Dazzy Vance

Could a friendly poker game among minor-league teammates lead to a Hall of Fame career for a 29-year-old who had been pitching in professional baseball for nine years, never had won a major-league game, and seldom had put together two good years back to back in the minors? Perhaps. Arthur Vance had earned the nickname Dazzy for the dazzling fastball he had shown as a teenage semipro in rural Nebraska. He even had two shots at the major leagues, but nary a victory there as his total big-league record consisted of zero wins and four losses. In the minors he showed occasional flashes of brilliance, but his best performances were usually followed by a sore arm and a disappointing next season. He was with the New Orleans Pelicans in the Southern League that evening when the fateful poker game occurred.

Could a friendly poker game among minor-league teammates lead to a Hall of Fame career for a 29-year-old who had been pitching in professional baseball for nine years, never had won a major-league game, and seldom had put together two good years back to back in the minors? Perhaps. Arthur Vance had earned the nickname Dazzy for the dazzling fastball he had shown as a teenage semipro in rural Nebraska. He even had two shots at the major leagues, but nary a victory there as his total big-league record consisted of zero wins and four losses. In the minors he showed occasional flashes of brilliance, but his best performances were usually followed by a sore arm and a disappointing next season. He was with the New Orleans Pelicans in the Southern League that evening when the fateful poker game occurred.

Arthur Charles Vance,1 who spent the second half of the 1934 season with the St. Louis Cardinals after a Hall of Fame career with the Brooklyn Robins/Dodgers, was born near the village of Orient in Adair County, in southwestern Iowa, on March 4, 1891, the fifth child of Sarah Elizabeth (Ritchey) and Albert Theophilus Vance, a farmer. While Arthur was still a small child the family moved to a farm in Pleasant Hill Township in Webster County, Nebraska, near the Kansas state line. The youngster attended Hardy High School, but made his baseball reputation by pitching for a semipro club in nearby Hastings. He married Edythe Carmony, daughter of Thomas Carmony, a railroad employee in Hastings, and his wife, Martha. The newlyweds established their home in Hastings and maintained a residence there until 1925. Their son, Bob, was born there in 1918 and a daughter came along a few years later.

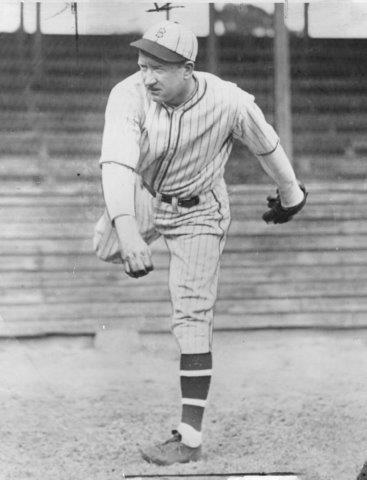

The fire-balling right-hander, who stood 6-feet-2 and weighed 200 pounds, broke into professional baseball in 1912 at the age of 21 with the York Prohibitionists in the Class D Nebraska State League. For a few years he advanced up the minor-league ladder. In 1914 he split the season between the Nebraska State League and St. Joseph, Missouri, of the Class A Western League, winning 26 games. But he strained his arm by pitching four games in six days. After that his arm usually gave out soon after the season began and he moved on to another team. “Something went wrong with my right arm,” he said. “I no longer could throw hard, and it hurt like the dickens every time I threw.”2 In the spring of 1915 his contract was purchased by the Pittsburgh Pirates. He lost his major-league debut on April 16 and was promptly dealt to the New York Yankees, where he lost all of his three decisions. The Dazzler had failed to dazzle big-league hitters. The Yankees sent him back to St. Joseph. In 1916 he was promoted to Columbus, Ohio, of the Double-A American Association, but he developed arm trouble and bounced back and forth between A and Double-A clubs for the next several years. The Yankees gave Vance medical treatment and sent him to various minor-league clubs on option over the next several years. The Yankees gave him another major-league trial in 1918, but he failed miserably (with an ERA of 15.43 in two games). After two years in Memphis, Rochester, and Sacramento, the sore-armed hurler found himself in New Orleans in 1920.

It was in the Big Easy that the career-changing poker game occurred. According to Jack Kavanagh and Norman Macht,3 Vance banged his arm on the edge of the table while raking in a pot. He immediately felt intense pain. When the arm still hurt the next morning, Vance went to a doctor, who diagnosed an underlying injury that had not been discovered by all the medicos who had examined him previously. Exactly what the doctor did is unknown. Bill James4 speculated that the surgeon probably removed bone chips and debris from the elbow. That guess seems as good as any. At any rate, the operation was a success and the patient not only survived, but he thrived. After receiving this treatment, Dazzy was able to pitch again painlessly. The Dazzler rebounded to win 21 games for the Pelicans in 1921, his first 20-win season since 1914. He made it to the majors to stay the very next year. “It was an odd thing,” Dazzy later recalled. “My arm came back just as quickly as it went sore on me in 1915. I awoke one morning and learned I could throw without pain again.”5

One of Vance’s teammates in New Orleans was a highly regarded young catcher named Hank DeBerry. The Brooklyn Robins were in need of a catcher and attempted to recruit DeBerry. Frank Graham6 wrote about the signing of DeBerry and Vance. Charley Ebbets, president and principal owner of the Robins sent Larry Sutton, his top scout, to New Orleans to inquire about acquiring DeBerry. Sutton replied that DeBerry looked like a good prospect, and he could be had for a fair price, but there was a catch to it. The Pelicans wanted them to take a pitcher, too. When he found out that the pitcher in question was Vance, Ebbets rebelled. “Oh, no,” he said. “I could have drafted him long ago if I wanted him. You go back and tell them if we have to take Vance the deal is off.”

Soon Sutton called his boss back. “They say, no Vance, no DeBerry.”

“In that case, “Ebbets replied, “tell them they can …” Sutton interrupted: “Wait a minute, Mr. Ebbets. I just talked to DeBerry. He wants to go to Brooklyn, naturally, but he says he don’t want to go without Vance. He says to tell you that if he looks good down here, it’s because Vance makes him look good. And, really, Daz is hot. He’s knocked around a long time and he’s learned how to pitch. And he has a fastball. A real good fastball. He’s the best pitcher in the league.”

According to Graham that is how Dazzy Vance at the age of 31, after ten years in the minors and 133 minor-league wins, finally made it to the majors to stay. At an age when some pitchers are beginning to slow down, the Dazzler was just getting started on the road to the Hall of Fame. Vance made an impressive showing during the Robins’ spring training and won a spot in the starting rotation. He made his 1922 debut on April 13, pitching a complete game to batterymate DeBerry but losing to the New York Giants, 4-3. He achieved his first major-league victory on April 26 at Braves Field, defeating Boston’s spitballer Dana Fillingim, 10-1. Daz pitched a complete game, allowing seven hits, walking five, and striking out four. He helped his own cause by collecting three hits at the plate, including a double, and driving in two runs. Vance hurled a league-leading five shutouts that year. He won 18 games in each of his first two seasons in Brooklyn and led the NL in strikeouts both years, starting a string of seven straight strikeout championships. Although Vance is remembered primarily as a fastball pitcher, he also had a devastating curve, with which he finished off many batters. Kavanagh and Macht wrote: “Dazzy’s pitching style was simple. He reared back, kicked his left foot high and catapulted the ball overhand. It exploded past the batter or swerved away. Although his speed excited the fans, it was his control of the curve that delighted his manager.”7

Dazzy had his best season in 1924. He won the mythical Triple Crown Award for pitchers by leading the league in wins (28), ERA (2.16), and strikeouts (262). At one stretch he won 15 straight games. He also led the circuit with 30 complete games en route to winning the league’s Most Valuable Player Award, the only NL pitcher to cop that trophy until Carl Hubbell did it in 1933. Instead of awarding a trophy for the MVP Award, the National League presented Vance with $1,000 in gold coins. Vance set a league record for strikeouts in a nine-inning game by fanning 15 Chicago Cubs on August 23. One month later he came back against the Cubs and struck out the side on nine pitches. Vance and Burleigh Grimes became the only teammates to rank one-two in strikeouts in the NL between 1905 (Mathewson and Ames) and 1960 (Drysdale and Koufax). On July 20, 1925, Vance struck out 17 St. Louis Cardinals in a ten-inning game.

They were quite a pair – Vance and Grimes. The two were both great pitchers, but they had little else in common. Dazzy was a fun-loving flake; Burleigh was grim, dour, and dead serious on the mound and in the clubhouse. Uncharacteristically, Grimes joined Vance and two or three teammates in one after-midnight episode, not out on the town, but in a Pullman car. After a series against the Giants in Flatbush, the Robins took a midnight train for Boston and found that the Braves, who had just finished a series in Philadelphia, were on the same train. The miscreants cut eyeholes in pillowcases, pulled them over their heads, and invaded the Braves’ sleeping car. Announcing that they were the Ku Klux Klan, the miscreants awakened the Boston players and dragged some of them out of bed. When they found catcher Mickey O’Neil they demanded to know what his signs were, and the terrified backstop eventually told them.

By the mid-1920s the Brooklyn club was being referred to less as the Robins and more as the Dodgers. One contingent of the team was being called the Daffiness Boys. During the first game of a doubleheader on August 15, 1926, against the Boston Braves that nickname was firmly established by the famous three men on third base misadventure. Although he was not to blame for the incident, Vance was right in the middle of the mix-up. He was on second base and Chick Fewster was on first when rookie first baseman Babe Herman hit a long drive to the outfield. As the Babe rounded second, the third base coach yelled at him to go back as Fewster had not yet reached passed third. Vance had already rounded third and was heading for home, but he thought the coach was yelling at him and headed back to third. About this time Fewster reached third, and Herman ignored instructions and also chugged into the bag. To the everlasting hilarity of baseball fans, the Dodgers had three men on third base at the same time. (The third baseman tagged Fewster and Herman for two outs, but Vance was ruled safe because by arriving first he had a legitimate claim to the base.) Herman had doubled into a double play.

Babe Herman had a reputation as the daffiest of the Daffiness Boys, but Dazzy Vance was undoubtedly their leader. He even had a title – president of the “4 for 0 Club,” so named for their penchant of getting no hits in four at-bats. According to Graham, Vance carried the farce to the extent of drawing up bylaws for the club, including “Raise all the hell you want but don’t get caught.” Pitcher Jesse Petty violated that rule. He got caught by manager Wilbert Robinson coming into the hotel after a late-night party. Robbie fined him. Worse yet, Vance expelled him from the club. When Petty asked teammates to intercede for him, they refused. Jesse took his woes to baseball writer Joe Gordon. The scribe composed a letter of apology pleading for the hurler’s reinstatement. Petty copied the letter, signed it, and left it in Vance’s mailbox. That night Jesse was summoned to Vance’s room for a hearing.

“Did you write this letter,” Dazzy asked.

“Yes.”

“You are not only a big dope to be caught by Robbie, but you are deceitful as well. There are words in this letter that you can’t spell and don’t know the meaning of.”

Petty’s expulsion from the club was made permanent.8

While pitching, Vance wore a tattered, sweat-stained shirt. Opposing players accused him of using a razor blade to slit the right sleeve of his sweatshirt from the forearm to the wrist in narrow strips. The effect of the fastball coming out of waving strips of flannel was disconcerting to batters, to say the least. When rival hitters claimed that he had cut the shirt on purpose, Dazzy denied the charge. He said it got that way only because it was wearing out. If so, one opponent said, Vance should buy a new shirt. “Oh, no!” Dazzy responded. “This is my lucky shirt. I’ve had it since I was in New Orleans, and I ain’t even washed it.”9

John McGraw, feisty manager of the New York Giants, complained to John Heydler, president of the National League. The prexy could find nothing in the rulebook against tattered shirts, so Vance continued wearing the offending garment. And he continued winning. During the first game of a doubleheader on September 13, 1925, he pitched a no-hitter against the Phillies. Dazzy pitched well for the Dodgers throughout the 1920s, although he never again matched that fabulous 1924 season. In 1925 he led the league in wins, shutouts, and strikeouts. He had a down year in 1926, but still led the circuit in punchouts. In 1927 he was tops in complete games and strikeouts. His last 20-win season came in 1928, when he won the ERA title, as well as leading in shutouts and strikeouts for the seventh consecutive season. The last year in which he was a league leader was 1930, when he topped the circuit in ERA and shutouts. In 1932, the 41-year-old Vance won 12 games, the 10th time in 11 years in Flatbush that he had posted double-digit wins.)

To the chagrin of many of his Brooklyn fans, the Dodgers traded Vance to the St. Louis Cardinals before the start of the 1933 season. At the age of 42 the Dazzler was not quite so dazzling as in days of yore, and he managed to win only six games for the Redbirds. During the offseason he was claimed off waivers by the Cincinnati Reds, but was used sparingly in the Queen City, posting no victories before returning to St. Louis via the waiver route in midseason. The Gas House Gang won the 1934 pennant, giving the Dazzler his first shot at October glory. For the first time in his long and distinguished career, Vance appeared in a World Series that fall. He got into one game, pitched 1⅓ allowed two hits and no earned runs, and struck out three Detroit Tigers.

The Cardinals released Vance in the spring of 1935. The veteran was signed as a free agent by his erstwhile longtime employer, the Brooklyn Dodgers. Used exclusively in relief by the Dodgers, Dazzy posted a three-win, two-loss record in his farewell season. Fittingly, he ended his career with the team with which he had enjoyed his finest years. The right-hander made his final appearance at Ebbets Field on August 14, 1935, in the second game of a Sunday doubleheader against the Chicago Cubs, replacing knuckleballer Dutch Leonard in the lineup. After Brooklyn had taken a 3-2 lead in the bottom of the seventh, Leonard was lifted for a pinch-hitter. Vance came in to begin the top of the eighth and nearly blew the lead. He faced only two batters and put both of them on base. Gabby Hartnett led off the top of the inning with a pinch-hit single. Augie Galan was up next, and Dazzy hit him with a pitch. That was the last hurrah for Vance. Bobby Reis came in and put out the fire, saving the game for Leonard and the Dodgers. Under the peculiar scoring system in use today, Vance would have received credit for a hold. Although he put two men on base, neither of them scored, and the Dodgers held the lead; thus, a hold.

Dazzy Vance retired at the age of 44 with 197 major-league wins. Including 133 victories in the minors, he had won 330 professional games in 26 years.

In the mid-1920s Vance had moved his family to Homosassa Springs, Florida, on the Gulf Coast about 100 miles north of the Dodgers’ spring training camp in Clearwater. The family loved the area, and Dazzy spent his offseasons hunting and fishing in the vicinity. Immediately upon retirement he opened a hunting and fishing camp nearby. Later he operated a Homosassa Springs hotel for sportsmen. He spent his latter years boosting tourism for the area and guiding visitors on hunting and fishing trips.

In 1955 Dazzy Vance received baseball’s highest honor, election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Vance learned of the honor in a telephone call from Walter O’Malley, president of the Dodgers, but he suspected he had been selected when a Florida highway patrolman flagged down his car and told him a photographer was waiting at his house.10 He was very appreciative of the honor. Later he said, “It’s a great thing to happen to you, but I still can’t believe it’s true.”11 Appropriately, his plaque depicted him wearing a Brooklyn cap. The wording on the plaque summarized his career nicely: “Arthur Charles (Dazzy) Vance. First pitcher in N.L. to lead in strikeouts for 7 straight years, 1922 to 1928. Led league with 28 victories in 1924; 22 in 1925. Won 15 straight in 1924. Pitched no-hit game against Phillies, 1925. Most Valuable Player N.L. 1924.” Those words describe Dazzy the ballplayer, but no plaque can capture the essence of the man.

Dazzy Vance died of a heart attack in Homosassa Springs on February 16, 1961, just two weeks before his 70th birthday. His death was a surprise. An outdoorsman, he had remained physically active and seemingly fit to the very end. Although complaining of occasional tiredness, he had been in reasonably good health and actually had played in an old-timer’s baseball game in St. Petersburg just a month before his death.

When informed of the pitcher’s demise, Hall of Fame manager Casey Stengel said: “ I hit against Dazzy when I was with the Giants from 1921 to 1923 and I can say he was a great one. I recall a four-game series between the Giants and the Dodgers when Vance struck out 11 men in one game and 14 in another. I’ll always remember his getting out there on the mound with his shirt flapping. It used to bother the opposing hitters, but it wasn’t the undershirt that made them swing and miss like they claimed, but the stuff he had on the ball.” He added that Vance was “a pleasant man with a good disposition, a fellow you liked to be with and have around.”12 The Ol’ Perfessor may have misremembered some of the details, but he got one thing right. Vance was a great one.

Charles Arthur Vance was survived by his wife, Edythe. He was buried in Stage Stand Cemetery, in Citrus County, just outside Homosassa Springs.

An updated version of this biography is included in “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles F. Faber.

Sources

Graham, Frank, The Brooklyn Dodgers: An Informal History (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945).

James, Bill, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001).

Kavanagh, Jack, and Norman Macht, Uncle Robbie (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1999).

Notes

1 There is disagreement about the order of Vance’s given names. The US Censuses for both 1900 and 1910 list him as Charles A. Vance. When he registered for the World War I draft in 1917 he gave his name as Arthur Charles Vance. It is listed that way in the 1920 census and in the Florida death index. Modern references are almost evenly divided between Charles Arthur and Arthur Charles. At least two sources inexplicably identify him as Clarence Arthur Vance. The most likely explanation seems to be that he was named Charles Arthur, but as a teenager preferred the name Arthur, so changed the order of the names.

2 Fred Lieb, “Dazzy Vance, Hall of Fame Pitching Star, Dies at 69,” in thedeadballera.com.

3 Kavanagh and Macht, 132.

4 James, 869.

5 Lieb.

6 Graham, 87.

7 Graham, 102-03.

8 Graham, 98.

9 Kavanagh and Macht, 133

10 Associated Press account printed in many newspapers; including The Bee (Danville, Virginia), January 27, 1955. Retrieved from newspaperarchive.com.

11 Sheboygan Press, February 18, 1961.

12 Ibid.

Full Name

Charles Arthur Vance

Born

March 4, 1891 at Orient, IA (USA)

Died

February 16, 1961 at Homosassa Springs, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.