Bill Caudill

Hard-throwing Bill Caudill pitched in the majors from 1979 through 1987. The righty struck out a batter per inning at a time when that was much less common. “Caudill doesn’t have much finesse,” said The Scouting Report annual for 1983, the year after he emerged as a closer with the Seattle Mariners. “He throws a fastball that is consistently in the 90s. He’ll challenge anybody, and when his ball is up and moving, he can get anybody out.”1

Hard-throwing Bill Caudill pitched in the majors from 1979 through 1987. The righty struck out a batter per inning at a time when that was much less common. “Caudill doesn’t have much finesse,” said The Scouting Report annual for 1983, the year after he emerged as a closer with the Seattle Mariners. “He throws a fastball that is consistently in the 90s. He’ll challenge anybody, and when his ball is up and moving, he can get anybody out.”1

Caudill had one more really good year (1984) before shoulder problems curbed his effectiveness. But he is also memorable for his zany character – something in short supply in the game today. He was one of the top pranksters in the big leagues. Kindred spirits include Jay Johnstone, Moe Drabowsky, and Roger McDowell.

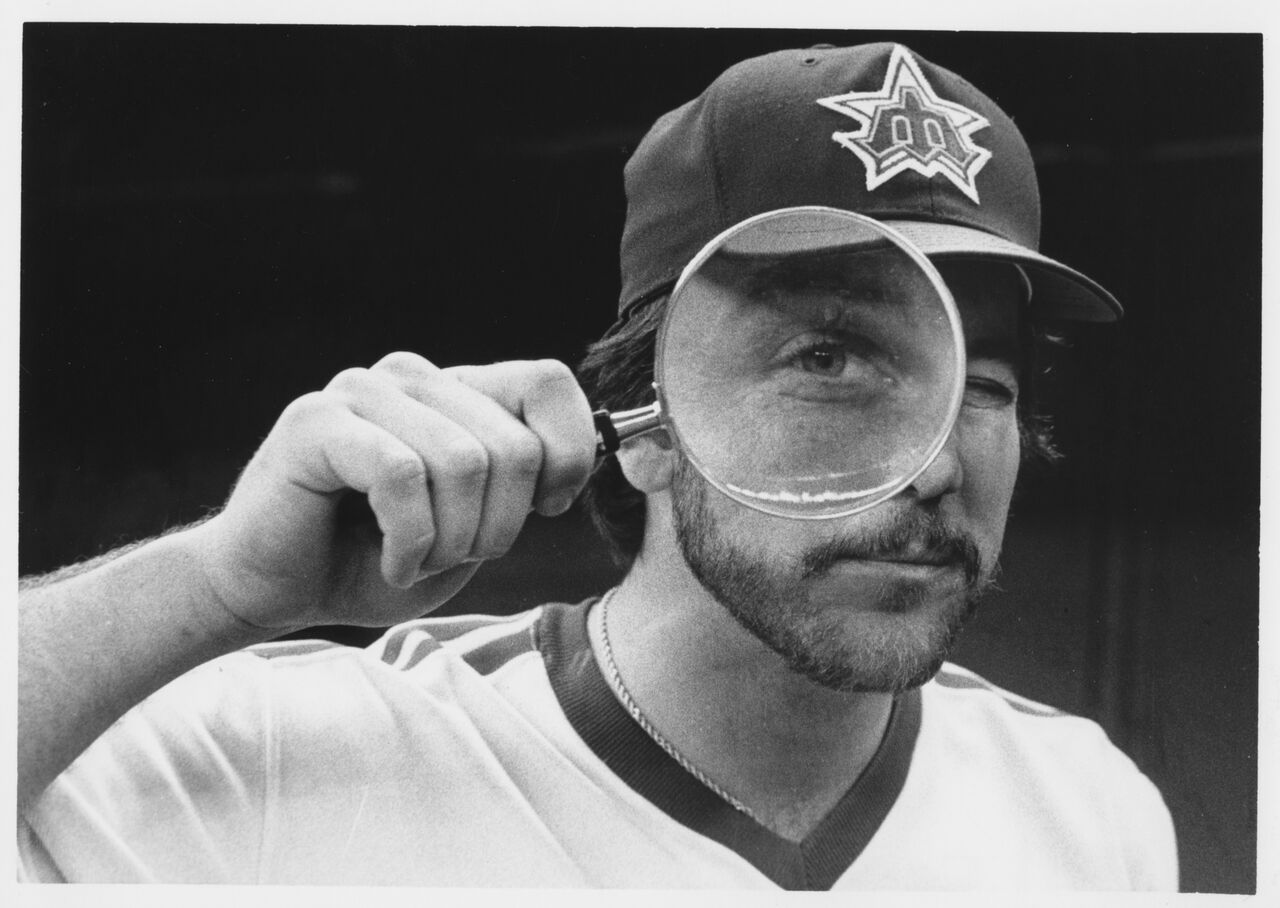

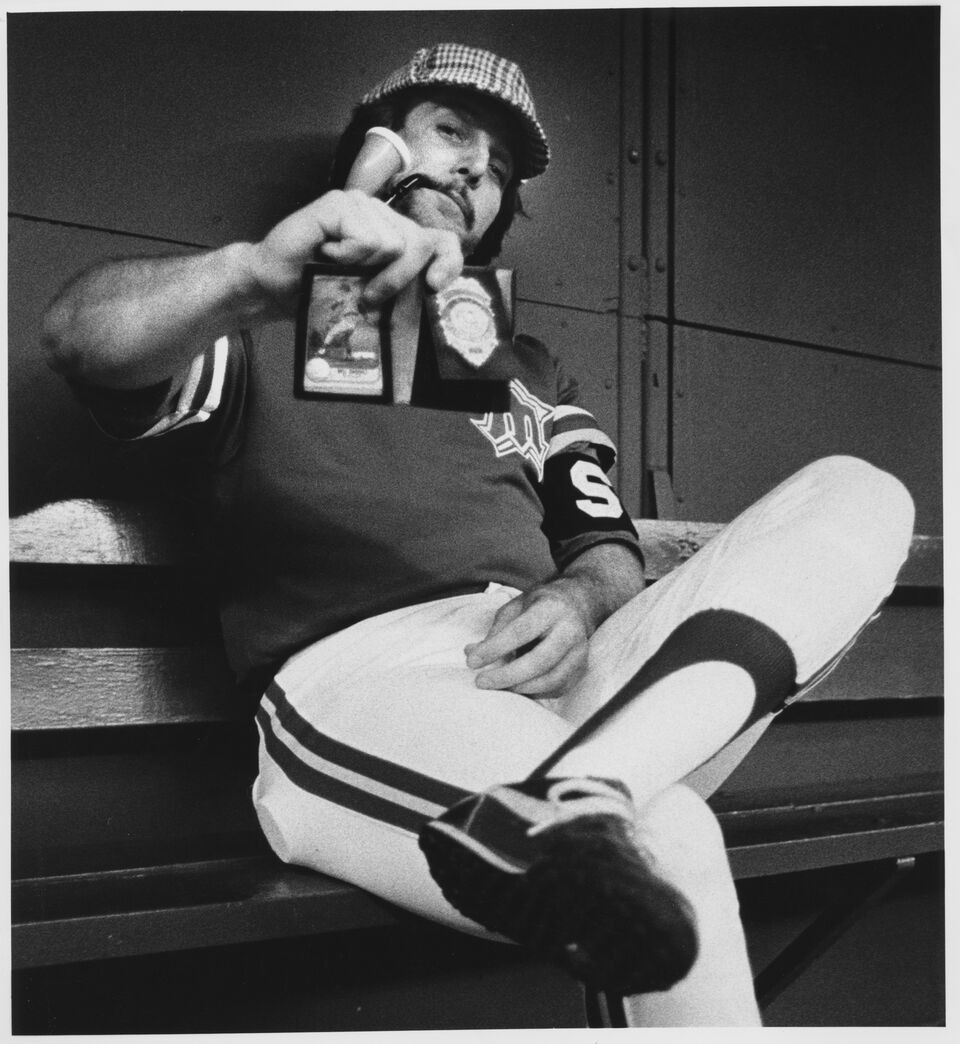

Again in contrast to the current era, when inspired nicknames have largely disappeared from baseball, Caudill had not one but two: “Cuffs” and “The Inspector.” Both reflected his antics. “You’ve got to have fun in order to win,” said Caudill, who took his role as one of baseball’s biggest flakes to heart.2 He had a great time in his deerstalker hat, scrutinizing suspect bats and detaining unwitting victims. The organist at Seattle’s Kingdome, Dick Kimball, played “The Pink Panther Theme” as Caudill’s entry music, in a nod to “Inspector Clouseau” from the movie series.3

Also noteworthy: Caudill was one of super-agent Scott Boras’ first two clients. They became friends as teammates in the St. Louis Cardinals organization in 1974 and 1975, and Caudill later worked for the Boras Corporation as a scout.4

William Holland Caudill – the family name is pronounced “coddle” – was born on July 13, 1956, in Santa Monica, California. His father was Watson William Caudill, also known as Bill. The elder Bill Caudill and his wife, Sharon (née Wolf) had three children: James, Kathleen, and finally the younger Bill, whose middle name came from his grandfather, J. Holland Caudill.

Caudill’s father worked for General Telephone Co. for 18 years and for 21 years in the card-room casino business in Gardena, California. He was very active in Little League and Pony League baseball in Manhattan Beach, another town in the South Bay area. He also influenced his son in another way: “You could also count on [the elder] Bill to tell you a funny story or joke.”5

Young Bill Caudill attended Aviation High School in Redondo Beach, also in the South Bay. When he was still just 17, the Cardinals made him their eighth-round selection in the June 1974 amateur draft. The scout was Bob Harrison.6 Caudill’s first assignment was the Gulf Coast Rookie League, and he made a good first impression, moving up to the Florida State League (Class A) in 1975. He started 25 games that year, completed 12, and threw five shutouts in compiling a strong record of 14-8 with a 3.15 ERA. He struck out 153 batters in 163 innings but walked 87.

Yet after climbing to Class AA in 1976, the prospect endured a difficult year (6-15, 4.44 in 27 starts). His strikeout rate was still high – 140 in 140 innings – but his control, which had diminished in 1975, grew worse (5.8 walks per nine innings). Nonetheless, the Cardinals added him to their 40-man roster that fall.

On March 28, 1977, St. Louis traded Caudill to the Cincinnati Reds for Joel Youngblood, a utilityman for the World Series champions of 1976. Cincinnati sought young pitching, but looking back in 1979, Caudill said, “The Reds wanted me to prove myself all over again. Since they traded for me, I expected to at least move to Triple-A ball. But I didn’t.”7 In view of his 1976 performance, though, it wasn’t really a surprise. With Trois-Rivières in the Eastern League, he remained wild – 72 walks in 114 innings – and his strikeout rate fell off, with just 93 Ks. Even so, The Sporting News observed that July that the Cardinals organization might have let a prize prospect get away. Caudill himself said, “This is my best start ever.”8

After going 13-4, Caudill was promoted to Triple-A Indianapolis. On August 4, he showed his promise by firing a one-hitter against Iowa. He needed just 99 pitches – of which only four were curveballs – to dispose of the Oaks. He made one mistake, in the fourth inning, when he hung the second of two successive curves to Tom Spencer and it became a fly ball that carried just far enough to be a homer.9

Caudill’s control remained shaky, though: he issued 31 walks in 44 innings with the Indians. Still, that September the big club called him up – but he did not appear in any games for the Reds. He had to wait for well over a year to make his big-league debut.

On October 31, the Reds traded Caudill, along with 37-year-old lefty Woodie Fryman, to the Chicago Cubs for another pitcher, 29-year-old Bill Bonham. The Sporting News article about the deal actually focused on the prospect, not the two veterans, saying, “Caudill Seen as Gem in Cub Future.” Chicago’s general manager, Bob Kennedy, director of player personnel for the Cardinals when Caudill first signed, said, “I had him when he was a baby.”10

Wildness still plagued Caudill with Triple-A Wichita in 1978. He walked 105 men in 158 innings, fueling a record of 8-9, 5.53. For the first time since rookie ball, he was used occasionally in relief.

At age 22 in 1979, Caudill finally improved his command. He walked 17 in 36 innings, which still wasn’t outstanding – but in May, with a record of 3-1, 2.75 for the Aeros, he was called up to the majors. He did not pitch minor-league ball again until his final pro season in 1987.

As a rookie for the Cubs, Caudill was 1-7 with a 4.80 ERA in 29 games, of which 12 were starts. He struck out 104 men in 90 innings, which was impressive – but he walked 41 and gave up an alarming 16 homers. A bright spot came on September 29 at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium: Caudill’s first win in the majors. He pitched the last 3 1/3 innings as the Cubs beat the Pirates 6-5 in the heat of the pennant race. With the winning run on base, he struck out dangerous vet Willie Stargell (co-MVP in the NL that year) to end it.

Caudill, who said he’d gained patience and determination, then sought to refine his craft while pitching winter ball in Puerto Rico. He wanted to work in particular on breaking balls, noting that most of the homers he’d given up in 1979 came on hanging curves.11 His numbers with the Santurce Cangrejeros were good: serving mainly as a starter, he was 6-2, 2.34, with 49 strikeouts in 65 innings.12

With the Puerto Rican league as a launching pad, Caudill had a strong 1980 season. He appeared in a career-high 72 games, starting just twice. Although the Cubs finished last in the National League East, their bullpen – which also featured Bruce Sutter, Dick Tidrow, Willie Hernández, and September callup Lee Smith – wasn’t the reason. Caudill logged 127 2/3 innings in relief, striking out 112 and posting a 2.19 ERA.

The Cubs traded Sutter in December 1980, and Caudill could have been a candidate to replace him. He didn’t get the chance and slid back in 1981: 1-5, 5.83 in 30 games. Lee Elia, who became the Cubs manager that October, noted both Caudill’s good arm and love of nightlife. Allegedly Caudill couldn’t adapt to day games at Wrigley Field, though his stats were actually somewhat worse on the road that year. Caudill said, however, that he’d reported for camp in 1981 at 175 pounds – 20 beneath his normal weight – and lost two feet off his fastball. Also, in late April, the Cubs put him back in the rotation, and he made 10 straight starts. With one exception, they did not go well: they were his last in the majors. Being underweight, stretching out was even less advisable. Caudill said that his arm wasn’t ready for it; within three starts, he had lost everything – velocity, control, strength – and was disrupted mentally.13

Several days after he went back to the bullpen, the major-league players went on strike. After play resumed in August, Caudill made 15 patchy appearances that actually fattened his ERA. A personal low point came in a game against San Francisco on August 23 at Wrigley in which he gave up two homers in one inning plus one batter. He nearly quit baseball after manager Joey Amalfitano chewed him out. Dick Tidrow, his mentor, talked Caudill out of it.14

“They tried to discipline me in ways that took my confidence away,” Caudill remembered. I was just a scared human being wondering where I belonged. I pitched only when it was a necessity because I was the last pitcher on the staff.”15

During that dreary year, however, Caudill helped launch the career of Scott Boras. His first agent never had time for Caudill because he was too busy with the veterans. When Boras called to say that he wanted to get started as an agent, Caudill hired him on the spot because he knew that Boras was honest and trustworthy. Trust had become imperative to Caudill, whose parents had divorced when he was young. He remembered that after turning pro, his signing bonus mysteriously disappeared within his family.16

Caudill pitched in Venezuela in the winter of 1981-82, with less success than in Puerto Rico (2-3, 5.93 in seven games for Navegantes de Magallanes). However, he got his weight back up to normal, and as he recalled, Cubs general manager Dallas Green told him that if he pitched decently in spring training, he’d go north with the club.17

Instead, on April 1, the Cubs sent Caudill to the New York Yankees to complete a deal made the previous August, in which Pat Tabler went to Chicago. Just 22 minutes later, the Yankees turned around and dealt Caudill, Gene Nelson, and a player to be named later (Bobby Brown) to Seattle for Shane Rawley. New York also gave Seattle $160,000 to pay off the contract of Dick Drago, whose career ended.18

Caudill had backers in the Mariners organization. Bob Harrison, who’d originally found him for the Cardinals, had become a superscout for Seattle. In addition, manager René Lachemann had seen Caudill pitch in Puerto Rico and also remembered how he’d thrown the ball by Willie Stargell in 1979.19 The skipper said he wanted Caudill to be “the guy who comes in and shuts the door.” Caudill himself said, “It’s an important role and it’s scary. Now, I’m the one who is going to go out and have to do the job.”20

He lived up to those hopes – his best season in the majors ensued. In 70 games, he saved 26, a club record that lasted until Mike Schooler posted 33 in 1989.21 He was 12-9 with a 2.35 ERA and struck out 111 batters in 95 2/3 innings. He was insulted when American League President Lee MacPhail and manager Billy Martin did not name him to the All-Star team (established veterans Rollie Fingers and Goose Gossage were picked instead).

That August, Caudill was the subject of an entertaining feature in Sports Illustrated, entitled “Need Help? Call The Inspector.” The main focus was how much fun Caudill and the Mariners were having under René Lachemann, something that had been missing in Chicago. From a baseball standpoint, though, the key theme was how well he was pitching. As Lachemann said, “I’ve had players on my team as goofy as Caudill. . .but none that were also as important to the team.” The movement on his fastball – running in, out, and up – was overwhelming. Catcher Rick Sweet said, “When he’s got his good velocity, there are maybe 10 hitters in the big leagues that can hit that high one.”22

That August, Caudill was the subject of an entertaining feature in Sports Illustrated, entitled “Need Help? Call The Inspector.” The main focus was how much fun Caudill and the Mariners were having under René Lachemann, something that had been missing in Chicago. From a baseball standpoint, though, the key theme was how well he was pitching. As Lachemann said, “I’ve had players on my team as goofy as Caudill. . .but none that were also as important to the team.” The movement on his fastball – running in, out, and up – was overwhelming. Catcher Rick Sweet said, “When he’s got his good velocity, there are maybe 10 hitters in the big leagues that can hit that high one.”22

Caudill earned both of his nicknames in 1982. He was dubbed The Inspector after the Mariners went 2-7 on their first road trip. “‘It could have been 7-2 if we’d had some timely hitting,’ said Caudill. . .who put on his Sherlock Holmes cap and inspected the bat rack for the missing hits. He would pull out a bat, check its grain, feel its balance, thump it like a watermelon, then throw it away.” Caudill acquired an array of related gear, including magnifying glasses, a genuine customs inspector’s badge, a cape, a calabash pipe, and stuffed Pink Panthers.23

“Cuffs” came from an incident with hotel security guards in the wee hours on the road in Cleveland. Car thieves had been victimizing the parking lot, and Caudill fit the description of the thief. The guards questioned him, and when Caudill didn’t identify himself, they handcuffed him. Teammate Richie Zisk then bought Caudill his own pair of cuffs, with the result that many people – players, clubhouse personnel, and Lachemann’s 13-year-old son Britt – “found themselves handcuffed in bizarre locations for a variety of offenses.” Even Julia Argyros, wife of team owner George Argyros, wasn’t safe.24

One time Caudill got Lachemann to summon him from the bullpen by holding up his wrists as if they were handcuffed – but he blew the save, and the “cuffs” sign went on the back burner.25

The Sports Illustrated article also covered plenty of Caudill’s other pranks in detail. He said, “The only word in pranksterism is originality. I want to pull pranks that people will talk about for 10 or 12 years.”26 Indeed, one of them was still talked about after 30 years. It happened on Opening Night in 1982, when Seattle had a new promotion, the Mariners Fireboat, a bullpen cart in the guise of a vessel that worked the harbor in Puget Sound. The first pitch of the season was about to be thrown when the umpire noticed that the “boat” was still on the left field line. Nobody could drive it off – until Caudill, who had stolen the keys, handed them over. The Fireboat didn’t last long; Gaylord Perry said, “I’ll be damned if anybody’s going to come in and pitch for me riding a tugboat.” He instituted a “kangaroo court” fine of $100 for any reliever who used it.27

According to the Sports Illustrated piece, Caudill and his fellow quirky M’s reliever, Larry Andersen, also invented “rally caps” in a game against Boston on May 30. Trailing 1-0 in the bottom of the ninth, Seattle scored two runs to win after the pen men turned their hats inside out. However, this baseball tradition dates back to at least 1976.28

Heading into the 1983 season, Caudill and tightfisted George Argyros avoided salary arbitration by settling on a one-year deal laden with incentives. One was related to keeping weight down, an ongoing issue for Caudill. He’d been known as “Fat Man” with the Cubs, and “Blimpy” was what got Britt Lachemann cuffed to a Nautilus machine. “It was a way to get George to open up on a contract,” Caudill said in an article devoted to Fat Clauses. He joked, “I just can’t go to bed hungry, heaven knows. I’ll wake up in the morning with feathers in my mouth, having eaten my pillow.”29

That piece also mentioned that Caudill had gotten married that winter. Texas-born Diana Bowser, the new Mrs. Caudill, had worked as a flight attendant for American Airlines.

The Inspector took his act to a new level that April after the team had lost eight of nine games while scoring little. He, Zisk, and Mike Stanton burned 15 bats in a pile outside their clubhouse door. “We pulled one bat out of the fire, crushed the ashes and sprinkled them around home plate and on our bench,” Caudill said. After the ritual, the Mariners scored four runs in the first inning of their next game.30

Although Caudill matched his 1982 save total in 1983, it was an inconsistent year. He was 2-8 with a 4.71 ERA. Mariners beat writer Tracy Ringolsby said that Caudill learned he couldn’t simply show up at the park at his own discretion and get ready in his own way. Caudill also talked frankly about “toning down his postgame activities.” He said, “It used to be after a game, if things went well, I wanted to celebrate – and if they went bad, I’d try to forget.”31

Following that off-year, the Mariners traded Caudill and Darrel Akerfelds to their divisional rival, the Oakland A’s. In return they received reliever Dave Beard and catcher Bob Kearney, a defensive catcher. Beard was gone after one poor season. Kearney stuck around through 1987, playing less and less each year.

A’s president Roy Eisenhardt and manager Steve Boros were elated to have a bullpen stopper, which the team had been lacking ever since losing Rollie Fingers.32 Indeed, Caudill returned to form in 1984: 9-7, 2.71 in 68 games. His 36 saves were a career high, and again he set a club record; this one was surpassed by Dennis Eckersley in 1988. That year he was named to the All-Star Game roster for the only time in his career. He struck out the side in his only inning.

Caudill took a somewhat more serious tack that year. “The Inspector has retired,” he announced that August. He still enjoyed gags, though, like placing doll furniture in the locker of 5-foot-7 teammate Joe Morgan.33

Yet despite his good performance, Oakland traded Caudill that December to the Toronto Blue Jays for Dave Collins, Alfredo Griffin, and cash. Toronto had been seeking bullpen help, but money was another issue. The New York Times wrote that the Blue Jays had found the relief pitcher they wanted, but wondered whether Caudill would be with them for more than one season. Scott Boras said, “They really haven’t come close to making an offer that’s near the recent free agent trend.” Caudill filed for arbitration.34

Just minutes before his hearing began on February 20, Caudill and the Jays agreed to a five-year contract worth at least $1.3 million per season – though Boras and his team viewed $8.7 million as an accurate total figure. At the time it was one of the biggest deals in baseball history. Boras bolstered the pact’s value by negotiating rights for Caudill to appear in team uniform for endorsements, which was something new.35 It was also notable that various stories then referred to the agent, not yet famous, as “Steve.” A few days after the signing, the Sacramento Bee ran a feature detailing the nerve-wracking negotiations with Toronto executives Pat Gillick and Paul Beeston.36

Caudill teamed with another newcomer, lefty Gary Lavelle, in the Blue Jays bullpen. On the surface, he had a solid first year in Toronto: 4-6, 2.99 with 14 saves in 67 appearances. He was doing well in the early part of the season and giving a psychological lift to the whole bullpen. And he was doing it with just one pitch, his fastball. “I throw about one curve a week,” Caudill said early that June. That article called his approach on the mound “about as subtle as a sledgehammer.”37

Soon thereafter, though, that hammer was taken away. Caudill got a viral infection that had a severe side effect: arthritis in his shoulder.38 In early July, one story sniped, “The scuttlebutt in Toronto is that Caudill’s fastball couldn’t get through customs. It was left at the border.”39

Consequently, later that month Toronto turned to Tom Henke as the closer. The Jays finished first in the AL East that year, but Caudill did not appear in any of the seven games in the Championship Series against the Kansas City Royals. Lavelle, whose tender elbow wound up requiring surgery the next year, faced just one batter. Nonetheless, manager Bobby Cox later cited the positive feeling and frame of mind that Caudill and Lavelle had established.40

After the Jays lost the ALCS, however, Caudill didn’t think he’d be back with Toronto. “I’m not a crybaby,” he said. “I’m not one for making excuses and I’m not the kind of guy who can be happy with all his money while sitting back and watching. If somebody had told me I could give back half the money and pitch, I’d probably have done it.” He was happy to have been part of the club and appreciated his teammates’ support, but his diminished role ate at him. He said, “Mentally, I felt like I had about six brain tumors this year.”41

Caudill had the joy of welcoming his first child, Cory, in August 1986. On the field, however, things had gone from frustration to misery. He began the season on the disabled list after his shoulder bothered him in spring training. Upon his return, manager Jimy Williams used Caudill only in mop-up situations, and there was talk of buying out his contract.42 He pitched in just 40 games all year, going 2-4, 6.19. That was despite the best efforts of Scott Boras, who pulled a promotional stunt. An airplane passed over Toronto’s Exhibition Stadium on June 25 carrying a banner: JIMY – GIVE CAUDILL THE BALL.43

Williams said that Caudill would have to pitch well in spring training to make the team in 1987. It didn’t happen, despite Caudill’s optimism about the new forkball that he was using. (The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers observed that he “never really did develop anything like a reliable off-speed pitch.”) The Blue Jays released him on April 1, eating $3.3 million.44

Oakland gave Caudill a tryout, courtesy of the team’s new pitching coach – Dave Duncan, who knew him from holding that role with Seattle in 1982.45 The A’s signed Caudill at the end of that month and assigned him to Triple-A Tacoma.

Caudill was called up in July after Curt Young went on the disabled list. He appeared in his last six big-league games that month, allowing eight earned runs in eight innings. Four of those came in two-thirds of an inning against the California Angels on July 28 – Caudill’s final outing in the majors. He didn’t get a chance to go out on a higher note because on July 31, he broke a knuckle on the little finger of his pitching hand. It happened as he came to his wife’s defense in the parking lot of the Hyatt Hotel in Oakland. They were confronted by a man who’d had too much to drink and had been bounced from the hotel bar.46 Although Caudill came off the DL on September 1, he did not see action during the remainder of the season.47

Caudill chose free agency after the 1987 season rather than accept an outright assignment to the minors. He signed with the Cleveland Indians in February 1988.48 Cleveland wanted him to go down to Class AAA, but he chose family life instead. A few years later he and Diana had a second son, Collin. The couple made their home permanently in the Seattle area after Bill was traded to the Mariners. “We fell in love with the people and the scenery,” he said. 49

A few years after retiring, Caudill talked about how Scott Boras had established a sound financial plan for him and his family. In the knowledge that his baseball career was finite, he saved 75 cents out of every dollar he made. That frugal approach was in effect even before signing the big contract with Toronto. Diana Caudill recalled that it was frustrating to heed Boras’ advice to “live like you’re only making $35,000” – but she also thanked the agent for helping keep her marriage together. She said that when Caudill was in baseball, that was his life, and that there wasn’t a place for women in the game. She couldn’t understand it, but Boras was always there to hear her side of things.50

After quitting as a player, Caudill coached youth baseball with teams from Woodinville and Mercer Island. Family life trumped opportunities to coach professionally. From around 2000 to 2008, he also served as coach of the Eastside Catholic High School baseball team. Another former Mariner, Julio Cruz, was co-coach for much of that time.51

Starting around 2002, Caudill also began to travel extensively and scout potential clients for Boras. In this role, he also helped young pitchers such as Lance McCullers Jr., son of former big-leaguer Lance McCullers. After the younger McCullers made the majors himself in 2015, he credited Caudill’s ongoing advice in navigating minor-league life.52

Throughout the 2012 season, the Mariners celebrated their 35th year as a franchise. To open a homestand on August 13, they invited Caudill to throw out the first pitch, and he flashed his usual impish grin. In an age where “creeping corporate conformity”53 has leached much of the spirit of fun out of baseball, The Inspector reminds fans of what it used to be like.

Last revised: June 24, 2017

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Special thanks to the Seattle Mariners organization: Rebecca Hale (Director of Public Information) and Ben VanHouten (Team Photographer).

Sources

www.californiabirthindex.org

www.caudill.org

www.pelotabinaria.com (Venezuelan statistics)

Diana Caudill profile, LinkedIn.com

www.maxpreps.com

Notes

1 Marybeth Sullivan, editor, The Scouting Report, 1983, New York, HarperCollins: 1983, 295.

2 Tom Green, “Fun-loving Mariners Enjoy Best Season,” United Press International, June 19, 1982.

3 “Bill Caudill: The Inspector Returns to the Scene,” From the Corner of Edgar & Dave (a Seattle Mariners blog), August 10, 2012.

4 The other initial Boras client, Mike Fischlin, grew up with the agent in Elk Grove, California, and also went on to work for Boras Corp.

5 “Watson W. (Bill) Caudill,” The Olympian (Olympia, Washington), April 10, 2002.

6 E.M. Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector,” Sports Illustrated, August 16, 1982. (https://www.si.com/vault/1982/08/16/625670/need-help-call-the-inspector)

7 Andy Knott, “Caudill gives thanks to Kingman, Reds,” Chicago Tribune, July 24, 1979, 47.

8 “Eastern League,” The Sporting News, July 23, 1977, 60.

9 “A.A. Atoms,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1977, 40.

10 Richard Dozer, “Caudill Seen as Gem in Cub Future,” The Sporting News, November 19, 1977, 48.

11 Joe Goddard, “Caudill Heating Up for Big Cub Summer,” The Sporting News, January 19, 1980, 38.

12 Thomas Van Hyning, The Santurce Crabbers, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1999, 215.

13 Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.” Robert Markus, “Jays’ Caudill Also Relieves Tension,” Chicago Tribune, June 2, 1985.

14 Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.”

15 Markus, “Jays’ Caudill Also Relieves Tension.”

16 San Diego Union-Tribune, April 1, 1992. The title of this article is not presently available. Excerpts were presented in “How Scott Boras Became a Baseball Super-Agent,” Misc. Baseball blog, December 4, 2010. The name of Caudill’s first agent has not yet surfaced. Dan Raley, “Where Are They Now: Bill Caudill, Mariners Reliever,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 17, 2005.

17 Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.”

18 Tracy Ringolsby, “M’s Want Caudill to Shut the Door,” The Sporting News, April 24, 1982, 35.

19 Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.”

20 Ringolsby, “M’s Want Caudill to Shut the Door.”

21 Caudill, by then retired, was at the Kingdome to see Schooler pick up #27 on September 11, 1989. “Mariners,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1989, 15.

22 Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.”

23 Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.”

24 Raley, “Where Are They Now: Bill Caudill, Mariners Reliever.” Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.” Michael Emmerich, 100 Things Mariners Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die, Chicago, Illinois: Triump Books LLC, 2015: 170.

25 Kirby Arnold, Tales from the Mariners Dugout, New York: Sports Publishing, 2007. Lachemann recalled that Caudill gave up a three-run hmer, but his memory appears to have been a little hazy. The closest actual incident came on June 18, 1982, when Caudill gave up a pair of two-run homers in the ninth inning as Seattle lost to Kansas City, 4-1.

26 Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.”

27 “Bill Caudill: The Inspector Returns to the Scene.” Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.”

28 Swift, “Need Help? Call the Inspector.” The Chattanooga Lookouts of the Southern League did it in 1976. “Turn Caps for Rally,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1976. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary states that it came to the major leagues with the Texas Rangers in 1977-79.

29 John Nelson, “ ‘Crash diets’ become ‘cash diets’ in baseball,” Associated Press, March 20, 1983.

30 Herm Weiskopf, “Inside Pitch,” Sports Illustrated, May 9, 1983.

31 Tracy Ringolsby, The Sporting News, August 15, 1983, 23-24. That article appeared while Caudill was out with a sprained ankle.

32 Kit Stier, “A’s Hail Caudill as Bullpen Savior,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1983, 48.

33 Kent Baker, “Caudill helping A’s down the stretch,” The Baltimore Sun, August 16, 1984.

34 Murray Chass, “Dodger Action on Drugs Irks Both Sides,” New York Times, January 27, 1985.

35 Susan Kuczka, “Jays Sign Caudill,” United Press International, February 20, 1985. Tim Dierkes, “Boras Blast from the Past: Bill Caudill,” MLBtraderumors.com, March 26, 2009.

36 Sacramento Bee, February 24, 1985. The title of this article is not presently available either. A long extract was also presented in “How Scott Boras Became a Baseball Super-Agent.”

37 Markus, “Jays’ Caudill Also Relieves Tension.”

38 “Cards get ‘premier’ catcher Pena,” Associated Press, April 2, 1987.

39 Richard L. Shook, “Blue Jays Playing Tough Despite Some Problems,” United Press International, July 6, 1985.

40 Peter Gammons, “How Do You Spell Success? RELIEF,” Sports Illustrated, April 4, 1988.

41 “Blue Jays’ Caudill Unhappy,” Palm Beach Post, October 18, 1985.

42 “Toronto reliver Bill Caudill is fed up with pitching,” United Press International, June 14, 1986.

43 “Between the Lines,” Sports Illustrated, July 7, 1986.

44 “Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, March 2, 1987, 27. “Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1987, 35. Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers, New York: Fireside, 2004: 160. “Blue Jays,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1987, 19.

45 “Athletics,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1987, 17.

46 Kit Stier, “A’s Miffed Over Davis Injury, But Back Up Caudill,” The Sporting News, August 17, 1987.

47 “Athletics,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1987, 17.

48 “Athletics,” The Sporting News, January 4, 1988, 60. “Indians,” The Sporting News, February 22, 1988, 39.

49 Raley, “Where Are They Now: Bill Caudill, Mariners Reliever.”

50 “Ex-Reliever Caudill Gets The Save,” Seattle Times, May 12, 1991. San Diego Union Tribune, op. cit.

51 Raley, “Where Are They Now: Bill Caudill, Mariners Reliever.” “Ex-M’s Infielder Julio Cruz To Coach Baseball Team At Eastside Catholic,” Seattle Times, December 11, 1999. Danny O’Neil, “Package deal,” Seattle Times, April 18, 2000.

52 Raley, “Where Are They Now: Bill Caudill, Mariners Reliever.” Marc Nemcik, 2012 MLB Draft Q&A: Lance McCullers,” Scout.com, April 25, 2012. Evan Drellich, “McCullers’ rise as a starter a relief to Astros,” Houston Chronicle, June 6, 2015.

53 Charles P. Pierce, “The Last Great Flake,” Slate.com, May 28, 2003. The subject of this article was Roger Clemens.

Full Name

William Holland Caudill

Born

July 13, 1956 at Santa Monica, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.