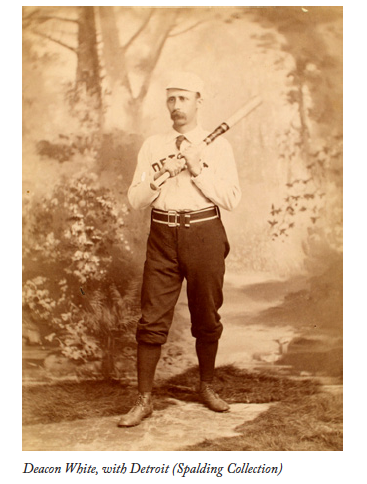

Deacon White

Deacon White was a baseball pioneer. He caught baseball fever after the Civil War and played until the 1890s. His baseball career spanned the end of the amateur era and the start of professionalism, the establishment and demise of the National Association, the founding of the National League, and a players’ revolt that led to the creation of the Players’ League. He was the best catcher in baseball when the most important players in the game were catchers. He played for six championship teams and was a two-time batting champion. He was well respected by teammates, opponents, writers, and fans. History pushed White aside for many decades until he was finally elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame on December 3, 2012, solidifying his place as a baseball legend.

Deacon White was a baseball pioneer. He caught baseball fever after the Civil War and played until the 1890s. His baseball career spanned the end of the amateur era and the start of professionalism, the establishment and demise of the National Association, the founding of the National League, and a players’ revolt that led to the creation of the Players’ League. He was the best catcher in baseball when the most important players in the game were catchers. He played for six championship teams and was a two-time batting champion. He was well respected by teammates, opponents, writers, and fans. History pushed White aside for many decades until he was finally elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame on December 3, 2012, solidifying his place as a baseball legend.

James Laurie White was born on December 2, 1847, in the rural town of Caton, New York.1 The Steuben County town, west of Elmira and a few miles from the Pennsylvania border, was the home to roughly 1,000 residents at the time of his birth. Jim was the son of Lester S. and Adeline (Hurd) White. Lester was a farmer born in nearby Tompkins County around 1820. Adeline was a Caton native born around 1823. The family was of English stock but Jim’s grandparents were born in America.2

Jim was second-born, with an older brother, and six younger siblings. Living nearby were Lester’s brother Benjamin and his family, including future ballplayer Willard Elmer White.

Prior to the start of the Civil War, baseball was largely a city-based sport. The widespread growth of the game didn’t come until after the Civil War and a popular view was that returning soldiers taught rural folks the new game of baseball that they learned during the war. This is exactly what a 91-year-old Jim White stated a few weeks before his death in an interview with The Sporting News. “I learned to play ball from a Union soldier … in 1865, and taught the boys the new game of baseball they had played in the Civil War.”3 If this is the case, it is quite possible the soldier who taught him the game was his older brother, LeRoy, who joined the Union cause in September 1864 and returned home the following year.4

In 1866 Jim helped form a team in Caton. The next year he and LeRoy joined the Monitor Base Ball Club of Corning. On August 8, 1867, the Monitors played in Hornellsville against the Ellicotts of Jamestown for the championship of the Southern Tier of New York counties. Jim played catcher and LeRoy was the left fielder. In the third inning, LeRoy took over as pitcher with a 13-6 lead, forming an all-brother battery. In the end, Jamestown defeated Corning, 23-21. A summary of the game included the following statement: “The Monitors are weak in their short-stop, catcher and in general fielding.” Jim’s day behind the batter may not have been his best; he had seven passed balls. Still, Jim White must have been a pretty good player because the following year he made his way to Cleveland to work and play semipro baseball.5

The Forest City Base Ball Club of Cleveland, comprising mostly local players, was formed in August 1865, becoming the city’s first established team. Jim and LeRoy joined the team in 1868. Jim White, 5-feet-11 and around 175 pounds, instantly became the team’s best player.6

White’s first game in Cleveland was on June 4 against the local Railway Union Club. Forest City lost 21-14 as Jim played shortstop and LeRoy pitched. In Jim’s first at-bat, he “put up an easy one” to the pitcher which was “gracefully accepted.” The Cleveland Daily Leader was impressed with the new player: “While we say that the playing was good on both sides, we would like to make special mention of the play of J. White, the shortstop for the Forest City Club. His record at the bat is very good, but his fielding is better.”7

On July 25 both Jim and LeRoy hit home runs and scored six times each in a 59-25 trouncing of the Railways in LeRoy’s last game with the club.8

On July 31 Forest City lost to the Unions of Morrisania; White started the game at shortstop, moved to catcher, and then pitched. The Leader wrote, “White played very prettily and well in the position of catcher. He is quick and throws swiftly and with precision.” Comments followed on his pitching: “White pitches a swift ball, much swifter than it looks to be, but he needs to practice to pitch the ball where he wants it.”9

At season’s end, Forest City’s record was 11-11-1. White played in all 23 games, leading the team with 73 runs scored while hitting at least seven home runs. He split his time between shortstop and catcher, with at least three pitching performances.10

White did not play with Forest City the first half of the 1869 season. There were inaccurate reports that he played for the Central City Base Ball Club of Syracuse.11 It can be surmised that he had simply left the team and gone home to New York to farm. This could have been his first “retirement” from the game, something he would become known for in coming years.

White returned to the club in August and took over catching duties.12 A month later, Forest City played Central City in Syracuse on September 14, winning 39-11. White stroked four hits and scored four runs for Forest City. The Syracuse Daily Standard wrote, “[A]s for White, their catcher, we think we never saw a better.”13

The 1869 Forest City Club showed tremendous improvement over the 1868 team. The added professionals helped the team double its win total while losing only six games to some of the best teams in the country. After rejoining the team, White played in at least 15 games, mostly behind the batter with the occasional pitching relief appearance.

The battery of Al Pratt and White proved to be among the best in the game, and other teams and spectators took notice. After the “Blue Stockings” defeated the Niagara Club of Buffalo on September 16, a Buffalo paper praised the men: “The specialty in the playing of the Cleveland club, is that of the pitcher and catcher. We have seldom seen these positions played more harmoniously.”14

White had signed in November to play for Forest City in 1870 but rumors as late as March claimed he also signed with the White Stockings of Chicago.15

White stayed in Cleveland. One of his new teammates on the now completely professional nine was Ezra Sutton, a 20-year-old third baseman who had played for the Alert Club of Rochester, New York, in 1869. Sutton would challenge White as the top hitter on the club.

In the season’s first game, Forest City pounded the Eurekas of East Cleveland, 86-6, with White hitting two home runs and scoring 13 runs.16 After a victory against Oberlin, Forest City played two losing games against the undefeated Cincinnati Red Stockings, then followed with wins in their next six games, including a 46-5 defeat of the junior club Eastern Rocks, who gave up three homers to White.17 The win streak ended on May 31 with a loss to the still undefeated Red Stockings.

When the Forest City Club of Rockford came to town in mid-June, the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported, “White, the catcher, had a very bad hand, so bad that he was forced to wear buckskin gloves, yet he played superbly.”18 Al Pratt later reminisced that the barehanded catcher’s hands began to turn black and blue so he wore gloves.19 White wasn’t the first catcher to wear gloves in a game but this instance is notable.

In the second game against the “Green Stockings,” White’s hands were badly sore so he switched to pitcher in the fourth inning with Sutton as his catcher. The Plain Dealer wrote, “White is probably the swiftest pitcher in the world,” and used one play to illustrate his speed as a pitcher: “An idea of the swiftness of his delivery may be obtained from the fact that during this inning, while Sutton was close behind the bat, the striker tipped the ball, which glanced upward, struck Sutton squarely on the forehead just over the left eye, and rebounded with such force that White caught it on the first bound in the pitcher’s box and put the striker out.”20

In mid-June Jim’s first cousin, Elmer White, was brought in to be the change catcher and play right field, debuting on July 21 versus the Eastern Rocks.21

In August, the club went on an Eastern tour with White splitting time at catcher and pitcher. On the 11th he pitched the club to a 26-5 victory over the Niagaras of Buffalo with Elmer as his backstop. The next day he hit a clean homer while pitching the Forest Citys to a 29-2 win over Flower City of Rochester. After three games behind the batter and three losses, White returned to pitch a 13-0 gem on August 18 against the Eckfords of Brooklyn.22

The 1870 season was White’s breakout year. He led the team with 184 total bases and finished second to Sutton with 108 hits while pitching 74 innings with the team’s best average of 1.06 runs per inning.23 The Clipper wrote, “[W]e never saw a catcher so quick and expert in his movements behind the bat. … A cat after a mouse is not quicker than James is after a foul ball. … [H]e is fearless of the hottest balls. … White is what Creighton was – a natural ball player.”24

On April 24, 1871, White married Marium Van Arsdale of Caton. The newlyweds arrived in Cleveland the next day to get ready for the first season of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players, which formed on March 17 in New York City.25 Forest City became a charter member of the first professional league when it paid its $10 entry fee.

The Forest City club traveled to Indiana to play in the first game of the new league against the Kekiongas of Fort Wayne on May 4. Pitching for the Kekiongas was 19-year-old Bobby Mathews. White led off the game and stroked a double, thus getting both the first hit and first double in professional league history. He then became part of the first double play when he didn’t get back to second after a Gene Kimball fly out to second baseman Tom Carey, who touched the base. Mathews threw a four-hit shutout, outdueling Pratt 2-0 in a game that was “unpreceded in the annals of base ball.”26 Jim White led all hitters with two hits. Elmer played right field and struck out three times.

The Opening Day loss was a good indication of what was coming for the team. Forest City also lost its home opener on May 11 despite White hitting his first league homer.

On June 22 Elmer broke his left arm in the first inning of a game after falling down trying to get a foul ball.27 He was out until August 30.

Forest City finished the season 10-19 in seventh place. White caught all 29 league games while batting .322 for the season. He was tied for the most games caught in the NA and led the league in putouts.

Before the 1872 season, tragedy struck the White family. Elmer died, likely of tuberculosis, on March 17 in Scio, New York.28 The 22-year-old became the first professional league player in baseball history to die.29

The Forest City club began the season on May 14 in Washington. White led a 19-hit attack against the Nationals with four hits as Rynie Wolters pitched a complete-game 13-10 victory, but the team was 5-12 until July 6, when it clobbered the woeful Eckfords, 24-5. White, playing left field, had a huge day with four hits and five runs scored. However, after two more losses, the Forest City Base Ball Association canceled the contracts with the players. A compromise was made between the officers of the association and the players that allowed the players to form a co-operative club, keep the same team name, finish out the championship season, play on the old association grounds and split the gate receipts among themselves. White was named captain and manager.30 But in mid-August, the team disbanded.31

White played in all 22 games for the 6-16 Forest City club in 1872, batting .339 with the league’s sixth-best on-base percentage (.363). The Clipper said he didn’t distinguished himself as he did in the previous two seasons as a catcher but passed the blame off on his supporting cast: “[N]o catcher can play with the ability his skill and experience warrant unless he works with a supporting team in the field, willing and able to back up his own strenuous exertions to win.” The paper also commented on White’s character: “We have never known him to growl at an umpire, and his record for integrity is untarnished by even a suspicion.”32 The foundation for White’s famous nickname had begun to be laid.

Despite being one of the top players in the country, White decided to retire from the game. The Boston Red Stockings sent a director of the club to his home to pry him out of retirement. He was reportedly retained but had not reported when play began. In a letter to the Clipper on April 11, captain Harry Wright said, “James White has not arrived. He has been converted [to religion], and thinks at present that he would not be doing right if he should play baseball.”33 Philadelphia’s Sunday Dispatch was less polite in its description of White’s absence: “Mr. James White, who was engaged for the Boston Club, evidently does not think it wicked to break a contract and seriously inconvenience that organization by doing so at the last moment. It seems that James has “got religion,” and thinks … [that playing ball would] jeopardize his future happiness.”34

In fact, White reported on April 19, having “very properly concluded that a man can play ball in a reputable professional nine despite the fact of a recent conversion to religion.”35 White made his debut against Harvard the next day.36

The 1872 Boston championship team was in need of a catcher after Baltimore scooped up Cal McVey during the offseason. White’s signing was even more important. Before he reported, the Red Stockings were left with weak-hitting backup Dave Birdsall or an inexperienced Jim O’Rourke. The season started in Boston on April 23 with an 8-5 loss to the White Stockings of Philadelphia. The club said in a letter to the Clipper: “James White will not be in good condition for a week yet, but he played his position finely.”37

White joined a team stocked with talent: Ross Barnes at second, George Wright at short, Andy Leonard in the outfield, and Al Spalding as the pitcher. The team played well and was in a three-way race for second place, behind the White Stockings.

While Boston was fighting to get back into the championship hunt, the Clipper reported on September 6 that McVey would catch for Boston in 1874 and that “Jim White is as yet undecided about playing, but in case he should remain he will play right-field and change-catcher.”38 The Red Stockings closed the gap and defeated Philadelphia 18-7 on October 2 to take possession of first place. The win gave both teams 34 wins for the season with Boston having two fewer losses and one tie. Philadelphia went 2-2 the rest of the season while Boston played 12 games, winning nine, to capture the pennant.

Jim White had an outstanding season, leading the league in games played (tied with 60) and RBIs (77). He batted .392 and slugged .508, both good for third. On defense, he led all catchers in games played and putouts, and was tied in double plays. The Clipper named him the top catcher for 1873 and once again praised his character: “[H]e stands A No. 1 as a thoroughly honest and reliable player, and he is one whose daily habits of life show that his honesty is not simply policy, but a principle inherent in the man.”39

White returned to Boston in 1874 for a salary of $1,800, the same as Barnes, Spalding, and both Wrights.40 He played right field and was the change catcher before taking over full-time behind the batter on May 13, with McVey moving to right field for most of the season.

The Red Stockings finished the first half of the season with a 30-8 record; the Athletics were second at 23-10. The Athletics beat Boston on July 15 in Philadelphia, and the next day both teams boarded the American Line steamer Ohio and headed for England to play ball. White passed up the trip due to the “express wish of his family.”41 Harvard player John F. Kent took White’s spot on the tour. When the teams returned to Philadelphia on September 9, White was on the dock among the crowd to greet his teammates.42 On September 22 the Mutuals moved one win ahead of Boston and remained neck-and-neck with the Red Stockings until Boston started to pull away on October 14. Boston ended the season with 10 more wins than the Mutuals and once again was the champion.

The Clipper rated “honest Jim White” as the best catcher in 1874, calling him “agile in his movements as a cat, and as plucky withal as a bulldog.”43 He once again led the league in games caught while finishing second in putouts. At the plate he batted .301 and was a top-10 hitter in many offensive categories, including tied for second with three homers. The Clipper article pointed out White’s style of barehanded catching as “yielding to the ball in catching it” by using a “spring-like movement” instead of letting the ball hit the hands at full force to stop it.44

Boston opened the 1875 NA season on April 19 with a 6-0 win over New Haven, grabbing first place from the start with no looking back. The team was primed to win a fourth championship in a row, starting the season 26-0. White injured a thumb on June 3 so switched to right field, with McVey moving to catcher. The Red Stockings’ first loss was to the St. Louis Browns, 5-4, on June 5, with White not in the lineup. The Clipper attributed the loss to the “ill-luck” of losing White: “Now, McVey is a fine catcher, but he is not Jim White, for James stands alone; and when Spalding found that he had not Old Reliable behind the bat, he began to feel less confident as to results; and finally, when the Reds came to play their second match with the St. Louis nine, things were not as they were before.”45 White returned to the lineup the next game and had five hits as Boston soundly beat the Browns, 15-2.46

On July 10 Boston’s “Big Four” of Barnes, McVey, Spalding, and White, met with the management of the Chicago club and agreed to play for the “fancy” prices the Boston club would not offer.47 As the team dined in Taunton, Massachusetts, 10 days later, McVey said he was not playing in Boston next season. Harry Wright took it as a joke but discussed it with White after the meal. White admitted that the “Big Four” agreed to play for Chicago next season.48 In a letter to the Boston Herald, White said he had met with the president of the Boston club, N.T. Apollonio, a month earlier before the team’s Western trip and that Apollonio told him the Red Stockings could not compete with the “fancy Western prices” he might be offered on the trip. White promised he wouldn’t accept any offers on that trip, but did admit to accepting Chicago’s offer when they were in Boston and said he didn’t want to force Boston to increase its offer.49

Spalding was the first to accept Chicago’s offer, agreeing to be the team’s captain and to recruit the others. The Clipper was quite harsh: “The spirit of the Association laws on the subject of engaging players for the ensuing season is that no club-manager or agent shall approach players to negotiate for their services for the next year until the close of the present season.”50

Despite the news, Boston continued to play outstanding ball. After a 15-3 victory over the Athletics of Philadelphia on October 11, the team was 16 wins ahead of the second-place Athletics. The next day Boston played the Lynn Live Oaks. Jim faced brother Will White and got a couple of hits in the game as Boston won, 14-12.51

Eleven days later, after finishing the season series with Chicago in Boston, the teams’ putative 1876 squads faced each other. The “Big Four” joined the Chicago players on the field and defeated the rest of the Boston club, 14-0. The Clipper said the crowd was one of the largest of the season. McVey pitched while Spalding played left field. White scored three runs and had eight putouts as catcher.52

At season’s end Boston was 71-8-3, with 17 more victories than second-place Hartford. White led the league with a .367 batting average, finished second in on-base percentage (.372) and doubles (23), and was third in hits (136). On defense he led all catchers in putouts and assists. He was given a silver water pitcher after the season that was inscribed “Won by Jim White as most valuable player to Boston team, 1875.”53

William Hulbert, president of the Chicago club, set up a meeting at the Grand Central Hotel in New York City on February 2, 1876, with representatives of seven other clubs. The meeting led to the formation of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs. Hulbert’s signing of the “Big Four” and Cap Anson from the Athletics was a violation of the NA’s rules, and the players potentially could have faced expulsion from the league. The formation of the new league eliminated that possibility.

White arrived in Chicago in early April. He brought along his brother Elmer, who went by the nickname Melvin, to take care of the team’s grounds. As for Will, he joined the Cricket Base Ball Club of Binghamton, New York, for the 1876 season.54 On April 25 Chicago played its first NL game against Louisville, winning 4-0. White caught and had one hit. Chicago had some competition during the year from Hartford and St. Louis but was in first place most of the season.

In one notable game, on July 22, White pitched for the first time in many years. Chicago beat up Louisville 30-7, and White pitched the last two innings just for fun. He gave up one hit, struck out three batters, and didn’t allow a run.55

White’s play on the field in 1876 showed he had little trouble adapting to his new team. He was once again the best catcher in the game playing for another championship. He led the league with 60 RBIs. He batted .343 and finished fourth in runs while leading all catchers in games caught for the fifth time. The team finished 52-14, winning the championship, and beating Boston nine out of 10 games.

After the season, both Jim and Will signed with Boston. On April 2, 1877, Jim, Will, and Melvin left for Boston. Melvin was to be responsible for the Boston ball grounds.56 Jim’s role was to split time at first base and the outfield with occasional appearances as catcher. The team also added Hartford’s 31-game winner of the previous season, Tommy Bond, and Jim’s former Cleveland teammate Ezra Sutton.

White’s return to Boston ended a four-year period of dominance by the best battery in the game. From 1873 to 1876, Spalding won 194 games while losing only 47. White was behind the plate for most of Spalding’s games. Without White, Spalding would start and win only one more game as a pitcher.

After a victory on July 18, Boston was 19-10-1, with two more wins than the St. Louis Brown Stockings. On July 20 Will made his major-league debut, against the Red Stockings in Cincinnati. Jim caught his younger brother; thus forming the first all-brother battery in major-league history. Will pitched the first seven innings before Bond came in from center field to relieve the 22-year-old. Jim White was praised by the Cincinnati Daily Gazette: “His stops of wild balls were fairly marvelous, and evoked constant applause from the crowd.”57 But Cincinnati won with Will suffering the loss.

In its last 21 league games, Boston went 20-1, including two wins by Will, one a 14-0 shutout over Cincinnati. For the season, Boston (42-18) had seven more wins than Louisville (35-25). Jim had played for a championship team in five straight seasons. If an MVP award were given out for the 1877 season, White would have easily won it. He finished first in batting average (.387), hits (103), triples (11), extra-base hits (27), RBIs (49), total bases (145), slugging (.545), and OPS (.950). The decision to limit White’s use as catcher saved his hands so Boston could take advantage of his heavy hitting.

Rumors began to emerge in November that the White brothers would sign with Cincinnati for 1878. The death of Jim’s father-in-law on November 20 left him another valuable farm, and he said he knew he should give up ballplaying to tend to his farms, horses, and cattle but that he had a strong fascination with the national game.58 Once referred to as a silver-tongued orator, White was starting to be called “The Deacon” by his peers.59

Jim and Will White joined a Cincinnati team that also included sluggers Charley Jones, Lip Pike, and rookie King Kelly, who would catch a quarter of the games during the season, allowing Deacon a break.

With Deacon batting cleanup, the team started the season 6-0 and was 15-5 after its first 20 games, but succumbed to Boston for the NL championship. The Reds won 10 of their last 11 league games and were declared the champs of the West by the Clipper after “their brilliant rally under the Brothers White during their September matches.”60 The team finished second with a 37-23-1 record, four wins behind Boston.

Hopes were high for the Reds in 1879. The Clipper said the Whites “have proved themselves to be the equals of the best catching and pitching pair who have ever played in a league nine together.”61 Deacon was named manager and captain.

Despite a 5-0 start, the team stumbled. After 18 games and a 9-9 record, White resigned his captaincy. The Clipper wrote that he gave up managing the team because he was being used as a “catspaw” by team president J. Wayne Neff. White said he had “accepted the management and captaincy with the agreement that he was to have sole control” of the club. White was told to read a threatening note to his players but refused. The team was demoralized.62

The team struggled under new manager Cal McVey a good portion of the season but did manage to win more games than it lost. White finished the season with a .330 batting average, 110 hits, and 52 RBIs, all fifth best in the league. He was among leaders in several defensive categories as a catcher but his days as the primary catcher of a team had come to an end. In the years to come, White would primarily start elsewhere on the field. He closed out the 1870s with the most games caught, 409. At the plate he ranked second in hits (846) and RBIs (422), third in total bases (1,069), fourth in on-base percentage (.358), and fifth in games (525), runs (504), and batting average (.345).63 White was easily the premier catcher of the decade. Historian Peter Morris said, “The good catchers of the 1870s were few: Deacon White was far and away the best, because he alone was a standout in the field and at the bat.”64

Though White had declared 1879 as his last season, he was persuaded to sign with Cincinnati for 1880. His wife became ill, and his father died in late July. It wasn’t until August 6 that Deacon appeared in his first game, playing right field at Troy, which happened to be Tim Keefe’s first major-league game and first victory. Keefe held White hitless.65 The season did not end well when White found out he had been fined $10 by manager John Clapp for not going to third in a game against Buffalo on September 27. The team had deducted it from his paycheck without telling him. Deacon followed with a $55 claim for traveling expenses for his wife that he said he was promised. The claim was denied.66

Cincinnati finished the 1880 season last in the National League with a 21-59-3 record. Deacon did not play catcher and hit .298 in 35 games, breaking a string of nine straight seasons batting over .300. His time in Cincinnati officially came to an end when the team was kicked out of the league for playing Sunday games and selling alcoholic beverages at games.

Deacon signed with Buffalo for the 1881 season. The 33-year-old played almost every day but was used as a utility man, playing primarily at first, second, and the outfield. The next season he shifted to third and remained there for most of the rest of his career, although he was the change catcher during the 1882 and 1883 seasons. On May 16, 1884, White set a record by having 11 assists in a nine-inning game while playing third.67

As a batter, Deacon was no longer the hitter he was in the 1870s, but he was still solid. In 1881 he batted .310 and was fourth in RBIs. After two below-.300 seasons in 1882 and 1883, White had a renaissance year in 1884, batting .325 and finishing in the top 10 in many offensive categories.

White and his wife, Marium, had a daughter, Grace Hughson White, on September 8, 1882. It was written that her favorite play object when she was 8 months old was a NL regulation baseball.68

Deacon’s years in Buffalo included significant developments in baseball. The competing American Association began play in 1882. White’s brother Will joined the Cincinnati Association team and become the league’s best pitcher, going 40-12 while leading his team to the league’s first championship. The reserve clause limit, tying players to teams, was increased from five players to 11 in 1883. The National Agreement between the AA, the NL, and the minor-league Northwestern League led to a peaceful time among the leagues and to the creation of the United States Championship series in 1884, baseball’s first World Series.

Buffalo never won a pennant during White’s tenure. Before the 1885 season he decided to retire once again, for fear that the NL would start allowing Sunday games.69 When the championship season started, however, the third baseman was unexpectedly in the lineup.70

The 1885 club was not competitive, falling to 15-34 by July 10, with poor attendance and deepening financial troubles.71 Rumors that the team would disband emerged and discussions with teams for its players were taking place. Managers from other teams were in Buffalo “bidding for these men in about the same manner that slaves were sold during the rebellion [Civil War].” It was said that Deacon and Dan Brouthers were headed to Baltimore. When the players got word that they were being sold like cattle, they “kicked” and “smashed the whole scheme.”72

Despite the commotion, the team survived. White batted in the fourth spot most of the season and had an outstanding year on defense. The Clipper wrote on August 29: “Jim White has not made an error at third in ten straight games. No one can call the Deacon “old” yet. In batting and fielding he leads them all at third.”73 At season’s end, his .888 fielding percentage was second best among the league’s third basemen.

In September the Detroit Wolverines purchased the Buffalo franchise for $7,000 so they could obtain the “Big Four” of White, Brouthers, Hardy Richardson, and Jack Rowe.74 New York manager Jim Mutrie said he would not let his team play if the Buffalo foursome was on the field for Detroit, calling the transfer an illegal act.75 League President Nick Young agreed and ruled that they could not play for Detroit. He ordered umpire Bob Ferguson to forfeit the game to New York if the quartet played.76 The players did not join Detroit. They also refused an order to rejoin Buffalo, saying they were granted their release by Buffalo and were free to sign with any team for 1886.77 The four embarked on a fishing tour of Lake Erie while Buffalo finished the season with 16 straight losses.78

On October 17 the NL and AA signed a new National Agreement, and also agreed that the foursome were free to contract with any league team but could not sign for more than $2,000. The players were expecting between $3,500 and $4,000 from Detroit.79 On November 19 a special committee composed of John Day, Spalding, and Young ruled that the four players belonged to Detroit. Manager Bill Watkins declared that he signed Brouthers, Richardson, and Rowe that evening and was heading to Corning in the morning to sign White.80

During the 1886 season, Detroit (87-36-3) finished 2½ games behind the White Stockings for the pennant. The true difference was the season series, which Chicago won 11 games to 7. White finished eighth in the NL in RBIs (76) and 10th in hits (142). The Detroit Free Press wrote, “Deacon White has a very refreshing custom of hitting the ball when there are men on bases.”81 White led the league in games played at third with 124 and was still being praised for his defense, with the “agility of a colt [who could] give many of the younger pretentious players pointers.”82

As the 1887 season began, White was now the oldest player in the NL at 39. He was benched on June 7 for poor play, replaced by 26-year-old Billy Shindle.83 He didn’t stay benched for long, and batted .303 for pennant-winning Detroit.

Detroit followed up its NL dominance with a 15-game “World Series” defeat of the American Association’s pennant-winning St. Louis team, winning 10 of 15.84 Deacon hit .207 with eight runs scored in the series. Despite the poor offensive performance, the Clipper wrote, “The veteran “Deacon” White has become an immense favorite in Detroit, especially since the world’s championship series, in which he did such yeoman service.”85 It was White’s sixth championship.

The 1888 championship season saw Detroit finish in fifth place. The Clipper wrote: “Hard luck never before had such a cruel grip on any National League club.”86 The 40-year-old White, however, had an outstanding year. He had a career-high 157 hits, ranking fifth in the league. He finished fifth in RBIs (71), sixth in average (.298), seventh in doubles (22), and ninth in total bases (201) while playing the second-most games at third (125).

On October 16, 1888, Sam Thompson was sent to Philadelphia, Jack Rowe and Pete Conway were sent to Pittsburgh, and White, Charlie Bennett, Dan Brouthers, Charlie Ganzel, and Hardy Richardson were sent to Boston. The Beaneaters agreed on an estimated $30,000 for the five ballplayers.87 The “Big Four” was no more.

White tried unsuccessfully to convince the other four players not to sign with Boston.88 On December 18 White and Jack Rowe purchased a controlling interest in the International Association’s Buffalo Bisons. White was named president of the club and Rowe vice president. Both planned to play for the Bisons.89 The deal sent shock waves throughout the baseball community with White and Rowe being labeled as rebels.

The Detroit franchise would lose the cash it agreed upon with both Boston and Pittsburgh for the players’ services if they didn’t sign. On December 19, speaking with a reporter for the Detroit Free Press, White, asked if he was attempting to break the reserve clause, responded, “Not at all. The reserve rule is all right. It is the bulwark of the national game. What I protest against is the selling of a player without his knowledge or consent. I am quite willing to break up the custom.”90

The players had not yet agreed to terms with the clubs they were released to, so both were still on Detroit’s reserve list. NL President Young ruled that the players still belonged to the league and could not play in Buffalo. The players argued that they signed with Detroit and not the NL. Since Detroit was not going to be in the NL in 1889, the players felt they were free to do as they pleased and play in Buffalo.91

White said, “Our contract states that when a club loses its membership the right to reserve ceases. Detroit has sold its franchise, and I have not yet been transferred, I don’t see what claim the Detroit club has on me.”92 Rowe argued that they were not fighting the reserve rule, instead they “simply object to a defunct club selling us like slaves to some other club regardless of our personal feelings.”93

On March 2, 1889, White moved his family from Detroit to Buffalo with the intention of remaining there.94 However, a few days later, White and Rowe were put on the reserve list for Pittsburgh.95 After a few months of on-and-off negotiations, the players agreed to go to Pittsburgh. They each received $1,250 from their release money, and a salary of $500 per month.96 Deacon exclaimed, “I don’t want a man to sell my carcass without I get half.”97 Will White, Buffalo’s manager and starting pitcher, took over the operations of the club to allow the owners (Jim White and Rowe) to play for Pittsburgh.

White and Rowe played for Pittsburgh, which finished 61-71-2 in fifth place. White batted mostly fourth but hit just .253 in 55 games, the worst average of his career. His Buffalo franchise didn’t fare so well either, finishing seventh in an eight-team league. The season finished in the middle of a baseball war between the NL owners and players that led to the formation of the Players’ League.

In December 1889 the Buffalo Club of the Players’ League was incorporated. Rowe and White were among the incorporators.98 Quickly White and Rowe sold the franchise to “capitalists of (Buffalo)” for over $10,000.99 An initial roster of Buffalo players included White and Rowe. Also listed were Ed Beecher, Dummy Hoy, Connie Mack, and Sam Wise, the nucleus of the Buffalo Brotherhood team.100

Buffalo was not expected to do well. White split time between third base and first base. On July 9 Deacon entered a game against New York in the second inning as a pitcher with Buffalo losing 3-0. He pitched eight innings and allowed 18 hits and 15 runs as the team lost, 18-4.101 He didn’t play for almost two weeks after that outing, which was the last pitching appearance of his major-league career.

Buffalo was losing money and in July the league took control and awarded new players to the team.102 The new players did not make the team any better.

Deacon’s last major-league game came on October 4 against Brooklyn. The Bisons were shut out.103 The League’s weakest hitting crew and worst pitching staff ended the season in last place with a 36-96-2 record, 46½ games out of first. White went 0-for-4 at the plate. It wasn’t a storybook ending to a career that started shortly after the Civil War. He finished his career ranked second all-time in RBIs (988), fourth in games (1,560), plate appearances (6,973), at-bats (6,624), hits (2,067), outs (4,574), and total bases (2,605), seventh in runs (1,140), and ninth in extra-base hits (392) and batting average (.312).104 After the season White was able to get the league to pay the final salaries of the Buffalo players.105 When the Players’ League was no more, so was Deacon’s major-league career.

In June 1891 White signed with Elmira (New York-Pennsylvania League) for around $300 a month to manage, captain, and play catcher for the Gladiators.106 After a few weeks of mixed team success, on July 4, by mutual consent, White left Elmira to retire from the game and go back to Buffalo to “spend the remainder of his days enjoying the fortune of $40,000 which he has accumulated on the diamond.”107 In 10 games with Elmira, Deacon batted .229 with eight singles and no extra-base hits. The team could not afford to pay White for his name alone. It was time to walk away from the game.

Once his playing days were over, White continued to live in Buffalo while maintaining his farm and creamery in Steuben County. He owned a broom factory and livery business in Buffalo and partnered with Will in owning the Buffalo Optical Company. He also continued his spiritual life and in September 1896, White along with his brother-in-law Henry L. Davis and Rev. H.H. Hickok certified the incorporation of the Advent Christian Church of Buffalo.108

White’s brother Will died unexpectedly on August 31, 1911, at the age of 56. He was teaching his 12-year-old niece how to swim and suffered a heart attack and drowned.109

Jim and Marium moved in 1909 to Mendota, Illinois, to be with their daughter, Grace, who was attending Mendota College. Marium died on April 30, 1914 at the age of 62. She was buried in Restland Cemetery in Mendota. Deacon eventually rekindled an old romance with Alice Melissa (Force) Thurber, with whom he had attended Country Day School in Caton. The couple were married on April 10, 1917, in Rochester, New York.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Deacon continued to be involved with the church, worked for his son-in-law’s printing company, listened to major-league baseball games on the radio, and attended games and practices of the Aurora College baseball team. He lived with his daughter and eventually apart from Alice, who moved to New York and then Winston-Salem, North Carolina. She died on August 21, 1944, at the age of 95.

In June 1936 National League President Ford Frick invited White to attend the All-Star Game on July 7 in Boston. Frick wrote: “Yourself, Mr. Tom Bond and Mr. George Wright are, so far as we know, the only surviving players who appeared in the National League at the time of its organization, and we feel that your presence at the All Star game would be a distinction and honor which the National League would much enjoy.”110

It is probable White’s daughter, Grace Watkins, declined on his behalf. Responding to a similar invitation on July 1, she wrote: “Nothing would please Mr. White more than to be able to participate with you in this very interesting celebration. At present Mr. White is quite feeble being nearly 89 years of age and is practically confined to his room. He has always maintained a very great interest in baseball especially in the clubs in which he played. This would have been a great pleasure to him to have accepted your Invitation and had it been a year or two earlier, I believe he would have made the effort to have been with you.”111

Before the National Baseball Hall of Fame election announcement in 1939, The Sporting News wrote: “Plans for the celebration of the centennial of the game at Cooperstown, N.Y., this year would be incomplete if they did not include the installation of a plaque bearing the name of James (Deacon) White, and a special invitation for him to attend the ceremonies as the official representative of the major leagues.”112 When White failed to be elected, the paper wrote: “Baseball passed up a great opportunity to capitalize on sentiment in ignoring this grand old man of the game, now in his 90’s, whose waning years could have been glorified by personally seeing his name inscribed in the Hall of Fame, which is dedicated to the sport he so long adorned.”113

Twenty-five days after the celebration in Cooperstown, Deacon White died of uremic poisoning on July 7, 1939.114 He was said to have been deeply disappointed that he wasn’t elected to the Hall of Fame. He died at his daughter’s summer cottage at Camp Rude on the Fox River near St. Charles, Illinois, north of Aurora.115

White had been the oldest living former major-league ballplayer since George Wright died on August 21, 1937. John McKelvey was slightly more than three months older than White but only played in 1875 before the NL was formed.

Despite White’s passing, the campaign for his election continued for many years, but to no avail.

In December 2008 White received 41.7 percent of the vote from the Veterans Committee, not enough for election. In 2010 the Hall of Fame had revamped the Veterans Committee structure, forming three “era” committees that would rotate each year: Expansion Era (1973-Present), Golden Era (1947-1972), and Pre-Integration Era (Origins-1946). The Pre-Integration Era Committee was third in the rotation and announced its first results on December 3, 2012, electing three new members: Jacob Ruppert, Hank O’Day, and Deacon White. The wait was finally over!

Jerry Watkins, White’s great-grandson, spoke at the induction ceremony on behalf of the family on July 29, 2013.

This biography is included in “Boston’s First Nine: The 1871-75 Boston Red Stockings” (SABR, 2016), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-Reference.com, and Retrosheet.org.

Egan, James M. Base Ball on the Western Reserve: The Early Game in Cleveland and Northeast Ohio, Year by Year and Town by Town, 1865-1900 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008).

Maas, David. Files and Notes. Family Friend of Jerry Watkins, great-grandson of Deacon White.

Morris, Peter. A Game of Inches: The Game Behind the Scenes: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2006).

Morris, Peter. A Game of Inches: The Game on the Field: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2005).

Morris, Peter. Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2009).

Roer, Mike. Orator O’Rourke: The Life of a Baseball Radical (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005).

Seymour, Harold. Baseball: The Early Years (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960).

Spink, Alfred H. The National Game (St. Louis: National Game Publishing Co., 1910).

Notes

1 Though many sources listed his birthdate as December 7, White’s headstone, his Hall of Fame player questionnaire, and other sources list it as December 2. It appears an error was made in the mid-1970s, changing it to December 7, the same birth date as his cousin Willard Elmer White.

2 D.H. Watkins, Letter to Lee Allen, July 23, 1956.

3 Gene Kessler, “Deacon White, Oldest Living Player, at 92 Recalls Highlights of Historic Career That Started in 1868,” The Sporting News, June 22, 1939: 7B.

4 “Aged Civil War Veteran Is Dead: O. LeRoy White Passes Away at 88; Was Professional Baseball Player,” Evening Leader (Corning, New York), February 17, 1934: 12.

5 “Championship of the “Southern Tier!” Jamestown Takes the Belt!” Jamestown (New York) Journal, August 16, 1867: 3.

6 Peter Morris, “Forest City Base Ball Club of Cleveland,” Base Ball Pioneers, 1850-1870: The Clubs and Players Who Spread the Sport Nationwide (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 125-33.

7 “Railway Union Victorious – Champions Beaten – Exciting Game – Interrupted by Rain – Score, Railway, 21; Forest City, 14,” Cleveland Daily Leader, June 5, 1868: 4.

8 “Forest City Victorious,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 27, 1868: 3.

9 “The Unions Still Champions – A Beautifully Played and Most Interesting Game,” Cleveland Daily Leader, August 1, 1868: 4.

10 Marshall D. Wright, The National Association of Base Ball Players, 1857-1870 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 203-04. Home-run and pitching appearance totals from author’s research of daily game accounts.

11 The Cleveland Daily Leader wrote on July 28 of the coming match between Forest City and the Central City Club, “The game will derive additional interest from the fact that James White, the Forest City catcher of last season, now plays that position in the Central City Club.” However, just two days later, the newspaper provided the following: “It turns out that the James White of the Central City club is not the Forest City catcher of last year, but another man of the same name.” The “White” on the Syracuse team was Horatio Stevens White.

12 “Base Ball,” Cleveland Daily Leader, August 2, 1869: 4.

13 “City Items. Base Ball,” Syracuse Daily Standard, September 15, 1869.

14 “Buffalo against Cleveland – The Game Between the Forest Citys and the Niagaras – Score 32 to 22 in Favor of Cleveland,” Evening Courier & Republic (Buffalo), September 17, 1869.

15 “Base Ball,” Cleveland Plain Dealer , March 2, 1870: 3, and March 8, 1870: 3; Cleveland Daily Leader, March 15, 1870: 4.

16 “The Forest City Club of Cleveland,” New York Clipper, May 14, 1870: 43.

17 “The Game Saturday,” Cleveland Daily Leader, May 23, 1870: 4.

18 “The Game Yesterday – Forest City vs. Forest City – Cleveland Wins – Score 21 to 12 – Miscellaneous,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 14, 1870: 3.

19 “An Older Timer. Al Pratt Tells of His Base Ball Career,” The Sporting News , March 23, 1895: 2. Pratt was the pitcher on June 13, 1870. He said the incident took place in 1872; a probable case of misremembering.

20 “The Return Game Between the Two Forest City Clubs – Cleveland Defeated – Score 24 to 18,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 15, 1870: 3.

21 “Base Ball,” Cleveland Daily Leader , July 21, 1870: 1; Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 21, 1870: 3.

22 Gene Kessler, “‘Deacon’ White, 84 Years of Age, Recalls How First Professional Baseball Was Played as Early as 1868,” The Sporting News, November 6, 1930: 7. White recalled, “[M]y windup motion puzzled them,” and gave a demonstration of his delivery: “He twisted his shoulders and zipped his arm in a perfect arch. The knuckles almost touched the floor, but we noticed he had used a stiff arm without bending the wrist, had kept his feet flat and face forward.”

23 Wright, 301-02.

24 “The Professionals of 1870. Review No. 1,” New York Clipper, January 21, 1871: 333.

25 “At Home,” Cleveland Daily Leader, April 26, 1871: 4.

26 “The Finest Game on Record,” New York Clipper, May 13, 1871: 42.

27 “Almost a Defeat – Elmer White Breaks His Left Arm – Game With the Athletics To-day,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 23, 1871: 3.

28 “Died,” Corning (New York) Journal, March 28, 1872: 3.

29 Scio town historian Marlea Robbins, telephone interview, March 15, 2016. Historian Frank Russo was also helpful with his insight into the death of Elmer White.

30 “Amusements. Base Ball,” Cleveland Daily Leader, August 5, 1872: 4.

31 “Funeral of the National Game in Cleveland—The Muffers Disband To-day,” Cleveland Daily Leader , August 20, 1872: 4.

32 “The Players of 1872. The Catchers – No.2,” New York Clipper, December 21, 1872: 301.

33 “The Boston Club Games,” New York Clipper, April 19, 1873: 20.

34 “A Whimsical Freak,” Philadelphia Sunday Dispatch, April 20, 1873.

35 “Baseball. Notes,” New York Clipper, April 26, 1873: 26.

36 “Base Ball,” Boston Herald, April 21, 1873: 4.

37 “Philadelphia vs. Boston,” New York Clipper, May 3, 1873: 34.

38 “Baseball Gossip,” New York Clipper, September 6, 1873: 178.

39 “The Players of 1873,” New York Clipper, February 21, 1874: 373.

40 George V. Tuohey, A History of the Boston Base Ball Club (Boston: M.F. Quinn & Co., 1897), 68.

41 “Short Stops,” New York Clipper, July 25, 1874: 131.

42 William J. Ryczek, Blackguards and Red Stockings: A History of Baseball’s National Association (Wallingford, Connecticut: Colebrook Press, 1999), 165-66.

43 “The Professional Season of 1874. Fourth Article. The Play and the Players,” New York Clipper, December 19, 1874: 299.

44 Ibid.

45 “The Championship Record. Defeat of the Bostons,” New York Clipper, June 12, 1875: 83.

46 “Base Ball,” Daily Evening Traveller (Boston), June 8, 1875: 1.

47 “Boston Baseball Association,” New York Clipper, December 25, 1875: 307.

48 “The Chicago Nine for 1876,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 24, 1875: 2.

49 “Jim White Rises to Explain,” New York Clipper, August 7, 1875: 149.

50 “Breaking-Up the Boston Team,” New York Clipper, July 31, 1875: 139.

51 “Boston vs. Live Oak,” New York Clipper, October 23, 1875: 237.

52 “Chicago, ’76, vs. Boston, ’76,” New York Clipper, October 30, 1875: 242.

53 Gene Kessler, “Deacon Jim White Won First Most Valuable Player Award 55 Years Ago as Boston Star,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1930: 6.

54 “Local Matters,” Addison (New York) Advertiser, May 4, 1876.

55 “The Home Willow-wielders Slaughter Devlin and His Varied Phenomena,” Chicago Daily Inter-Ocean, July 24, 1876: 3.

56 Uri Mulford, Pioneer Days and Later Times in Corning and Vicinity, 1789-1920 (Corning, New York: U. Milford, 1922), 272.

57 “The Cincinnati Red Stockings Victorious Over the Bostons,” Cincinnati Daily Gazette , July 21, 1877: 10.

58 “Base Ball,” Cincinnati Commercial , December 20, 1877: 3.

59 “Baseball. Ball Talk,” New York Clipper , March 9, 1878: 394.

60 “The League Arena,” New York Clipper , September 21, 1878: 202.

61 “The Cincinnati Club,” New York Clipper , November 2, 1878: 253.

62 “The Cincinnati Club,” New York Clipper , June 21, 1879: 101.

63 Baseball-Reference.com Play Index used to calculate 1870s totals.

64 Tim O’Shea, “Peter Morris on His Catcher Book,” Talking with Tim , May 20, 2009, talkingwithtim.com/wordpress/2009/05/20/peter-morris-on-his-catcher-book/ (accessed June 12, 2016).

65 “Troy vs. Cincinnati,” New York Clipper , August 14, 1880: 163.

66 “Later Baseball Notes,” New York Clipper , October 16, 1880: 238.

67 “Philadelphia vs. Buffalo,” New York Clipper , May 24, 1884: 152.

68 “Notes,” Cincinnati Commercial , April 1, 1883: 3.

69 “Sporting Matters,” Detroit Free Press , April 23, 1885: 3.

70 “Detroit vs. Buffalo,” New York Clipper , May 9, 1885: 116.

71 “The Buffalo Club,” New York Clipper , July 18, 1885: 274.

72 “Dots from Other Diamonds,” New Orleans Daily Picayune, July 25, 1885: 8.

73 “Base Hits,” New York Clipper , August 29, 1885: 378.

74 “Bought Another Club. The Detroit Management Purchase the Buffalo Franchise,” Detroit Free Press , September 16, 1885: 8.

75 “A Big Four Puss. The New Yorks Say They Won’t Play if the Buffalo Men Do,” Detroit Free Press , September 19, 1885: 4.

76 “Detroit vs. New York,” New York Clipper , September 26, 1885: 441.

77 “Baseball. The Big Four,” New York Clipper , October 3, 1885: 458.

78 “Base Ball,” Washington Sunday Herald, October 4, 1885: 4.

79 “Detroit’s Heavy Disappointment,” St. Paul Daily Globe , October 21, 1885: 4.

80 “The Big Four Are Ours,” Detroit Free Press , November 20, 1885: 8. Deacon signed a two-year deal for $7,000.

81 “Piling Up Victories. Base Ball. Liners,” Detroit Free Press , June 16, 1886: 5.

82 “Tuesday’s Great Game,” The Sporting News , May 24, 1886: 1.

83 “Detroit vs. Pittsburg,” New York Clipper , June 18, 1887: 217.

84 “Delighted Detroit,” Sporting Life , October 26, 1887: 5.

85 “National League Record,” New York Clipper , November 12, 1887: 559.

86 “An Interesting Review of the Peculiar Situation in the Lake City,” New York Clipper , September 1, 1888: 397-98.

87 “Our Boston Budget. The Deal with Director Stearns for Some of the Detroit Talent,” New York Clipper , October 27, 1888: 530.

88 “Base Ball Notes,” The Times – Philadelphia , November 4, 1888: 14; “Boston’s Ball Schemes,” New York Times , November 12, 1888: 5.

89 “Jack Rowe and Deacon White Surprise the Natives. They Buy Buffalo Out,” Buffalo Courier , December 19, 1888: 3; “Baseball. The Buffalo Deal,” New York Clipper , December 29, 1888: 673.

90 “Boston’s Treachery,” Detroit Free Press , December 20, 1888: 8.

91 “The Buffalo Deal,” New York Clipper , December 29, 1888: 673. See also “Among the Ball Men,” New York Herald , December 21, 1888: 6.

92 “Boston’s Treachery”; “Base Ball News,” The Times – Philadelphia , December 23, 1888; 16.

93 “Stray Sparks from the Diamond,” New York Clipper , January 5, 1889: 689.

94 “‘Deacon’ White’s Settled Plans,” New York Herald , March 4, 1889: 9.

95 “The Base Ball World,” Philadelphia Inquirer , March 11, 1889: 6.

96 “Short Stops,” New York Times , July 4, 1889: 3; Joseph Overfield, “James “Deacon” White,” The Baseball Research Journal 4 (1975): 10.

97 “Jim White Talks Business,” Cleveland Leader and Morning Herald , June 29, 1889: 3.

98 New York Clipper , December 28, 1889: 700.

99 New York Clipper , January 4, 1890: 716; New York Clipper , December 6, 1890: 617.

100 ” New York Clipper , December 28, 1889: 700.

101 “The Players’ League. The Western Clubs Playing Their Second Eastern Series of Games,” New York Clipper , July 19, 1890: 297.

102 “Bracing Up Buffalo. Secretary Brunell Reorganizing the Players’ League Club,” The News (Frederick, Maryland), July 28, 1890: 5; New York Clipper , August 2, 1890: 330.

103 “Players’ League. Buffalo vs. Brooklyn,” New York Clipper , October 11, 1890: 490.

104 Baseball-Reference.com. Play Index used to calculate career totals.

105 “Ward, Hanlon and Irwin Added to the General Conference Committee,” Pittsburgh Post , October 22, 1890: 6.

106 “Six Men Released,” Elmira Daily Gazette and Free Press , June 13, 1891: 8.

107 “Deacon White Has Gone,” Elmira Daily Gazette and Free Press , July 6, 1891: 8.

108 “New Church Incorporated,” Buffalo Courier , September 27, 1896: 11.

109 “Will White, Famous Old Redleg Twirler, Dead at Port Clinton, Ontario,” Cincinnati Enquirer , September 1, 1911: 2; Ruth Holmes McKee, Letter to Lee Allen, September 6, 1962.

110 Ford Frick, Letter to James L. White, June 3, 1936.

111 Grace Watkins, Letter to L.S. MacPhail, July 1, 1936. MacPhail had invited White to a Reds game to celebrate the NL’s 60th anniversary.

112 “An Honor Due Deacon White,” The Sporting News , April 20, 1939: 4.

113 “Six Hits and An Error,” The Sporting News , May 11, 1939: 4.

114 D.H. Watkins, Letter to Lee Allen, July 23, 1956.

115 “James White, 92, Ex-Baseball Star,” New York Times , July 8, 1939: 20.

Full Name

James Laurie White

Born

December 2, 1847 at Caton, NY (USA)

Died

July 7, 1939 at Aurora, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.