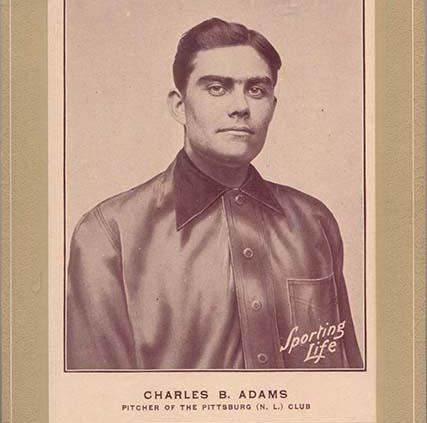

Babe Adams

Best remembered for pitching three complete-game victories as a rookie to help the Pittsburgh Pirates win the 1909 World Series, Babe Adams was one of the Deadball Era’s greatest control pitchers. His record of 1.29 walks per nine innings over the course of his 19 years in the majors, 18 with the Pirates, ranks second on the modern list behind only teammate Deacon Phillippe‘s 1.25. To put Adams’ mark in perspective, the preeminent control pitcher of recent years, Greg Maddux, would have had to pitch another 217 consecutive nine-inning games without a walk to lower his lifetime walks per nine innings to the same level.

Best remembered for pitching three complete-game victories as a rookie to help the Pittsburgh Pirates win the 1909 World Series, Babe Adams was one of the Deadball Era’s greatest control pitchers. His record of 1.29 walks per nine innings over the course of his 19 years in the majors, 18 with the Pirates, ranks second on the modern list behind only teammate Deacon Phillippe‘s 1.25. To put Adams’ mark in perspective, the preeminent control pitcher of recent years, Greg Maddux, would have had to pitch another 217 consecutive nine-inning games without a walk to lower his lifetime walks per nine innings to the same level.

Charles Benjamin Adams was born in Tipton, Indiana, on May 18, 1882. “My early boyhood in Indiana was spent on a farm,” he told reporters after the 1909 World Series. “I did my bit down on that farm, too; we all did, and dad always saw that the work was well done.” Charley was actually born left-handed, but he developed his right hand by throwing stones at tree stumps and rabbits after a childhood accident nearly severed the little finger of his left hand. At age 16 he went to live with Lee Sarver, a farmer in Mount Moriah, Missouri, a tiny town in the northwest corner of the state. Encouraged by Sarver, Charley played for the high school baseball team and later pitched for the local town team. A seamstress made red velvet uniforms for him and his catcher; all the other players wore overalls.

After Adams was beaten badly in a 1904 game against the team from Lamoni, Iowa, Walter Steckman, the opposing shortstop, showed him (in the words of a 1909 newspaper article) “how to grasp the ball for the different twists and to let loose the whirlers which had so mystified the boys.” Charley practiced throwing his new curveball against a barn door. The effort paid off when a local umpire who doubled as a talent scout recommended him to the Class C team from Parsons, Kansas, of the Missouri Valley League. It was a long way from the majors, but Charley was so anxious to report for the 1905 season that he did so while the ground was still snow-covered. He even helped build the grandstand and paint the signs on the outfield fence while waiting for his teammates to arrive. The wait proved worthwhile, as Charley pitched a one-hit shutout in his first game. He went on to win 21 games for Parsons, prompting the St. Louis Cardinals to purchase his contract.

Adams opened the season with the big league club, making his major league debut on April 18, 1906. He started and lost what turned out to be his only outing for St. Louis, going four innings and giving up six runs to the juggernaut Chicago Cubs. Ten days later the Cards sent Adams to Louisville of the Class AA American Association, which immediately released him to the Denver Grizzlies of the Class A Western League. He remained with Denver through 1907, the year he led the Western League in wins (24) and winning percentage (.649). The Pittsburgh Pirates purchased Adams’ contract for $5,000 at the tail end of that season and pitched him in four games, not enough for him to shake his rookie status. Loaned back to Louisville for 1908, he went 22-12 and walked only 40 batters in 312 innings.

By that point Adams had been tagged with the nickname “Babe,” though its precise origin remains uncertain. According to one story, his Denver teammates pinned it on him in 1907 after a woman asking for his autograph told him he had a nice round face like a baby’s. But James Skipper Jr., in his book Baseball Nicknames, states that Adams earned the sobriquet during his 1908 Louisville stint because female fans hollered “Oh, you babe!” whenever he took the mound. Either way, the dark-featured Adams apparently was popular with the ladies, and many hearts must have broken when he married Blanche Wright, his high school sweetheart from Mount Moriah, shortly before training camp in March 1909.

As a 27 year-old rookie, Adams pitched mostly in relief and helped the Pirates win the pennant by pitching 130 innings and compiling a 12-3 record with a stunning 1.11 ERA, a record for rookies that still stands. Nonetheless he was still a relatively unheralded member of a pitching staff that included Vic Willis, Howie Camnitz, Lefty Leifield, Deacon Phillippe, and Sam Leever, so Fred Clarke‘s decision to start him in Game One of the World Series against the Detroit Tigers came as a shock. According to legend, NL president John Heydler had seen Washington pitcher Dolly Gray hold Detroit scoreless for 18 innings in a game earlier that season and suggested to Clarke that Adams and Gray were similar in style (ignoring the fact that Babe was a righthander and Gray a lefty!). But Honus Wagner biographers Dennis and Jeanne DeValeria contend that it was simply Adams’ extraordinary composure and terrific final two months of the season (when he went 7-2) that led Clarke to his decision.

Surviving a ragged first inning in which the Tigers scored their only run of the game, and with the assistance of a great defensive play by center-fielder Tommy Leach in the seventh, Adams fed the Tigers a steady diet of low curves and pitched a complete game six-hitter, winning 4-1. In Game Five he was as sharp as he had to be, giving up four runs but striking out eight in a six-hit, 8-4 victory that gave the Pirates a 3-2 lead in the Series. In the seventh and final game at Detroit’s Bennett Park, Adams again yielded just six hits in an 8-0 shutout. The rookie from Mount Moriah had won three games in a World Series, a feat that no rookie has duplicated to this day.

Adams followed up his 1909 heroics with an 18-9 season in 1910 and 20-win seasons in 1911 and 1913, establishing himself as one of the NL’s best pitchers. Perhaps his greatest performance came on July 17, 1914, against the Giants and Rube Marquard, when he pitched 21 innings, walked none, and still lost a 3-1 decision. The game may have had negative consequences for both pitchers; Marquard lost 22 games that year while Babe’s record slipped to 13-16. The following year Adams rebounded to 14-14, but in 1916 he developed a sore shoulder and started off the season with a 2-9 record. On August 3 the Pirates released him to St. Joseph, Missouri, of the Class A Western League. He decided not to report.

When his shoulder gained strength over the winter, Adams reported to St. Joseph and put together a stellar 1917 season, going 20-13 with a 1.75 ERA and just 34 walks in 308 innings. The team moved to Hutchinson, Kansas, in mid-season. Hutchinson transferred Babe’s contract to Kansas City of the American Association for the 1918 campaign, but players like Adams who were exempt from the military draft because they were over age 35 suddenly became attractive to major league clubs. Babe re-joined the Pirates and made three late-season appearances.

The Babe Adams of old had returned, his control even better than before his shoulder injury. Despite being the NL’s oldest pitcher in 1920, he led the league in shutouts and allowed just 18 walks in 263 innings, the fewest ever for a pitcher with more than 250 innings. During Babe Adams Day at Forbes Field in June 1923, Babe sounded a little like Satchel Paige: “I cannot explain my lasting much longer than many other pitchers on any other theory than this: I always take things easy, and I never worry.” At age 43 he was still effective enough to toss a shutout inning in the 1925 World Series. Adams remained with the Pirates through August 1926, finally being waived out of the league with a career record of 194-140 and a 2.76 ERA. He dabbled one more season in the minors, then returned to his farm in Mount Moriah in 1928.

A failed Florida land deal and the Great Depression took their toll on Adams’ finances. He continued to farm and in the 1930s became a newspaper reporter, covering local sports. Each time Adams returned to Mount Moriah, and locals remember him as an old man with a cigar, drinking beer at the local joint or sitting on a bench at the Farmer’s Exchange. He was still an athlete—a deadeye quail shooter and an outstanding horseshoe pitcher. In 1958 Babe and Blanche moved to Silver Spring, Maryland, to live with a daughter. Babe died there at age 86 after a long illness. His ashes were returned for burial in Mount Moriah, where the citizens have erected a black marble monument in his honor on the town square. In 2002 the Missouri General Assembly designated a portion of U.S. 136 near Mount Moriah as the Babe Adams Highway.

Note: A slightly different version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

Charles Benjamin Adams

Born

May 18, 1882 at Tipton, IN (USA)

Died

July 27, 1968 at Silver Spring, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.