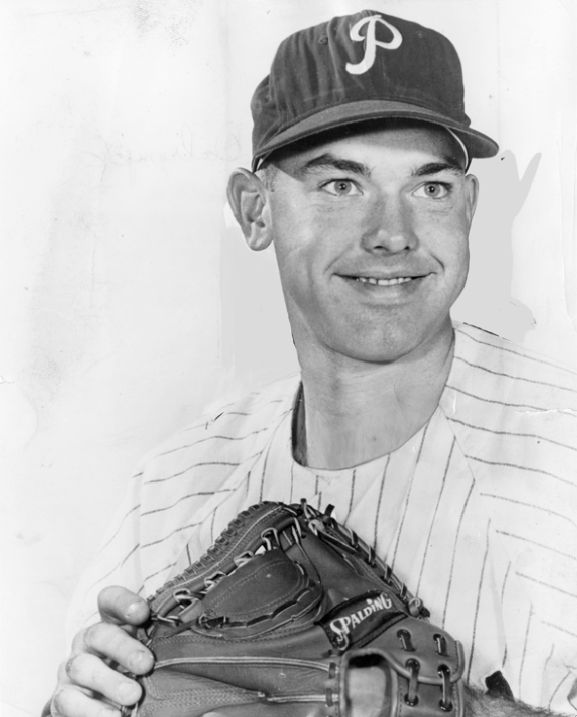

Clay Dalrymple

“I place a premium on a thinking catcher,” said Gene Mauch, who managed Clay Dalrymple for eight-plus seasons in Philadelphia.1 Mauch and another great tactician, Earl Weaver, both stressed pitching and defense. Thus, while Dalrymple’s hitting declined after his fourth year with the Phillies, his skills behind the plate kept him employed. The Californian handled pitchers deftly and threw out a superior 49% of the runners who tried to steal against him during his career. Dalrymple adjusted to Mauch’s platoons and then fit in well as a role player for Weaver from 1969 to 1971. Smart, skillful, and well-drilled, those Baltimore clubs won three straight AL pennants.

“I place a premium on a thinking catcher,” said Gene Mauch, who managed Clay Dalrymple for eight-plus seasons in Philadelphia.1 Mauch and another great tactician, Earl Weaver, both stressed pitching and defense. Thus, while Dalrymple’s hitting declined after his fourth year with the Phillies, his skills behind the plate kept him employed. The Californian handled pitchers deftly and threw out a superior 49% of the runners who tried to steal against him during his career. Dalrymple adjusted to Mauch’s platoons and then fit in well as a role player for Weaver from 1969 to 1971. Smart, skillful, and well-drilled, those Baltimore clubs won three straight AL pennants.

Unfortunately, Dalrymple was sidelined while the Orioles won their only World Series in that run. In June 1970, he suffered a broken ankle in a home-plate collision with Mike Epstein of the Washington Senators. Dalrymple watched the Series from the bullpen and was on hand for the victory celebration. “Yeah, I wear the ring. I really felt like I was a part of that team,” he said in 2008.

The memorable name of Dalrymple is Scottish – the clan’s motto is “Be firm.” Clay’s father, Lyndon, grew up in the Dakotas. He met his wife, Elsie Mae Henderson, in Alberta, Canada. The couple wanted to live in a warmer place, though, and so they moved to Chico, California, in the Sacramento Valley. During the Depression, Lyndon was an iceman. He then recapped tires for a service station in Chico and also drove a truck for Butte County. He and Elsie had four children: sons Leslie and Melvin, daughter Lois, and finally Clayton, who was born on December 3, 1936. Clay and his father shared the middle name Errol.

Chico, 90 miles north of Sacramento, is today a city of about 85-90,000. In 1940, though, it was just a town of 16,970 – with only two or three thousand in the center, as Dalrymple recalled. In author Debra Moon’s words, “Chico was a fun place. It had an ideal location for raising food and families.”2 Baseball was also popular. “The Chico Colts [semipro] baseball team drew a big crowd every Sunday afternoon for years. . . . They had some good players. Gordon Slade, a third baseman, later played with the St. Louis Cardinals and Cincinnati Reds [in the 1930s].”3

Lyndon Dalrymple’s athletic efforts were limited to some wrestling in his youth, but his sons all became part of the local baseball scene. The oldest brother, Les (1924-1999) played for and later managed the Colts. Les, also a catcher, was in the minor leagues in 1947 and 1948. He hit .309 and .278 for the Wenatchee Chiefs of the Western International League (Class B).

Another local star was the second Dalrymple brother, Mel (1928-2015).4 Nicknamed Bush, the lefty pitcher played six years with the Colts after graduating from Chico High in 1946. Some of his pitching records at Chico State College, now known as Cal State-Chico, remain unbroken. Most are from 1949, when he threw 11 complete-game wins in 11 starts. In 1950, Bush posted a 4-6, 5.97 record for Salt Lake City of the Pioneer League (Class C). A teammate and friend on the Bees was Hawaiian Wally Yonamine, who went on to the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame. Later, as head baseball coach at both Chico and Pleasant Valley High Schools, Bush instructed future big-league pitchers Nelson Briles and Pat Clements.

Dalrymple recalled that when he was a boy, “Chico was just forming Little Leagues at the time. The problem was getting enough kids together for teams in a small town – there were just enough for one.” He then followed the same pattern as his brothers: Chico High, the Colts, and Chico State. In his own view, he “was not way out in front of the other kids. My ability grew from year to year on a steady scale. I wasn’t one of those players who could have made it to the majors out of high school.”

Dalrymple’s first year with the Colts was 1954, his senior year in high school. It was then that Les stepped aside for his 17-year-old brother and became manager. Clay remained with the Colts during his first two years at Chico State (1955-56). Back in the mid-1950s, “we didn’t have the scale or the coaching that they do now.” Yet in something of a surprise for this good-quality program, it took nearly 50 years for the Wildcats to produce another big-leaguer. Drew Carpenter arrived in 2008, followed by Dale Thayer in 2009.

Dalrymple had good size (6’0” and 200 pounds) and also played football. “It was always interesting, and I enjoyed it. But baseball was far and away my favorite.” Otherwise, his most notable athletic endeavor was boxing. “I was a physical education major [at Chico State], and I had to give it a try as part of the curriculum. I really found how different it was to be one person, not part of a team. The day of a fight, you can really feel the butterflies piling up, a knot in your stomach. You don’t know, stepping into the ring, what you’ll get from your opponent.” In 1969, he joked, “My feet couldn’t stand to see my face take a beating.” However, with an 11-1 record, he became heavyweight champion of the Far Western Conference. “Seriously, it was a good character and confidence builder.”5

In August 1956, Dalrymple made his pro baseball debut with the Sacramento Solons of the Pacific Coast League. At that time, the Solons were not affiliated with any major-league club. “Don Masterson was a bird dog for Sacramento. He got into pro ball [1949-56, with two years away in Korea] but had an accident. A ball got through his catcher’s mask and broke some bones, and then he got a settlement. He told Sacramento I was a good prospect. But they couldn’t approach me, they would have gotten fined. So I called the general manager, Dave Kelley.”

The 19-year-old hit .286 with no homers and two RBIs in five games. In his first at-bat as a pro, he singled off future Red Sox hurler Jerry Casale, a 19-game winner with the San Francisco Seals that year. “I was scared and nervous. . . . I had the lightest bat I could find, but it felt like a two-by-four. . . . I could have had a double but stopped at first.”6 Not long after, he singled as a pinch-hitter for future big-league manager John McNamara. From the beginning, Dalrymple established a work ethic. “I had to do a lot of things for the organization to have them be pleased with my progress,” he said.

In 1957, Dalrymple was assigned to the Amarillo Gold Sox, a Class A team that had a working agreement with Sacramento. The left-handed dead pull hitter made the Western League’s All-Star team, hitting 17 homers and driving in 81 runs with a .298 average. He said of the city, “I like it fine. These are the friendliest people I’ve ever met.” A day after the season ended, on September 16, Dalrymple married the one he found friendliest of all, Celia Faye Creamer.7

During the offseason, Dalrymple went back to Chico State for more classes. (Teaching and coaching was his backup plan, though as it turned out, he never finished up his degree.) Meanwhile, the Solons reportedly turned down an offer of $50,000 for their prospect – which the financially strapped club could have used. In August 1958, The Sporting News noted, “Although Dalrymple has been hitting only around .190, General Manager Dave Kelley says he wouldn’t take $90,000 for him now.”8 He wound up hitting .191, with 5 homers and 21 RBIs.

After that PCL season, Dalrymple went to Venezuela, where he played with the Pampero Licoreros. As the team’s name suggests, the principal sponsor was a local distiller, mainly of rum. It’s no longer a mass-market presence, but Ron Pampero remains a high-end niche brand today. Its logo – a llanero, or Venezuelan cowboy – is a national symbol, evoking images of the rural plains. On these pampas one also finds sugar cane plantations . . . and, at least in the past, baseball.

The Pampero club actually played in the capital city, Caracas. The Dalrymples – Clay, Celia, and baby daughter Dawn – shared a house in the American section with pitcher Joe Stanka and his family. In 44 games for the Licoreros, Dalrymple batted .276, with 2 homers and 16 RBIs. He remembered getting a cut forehead from a piece of glass that came from the stands as he strapped on his shin guards. Aside from that, his lasting image was of the stadium vendors. “They would go around with a Thermos and these little cups. I thought it was whisky, but I found out it was a strong shot of coffee.

“It was quite an interesting time. The people were very warm and friendly, and I enjoyed

it there. But at the end of the Venezuelan season, Cuba still had another month to play,” he continues. “So I went there. I was recommended by Chuck Churn. It was right after Castro had taken over. The military wanted to show how big and tough they were. Once I was ushered off a plane by a guy with a rifle and bullets hanging off his chest. It kind of frightened my wife, but I was never in any danger, though.”

Dalrymple went 7 for 62 (.113) with no homers and 3 RBIs for Habana as a backup to John Romano.9 “That was the end of my winter ball experience. It was mainly family reasons, but I found other jobs. I drove a cement truck one year, and I was also with the Southern Pacific Railroad [as a rodman].”

Before the 1959 season rolled around Stateside, at least one veteran baseball man saw beyond Dalrymple’s .191-5-21 batting line at Sacramento the previous year. That was Red Davis, then manager of a PCL opponent, the Phoenix Giants. In an article that focused on Vada Pinson and Claude Osteen, Davis remarked, “There’s a young catcher who got little recognition but I sure like him. He is Clay Dalrymple. He’s a left-handed hitter with good power and is a good receiver. Don’t let his .191 average fool you. I had him on my All-Star club and he hit a homer with two on and caught the last four innings.”10

The Milwaukee Braves, who had a working agreement with the Solons, must have spotted the prospect too, for they invited Dalrymple to spring training in 1959. He returned to Sacramento, though, improving to .230-12-48 with the bat. After the season ended, The Sporting News observed, “The work horse of the mask-and-mitt men in the PCL, he appeared in more games (121) than any other receiver in the circuit and was the leader in flagging would-be base stealers, throwing out 33.”11

That article followed the minor-league draft on November 30, in which the Phillies selected Dalrymple on the recommendation of Dave Kelley, who had become their Far West supervisor of scouts. Dalrymple later told author Robert Gordon, “At the time, [Milwaukee] had a great team and a great catcher, Del Crandall. I didn’t see much opportunity for myself with the Braves with Crandall there. I was happy when the Phils drafted me. . . . I knew I had a chance to play.”12

The Sporting News called Dalrymple and fellow draftee Bobby Malkmus “both strictly gambles.”13 Even so, both made the Phillies team in spring training 1960. As the season opened, veteran catcher Valmy Thomas was sent down to Indianapolis. Scrappy but light-hitting Jim Coker caught every inning of the first 10 games before Dalrymple made his debut in the nightcap of a doubleheader on April 24. Don Newcombe, then with Cincinnati, struck him out looking – but in his next at-bat, Dalrymple doubled off Newk.

Dalrymple initially made his mark as a pinch-hitter, going 12-for-42 in that role in 1960. One of those hits came in Juan Marichal’s debut on July 19 – and it was the only one the high-kicking Dominican allowed that day. Dalrymple was “assigned to veteran receiver Cal Neeman to learn how to improve his defensive skills.”14 Neeman came over in the Tony Taylor trade on May 12; Dalrymple thought that Coker “was always a little cool to me ’cause he thought I was out for his job.”15

The receiver already possessed a vital knack. “Impressed with his pitch-calling, Phillies ace Robin Roberts went to Mauch and asked that the young backstop catch him on a regular basis, and, by August, Dalrymple was the team’s regular catcher as well.”16 He finished the year with .272-4-21 totals in 158 at-bats.

In spring training 1961, Dalrymple suffered a case of the “yips” – he had problems even throwing the ball back to the pitcher. “I had a bad arm,” Dalrymple said. “And then it became a mental thing. The exact same thing Steve Sax went through with the Dodgers.”17 He also had an ice-cold first half at bat. However, while the team endured a 23-game losing streak from late July through most of August, the catcher came around in the second half and lifted his average to .220. Gene Mauch observed, “Dalrymple has sure improved . . . from midseason on he led the club in hitting and he gained confidence in his ability to handle a game.”18

Dalrymple (already balding in his mid-20s) had his best hitting year in 1962: .276, 11 homers and 54 RBIs, with 70 walks as well. The next year, after a winter of diet and exercise, he posted career high in games (142) and at-bats (452).19 In 1964, though, Mauch decided to go with a platoon behind the plate. “Although the Phils’ veteran catcher was not too happy about splitting time with the recently acquired [Gus] Triandos, he understood the benefit of platooning. ‘Having Gus here ought to mean a better year for the club and for me,’ he admitted. ‘This year we should get a solid .270 out of both catchers.’”20

However, Dalrymple went into a funk with the bat and never recovered. “For some reason, I developed a hitch in my swing – just one of those mechanical things. We didn’t have a hitting coach. We didn’t have videos either. I never fixed the problems the rest of my career. I just stopped hitting.”21

Nonetheless, he remained a key contributor to the club that looked certain to win the NL pennant. As ever, he handled pitchers capably. He also sought out talented but divisive star Richie Allen after a contentious team meeting, telling Allen “that he was a smart guy and that he had some great leadership qualities. I guess he didn’t appreciate all the talent he had at that time, though.”22 Dalrymple noted in 2008, “Richie Allen and I were very close. I roomed with Pat Corrales and they were close – all three of us were.” There weren’t many African-Americans in Chico when Dalrymple was growing up, and he was shocked to see the treatment they received in the Deep South.

Many writers have covered the Phillies’ notorious “September Swoon” in depth. Author William Kashatus devoted an entire book to it in 2005, and in 1989, veteran Philadelphia journalist Stan Hochman came out with a series on the players. Dalrymple was one of their featured interviewees. He commented on the many ingredients that went into the collapse:

- The most debatable factor, of course, was how Gene Mauch handled his pitchers down the stretch. Dalrymple told Kashatus that the “bullheaded” and “panicking” skipper gave up on Ray Culp and Art Mahaffey, viewing the former as overweight and both as lacking guts.23

- Hochman heard that when Frank Thomas suffered a broken thumb, the team went from aggressive to defensive.24

- Dalrymple himself suffered a strained knee in September as he dived back into first base on a pickoff attempt in September. “I hit the ground real hard. They were going to drain some water off my knee, but there was a skinned-up mark there and we didn’t want to put the needle in that.”

- Ultimately, though, he said to Hochman, “Not one thing is at fault. Not one single thing can you put your finger on. Lose that many in a row with that big a lead, everyone had their finger in the pie.”25

Dalrymple recognized Mauch’s special acumen. “Gene manipulated his players on the field better than anyone I ever played for,” he said after the manager’s passing in 2005.26 However, in 1968, some months after

Mauch was fired, Dalrymple also remarked on the flip side of this habit. “Gene is a great manager but he will not let the players ‘play the game.’ . . . He wants to play the game from the dugout.”27

Only someone as strong-minded as pitcher Jim Bunning could break free of Mauch’s micromanaging. In his book, the future U.S. senator observed, “Clay had been trained to look for Mauch’s every sign. As soon as Clay put down the sign, I changed it. . . . and Dalrymple finally said, ‘I’m not even going to look anymore.’ Clay found out Mauch was not going to object. . . . We played much faster games that way. It was so much easier.”28 However, it was Gus Triandos, not Dalrymple, who caught Bunning’s perfect game on June 21, 1964.

On a personal level, a truly heartwarming story from the ’64 season came as Dalrymple befriended a little blind girl who attended games at Connie Mack Stadium. The catcher took his “biggest fan” onto the field after one game and escorted her from home plate around all the bases for her to feel them. “She was just so overjoyed,” he told Kashatus, “It was probably the biggest ovation I ever received.” Dalrymple was still nearly overcome with emotion nearly forty years later. “Fans like that little girl made my entire career worthwhile.”29

Dalrymple also developed his personal touch in Philadelphia as an after-dinner speaker. “I would get $35 for appearing at Little League banquets. You get a feeling for yourself – it’s good for your personality. Stabilization.” He was the guest of many community groups over the years.

From 1965 through 1968, Dalrymple remained in a platoon with various other catchers, none of whom hit well. After Triandos was sold to Houston in June ’65, Dalrymple’s partner was Pat Corrales. Bob Uecker, Gene Oliver, and the even lighter-hitting Mike Ryan followed. Dalrymple’s defense remained sharp – he set a league record, since broken, with 99 consecutive errorless games (and 628 chances) during 1966 and 1967. Yet the notoriously harsh Philly boo-birds piled on him.

“The pressure of playing before fans who weren’t appreciative was too much,” Dalrymple observed in 1969.30 A few decades later, he added, “The fans were brutal to me toward the end. Eventually I told the Phils, ‘You should trade me. I’m not doing you any good here.’”31

Dalrymple’s wish was granted – he went to the Orioles for outfielder Ron Stone on January 20, 1969. Earl Weaver – “a good manager and a good man, though his personality left something to be desired” – had taken over at Baltimore in mid-1968. He always liked to have a deep bench with a lot of capable role players. Although he already had a catching platoon with righty Andy Etchebarren and lefty swinger Elrod Hendricks, Earl typically carried three catchers on his roster. Curt Blefary had been traded and Larry Haney had been lost to Seattle in the expansion draft. Weaver also aimed to have three righty and three lefty bats available. Dalrymple’s experience and defensive skill added maneuverability and insurance against injury.

At that stage in his career, Ellie Hendricks was still viewed as more of a hitter and a “project” behind the plate.32 As Hendricks worked to smooth off his rough edges as a catcher, Dalrymple did not mentor him. “I did not feel it was my duty. He was the number-one catcher. Weaver wanted to write his name in the lineup. It would piss Earl off when pitchers would ask for me.” Still, Dalrymple and Hendricks, a good-humored Virgin Islander, got along well (it was almost impossible to dislike Ellie), exchanging locker-room banter.

“Etchebarren and I were pretty close,” Dalrymple observed. “He had a history of breaking a hand [broken right metacarpals in both 1966 and ’68]. You should have seen the mitt he had, it was tiny and thin with a little pocket – such a miserable piece of equipment. I told him, ‘That thing must date back to 1912.’ It was his right hand that would get broken because he’d have to reach in there with it. I got him to switch, and no more broken hands.”

As a backstop, Dalrymple upheld the classic fundamentals. “The mitts you see today, that are more like a first baseman’s glove – they lead to backhanding, rather than shifting your weight and receiving the ball. Elrod was a snagging-type catcher.” The cost is framing pitches and getting borderline ball-and-strike calls. “The mitt I have bronzed today, it was one of the first from Rawlings that had the cross-webbing. I used that for plays at the plate [his bid to carry a fielder’s glove in an enlarged back pocket for this purpose was turned down by the league office later in 196933]. For pitches, I formed a big round pocket, a nice target that the pitcher could see.”

The mental game was a major dimension for the Baltimore pitchers, notably Jim Palmer and Mike Cuéllar. Palmer often battled his catchers, but Dalrymple’s flexible approach avoided this. “I would find out how a pitcher’s mind works. You call a game according to how the pitcher wanted, not how you wanted.”

Playing time was scarce for Dalrymple, though he had a case for more, and he noted that this made it more difficult to stay sharp.34 He played in just 37 games during the regular season in ’69, going .238 with 3 homers and 6 RBIs in 80 at-bats. Dalrymple did not appear in the playoffs against the Twins, but in the World Series, he went 2-for-2 as a pinch-hitter. “You can win a bar bet with that,” he said with a laugh. In Game Three, he singled off Nolan Ryan of the Mets in the ninth inning. Then in Game Four, with Dave Johnson on first and one out in the 10th, he had another single off Tom Seaver. However, the Mets ace got the next two outs, and J.C. Martin’s bunt won it in the bottom of the inning.

In 1989, Dalrymple recalled to Stan Hochman that as the ’69 season began, he said to Andy Etchebarren, “If we were allowed to bet, I’d put every nickel on this ballclub. It was the best team I’d ever, ever seen.”35 He echoed that view in 2008, noting the strength of the pitching. Yet a couple of months after the Amazin’ Mets pulled off their upset, he noted that while the Mets had gathered momentum late, the Orioles were flat. “We played our best earlier. The second half was like a cakewalk. . . . There’s no doubt that the reason was lack of excitement.”36

During the first few months of the 1970 season, Dalrymple’s action was even more limited (.219-1-3 in 32 at-bats in 13 games). On June 27, however, he got one of his infrequent starts, in a Saturday night game at Robert F. Kennedy Stadium in Washington. “Palmer insisted that I catch him. In the third or fourth inning, I could see he wasn’t on his game – I was nursing him along.” Then in the bottom of the seventh, Frank Howard and Mike Epstein singled. Aurelio Rodríguez followed with a double to left. “It was in the gap, and the relay came from [Paul] Blair to [Mark] Belanger to me. The throw bounced high off the grass, and when I turned around, Epstein’s eyes were barely two feet away from my chest.

“I had put my left foot in front of the plate. I gave him the back edge to slide to. But Epstein, who was a fullback in college football, decided to take me out. My right ankle popped – it was dislocated and broken in two places.

“There was no pain in the ankle at the time – it was really gathering in the knee. The pain was too great for the ankle to register, so it went to the next place, the doctor said.” Dalrymple was taken off the field on a stretcher, yet he never lost consciousness. The great play held a 3-2 lead for the O’s, but Palmer lost it in the eighth inning.

“To show you the camaraderie and the sick humor we had on that team, let me tell you about my friend Merv Rettenmund. Merv’s the kind of guy who would joke, even though he’s been married to the same woman all his life, ‘Why is it that when I come home from a road trip, I always hear the back door slam?’ Well, I was there

in the hospital with my foot so badly deformed that my toes were pointing in different directions. Merv brought in a card that said, ‘Best wishes from your last team.’ But I didn’t get pissed off. . . . I laughed my ass off.”

The cast came off three months later, just before the World Series. “I tried to do a little bit of jogging, but it was really sore and there were adhesions.” Thus Dalrymple remained inactive for the Series. Also, though he was able to rejoice with his teammates, privately he and his wife were facing an ordeal. Celia had been diagnosed with the cancer that would eventually claim her life two years later. Her Christian Scientist beliefs dissuaded her from the minor surgery that might have caught the disease early.

Dalrymple was able to come back in 1971, with hockey as part of his winter rehab.37 “I got the screw out of the ankle and broke the adhesions loose.” Again he played sparingly (23 games, .204-1-6 in 49 at-bats), but he did make the postseason roster. However, he did not appear in either the playoffs or the World Series (though he did provide some scouting reports on Pittsburgh batters). “I was in the on-deck circle one time against the Pirates, but the hitter before me made the last out.” Tongue in cheek, he added, “I think Weaver wanted me to put my 1.000 lifetime [World Series] average in jeopardy!”

Later that October, the Orioles left on one of the periodic American postseason tours to Japan, and Dalrymple was there. Though he did not get into a game, he said, “It was such a fun trip. It was about goodwill – winning and losing was not the most important thing. Etchebarren was my roommate. I learned a few Japanese words from a book that I kept in my back pocket, and I knew the menu. It pissed Etch off that I would out-order him! I was only there about a week, though, when I got word that my wife had to go back into the hospital. I cut it short.”

Not only was Celia ill again, the Orioles sent Clay a message by leaving him off the 40-man roster and assigning him to Triple-A Rochester. So that December, at age 35, he retired after 12 seasons in the majors. Beyond his 55 homers, 327 RBIs, and a .233 average, “I’ve fulfilled my baseball dreams,” he said.38

It’s worth reiterating his most impressive big-league stat, though: 306 runners caught stealing against 320 successful. Even as the third-string catcher with the O’s, each year there he nailed over 50% (25 out of 44 total). Analyst Chuck Rosciam compiled this statistic across the majors from 1956 through 2007. Over more than half a century, Dalrymple ranked second only to Roy Campanella (whose entire career was available for study).39

Dalrymple credited his quick release more than his arm strength. “Every instant, every split second counted. Facing somebody like Maury Wills, I thought, what do I have to do to cut him down? It was always going to be a bang-bang play anyway. Grab the ball and don’t look for the seam – get rid of it. It was almost a sidearm throw sometimes.”

Celia Dalrymple, aged only 34, passed away in November 1972.40 Clay then felt compelled to stay with their three daughters, Dawn, April, and Autumn (whom they had adopted eight years after April was born). In 1989, he said, “What was I to do with the kids? After losing a mother, they were going to lose a father, too? Dallas Green offered me a good job with the Phillies organization just before Celia passed away. I would still be in baseball in some capacity. I think about it occasionally, but I don’t dwell on it.”41 In 2008 he added, “I would probably have started managing in the minors. I could have gone into the front office.”

Dalrymple continued to work for a plumbing wholesaler, a job that originally started in the offseason in Philadelphia in 1964. During 1976 and 1977, he also served as a color man on Orioles TV broadcasts. “Bill O’Donnell and Chuck Thompson [Baltimore’s longtime announcers] got me in. They would alternate between radio and TV, and I would join whoever was on TV. I did it for two years, right at the end of Brooks Robinson’s career. Then when he retired, I interviewed him and found out he was going to take my job! But Brooks is an Orioles legend and a great guy.”

Around 1982, Dalrymple returned home to Chico. “I was offered a job in cable TV [back east], just as it was exploding. But I’m a small-town guy. I missed my brothers. I missed hunting and fishing. Plus, I had gotten remarried and that wasn’t working out.” Back in California, he held a sales job with Allied-Sysco Food Services. He later worked for another food distribution company, S.E. Rykoff, before retiring in 1998.

In 1987, Dalrymple was inducted into Chico State’s Athletic Hall of Fame. Eighteen years later, he was part of the inaugural class of the Chico Professional Baseball Hall of Fame, along with former Cincinnati star pitcher Gary Nolan. (Brothers Bush and Les later joined him.)

Since 2001, Dalrymple has lived in Gold Beach, Oregon. “It’s a more moderate climate – it can get up to 115 or 118 degrees in the Sacramento Valley in the summer. Some of it was taxes too; the politics are so far left in California.” After his second divorce and losing another wife to sudden death, he stated, “I’m very happy now” with his fifth wife, Teresa. Clay and Teri enjoyed gardening, both vegetables and flowers.42

For a couple of years, Dalrymple helped coach the local high school baseball team. “It was very unofficial. I was doing it just because I wanted to. But I found there was too big an age gap, I wasn’t communicating properly. I don’t have the patience any more.” He also noted, “I know things about catching that I can’t teach. You have to experience it.”

One town over to the east, in Agness, Oregon, Hall of Famer Bobby Doerr was still living as of 2017. In April 2008, Dalrymple helped the old Red Sox second baseman celebrate his 90th birthday. “He’s just starting to show his age. Myself, I’m starting to feel that old broken ankle now.” Dalrymple served as a commissioner for the local port district, but that was not his most avid pursuit. “I’m a news junkie,” he said. “I follow politics very closely. I write articles, I’m a conservative. I enjoy writing about politics more than anything.” In 2017, with President Donald Trump in the White House, he continued to express his beliefs with letters to the editor of a local newspaper, the Curry Coastal Pilot.

Dalrymple saw his old champion Oriole teammates – “those of us who are still here” – at a March 2008 autograph show in the Baltimore-Washington Airport. Among the other guests was Reggie Jackson. Once he realized who Dalrymple was, Reggie recalled with pleasure how, as a teenager growing up just north of Philadelphia, he had watched the catcher at Connie Mack Stadium. The show also gave the old banquet speaker a chance to flash his relaxed, self-deprecating sense of humor.

“The line for Frank Robinson was snaking all the way around the place when they announced me. About ten minutes went by. . . . I had nobody. I looked at the guy at my table with all the different kinds and colors of pens and I said, ‘Watch this.’ I stood up and made an announcement. ‘Can I have your attention, please?’ There was silence. I said, ‘I know it’s crowded over here, and you’re gonna have to be patient – but if you bear with me, I just might be able to squeeze you in!’

“The place broke up laughing. Then I got a nice group of people and we talked about baseball.”

Neither a star nor a “character,” Clay Dalrymple still struck a chord with many fans. If you appreciate honest artisans and the game’s subtle nuances, you could be one of them.

Last revised: April 5, 2017

This biography is included in the book “The Year of the Blue Snow: The 1964 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2013), edited by Mel Marmer and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

An alternate version of this biography also appeared in SABR’s “Pitching, Defense and Three-Run Homers: The 1970 Baltimore Orioles,” published by the University of Nebraska Press in 2012.

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Clay Dalrymple for his memories (phone interviews, May 11 and May 23, 2008). All quotes from him are from these interviews unless otherwise indicated.

Thanks also to Alfonso Tusa (Venezuelan stats).

Sources

www.goldenbaseball.com/Chico

Professional Baseball Players Database V6.0

Daniel Gutiérrez, Efraim Álvarez and Daniel Gutiérrez, Jr., La Enciclopedia del Béisbol en Venezuela, Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Norma, 2007.

Notes

1 Bob Fowler, “Twins Sing the Praises of Unsung Borgmann,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1979, 17.

2 Debra Moon, Chico: Life and Times of a City of Fortune, Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2003: 134.

3 Ibid.

4 “Melvin R. ‘Bush’ Dalrymple,” Chico Enterprise-Record, February 26, 2015.

5 Doug Brown, “Clay Nixed Ring Career After Heavyweight Fling,” The Sporting News, February 22, 1969, 38.

6 Eddie Mullens, “Mullen It Over,” The Amarillo Globe-Times, July 30, 1957, 12.

7 Ibid.

8 The Sporting News, August 27, 1958, 42.

9 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005: 452.

10 John (Red) Davis, “Seattle Sends Pinson And Osteen, Two Fine Prospects, To Cincinnati,” Raleigh Register (Beckley, West Virginia), April 22, 1959, 6.

11 Oscar Kahan, “Phils, Tigers, A’s Dip Into Grab Bag Twice,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1959, 12.

12 Robert Gordon, Legends of the Philadelphia Phillies, Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2005: 44.

13 Allen Lewis, “Phillies Banking on Malkmus for 3rd Time Charm,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1959, 16.

14 William C. Kashatus, September Swoon: Richie Allen, the ’64 Phillies, and Racial Integration, State College, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005: 54.

15 Gordon, op. cit., loc. cit.

16 Kashatus, op. cit., loc. cit.

17 Stan Hochman, “The Survivors of ’64: Part Three – Clay Dalrymple,” Philadelphia Daily News, July 18, 1989, 68.

18 Allen Lewis, “Phils Size Up Dalrymple As Top Backstop,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1961, 22.

19 Allen Lewis, “Dalrymple Pays Double Dividend – Behind Dish, At Bat,” The Sporting News, February 2, 1963, 11.

20 Kashatus, op. cit., 68.

21 Gordon, op. cit., 44.

22 Kashatus, op. cit., 193.

23 Kashatus, op. cit., 139.

24 Hochman, op. cit.

25 Hochman, op. cit.

26 Sam Carchidi, “Gene Mauch: a strategist * an innovator * a great manager,” Baseball Digest, December 1, 2005.

27 John Ribar, “Dalrymple: ‘He Played Our Game,’” Bucks County Courier Times (Levittown, Pennsylvania), October 31, 1968, 31.

28 Frank Dolson, Jim Bunning: Baseball and Beyond, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Temple University Press, 1998: 85.

29 Kashatus, op. cit., 109.

30 Doug Brown, “Dalrymple Pleased to Escape Wrath of Critical Philly Fans,” The Sporting News, February 22, 1969, 38.

31 Gordon, op. cit., 45.

32 Doug Brown, “Clay Ticketed for Backup Catching Job With Orioles,” The Sporting News, February 8, 1969, 41. Phil Jackman, “Stronger Bench Causing Orioles to Raise Sights,” The Sporting News, April 12, 1969, 27.

33 Phil Jackman, “Clay’s Extra Glove Puzzle for Umps,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1969, 42.

34 Doug Brown, “Bench-Rider Role Can Tire You Out, Dalrymple Claims,” The Sporting News, December 13, 1969, 39.

35 Hochman, op. cit.

36 Brown, “Bench-Rider Role Can Tire You Out.”

37 Phil Jackman, “Goalie Dalrymple Prefers Catching,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1971, 33.

38 “Clay Dalrymple Hangs ’Em Up,” Delaware County (Pa.) Daily Times, December 15, 1971, 27.

39 Chuck Rosciam, The Encyclopedia of Baseball Catchers, http://members.tripod.com/bb_catchers/catchers/

40 “Mrs. Celia C. Dalrymple,” Amarillo Globe-Times, November 16, 1972, 47.

41 Hochman, op. cit.

42 Randy Robbins, “Innominata tour celebrates 20 years,” Curry Coastal Pilot (Brookings, Oregon), July 17, 2013.

Full Name

Clayton Errol Dalrymple

Born

December 3, 1936 at Chico, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.