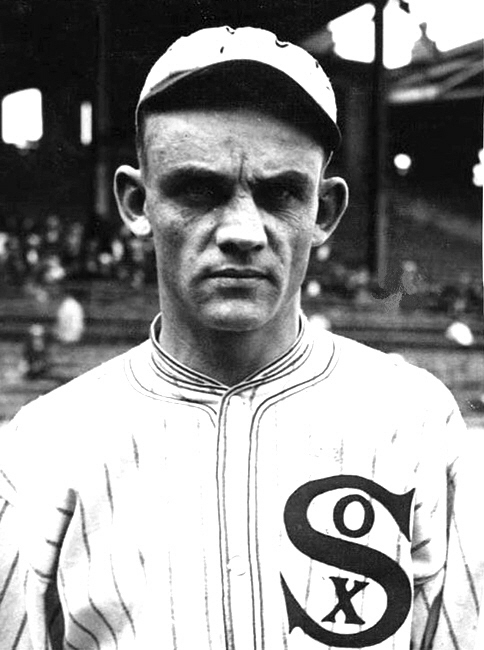

Chick Gandil

Prior to his infamous involvement in the 1919 Black Sox Scandal, Chick Gandil was one of the most highly regarded first basemen in the American League, both for his play on the field and his solid work ethic. In 1916 a Cleveland newspaper described Gandil as “a most likeable player, and one of excellent habits.”1 From 1912 to 1915 the right-handed Gandil starred for the Washington Senators, leading the club in runs batted in three times and batting .293. In the field Gandil paced American League first sackers in fielding percentage four times and in assists three times.

He continued his strong work with the Chicago White Sox from 1917 to 1919, helping the club to two American League pennants before forever tarnishing his legacy by helping to fix the 1919 World Series. Yet Gandil may have been the only banished player who gained more than he lost from the fix. After the 1919 World Series, the first baseman retired from major-league baseball, reportedly taking $35,000 in cash with him.

Arnold Gandil was born on January 19, 1888, in St. Paul, Minnesota, the only child of Christian and Louise Bechel Gandil. After a brief stay in San Francisco in the early 1890s, the family moved to Seattle by the turn of the century and then to Southern California, where Gandil began playing baseball seriously as a teenager. By 1904, when he was 16 years old, Gandil dipped his toes in the amateur baseball ranks. That year he played for a team sponsored by the Los Angeles Herald newspaper, playing many different positions throughout the year.2

In 1906, Gandil left home to play semipro ball in Amarillo, Texas, before that team fell on hard times. He returned to California to make his debut in Organized Baseball that same year, playing two games with Los Angeles and Fresno of the Pacific Coast League.3 In 1907 he had another one-game tryout with Portland of the PCL but spent most of the season in Humboldt, Arizona, as the catcher for a semipro team sponsored by the local copper smelter. He frequently used the alias “Chick Arnold” during this time.4

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

The Humboldt club experienced financial problems, however, and Gandil moved on to a team in Cananea, Mexico, 40 miles from the US border. It was with Cananea that Gandil became a first baseman. In addition to his employment as a baseball player, Gandil worked as a boilermaker in the rugged copper mines. He also did a bit of professional boxing, reportedly receiving $150 per bout.5 The year before Gandil’s arrival, the mine in which he worked had been the site of one of history’s most famous labor battles, with the Mexican Army and Arizona Rangers bloodily suppressing a workers’ uprising at the behest of the American-owned mining company — an incident that many historians consider the first battle of the Mexican Revolution.6

Gandil spent the 1908 season with Shreveport (Louisiana) in the Texas League, batting a solid .269. Off the field, he wed Laurel Kelly, a 17-year-old Mississippi native who went by Faye.7 They had one daughter, Idella, and were married for 62 years.

After the season Chick was drafted by the St. Louis Browns, but failed to make the club the following year. The Browns ordered him back to Shreveport, but Gandil refused to report, instead joining the Fresno team in the outlaw California State League. Faced with being blacklisted by Organized Baseball, Gandil joined Sacramento of the Pacific Coast League for the 1909 season. He was soon arrested for absconding with $225 from the Fresno team coffers,8 but had good success in Sacramento, batting .282. Late in the year he was sold to the Chicago White Sox, but wasn’t required to report until the following season.

Gandil’s rookie season, 1910, was by far the worst of his career. As a part-time performer with the White Sox, he appeared in 77 games, hitting an anemic .193. Reportedly, he had trouble hitting major-league curveballs.9 In mid-September, he and infielder Charlie French were sold by the White Sox to Montreal of the Eastern League, a deal that caused Gandil’s first dispute with owner Charles Comiskey. Since the deal was made within 10 days of the end of the minor-league season, Gandil and French appealed to receive their full major-league pay for the season. But the National Commission ruled against them because they had refused to report to Montreal.10

Gandil spent the offseason back in Shreveport as a policeman11 and then reported to Montreal in the spring. He responded with a solid season, batting .304. In December 1911 Chicago Cubs owner Charles Murphy worked out a deal to acquire Gandil for $5,000 and two players, but two other National League teams blocked the transaction.12 So Gandil returned to Montreal.

Gandil got off to a solid start in 1912, batting .309 in 29 games, after which he was traded to the Washington Senators. This time, the big first sacker was ready for the major leagues, and in 117 games with Washington he hit .305 and led American League first basemen in fielding percentage.

Gandil was highly regarded by Washington. In 1914 Senators manager Clark Griffith wrote, “He proved to be ‘The Missing Link’ needed to round out my infield. We won seventeen straight games after he joined the club, which shows that we must have been strengthened a good bit somewhere. I class Gandil ahead of McInnes [sic] as he has a greater range in scooping up throws to the bag and is just as good a batsman.”13

Gandil continued to perform well with Washington both at bat and in the field. In 1913 he hit for a career-high average of .318. He was also tough and durable, averaging 143 games during his three full seasons with Washington, despite knee problems that haunted him throughout his career. When asked by a reporter after the 1912 season what his greatest asset was, he replied “plenty of grit.”14 He reportedly used the heaviest lumber in the American League, as his bats weighed between 53 and 56 ounces.

Gandil was sold to Cleveland before the 1916 season for a reported price of $7,500. One of the main reasons for the sale was supposedly the fact that Gandil was a chain smoker, occasionally lighting up between innings, which annoyed Griffith.15 In any event, the Indians also picked up Tris Speaker for that season, and things were looking bright in Cleveland. Although the Indians only climbed from seventh place to sixth, the team won 20 more games than the previous season, reaching the .500 mark. Gandil was unspectacular, batting only .259.

In February 1917 Gandil was sold to his original major-league team, the Chicago White Sox. A headline in the Chicago Tribune prophetically announced: “GET YOUR SEAT FOR ’17 SERIES! WHITE SOX PURCHASE GANDIL.” Manager Pants Rowland pushed White Sox owner Charles Comiskey to make the deal, and Tribune writer John Alcock described Gandil as “the ideal type of athlete — a fighter on the field, a player who never quits under the most discouraging circumstances, and so game that he is one of the most dangerous batters in the league when a hit means a ball game.”16

Gandil appeared in 149 games for the 1917 world champion White Sox, batting .273 with little power. He then hit .261 in the World Series win over the New York Giants, leading the team with five RBIs. Exempt from the draft because he had a wife and daughter, Gandil had a similar year in the war-shortened 1918 season, batting .271 in 114 games, as the White Sox slumped to sixth place.

After World War I ended, baseball owners, fearing a continued slump in attendance, cut back on costs wherever possible and shortened the season to 140 games. Gandil signed a contract for $666.67 per month, the same salary he had been making since 1914. But with the shortened schedule in place, his annual salary now worked out to $3,500 instead of $4,000.17

No one knows the full story of the Black Sox Scandal — few of the participants were willing to talk, and the whole plot was confused and poorly managed. But by all accounts Gandil, who claimed to be furious with Comiskey’s miserly ways, was one of the ringleaders. Most accounts agree that it was Gandil who approached gambler Sport Sullivan with the idea of fixing the Series, and that he also served as the players’ liaison with a second gambling syndicate that included Bill Burns (a former teammate of Gandil’s) and Abe Attell.18 Chick was also the go-between for all payments, and reportedly kept the lion’s share of the money. Though none of the other fixers took home more than $10,000 from the gamblers, Gandil reportedly pocketed $35,000 in payoffs.

It’s interesting to note that Gandil had a reasonably good Series. Although he hit only .233, that was the fourth best average among White Sox regulars. He was second on the team with five RBIs, and he had one game-winning hit. However, he made several suspicious plays in the field, and all but one of his seven hits came in games the fixers were trying to win, or in which they were already losing comfortably. Rumors of a Series fix began to circulate, with Gandil’s name prominently mentioned.

The next spring Gandil demanded a raise to $10,000 per year. When Comiskey balked, Gandil and his wife decided to remain in California. Flush with his financial windfall from the Series, Gandil announced his retirement from the majors, instead spending the season with outlaw teams in St. Anthony, Idaho, and Bakersfield, California.19 Thus Gandil was far away from the scene as investigations into the 1919 World Series began during the fall of 1920.

After the players’ acquittal on conspiracy charges in August 1921, Gandil said, “I guess that’ll learn Ban Johnson he can’t frame an honest bunch of ball players.”20 However, the players’ joy was short-lived, as Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis announced that the eight Black Sox were permanently expelled from baseball.

Gandil, who had retired from the major leagues anyway, continued to play baseball after his expulsion. A month after the trial he was in contact with Joe Gedeon, Swede Risberg, Joe Jackson, and Fred McMullin, attempting to put together a team in Southern California. In the mid-1920s Gandil played with Hal Chase, Buck Weaver, Lefty Williams, and other banished players in the Copper League, which had teams near the US-Mexico border in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.21

By the early 1930s Gandil and his wife had settled in Berkeley, California, where he worked mostly as a plumber.22 Around 1956, Gandil and his wife moved to Calistoga, in the Napa Valley. He had carbuncles, and the town’s mud baths and mineral springs aided his health.

To the end of his life, Gandil denied any role in fixing the 1919 World Series. In a 1956 Sports Illustrated article, he told writer Melvin Durslag that the players had planned to fix the Series, but abandoned the scheme when rumors began to circulate.23 In an interview with Dwight Chapin, published in the Los Angeles Times on August 14, 1969, Gandil again denied that he threw the Series, stating, “I’m going to my grave with a clear conscience.”

Chick Gandil died at the age of 82 in Calistoga on December 13, 1970, and was buried in St. Helena Cemetery in the nearby town of the same name. The cause of death was listed as cardiac failure. People in town had no idea of his fame, and his death reached the sports wires only due to the efforts of SABR founding member Tom Hufford.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015). This biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006).

Sources

Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 1, 1919.

Ginsburg, Daniel, The Fix Is In (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1995).

The files of Tom Shea.

Letter to Joe Gedeon dated September 15, 1921.

Saturday Evening Post, April 30, 1938.

Arizona Daily Star (Tucson), December 16, 1990.

Notes

1 Cleveland Press, March 17, 1916.

2 Leman Saunders, “Alias ‘Chick Arnold’: Gandil’s Wild West Days,” SABR Black Sox Scandal Committee Newsletter, June 2020, corrects the historical record on Gandil’s early days. Most baseball sources claim Gandil grew up in the Bay Area, but Chick spent most of his formative years in Southern California and he left home to play baseball years before his parents moved to Berkeley. In 1940 Gandil reported that he had completed four years of high school to US Census takers.

3 Saunders, “Alias ‘Chick Arnold.’ “

4 “‘Chic’ Gandil, the Man Who Started the Famous ‘Seventeen Straight,’” Baseball Magazine, August 1914, accessed online at LA84.org.

5 Chick Gandil as told to Melvin Durslag, “This Is My Story of the Black Sox Series,” Sports Illustrated, September 17, 1956.

6 New York Times, June 3, 1906; John Mason Hart, Revolutionary Mexico: The Coming and Process of the Mexican Revolution (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1997).

7 Ancestry.com, US Censuses 1920-40; Santa Rosa Press Democrat, December 14, 1970.

8 San Francisco Call, March 25, 1909.

9 Chicago Tribune, December 19, 1920.

10 New York Times, April 22, 1911.

11 Chicago Tribune, September 20, 1910; December 24, 1910.

12 Chicago Tribune, December 16, 1911.

13 “‘Chic’ Gandil, the Man Who Started the Famous ‘Seventeen Straight.’”

14 Chick Gandil player file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York.

15 Cleveland Press, March 17, 1916.

16 Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1917.

17 Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Spring 2012, Volume 6, Number 1 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.).

18 Bill Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial, and Civil Litigation. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013).

19 Idaho Statesman, February 23, 1920, and June 11, 1920; The Oregonian (Portland), September 29, 1920.

20 Chicago Tribune, August 3, 1921.

21 Lynn Bevill, “Outlaw Baseball Players in the Copper League: 1925-27” (master’s thesis, Western New Mexico University, 1988), accessed online at BevillsAdvocate.org.

22 United States Censuses, 1930-40, accessed online at Ancestry.com.

23 “This Is My Story of the Black Sox Series.”

Full Name

Arnold Gandil

Born

January 19, 1888 at St. Paul, MN (USA)

Died

December 13, 1970 at Calistoga, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.