “the greatest third baseman in the auto city’s history.”77 He was a founder of the semipro California State League, managing the San Mateo Blues to frequent league championships between 1924 and 1935.78 He also served on the San Mateo City Council from 1933 to 1937.

In addition to his tenure as a coach at Santa Clara, Fitzgerald was a coach at the University of San Francisco from 1941 until his death in 1945. He was viewed as a key hire for athletics director and former Olympics coach James Needles in the midst of World War II, “proving the faith in sports and thinking baseball will have a banner year.”79 However, USF struggled financially during the war years. Con Dempsey, who was on the Dons then and later pitched for the Seals and Pittsburgh Pirates, said later, “[USF] had a baseball team but it was a catch-me-if-you-can type thing. You got a towel to shower with and you dressed and undressed in a barracks they had there. There was not baseball there at all, for that matter… [Fitzgerald would] coach for maybe four of five weeks and then we would have somebody else. We were never subsidized by the athletic department.”80

On January 18, 1945, at 4:30 a.m. at Mills Hospital in San Mateo, Fitzgerald lost his month-long battle after a series of stomach operations. His death meant so much to the local community that the Winter League’s games were canceled the next Sunday and a plaque was placed in his honor at the base of an oak tree in center field. He was known as “one of baseball’s most loved and respected gentlemen.”81

Fitzgerald had three sons. After Justin, Jr. came Sterling (“Buzz,” born in 1921 or 1922) and Tommy (born in 1929). Justin, Jr., was stationed in England during World War II and lived until 87, dying in 2006. Buzz, a Marine, fought for 13 months in World War II, including being a part of the Guadalcanal campaign. Tommy fought in Korea and died in a car crash at 27 in 1956. Ruth Fitzgerald lived into her 90s, until 1984.82

After Justin Fitzgerald’s death, the Central Park field became known to locals as Fitzgerald Field. A formal dedication occurred on August 21, 1960. Tributes came to his wife, Ruth, including one from Philadelphia Eagles Coach Buck Shaw, who called him an “inspiration to youth.” American League president and one of the game’s best shortstops, Joe Cronin, called Fitzgerald one of his boyhood heroes.83

Fitzgerald is a member of three Halls of Fame: Santa Clara Athletics (1979), the City of San Mateo (1994) and San Mateo High Sports (2007). San Mateo Times sports editor Harvey Rockwell described him as “quiet, studious, gentlemanly and tolerant with a kind sense of humor.”84 He was also a fierce negotiator and hard-playing competitor until the end.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com and the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

Notes

1 Research has not uncovered anything to substantiate this nickname or its origins.

2 “More History of San Mateo.” City of San Mateo. Accessed May 17, 2020. https://www.cityofsanmateo.org/291/More-History.

3 “San Mateo County,” Bay Area Census, Accessed May 17, 2020. http://www.bayareacensus.ca.gov/counties/SanMateoCounty50.htm.

4 “San Mateo High School History,” San Mateo High, accessed November 29, 2020. https://www.smuhsd.org/Page/961.

5 “Santa Clara Boy Now Big Leaguer,” San Francisco Call Bulletin (San Francisco, CA), April 9, 1911: 41.

6 Chris Goode, California Baseball from the Pioneers to the Glory Years. 9th ed. no publisher, 2009: 151-52.

7 “Post Season Baseball at Santa Clara,” San Francisco Call Bulletin (San Francisco, CA), April 22, 1911: 17.

8 The Redwood. Vol. 10. Santa Clara, CA: Santa Clara University, 1910-11: 275 http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/redwood/10.

9 Evening Star (Washington DC), April 6, 1911: 17.

10 “Santa Clara Boy Now Big Leaguer,” San Francisco Call Bulletin (San Francisco, CA), April 9, 1911: 41.

11 “Santa Clara Boy Now Big Leaguer,” San Francisco Call Bulletin (San Francisco, CA), April 9, 1911: 41.

12 “Timeline 1910-11.” Timelines of History. Accessed October 10, 2019. https://www.timelines.ws/20thcent/1910_1911.HTML.

13 “Yankees Never Say Die,” New York Daily Tribune (New York City, NY), June 21, 1911: 9.

14 “Ping Bodie Talks up New York,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), June 11, 1911: 2.

15 R.A. Cronin, “Fitz Getting Arm Back Into Shape,” Oregon Journal (Portland, OR), March 21, 1913: 16.

16 F.A. Purner, “Fitzgerald is Traded,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), July 20, 1911: 8.

17 “Baseball Briefs,” Jersey Journal (Jersey City, NJ), March 5, 1912: 7.

18 R.A. Cronin, “Fitz Getting Arm Back Into Shape,” Oregon Journal (Portland, OR), March 21, 1913: 16.

19 “Portland Youngster Who Richly Deserves Nickname of ‘Flash’,” Oregon Journal (Portland, OR), September 1, 1912: 21.

20 “Stanford Coach to Play Outlaw Ball,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), January 17, 1912.

21 “Bush Midwinter League to Start Again,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), July 14, 1912: 51.

22 “Fitzgerald On Way,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), August 25, 1912: 3.

23 “Entire Series is Taken by Beavers,” The Oregonian (Portland, OR), August 26, 1912: 8.

24 “Giants are Picked,” The Oregonian (Portland, OR), September 20, 1912: 8.

25 “Fitz’s Arm Worked –Anderson Meets Good Boy,” Oregon Journal (Portland, OR), January 16, 1913: 16.

26 J.A. Menzies, “Letter from a Distant Friend,” Yale Expositor (Yale, MI), February 13, 1913: 6.

27 “Hig, Hag and Stan are Rushed Against Oaks, But Game is Clinched,” Oregon Journal (Portland, OR), April 10, 1913: 16.

28 “Swain May Play in North,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), August 3, 1913: 2 and “Fitzgerald to Go,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), January 26, 1913: 4.

29 “McCredie Starts to Build Up Team,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), April 24, 1913: 9.

30 “Fitzgerald Breaks in Auspiciously with Colts as Nick Shifts His Outfield,” Oregon Journal (Portland, OR), June 11, 1913: 16.

31 Oregonian (Portland, OR), October 5, 1913: 6

32 “Fitzgerald to Go,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), August 3, 1913: 2 and “Colt Pitcher Whose Reappearance in Baseball Under a Playing Name is Puzzling to Fans,” Oregonian August 10, 1913: 7.

33 “Williams Not to Be Sold by Atkin,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), August 27, 1913: 7 and James Nealon, “Stars of the Trolley League Stir Interest in of Scouts,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), September 21, 1913: 64.

34 Fred Purner, “Howard Departs for Training Camp,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), February 8, 1914: 57.

35 “Former Veteran Angel is Added to Hurling Staff,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), January 31, 1914: 10.

36 Ed Hughes, “George Coleman is a Reconstructed Athlete,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), March 9, 1922: 14 and “Baseball Brevities,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), April 13, 1920: 14.

37 “Seal Hitter Leads Pacific Coasters,” Arizona Republic (Phoenix, AZ), May 19, 1914: 3.

38 “Locals are Hard Pressed to Beat the Beavers,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), October 25, 1914: 51.

39 “Seen from the Press Box,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), November 7, 1914: 5.

40 “Beavers Sign to Play Negro Stars,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), January 15, 1915, 14 and “There Is Only One Thing against Him – He Is Very Dark.” Baseball History Daily. Last modified July 13, 2016. Accessed November 12, 2019. https://baseballhistorydaily.com/2016/07/13/there-is-only-one-thing-against-him-he-is-very-dark/

41 Ed Hughes, “Forrest Cady to Catch for Local Club,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), February 20, 1919, 14 and Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia, PA), March 19, 1921: 15 and “Totterling Along,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), May 12, 1921.

42 “Oakland Becomes a Pennant Contender; New Men are Added,” Oregon Journal (Portland, OR), March 30, 1915: 8.

43 “John Couch Shows Against Venice Tigers,” Salt Lake Telegram (Salt Lake City, UT), April 8, 1915: 7.

44 “Seal Team is Very Much a Hospital Crew,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), July 6, 1915: 5 and Harry Smith, “Three Rousing Cheers! Seals Tumble Back in Lead,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), September 4, 1915: 6.

45 Harry Smith, “Fitzgerald and Wolverton Reach Terms” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), January 22, 1916: 6.

46 The Redwood. Vol. 26. Santa Clara, CA: Santa Clara University, 1926-27: 171.

https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=redwood

47 “Seal Outfielder Fitzgerald Badly Hurt,” Capital Journal (Salem, OR), May 18, 1916: 11.

48 Jim Nasium, “Miles Mains Skips Out of Phils’ Camp,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), March 30, 1918: 14.

49 “Fitz Had his Ups and Downs,” Salt Lake City Telegram (Salt Lake City, UT), June 18, 1916: 15.

50 “Fitzgerald Unlucky,” Seattle Daily Times (Seattle, WA), July 19, 1916: 15.

51 “Ping Bodie’s Wild Heave Brings Seal Defeat,” Salt Lake City Telegram (Salt Lake City, UT), August 13, 1916: 29.

52 “All Stars Among Coasters Chosen,” The Oregonian (Portland, OR), October 29, 1916: 4.

53 “Fitz Awaits Developments,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), January 27, 1917: 8.

54 “Bits of Sport,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), February 3, 1917: 6.

55 “Some Celebrities of the World of Sport Summoned to the Colors by Draft Lottery,” Omaha Daily Bee (Omaha, NE), July 29, 1917: 32.

56 “An Ear to the Ground,” Salt Lake City Telegram (Salt Lake City, UT), August 9, 1917: 16.

57 “Justin Fitzgerald to Play with Pat Moran,” Washington Times (Washington DC), January 19, 1918: 14.

58 “Seal Fielder Wants to Stay,” Tacoma Times (Tacoma, WA), February 28, 1918: 7.

59 “Fitzgerald Rejects Last Philly Contract,” Riverside Daily Press (Riverside, CA), March 15, 1918: 8.

60 Jim Nasium,, “Phils Running Shy of Players,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), March 23, 1918: 14.

61 “Justin Fitzgerald Weds,” Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia, PA), May 30, 1918: 10.

62 “Fluke Hits Mar Coomb’s Record,” Evening Public Ledger (Philadelphia, PA), June 26, 1918: 12.

63 “Fitzgerald is Youngest Player of Them All,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), March 9, 1920 and “Sports of All Sorts,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), October 25, 1918: 12.

64 Darturnorro Clark, “San Francisco had the 1918 flu under control. And then it lifted the restrictions.” NBC News.com, April 25, 2020, accessed May 15, 2020, https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/san-francisco-had-1918-flu-under-control-then-it-lifted-n1191141.

65 “Fitzgerald is Youngest Player of Them All,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), March 9, 1920

66 “Seals Get Fitz,” Evening Tribune (San Diego, CA), February 21, 1919, 10 and “Fitzgerald Wants More Money if He Plays Here Again,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), February 10, 1919: 8.

67 “Graham Wants Outfielder, Good Leadoff Man,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), January 26, 1919: 11.

68 Ed Hughes, “Big Crowd is on Deck for 2 Baseball Games,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), March 24, 1919: 8.

69 “San Francisco Looks Dangerous, But Slow,” Seattle Daily Times (Seattle, WA), April 6, 1919: 72.

70 United Press, Capital Journal (Salem, OR), August 6, 1919: 6.

71 “Walker Well Up,” Oregon Journal (Portland, OR), November 19, 1919: 44.

72 “Fitzgerald Signs His 1920 Contract,” San Francisco Chronicle (December 7, 1919: 100.

73 “Beavers Grieve in Ninth,” Oregonian (Portland, OR), April 29, 1920: 12.

74 “Compton Joins Frisco in Trade,” Evening Tribune (San Diego, CA), May 22, 1912: 15.

75 “Here and There in the League of All Sports,” Evening News (San Jose, CA), July 25, 1922: 9.

76 The Redwood, Vol. 26. Santa Clara, CA: Santa Clara University, 1926-27: 171.

https://scholarcommons.scu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=redwood

77 Bob Stevens, “Fitzgerald Passes Away in San Mateo.” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), January 19, 1945: 15.

78 Jim Clifford, “The Blues Brought Cheers to San Mateo,” Daily Journal, April 22, 2019, accessed May 15, 2020 https://www.smdailyjournal.com/news/local/the-blues-brought-cheers-to-san-mateo/article_65588e98-64b2-11e9-b4e4-0bce6cacedbe.html.

79 “Needles Makes Wise Move,” The Foghorn, San Francisco, CA, February 19, 1943: 5.

80 Brent Kelley, The San Francisco Seals, 1946-57. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2002:106.

81 Bob Stevens, “Fitzgerald Passes Away in San Mateo.” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), January 19, 1945: 15.

82 Bob Stevens, “Fitzgerald Passes Away in San Mateo.” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), January 19, 1945: 15.

83 Buck Shaw to Ruth Fitzgerald Telegram, August 21, 1960, Fitzgerald Field Memorable Games PDF, https://cdn3.sportngin.com/attachments/document/0073/0649/Fitzgerald_Field_-_Memorable_Games.pdf and Joe Cronin to Dave McCulloughj Telegram, August 19, 1960, Fitzgerald Field Memorable Games PDF, https://cdn3.sportngin.com/attachments/document/0073/0649/Fitzgerald_Field_-_Memorable_Games.pdf.

84 Jim Clifford, “The Blues Brought Cheers to San Mateo,” Daily Journal, April 22, 2019, accessed May 15, 2020 https://www.smdailyjournal.com/news/local/the-blues-brought-cheers-to-san-mateo/article_65588e98-64b2-11e9-b4e4-0bce6cacedbe.html.

Full Name

Justin Howard Fitzgerald

Born

June 26, 1891 at San Mateo, CA (USA)

Died

January 18, 1945 at San Mateo, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.