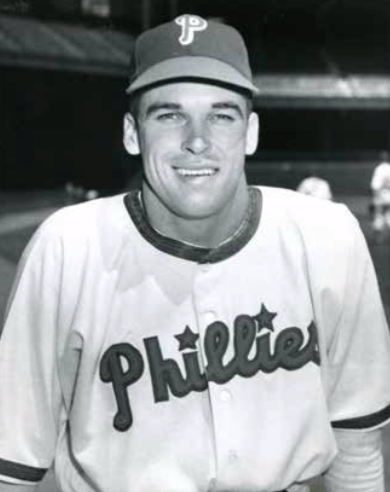

Dick Sisler

Dick Sisler, who hit the most famous home run in Phillies history, came from a baseball family. His older brother, George, played in the minors, later forging a distinguished career as a minor-league executive. Dick’s younger brother, Dave, pitched in the majors. Their father, George Harold Sisler, was a Hall of Famer whose playing accomplishments dwarfed those of Dick during his eight years in the majors. Yet Dick achieved something that eluded his illustrious elder — playing on two pennant winners, one of which, the 1946 Cardinals, won the World Series.

Dick Sisler, who hit the most famous home run in Phillies history, came from a baseball family. His older brother, George, played in the minors, later forging a distinguished career as a minor-league executive. Dick’s younger brother, Dave, pitched in the majors. Their father, George Harold Sisler, was a Hall of Famer whose playing accomplishments dwarfed those of Dick during his eight years in the majors. Yet Dick achieved something that eluded his illustrious elder — playing on two pennant winners, one of which, the 1946 Cardinals, won the World Series.

Richard Allan Sisler was born to George and Kathleen Sisler in St. Louis on November 2, 1920, the second of four children. (Besides the three brothers, there was a sister, Frances.)1 His arrival came on the heels of his father’s tremendous performance for the St. Louis Browns in 1920. The elder Sisler had just won his first batting title with a .407 average, anchored by 257 hits, then a major-league record.2 He was then considered an equal of Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth.

Sisler and his siblings were raised with several themes guiding their upbringing. Love of family and a high respect for integrity was instilled early on. Dave Sisler recalled, “(George Sr.) … had scruples like you wouldn’t believe. All he ever tried to do was pass that on to his kids.”3

Another tenet of the Sislers was a love of education. George Sr. graduated from the University of Michigan with a degree in mechanical engineering. He could have easily become a professional ballplayer, his services were highly sought after, but he chose to pursue an education first and became in his era one of the few college graduates in the major leagues. This dedication to quality education carried over for his children in a practical way. George Sr. joined with others to found the John Burroughs School in St. Louis in 1923. The school was, as the elder Sisler’s biographer commented, “progressive, nonsectarian and college preparatory.” All four children went to Burroughs, and all attended college.4

Sports, especially baseball, dominated conversation. Frances recalled of her brothers, “We’d be sitting around the dinner table and (the elder Sisler would) always be talking baseball with my brothers and I’d get so sick of it.”5 When asked if Sisler Sr. had to coax the boys into playing baseball, their mother, Kathleen, offered, “He didn’t have to. George was such a wonderful father that each of the boys wanted to be like him.”6

Dick’s earliest memories involved time spent in big-league settings. He recalled, “The earliest I remember was when I was out at the ballpark and my Dad of course, was a great ballplayer, and Babe Ruth or Lou Gehrig stopped by the box … to say hello to my mother. That’s the earliest I can remember and that’s a long time ago.”7 Later, when his dad played for the Boston Braves and the Sislers lived in Boston, Dick often went to a nearby drugstore for an ice cream with Rogers Hornsby, who took a shine to him.8

While attending Burroughs, Dick excelled in football, basketball, track, and baseball.9 After graduating, Dick followed his brother George to Colgate University. While George Jr. graduated with a degree and then began a minor-league career, Dick, after less than a year at school, signed a minor-league contract with St. Louis, an act the elder Sisler’s biographer Rick Huhn noted was “probably much to the chagrin” of his parents.10

Sisler spent four years in the minors, working his way through the Cardinals system. It was a daunting experience as he endured taunts from numerous players about not measuring up to his father: “You’ve got to earn your own way in this league. Why don’t you let your dad field for you? Put a glove on your foot,” were among the many comments made.11

Despite being hassled, Sisler played well. During his inaugural season, 1939 with the Washington Redbirds in the Class-D Pennsylvania State Association, Sisler hit .319 and led the league with 16 home runs. Next year, moving up to the Class-C Michigan State League and playing for the Lansing Lancers, Sisler hit .322, pacing the league with 12 triples.

He moved up to the Asheville Tourists in the Piedmont League in 1941, performing reasonably well, batting at a .270 clip. The most significant event for Sisler that year, however, came off the field. While swimming one day he met Asheville resident Dorothy Ann Campbell. They were married on September 18, 1942, beginning a union lasting 56 years. The couple had four children, Kathleen, Shari, Patricia, and Richard.12

Soon after, the draft-eligible Sisler enlisted in the Navy, rising to chief petty officer and serving as a physical instructor at the Bainbridge Naval Training Center in Maryland through World War II.13 Upon his discharge in late 1945, Sisler played winter ball for Havana at the behest of the Cardinals. St. Louis was not high on incumbent first baseman Ray Sanders and wanted to give the 25-year-old Sisler a long look, despite his having played exclusively as an outfielder in the minors.14

He did not disappoint. In his first game for Havana, Sisler hit two home runs. Soon afterward he hit three more, off Sal Maglie. As the season progressed Sisler continued his long-ball exploits, once driving a pitch over a 450-foot fence in Havana. Immensely popular, Sisler became known as “the Babe Ruth of Cuba” and received numerous gifts as well as a gold medal from the president of Cuba.15 He could not go anywhere without attracting large crowds, not to mention the notice of local resident Ernest Hemingway, whose interest in baseball caused him to invite Sisler to a party one evening.

The season ending, Sisler returned to the States, a front-runner to take over first base. Cardinals owner Sam Breadon unloaded Sanders, whose underperformance in 1945 made him expendable.16 Sisler hit over .400 during spring training and opened the season at first for St. Louis, playing his first major-league game on April 16, 1946, against the Pittsburgh Pirates.17 In his first at-bat, Sisler doubled in two runs.

By early June, however, Sisler was hitting in the mid-.260s with but one home run when he injured his hand and was forced out of the lineup for a few days.18 In that brief time he lost his job to Stan Musial, who was shifted from left field to first. Sisler’s injury was not serious but his performance was lacking. Musial’s presence on the infield immeasurably improved the team. Sisler, platooning with others, took over Musial’s spot in left.

St. Louis ended the season tied with Brooklyn and won the first two games of a best-of-three playoff to take the pennant.19 In the World Series the Cardinals bested the Red Sox in seven games. Sisler pinch-hit twice, grounding out both times. Despite his minimal presence, he did play in the Series, something his father never achieved during his 15-year career.

For the season Sisler hit .260 with three home runs, not as well as expected. In 1947 he appeared in just 46 games, 31 as a pinch-hitter. Overall he batted just .203 and became expendable. In early 1948, Sisler was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. The move gave him another chance. “I was hurt when I was traded to the Phillies,” he said. “I had grown up in St. Louis and the Cardinals were my hometown team. And it is hard to leave a ballclub where you know all the guys and go to a new one. But it turned out to be the greatest break in my career.20

Named the Phillies’ Opening Day first baseman, Sisler found his niche, batting .274 with 11 home runs in 121 games. His late-season play was marred when he was forced out of the lineup with a kidney infection.21 Returning to the lineup in mid-September, he finished well and seemed to have a bright future with the Phillies going into 1949.

During the winter, however, Philadelphia acquired first baseman Eddie Waitkus from the Cubs. The rationale for obtaining Waitkus was that he was better defensively than Sisler, who would be shifted to the outfield.22 As the season started, however, Sisler was unable to break into an outfield of Richie Ashburn, Del Ennis, and Bill Nicholson. Through mid-June he was used exclusively as a pinch-hitter. Waitkus, showing superb defensive skills, was batting over .300 and leading All-Star balloting for first base.

But then, on the evening of June 14, 1949, Waitkus was shot by a mentally ill young woman in the Phillies’ Chicago hotel and lost for the season. It was a shocking blow. Philadelphia had just climbed into the first division, a major achievement for a club that had not finished higher than fifth since the 1932 season.

The next morning Phils manager Eddie Sawyer told Sisler he would start at first. Sisler replied, “I’m no Waitkus, Skipper. But I’ll give you all I got.”23 Stepping into the lineup, he played virtually every game from then on. Sisler had been given a second chance on joining the Phillies, now he received another and would not disappoint. In his first game on the field that season, he connected for three hits and scored two runs in a Phillies victory, and went on to hit near .300 in June as the club overcame the loss of Waitkus. Philadelphia eventually finished third, Sisler contributing with a .289 average.

The Phillies were on the rise. At the end of 1945 they had finished last seven out of the previous eight seasons. The team began to change when Bob Carpenter Jr. took over the club. Progress was slow at first but Carpenter, stayed true to a policy of hiring sound baseball talent, principally Herb Pennock as general manager, being willing to spend money on young talent, and expanding the team’s farm-club operations.

Over the next few years players like Ashburn, Ennis, Curt Simmons, and Robin Roberts joined the team. Before Sawyer became manager in 1948, he had directed many of the Phillies while serving as skipper in the Phillies’ minor-league system. When he assumed leadership of the Phillies in July 1948, he knew most of the personnel. The team improved to sixth, then climbed to third in 1949 and became a legitimate contender for the 1950 season.24

Sisler had contributed to this resurgence and felt going into 1950 that he would start at first base. He had done well; moreover there was a question whether Waitkus had fully recovered. Despite these factors, Sawyer decided during spring training to go with Waitkus. Sisler, disgusted, challenged Sawyer: “I can play the outfield better than some of the fellows you have. How about a try?”25 Sawyer assented and for the next several weeks Sisler worked hard to regain his outfield skills, not having played there since 1947 with St. Louis. Over the next several weeks he worked hard on fielding, throwing, and improving his running skills. He hit well, batting .437 during spring exhibition contests.26 The hard work paid off. Sisler started in left as the Phillies thrashed Brooklyn 9-1 at Shibe Park on Opening Day.27

The team did well, based on solid hitting and the best pitching in the league. Robin Roberts and Paul Rogers’ book The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant describes the team’s success as more than statistics. Roberts captured the essence of the club: “The Whiz Kids played hard all game, every game. Our effort to win games was remarkable. We were, for the most part, very young and we appreciated the opportunity to play in the big leagues.” Curt Simmons commented on the sense of camaraderie: “[W]e all got along well and groups of guys would hang out together.”28

A large part of the solid attitude was traced to Sisler. Keeping things loose, Sisler did innocuous things like leading the team in singing, whether in the shower or on a bus. Called the “Big Cat” by his teammates, he was one of the team’s most popular players, helping to ensure that the atmosphere stayed on even keel.29 And this from a man who stuttered.30 While his efforts were vital in keeping things loose, there was also a fierce desire to win. Roberts shared how that attitude pushed the envelope on one occasion.

He recalled losing a close game to Chicago on a home run by Hank Sauer. Trying to wind down after the defeat, he and Sisler were the last players in the clubhouse, taking a shower when Sisler said, “My old man says anytime you let a home run hitter beat you late in the game you are a bad pitcher.” Roberts retorted, “If you hit like your old man, I wouldn’t be in so many close games.” Fisticuffs seemed imminent but Sisler walked away. A few minutes later, Sisler came by with two beers. “That wasn’t called for. We’ve talked enough, haven’t we?” Roberts replied, “Yes we have, Dick.” They drank in silence. 31

While Sisler’s help setting the team’s attitude off the field was vital, he had a career year on the field. By the All-Star break he was hitting .325, and selected as a reserve on the National League All-Star team. Sisler hit a pinch-single in the game, eventually won by the NL in the 14 inning on Red Schoendienst’s home run. Coincidentally, Sisler pinch-hit for Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe; their paths would cross again on the first of October.

By September 21 the Phillies were seven games ahead of the Dodgers. Then the team collapsed as the starting pitching staff was decimated. Curt Simmons (17-8 for the season) had been called to active military duty. Pitchers Bob Miller and Bubba Church were out of action.32 Roberts could not hold things together alone. As Philadelphia slumped, Brooklyn surged. On the last day of the season, Philadelphia was a game ahead of the Dodgers with the final contest to be played in Brooklyn. Roberts, pitching on two days’ rest, faced Newcombe. With an overwhelmed pitching staff, Philadelphia needed a win to avoid a best-of-three playoff against the onrushing Dodgers.

In the top of the 10th with the score tied 1-1, Sawyer allowed Roberts to bat. He had given up just five hits, was still effective, and Sawyer wanted to keep him in the game. Roberts bounced a single up the middle. Waitkus followed with a base hit, putting runners on first and second. Ashburn, bunting, forced Roberts at third, bringing Sisler to bat.

Sisler had entered the game with a heavily taped sprained right wrist. Despite that, he had three singles and had scored the lone Phillies run. On a 1-and-2 pitch, Newcombe tried to pitch inside but it came over the middle of the plate. Despite his injured wrist, Sisler hit the ball to the opposite field just over the left-field fence to give the Phillies a 4-1 lead. His father, then a scout for the Dodgers, watched Dick’s home run with mixed emotions, recalling, “The cameras were on me to get my reactions. I sat with a straight face, with no reactions at all … an actor for the first time in my life.”33 Roberts held the Dodgers scoreless in the bottom of the 10th and Philadelphia had its first pennant since 1915.34

The World Series against the Yankees began three days later. Philadelphia’s pitching staff was in a state of disrepair and the batters were overwhelmed by a Yankees pitching staff that swept to victory in four straight games. Three of the losses came by one run. Philadelphia hit .203, Sisler just 1-for-17. After the Phillies won the pennant on the last day of the season, the World Series proved anticlimactic.

In January 1951, three months after Sisler hit his famed home run, Ernest Hemingway renewed interest in a novella he had conceived in the 1930s. After several years of indifferent work and increasing health problems, he resumed work on the story, initially titled On the Blue Water. It concerned an old Cuban fisherman fighting to land a giant marlin. Hemingway completed it in two months, retitling it The Old Man and the Sea. It was an immediate best-seller, winning Hemingway the 1953 Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1954. It became an American classic.

The old fisherman, Santiago, reminisces about many things with a young boy, his apprentice, Manolin, before going out to sea. Santiago shares his love of baseball, and expresses reverence for Joe DiMaggio. Then he speaks of the National League and Sisler:

“In the other league between Brooklyn and Philadelphia I must take Brooklyn. But I think of Dick Sisler and those great drives in the old park. There was nothing ever like him. He hits the longest ball I have ever seen.

“Do you remember when he used to come to the Terrace? I wanted to take him fishing, but I was too timid to ask him. Then I asked you to ask him and you were too timid.

“I know. He might have gone with us. Then we would have that for all our lives.”

Hemingway was referring to the 1950 pennant race and Sisler’s play in Cuba during the winter of 1945-46. Sisler commented that he had read the book several times and said, “Strange. He talks about me the same way he talks about DiMaggio.”35 Sisler had become immortalized in print.

The 1950 season proved to be Sisler’s finest. He hit .296 with 13 homes runs and 83 RBIs. From then on the fortunes of both Philadelphia and Sisler declined. In 1951 the club fell to fifth, the loss of Simmons for the year and offseasons for others generating the poor finish. Philadelphia gradually drifted to the lower echelons of the league, with the failure to obtain new prospects and tardiness in recruiting African Americans major factors in their decline. 36

Sisler hit .287 in 1951 with less power than in 1950. After the season he was traded to Cincinnati, his stay with the Reds lasting one month into 1952, when he was dealt to the Cardinals. Sisler did passably well for St. Louis, batting .261, but he was not in their plans for the future. In 1953 they brought up minor-league sensation Steve Bilko and made him their first baseman. There were no more chances — Sisler lasted until August, when he was sold to the Columbus Red Birds in the American Association.37 His eight-year career in the majors included a .276 average, 55 home runs, and 360 RBIs. He played on two pennant winners, one of which won the World Series.

Sisler played six more years in the minors with various clubs, along the way posting several .300-plus marks before hanging up his spikes while managing the Nashville Volunteers, a Cincinnati farm team, in 1957.38 In 1960 Sisler was promoted to manager of the Triple-A Seattle Rainiers.

When the 1960 season ended, Cincinnati batting coach Wally Moses moved to the Yankees organization.39 At the request of Reds manager Fred Hutchinson, Sisler was named to replace Moses. Sisler’s timing was excellent — the Reds won the 1961 pennant and Sisler picked up $5.356.37 as a World Series share.40

Sisler continued with the Reds the next several years. In 1962 his brother Dave joined Cincinnati as a reliever in what would be his final season in the majors. Older brother George, the general manager of the Rochester Red Wings, that year received The Sporting News Minor League Executive of the Year award, the first of three times he was selected. Dad, then with the Pirates as a batting instructor, must have been proud of his boys.

Cincinnati finished third in 1962 and fifth the following year. In late July 1964, as the Reds were battling the Giants and Phillies for the pennant, Sisler stepped in as manager for Hutchinson, who had terminal lung cancer. Over the next month Cincinnati gradually fell behind the Phillies, who built a six-game lead by the middle of September. The Reds then went on a 12-1 run as Philadelphia collapsed, reminiscent of their play in September of 1950. The Reds’ surge drove them into first on September 27, but they stumbled the last few days as the Cardinals eked out the pennant by one game over the Reds and Phillies.

A 10-0 loss on the last day to Philadelphia sealed Cincinnati’s fate. With a rapidly deteriorating Hutchinson in the clubhouse, Sisler said, “I’m only sorry we couldn’t have won it for that gentleman there.”41 Hutchinson had inspired all to play well despite his deteriorating health. Sisler, stepping into a difficult situation, drove the club to stay in the race.42

Two weeks later, after Hutchinson had formally resigned, club president Bill DeWitt named Sisler the manager. The announcement generated mixed emotions. Sisler was pleased, saying, “[M]anaging in the major leagues has always been my ambition,” and then acknowledged the ever-present comparison to his father: “I figure managing is the only way I’ll ever have a chance to beat any of my dad’s records.” Acknowledging that Hutchinson’s illness gave him his chance, he said, “I certainly hate to move up under these conditions.” Hutchinson for his part was happy for Sisler, telling DeWitt, “I’m happy to see you make Dick manager.”43 Within weeks Hutchinson was dead at the age of 45. Sisler’s selection as manager of the Reds gave him and his father the distinction of being the first father-son combination to manage in the majors.44

As the 1965 season began, Cincinnati was picked to finish third behind Philadelphia and the Cardinals.45 The Reds’ main strength was derived from a pitching staff considered one of the best in the league. Starters Jim Maloney and Jim O’Toole with Sammy Ellis and Billy McCool in the bullpen were the bedrock of the staff. Offense in 1964 was considered mediocre, with Frank Robinson the major threat.

Sisler tinkered with the lineup, placing Deron Johnson at third, allowing Gordy Coleman and Tony Perez to platoon at first. The shift paid dividends as Johnson led the majors in RBIs (130) with Coleman and Perez hitting a combined 26 home runs and driving in 104 runs, a major contribution to the Reds’ major-league-leading 825 runs scored.

But the pitching staff failed to deliver. Maloney and Ellis each hit the 20-win mark after Ellis was made a starter, but O’Toole and others fell off, the staff allowing 138 more runs than the year before. Still Cincinnati was just three games out going into the final week of the season before losing seven of their final eight to finish fourth.

The day after the season ended, DeWitt fired Sisler for “psychological reasons,” the last-week collapse probably influencing the GM.46 Those close to the club thought DeWitt often second-guessed Sisler’s handling of the pitching staff, effectively undermining Sisler. He was “bitterly disappointed” when told his contract would not be extended.47

Conjecture that DeWitt had wanted his own man, Don Heffner, the year before but gave way to Sisler as Hutchinson wished might have factored in.48 DeWitt’s firing of Sisler was questioned, but not as much as a trade he made later, sending Frank Robinson to the Orioles for Milt Pappas in what became widely considered one of the worst trades in baseball history. Heffner, hired to replace Sisler, lasted half the season. The team finished seventh.

Although Sisler had been offered a job in the Reds organization, he left and was quickly hired as a batting coach for St. Louis. He was with the Cardinals in 1967 and 1968 as they won pennants. In 1967 the Cardinals won their eighth world championship.

Sisler left St. Louis in 1970 to take on a full-time job as director of recreation for Tennessee’s Department of Corrections, at the invitation of Governor Buford Ellington. He supervised a staff of 30 who oversaw recreational activities for inmates at 10 facilities. In describing his position, Of his job, Sisler said, “A good recreation program affects a man mentally. There’s a lot of rehabilitation through recreation. It allows inmates to let out a lot of steam. It’s a chance for them to relax and get their minds off other things.” When asked if the job offered its rewards, he replied that helping an inmate do well after being released from prison gave satisfaction. “When we help someone, that’s pay in itself.”49

Sisler got back into baseball in 1976 when the San Diego Padres hired him as their batting coach. After two years with the Padres, he was again out of the game, but resurfaced in 1979 as batting coach with the New York Mets. His experiences and the lessons his father had shared with him over the years made him a sought-out instructor. After the 1980 season Sisler resigned from the Mets, and through the 1980s he was a roving instructor for the Cardinals, working with prospects in the lower minor leagues. After retiring from the game, he volunteered as batting coach at Belmont University in Nashville.50

Having hit one of the most dramatic home runs in baseball history, Sisler was always of interest to baseball writers who wanted to revisit the Whiz Kids’ 1950 pennant run. In 1988 and 1993 he shared his memories of his role in the team’s success with writers from the Philadelphia Daily News and Sports Collectors Digest, recalling how he hit with sore wrists against Don Newcombe.51

By 1994 Sisler’s memory began to fail and he went into a nursing home. Paul Rogers, who was working with Roberts on the Whiz Kids book, visited him. Rogers recalled that at 73, Sisler still looked as if he could still play. “He really stood out in contrast to the rest of the residents,” Rogers said. “It was very sad — he was in a spartan room with no hint of his baseball career. Just a bed, dresser, and chair and some family photos.”52 Sisler died on November 20, 1998, at the age of 78 after contracting pneumonia. He was survived by his wife, Dorothy; his son, Richard; three daughters, Kathleen Hand, Patricia Sweeney, and Shari Patterson; brothers Dave and George; his sister, Frances Drochelman; 10 grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.53

Rogers conducted many interviews for his book on the Whiz Kids and learned a lot about the team. Of Sisler, he said, “His teammates all loved Dick and told me he had a wonderful sense of humor. He was certainly one of the most popular guys on the team, perhaps the most popular. Just a genuinely likeable person.”54 For much of Sisler’s career he was compared unfavorably with his illustrious father, whether by teammates or writers. But none could ignore his reputation as a solid human being.

This biography appears in “The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies” (SABR, 2018), edited by C. Paul Rogers III and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

The writer would like to thank C. Paul Rogers III, co-author of The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant, for his comments and input on the text, and Mike Martin for use of his extensive baseball library.

Notes

1 Dick was the second of four children. George Jr., born in 1917, preceded him, Frances Eileen came along in 1922, and David in 1931. Rick Huhn, The Sizzler: George Sisler, Baseball’s Forgotten Giant (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2004), 65, 153.

2 Sisler’s record would last until 2004 when Ichiro Suzuki broke it with 262 hits. Baseball purists would note those 262 hits — five more than Sisler — were achieved in a schedule based on 162 games versus Sisler’s schedule, which called for 154 games.

3 Jim Barrero, “Out of Sight; Angels’ Erstad Made a Run at It, but for 80 Years, Few Have Threatened George Sisler’s Often-Ignored Record of 257 Hits in a Season,” Los Angeles Times, September 15, 2000: 1.

4 Huhn, 44, 274.

5 Barrero.

6 Huhn, 282.

7 Brent Kelley, “Dick Sisler: He Had the Biggest Hit in Phils’ History,” Sports Collectors Digest, February 22, 1993: 13D.

8 Huhn, 230.

9 Huhn, 277.

10 Ibid.

11 Stan Baumgartner, “Like Sisler, Like Son,” Sport, October 1950: 87.

12 Baumgartner, “Like Sisler, Like Son”; Richard Goldstein, “Dick Sisler, 78, Whose Homer Won ’50 Pennant for Phillies,” New York Times, November 23, 1998: 87.

13 “Dick Sisler Leaving Navy, to Join Cards,” unnamed, undated article in Sisler’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame; email from C. Paul Rogers III to author, dated December 3, 2016.

14 “People in Sports,” unnamed, undated article in Sisler’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

15 Sisler was approached by one of the Pasqual brothers trying to lure American ballplayers to an upgraded Mexican League. Among those who went south were Sal Maglie, Mickey Owen, and Vern Stephens. Sisler was offered $10,000 a year, then on declining was further lured with a car, a diamond wristwatch, and a pin. Sisler cut off negotiations by saying, “No. I couldn’t let my father down.” Baumgartner, “Like Sisler, Like Son”: 87.

16 Paul Pereira, “Ray Sanders,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/285e97e2.

17 Frederick G. Lieb, “Cards Super-Duper Rating Disturbs Dyer,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1946: 10.

18 “Cards’ Dick Sisler Bruised by a Hot One,” Atlanta Constitution, June 3, 1946: 16.

19 Sisler did not appear in either playoff game.

20 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 112-113.

21 Stan Baumgartner, “Sawyer Keeps Busy on Book of Phil’s Faults,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1948: 12.

22 Roberts and Rogers, 158-159.

23 Baumgartner, “Like Sisler, Like Son”: 44.

24 The rise of the Phillies in the late 1940s is covered in Roberts and Rogers, 28-64.

25 Baumgartner, “Like Sisler, Like Son”: 44.

26 Roberts and Rogers, 206.

27 After vying with each other for first base in 1949 and 1950, Sisler and Waitkus connected in a more positive manner in 1950 — they each enjoyed a skein of eight straight hits; Sisler accomplishing it on May 4-5; Waitkus in a doubleheader on August 27. Through 1992, it was the only time teammates accomplished this feat in the same year. Kelley.

28 Roberts and Rogers, 3, 269.

29 Baumgartner, “Like Sisler, Like Son.”

30 Sisler referring to his stutter as stammering lacked any sense of self-consciousness about his speech. Stories of his impediment, including those told by Sisler on himself, just enhanced his presence. In a game at the Polo Grounds, a popup was hit between first and second. Sisler attempted to call for the ball, “I gagaga” as the ball fell to the ground. He turned to second baseman Putsy Caballero and with a big smile on his face said, “You take it.” Roberts and Rogers, 113.

31 Roberts and Rogers, 273. Their account refers to a 3-2 loss at Wrigley Field. Per Retrosheet, however, the only home run Sauer hit off Roberts in 1950 came on September 19, at Shibe Park for a 1-0 Cubs victory.

32 Church was hit in the face by a line drive and missed a week and a half; Miller, with a sore arm, was ineffective most of September.

33 Huhn, 278. Another version of the elder Sisler’s reaction has him cheering and tossing his hat in the air, later telling reporters, “I’m a father first.” Ray Didinger, “Sisler Saves Whiz Kids,” Philadelphia Daily News, September 25, 1988: G-33. When recounting his reaction to his son’s home run, the elder Sisler said, “I have three sons and when each was 10, Dick looked like the worst ballplayer of the lot. I hoped one of my sons would follow in my footsteps, but I never thought it would be Dick.” “Felt Awful and Terrific at Same Time,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1950: 5.

34 There is a backstory to Sisler’s home run. That morning he rode to the game in a cab with several teammates. They stopped at a red light and another cab pulled alongside. A man and his three sons had come up from Philadelphia to watch the game. When he recognized the players, he told the cab driver to stop. He gave a red rose in a glass to Sisler, telling him, “I went to church this morning and I took this flower off the altar. I want you to have it. Put it on top of your locker.” Sisler thanked him. Maje McDonnell, a Phillies coach who was in the cab with Sisler, later recalled, “After the game was over and I ran into the clubhouse, I saw the flower above Dick Sisler’s locker. And he is the one who hit the home run. Isn’t that amazing?” Roberts and Rogers, 321, 334. Sisler shared a slightly different version of the story that involved a priest giving him the rose which, was included in the obituary by Richard Goldstein cited in Note 12.

35 Sandy Padwe, “When Dick Sisler Won Literary Immortality,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 24, 1968.

36 African Americans did not appear in a major-league game for Philadelphia until 1957, one decade after Jackie Robinson’s debut.

37 Bob Broeg, “Rebuild With Youth, Stanky’s Long-Term Card Assignment,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1953: 4; “Deals of the Week, Majors-Minors,” The Sporting News, August 12, 1953: 34.

38 Sisler played for Columbus, San Diego, and Nashville between 1953 and 1958, hitting over .300 four times, including a .332 mark in 1957, seventh in the Southern Association. His last active season was with Nashville in 1958 when he hit .283 part-time as a player-manager. Sisler began managing Nashville in 1957 and compiled a .535 winning percentage for the three seasons he managed there. In 1960 the Seattle Rainiers finished at 77-75, in fourth place, with Sisler at the helm.

39 Doug Skipper, “Wally Moses,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/4be0756d.

40 Pat Harmon, “Sisler’s Rare Skill: Dick Gets Message Across to Player,” Cincinnati Post, August 10, 1964; Clifford Kachline, “Losing Reds Almost Equaled Winning Cut of ’40 Rhineland Club,” The Sporting News, October 25, 1961: 4. That season also marked Jim Brosnan’s second literary effort, Pennant Race, in which he chronicles the Reds’ experiences on and off the field. Brosnan writes of ribbing Sisler to have the team score more runs, to which Sisler retorted, “I’ll do that, Hemingway. And you put it in your book.” Jim Brosnan, Pennant Race (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1962), 135. Brosnan’s first book, The Long Season, covered the 1959 season.

41 Clay Eals, “Fred Hutchinson,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/8584a2d4.

42 The team finished with a .568 winning percentage; Sisler had coaxed the team to a 32-21 record in the 53 games he managed, a .604 pace. Under Hutchinson the Reds were 60-49, a .550 winning percentage.

43 Earl Lawson, “At Last Sisler Has Chance to Overshadow Dad,” Cincinnati Post, October 31, 1964.

44 A legitimate argument can be made that Connie Mack and his son Earle comprised the first father-son managing combination, but the younger Mack was merely filling in for his father on a temporary basis due to illness. Dick Sisler was signed to a contract to manage for the 1965 season.

45 Clifford Kachline, ed., Official Baseball Guide for 1966 (St. Louis: Charles C. Spink & Son, 1966), 12, 23.

46 Ryne Duren and Jim O’Toole related several incidents of rowdiness and lack of effort in the 1964 pennant race, suggesting the team had gotten away from Sisler, and this perhaps influenced DeWitt a year later. See Danny Peary, ed., We Played the Game: 65 Players Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era, 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994), 605-606.

47 Earl Lawson, “Sisler Managed, but DeWitt Called the Shots,” Cincinnati Post, October 5, 1965.

48 Lawson.

49 Associated Press, “Recreation Aids Rehabilitation,” February 1, 1973; United Press International, “Sisler Helps Convicts,” undated. Both articles are found in Sisler’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

50 Email from Peter Drochelman, Sisler’s nephew, December 9, 2016.

51 Didinger; Kelley.

52 C. Paul Rogers, email to author, November 29, 2016.

53 Goldstein.

54 Rogers, email to author, November 29, 2016.

Full Name

Richard Allan Sisler

Born

November 2, 1920 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

November 20, 1998 at Nashville, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.