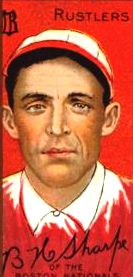

Bud Sharpe

Popular wherever he played, Bud Sharpe showed great promise on the field and later as a manager, only to die in his prime. A tall and energetic man, the slender Sharpe stood 6′ 1″ and weighed 170 pounds. A right-hander, he was a minor figure in his 165-game major league career, posting a .222 average in two seasons (1905, 1910), while playing all but four of his games with the Boston Nationals. His six-year, 761-game minor league career was more successful; two pennants, a .264 average and a perennial fielding leader at first base. The Oakland Tribune called him “a perfect wonder at the bag… as a player he has a fast, dashing style which always draws the fans.”

A combination of athletic ability, intellect, and modesty, Bud Sharpe made significant contributions outside of baseball, in part-time careers as an electrical engineer and a college instructor. When illness ended his playing career, Sharpe became a manager, leading the Pacific Coast League’s Oakland Oaks to their first pennant in 1912. Of this triumph, the Oakland Tribune said “Temperamentally, he was an ideal leader; firm, but not too strict, quick to encourage and to inspire and yet capable of giving a negligent player a dressing down that would have its effect.” In his hometown obituary, the Daily Local News was certain that “had he been able to retain his health, [he] would doubtless have become a manager equal to the best in America.”

A native of West Chester, Pennsylvania, Bayard Heston Sharpe was born on August 6, 1881, to Howard W. and Elizabeth (Carey) Sharpe. His father, a bricklayer, was a contractor who, according to the Los Angeles Times, “created some of the largest institutions in the Keystone State, among which are the State Normal School at West Chester [now West Chester University].” Also a sportsman, the elder Sharpe was a member of the West Chester Hunt Club.

Bayard’s mother, called “Lizzie,” was from “one of the largest and most honored of the families in the county.” The Sharpes also had a daughter, Edith, who died at age 16 from tuberculosis. Lizzie was fond of calling Bayard “my little rosebud,” so he became “Bud.”

Unfortunately for the Sharpes, Lizzie died in 1890 at age 30. Two years later, Howard married Maggie Cope, providing Bud and Edith with a stepmother.

Bud didn’t crawl like most infants. When others his age were scooting on hands and knees, he startled his family by running down the hallway and sliding through the parlor door and under the sofa, executing the last maneuver with what the Los Angeles Times later called a “perfect ‘hook slide.” Thereafter, it was a foregone conclusion that he would be a baseball player. Athletic ability wasn’t his only talent. By age eight, he was studying the piano. He was an expert by age 12, and by the time he was 14 he had sung for four years in the Holy Trinity Church choir.

Bud Sharpe received his education in the public schools of West Chester and graduated with honors from West Chester High School in 1899. He played baseball on the junior teams around town before excelling for the high school nine. Sharpe also played basketball and football for the Active Athletic Association.

Bud enrolled at Pennsylvania State College in fall 1899. He played his first collegiate baseball game on April 14, 1900. In a 19-3 demolition of Susquehanna, Sharpe’s debut featured five hits, including a triple, a stolen base, and four runs. He made some pretty plays at shortstop and also pitched, striking out five. A year later, he was team captain, continuing to pitch and play shortstop. His season highlight was a game at West Chester Normal on May 17 where a large crowd gathered with many of his friends in attendance. He entertained them by pitching an 11-4 win and hitting a single, a triple and a home run. Penn State finished the season with an 11-3 record.

Sharpe was Penn State’s leading batter in 1902 with nine hits, including two home runs, two doubles and a triple. The team posted a 6-2 mark. The Nittany Lions were a .500 baseball club in 1903. Bud Sharpe had two hits in at least three of the ten ball games.

A well-rounded student-athlete, Sharpe played on the 1902 Penn State basketball team. He also was a member of the cadet military battalion, sang in a quartet, and had a leading role in a drama production. He graduated from Penn State in May 1903 with a degree in electrical engineering. The college offered him a position as a mathematics instructor, which he rejected in favor of playing baseball.

In the summer of 1900, Bud Sharpe began a five- year semi-professional career with the famed Brandywine baseball club. Founded in 1865, the club numbered among its former members such nineteenth century major leaguers as Doc Bushong, Joe Battin, Jack McMahon, Mike Grady and Joe Borden. On July 28, 1901, after a 6-4 Brandywine victory over the Chester Athletics, the Philadelphia Inquirer said, “Sharpe, the State College athlete, is playing a fast and brilliant game at first base for the Brandywines.”

On August 3, 1902, the Inquirer, calling him “one of the best all-around athletes in State College,” reported that Sharpe “is ill with an attack of typhoid fever.” Three weeks later the Brandywine team played a benefit game for his medical care.

According to the Daily Local News, Bud played professionally for Harrisburg in 1903. He “was in ill health at the time and believed that a year on the diamond would be the best kind of medicine.” Evidence of his time with Harrisburg is lacking; no official statistics were published for the outlaw league, and his name doesn’t appear in any game accounts. He did play again for Brandywine, serving as team captain. In the fall of 1903, Sharpe took a position as mathematics instructor at Bellefonte Academy, 15 miles north of State College.

Bud worked in 1904 as a specialist at West Chester’s Sharpeless Separator Company, the first milk processing plant of its kind in the country, which used a centrifuge to separate the cream from the milk.

Sharpe’s 1904 season with Brandywine was his best ever, attracting many major league offers. The Daily Local News of West Chester said “Sharpe came under the eagle eye of [1904 Boston manager] Al Buckenberger, who enticed him into the fold of the Boston Nationals.” Boston purchased him in early October 1904. Between the 1904 and 1905 ball seasons, Sharpe was an electricity instructor at Pennsylvania State College.

On October 5, 1904, Sharpe married Bertha Elizabeth Thorp, daughter of John and Ida (Wiltbank) Thorp. Miss Thorp was “prominent in musical circles.” The couple would be childless during their twelve-year marriage. John Thorp, a funeral director, was a member of the West Chester borough council and served four terms as chief burgess. Ida Thorp, said to be a direct descendant of William Shakespeare, was active in church and charitable affairs.

Bud Sharpe made his major league debut on April 14, 1905. He was hitless in three at-bats as New York routed Boston 10-1. His first hit came four days later off Brooklyn’s Harry McIntire in Boston’s home opener, a 4-2 win. On May 11, Sharpe showed that he could field in a 5-0 win over Chicago. The Boston Globe said, “Two catches by Sharpe in right were the features of the game, one within a few inches off the ground, and the second after a running jump.”

On June 3, in the first of three appearances at catcher, Sharpe caught Vic Willis, then in the middle of his Hall of Fame career, in an 8-3 home loss to New York. Bud gave up four stolen bases and had two passed balls in the contest, batting 1-for-4. The Globe said, “Until Tom Needham and Pat Moran are in shape again Sharpe will probably catch. He showed yesterday that with a little work he will be all right.”

Except that Sharpe was not all right. By mid-June Sharpe was having difficulty playing the sun in right field. “His showing was far from sensational,” Sporting Life noted. Other reports said Bud encouraged four of his teammates to jump to the Tri-State League, an “outlaw” organization offering good salaries to players from struggling teams.

Manager Fred Tenney wasn’t happy with the reports. Sharpe was promptly released after going hitless in an 11-2 Boston loss in Cincinnati on June 15. He finished his stint with Boston hitting .182 in 46 games. His fielding average in right field was an unimpressive .904.

Other work soon emerged. On July 17, Sharpe, according to the Globe, was “doing good work for Coatesville of the outlaw [Tri-State] league. His specialty seems to be two-base hits every game.” By mid-August, poor attendance doomed Coatesville, causing the franchise to move to the coal town of Shamokin, Pennsylvania. The club finished with a 56-69 record, 22 — games behind Williamsport.

In December 1905, Scranton of the New York State League signed Bud Sharpe to a 1906 contract. Bud played every game for the pennant-winning Miners, posting a .295 average, ninth in the league. He was first in the league with a .990 fielding percentage and his 150 assists were 44 more than his nearest pursuer. In the 1905-1906 off-season, Bud Sharpe continued to work as an electrical engineer, supervising the installation of several large power plants in Pennsylvania.

In mid-April 1907, Bud signed a contract with the Newark of the Eastern League, where he would stay through 1909. As team captain all three years, he played first base and usually batted fifth in the order. On July 16, 1907, Sharpe was seriously injured when he was beaned by a pitched ball from Montreal’s Tom Hughes. Unconscious, with blood running from his mouth and nose, it was first feared that his skull was fractured, but it was soon determined that he was not in immediate danger. It would be a week before Bud saw further action, going hitless as a pinch-hitter in a 10-1 loss against Baltimore. Late in August, Sporting Life said Sharpe “has taken a brace in his hitting since he returned to playing after his accident.” Newark finished with a 67-66 record, tied for fourth place with Jersey City. Sharpe hit .210 in 125 games.

He spent the winter of 1907-1908 as a physics and electricity instructor at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where he also served as baseball coach until season’s end on March 27.

George Stallings, a veteran major and minor league skipper, was Newark’s manager in 1908. For Bud, it was the beginning of an eight-year association with the intense and superstitious Georgian. Newark finished in third place with a 79-58 record, its highest finish in six Eastern League seasons. Sharpe hit .270 and was third in the league with 151 hits. He played a league-leading 146 games and his .989 fielding mark at first base was also tops.

Newark’s post-season barnstorming took them to West Chester on September 25, where a large crowd turned out to see them play Sharpeless Athletic Association. Before the game, Sharpe was presented with a gold purse by friends. Newark won the game 2-1; Sharpe was hitless.

Bud Sharpe was not only adept at baseball, he was also a soccer enthusiast who put together a club in West Chester in the fall of 1908. In February 1909, Bud became the baseball coach at Georgia Military Academy in Milledgeville, Georgia, a position he held until May.

The 1909 Newark manager was Joe McGinnity, who had just concluded his Hall of Fame career with the New York Giants. McGinnity thought Sharpe was “one of the best first basemen in the country.” By June, it was apparent that some major league managers agreed, with the Detroit, Philadelphia, and St. Louis American League clubs leading the pack. Others, however, were skeptical, regarding him as “a great minor league player” and nothing more. Despite the opinions, none of the deals materialized. Bud Sharpe was drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates on September 1 and would report for training in spring 1910.

Prior to a season-ending doubleheader, Umpire Lord Byron called Captain Sharpe to home plate and presented him with an engraved gold watch, a gift from some well-connected fans who wanted to give him a lasting token of their admiration. A Newark newspaper quoted in the Daily Local News said “his deportment here has always been that of a gentleman.” Newark finished the season in second place with an 86-67 record. Bud hit .241 in 156 games and for the third straight year led the league in fielding with a percentage of .994.

During their season together in 1908, Bud Sharpe and George Stallings had become close friends. After the 1909 baseball season, Bud accepted Stallings’ offer to become manager of Stallings’ cotton plantation in Haddock, Georgia. For a few weeks during the winter, Bud and Bertha left Georgia to visit friends and in-laws in West Chester.

Bud reported to the 1910 Pirates’ camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and was in competition with first baseman Jack Flynn. He was also suffering from malarial fever contracted during the winter. Spring workouts didn’t give Manager Fred Clarke a clear-cut choice, so he carried both men on his roster. Sharpe started on Opening Day and was 1-for-4 in a 5-1 win at St. Louis. He made a strong case for the job the next day by going 2-for-4 with a triple and two runs in a 6-5 loss. Hitless the next two games, Sharpe sat while Flynn was given his chance. On April 28, Clarke chose Flynn and traded Bud and pitcher Sam Frock to the Boston Nationals for pitcher Kirby White.

In May the Globe said “Sharpe was a little uncertain on low thrown balls, but looks like a man who will strengthen the infield.” The third batter in the Boston order, he was hitting .271 a month after the trade. By mid-June, Boston had fallen to the basement. The Anaconda Standard said, “Bud Sharpe, a Pittsburg discard, seems to be about as good a first baseman as the man who was retained in preference to him.”

On June 23, a number of West Chester citizens turned up in Philadelphia to watch Bud Sharpe. Before the game three men presented a floral piece to him. In the fourth inning, Sharpe ripped a single, to the delight of his fans. Silence followed when he was thrown out trying to steal second. Boston managed only two more hits on the day and was shut out 4-0.

By early July, Sharpe was hitting .276 in 199 at-bats; Manager Fred Lake had moved him from third to sixth in the batting order. On July 6, he was not able to play due to “a slight attack of malaria.” In mid-month, the Nebraska State Journal said, “Bud Sharpe has amply made good as first baseman for the Doves.”

Bud’s hitting declined the season’s final months as the Boston staggered to a last-place finish. He played his last major league game on September 24 in a 4-2 loss to Cincinnati, going 1-for-3 against George Suggs. Sharpe posted a .239 average in 115 games and fielded .987 at first base.

In February 1911 George Stallings acquired him for the Eastern League’s Buffalo Club, and named him team captain. In April, Sporting Life said “Sharpe predicts that he will be one of the best hitters in the Eastern League this year.” Bud backed his boast by hitting well for two months. Halfway through July, Buffalo was in sixth place. Sporting Life said “Bud Sharpe….may have to leave Buffalo on account of ill health.” Sharpe seemed to recover; on July 28, a 13-8 rout of Newark, the magazine said “Miller’s home run and Sharpe’s two three-base hits were the features.”

Buffalo’s catcher was Bill Killefer, who went to the Philadelphia Phillies at the end of the season and resumed his major league career. Killefer married the younger sister of Bud’s wife Bertha, Margaret Smith Thorp, in 1917. The Sharpes probably introduced them; the Daily Local News once reported that Killefer first visited West Chester in 1911.

Health problems prematurely ended Bud Sharpe’s season in Buffalo. With Buffalo out of the race, Stallings sent him to take charge of his plantation. Buffalo finished the season in fourth place with a 74-75 record. Sharpe appeared in 102 games, hit .281, stole 27 bases, and again led the league in fielding percentage with a .992 mark.

On Monday, November 20, George Stallings awoke to the smell of smoke in his plantation home. Stallings, Sharpe and their wives attempted to quell the blaze, but, according to Sporting Life, “the fire had gained such headway that by the time help arrived the structure was a mass of flames and all had to flee in their night clothes.” The structure and its contents were burnt to the ground, leaving both couples “practically homeless and living in a shack on Mr. Stallings plantation.”

Stallings, who waived Sharpe on November 18, said “Sharpe is not well enough to play all season.” By Christmas, Bud had been hired to manage the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. Stallings endorsed Sharpe, saying “I feel sure that he will prove a success in his new berth.”

Sharpe inherited a club that finished third in 1911. To the Oregonian, the 1912 Oaks “were figured a weak sister by all the experts.” After an Opening Day loss to San Francisco, Oakland took a 3-2 victory the next day. Bud Sharpe was 2-for-4 with a stolen base, but disputed a call at second base and was ejected from the game.

Oakland promptly added twelve consecutive wins; mid-April statistics showed Sharpe hitting .304. The streak ended on April 18 with a 4-2 loss to Los Angeles, but the Oaks were in first place with a 13-2 record. Bud was ejected two more times in the season’s first three weeks, including one on April 21 that earned him a three-day suspension.

Oakland continued to win in May and was in first place because they dominated Portland, winning eight of ten games. In a 7-2 win at Los Angeles on May 2, Bud was 3-for-5 and scored a run. Six days later, he was spiked at Vernon and had to leave the game. He returned on May 17, going 2-for-4 in a 5-0 win at San Francisco.

A 5-4 loss to Sacramento on May 24 dropped Oakland to second. Vernon had taken the lead and would hold it for over three months. On July 16, Oakland was 56-42, three games behind Vernon. Going into the ninth inning at San Francisco, the Oaks were down 1-0 with the bottom of the order coming up. With Al Cook on base, Bud Sharpe pinch-hit and poled a liner to right to score the tying run. A moment later, Tyler Christian scored the winning run on a sacrifice fly.

The Oakland Oaks lost ground to Vernon, sinking to third on August 17. On September 6, the Tribune announced that “Manager Bud Sharpe…. is a sick man, being confined at home with a severe attack of pleurisy…. The long season on the coast worked havoc with his constitution.” The paper speculated that 1912 would be Sharpe’s only season in Oakland.

September 13 found Oakland back in first place, thanks to a 4-1 win over Portland. The Oaks had won 18 of 23 games since August 27, including five of seven from Vernon. The race was now between Oakland, second place Los Angeles, and Vernon.

The pennant race came down to the final day, October 27, with Oakland trailing Vernon by percentage points. Undaunted, the Oaks defeated Los Angeles in a Sunday doubleheader, 5-4 and 6-0, with Bill Malarkey pitching the deciding second game, holding the Angels to two hits. Oakland had won its first PCL pennant with a record of 120-83, four percentage points over Vernon. Third baseman Gus Hetling (.297) was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player. Bud Sharpe hit .300 in 101 games.

On his doctors’ advice, Sharpe immediately resigned as manager. The Tribune said “Sharpe, in none too robust a condition, finally weakened from his exertions and was compelled to keep to his home…. Sharpe’s spirit, though, inspired the club to keep on struggling and eventually nosed out the contenders.” On October 28, the Oakland players presented a jubilant Bud Sharpe with a beautiful diamond cravat pin to show their appreciation of his services.

The Sharpes returned to Georgia and Bud resumed his plantation duties. Located in Jones County, Stallings’ enterprise was seven square miles of villages, churches, and schoolhouses serving a population of African Americans descended from pre-Civil War slaves. The landscape was steeped in history, having been granted to Stallings’ forbears in the mid-1730s. The original colonial mansion, which burned by accident in 1911, had served as a headquarters for Union General George T. Sherman during his 1864 “March to the Sea.” Though Sherman burned the countryside far and wide, he spared the manor house itself.

Stallings, who was now manager of the Boston Braves, used Bud as a scout, mostly in the Southern League, with occasional trips to other parts of the country. In December 1912, Sharpe wrote the Tribune and reported that his health had improved during the winter months.

In mid-March 1913, Sharpe visited Augusta to look over Manager Bill Dahlen‘s Brooklyn Superbas. In early May, reports said that Sharpe was visiting minor league camps looking for outfield talent. Bud took a scouting trip to Oakland in November 1913. He played first base for a team called Boyle and Lawlor in two Oakland Winter League games and performed well, posting five total hits and driving in five runs in the second game.

Of Sharpe’s years in Georgia, the Daily Local News said, “he received visitors from many parts of the country who consulted with him on baseball and other matters, for he had friends from coast to coast. On his occasional visits north he was welcomed as a hero, and admired because of the laurels he had won.”

Bud’s health continued to fluctuate during his last three years. In mid-December 1913, reports said he was seriously ill. Ten months later, Sharpe was reported to be in “perfect health.” In July 1915, the Oakland Tribune described him as “healthy as a young bear…. specialists have told him….that [his condition] is not consumption.”

Sharpe’s physicians were wrong. He died from tuberculosis at age 34 on May 31, 1916, after a six-week illness. Bertha, who had faithfully attended him during all of his illnesses, left the next morning to take his body to West Chester. Sharpe’s funeral was held on Saturday, June 3, and was conducted by his father-in-law, John Thorp. The last surviving member of his family, Bud Sharpe was buried at Greenmount Cemetery next to his parents and sister. Among others, tributes were received from the Boston Nationals, George Stallings and Johnny Evers. Flags at the Oakland ball park flew at half-staff.

George Stallings’ second wife, Eunice (Davis) Stallings, had died after a long illness in Buffalo, New York, on August 29, 1913. On May 7, 1917, Stallings and Bertha Thorp Sharpe were married in West Chester. Their son, George Jr., was born on February 4, 1918 and went on to play baseball at the University of Georgia. George Sr. died on May 13, 1929. Bertha Stallings retained her husband’s interest in the Montreal club of the International League for a number of years. She was 67 when she died at Haddock on January 14, 1952. The Stallings family is buried at Riverside Cemetery in Macon, Georgia.

Sources

West Chester, Past and Present: Centennial Souvenir with Celebration Proceedings. By West Chester (PA) Daily Local News. 1899.

Lane, F. C. “The Miracle Man.” Baseball Magazine Vol. XIV, No. 4 (February 1915): 57-65.

Oakland Tribune, 1912-1916

San Francisco Chronicle, 1912, 1916

Los Angeles Times, 1911

Philadelphia Inquirer, 1896-1916

Penn State Free Lance, 1900-1904

Sporting Life, 1904-1912

Boston Globe, 1905, 1910

Syracuse Herald, 1909

San Jose Mercury News, 1909

Pawtucket Times, 1910

Washington Post, 1910

vAnaconda Standard, 1910

Boston Journal, 1910

Ft. Wayne Sentinel, 1911

Oregonian, 1912-1913

New York Times, 1913

West Chester Daily Local News, 1901-1952

SABR Baseball Encyclopedia

SABR Minor League Database

Baseball-Reference

Wcjim.com

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Diane Rofini, Librarian at the Chester County (PA) Historical Society for the Sharpe clipping file.

Full Name

Bayard Heston Sharpe

Born

August 6, 1881 at West Chester, PA (USA)

Died

May 31, 1916 at Haddock, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.